Полная версия:

Short Life in a Strange World: Birth to Death in 42 Panels

On the wall opposite the Census, there is a large canvas, an Adoration of the Magi. This is not generally attributed to Bruegel, but may be after a lost composition, like the Icarus. It is in watercolour, an unusual medium for Bruegel. There is a tempera Blind Leading the Blind in Naples, and a Misanthrope; there is The Wine of St Martin’s Day in Madrid; otherwise it is all oil, all panel.

The canvas is badly damaged. Who knows how many panels have been lost over the years, painted over, chucked in skips, on bonfires. Van Mander mentions two versions of Christ Carrying the Cross (one remains); a Temptation of Christ, with Christ looking down over a wide landscape; a peasant wedding, in watercolour, with peasants giving presents to the bride; and one other watercolour in the hands of the same collector, undescribed. We know of others, gone missing. A crucifixion. A miniature Tower of Babel. The first in the sequence of The Months (April/May).

Whatever Bruegel saw when he contemplated his own Bruegel Object is lost to us, a ghost configuration. Whatever might be vouchsafed to posterity from a life lived – in Bruegel’s case, a lot; in my case, as in most cases, nothing – is only very approximately indexed to that life. I have very little interest in biography. It is not Bruegel’s completeness that I am interested in but my own. But I am conscious that the dead panels stand whispering beyond my spreadsheeted ring of firelight, and no amount of conjuring will induce them to step forward. It is too late.

When my father died in 2009, he was eighty-four years old. A double-Bruegel. The parallelisms proliferate. I consciously peg each year in my life, for example, to a year in my father’s, according to the age of our children: so in 2017, when my Bruegel project finished, my children were nine and eleven; my brother and I were nine and eleven in 1978.

Robert Henry Ferris in 1978 was making his last throw of the dice, leaving GEC, the General Electric Company – the huge conglomerate where he had worked, barring an interruption for war service, for nearly forty years – for a much smaller company, where he might just hope to be a bit of a big fish. That didn’t really work out either. He was fifty-three, and his heart wasn’t in it. He told me after he retired that, in all the years of his working life, he had never been early for work once. He had a lively mind and a fairly dull job. He didn’t travel much. He just sort of stopped.

One evening, at around that time, he sat down and wrote in an enormous year diary one line: It is said that in every life there is one story. This is mine.

One line a night was enough, he said. If you wrote one line a night you would soon have a great big book. I was nine, and I was impressed. But it was too late. He liked his sedentary whisky too much, could never find the energy to add anything to that one line. He could certainly write, but he lacked technique and discipline. And there it stayed on a shelf, the weighty volume with the solitary line and several hundred enormous blank pages, like the blank cells of my spreadsheet. A metaphor, and a bit of a shitty one at that. From time to time my brother or I would take down the volume and study it, either to shame him publicly (and he would laugh along jovially enough at his own foolishness) or to teeter privately on the brink of some immense intuition: not only was our father’s life unfulfilled, but all life was most likely unfulfillable. ‘It is this deep blankness is the real thing strange,’ writes the poet William Empson. And there it was, this deep blankness, sitting on a shelf in our living room.

My father went on in due course to his deeper blankness, his long home. But when he was in hospital dying, my brother was searching the census records of our paternal family. My father was always reticent with family history. He had been born in 1925 in Camden, had grown up there and on Portpool Lane off the Gray’s Inn Road, and later in Lee Green. There were some disconnected anecdotes – a story about a broken radio, about a Jewish funeral, about an aunt who sprinkled sugar on his buttered bread – not much else.

His mother had died of heart disease during the war when he was a very young man. He rarely spoke about her, but on one memorable evening over whisky towards the end of his life he found he could not recall her name. The grip of my father’s memory was utterly secure until his last day. But he could not remember his mother’s name.

Later, he dredged it up from somewhere. Anne. My brother uncovered more detail, and relayed it to my father in hospital. She was recorded as Annie on the census of 1911, at nine years old the youngest of five sisters growing up on what is now Tavistock Street, just off Drury Lane. She had been born around the corner on Stanhope Street, coloured black on Charles Booth’s poverty map of the late 1880s to designate ‘Lowest Class. Vicious, semi-criminal’. Stanhope Street along with the whole rookery around Clare Market was bulldozed soon after to make way for the arterial Kingsway. No. 1 Kingsway would become, until 1963, the head office of GEC, my father’s first place of work. In 1940, during the Blitz, he would firewatch from its roof, and could have lobbed a cricket ball through the vanished window of his mother’s slum birthplace.

Years later my grandfather told my mother that his wife – Annie – had had a temper on her. Choleric. Hot blood. Hasty heart. The death of her. She died, as I say, of heart disease in 1944, aged forty-two. Years of Bruegel. My father travelled down from Scotland where he was based with Coastal Command, whether in the nick of time, to watch by her bedside as the candles flickered out, or too late, I do not know. He was an only child. He and his father were thrust together to deal with this small loss in a world undergoing incalculable loss.

My father was not obviously close to his father. Pop, as he called him, lived with us until he died when I was eight. My mother says my father rarely addressed him, never had a conversation with him. Who knows if it was trauma, or sadness, or indifference which sundered or secretly united them.

When Pop died, only my father and my mother attended his funeral. My father took Pop’s remaining possessions – a few books, razor, alarm clock, wallet and clothes – and put them in a bin bag and slung them on the municipal dump. There was to be no gravestone, no memorial rose, no bench in a park, nothing to visit.

But within the year my father sat down at the empty diary and confronted its alarming blankness.

In truth, all this biographical detail was probably less use to my father than his anecdotes, and in any case it was difficult to gauge his response – his circuit of interest had contracted to the point where all that concerned him were the minutiae of the routines that were eking out his life.

But for my brother and me it assuaged the sense that here was a disconnected dot, about whom we knew not very much, going into the darkness. There was a chain. He was linked, and so were we. It was written in the census.

People may be numberless, but they are not identical; you are defined both by your similarity to and by your discrepancy from them. So, spot the difference.

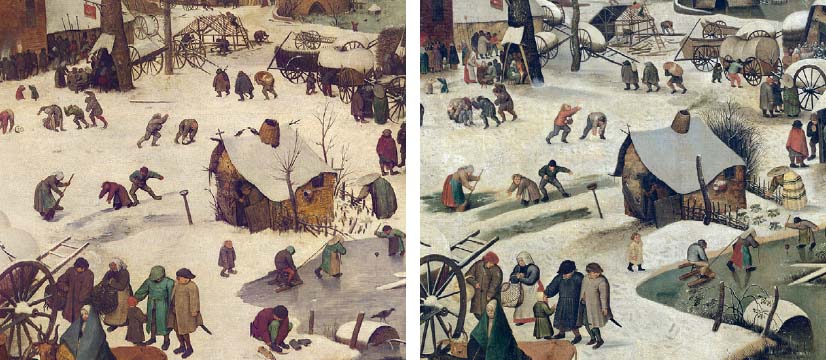

The Younger’s panel is fractionally larger – he may have been working to Antwerp rather than Brussels feet. Whatever the reason, the result is that figure groups, for which there would have been separate cartoons, are pulled this way and that within certain tolerances, marginal plays.

No two figures are dressed alike, fabrics change colour, there are odd reversals. The woman in the lower right, for example, wears a red-green combination of overskirt and underskirt inverted in the Brueghel copy. There are microscopical differences between faces, individual posture. The Younger had his own way with trees, bushy rather than twiggy.

Criss-cross tracks, paths, desire lines: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Younger (left) and Elder (right).

And then, more slowly, I see that the Younger favours tracks. From the bottom right, where Mary has entered on her donkey or ass, to the top left across the frozen river; and again, from the wheels of the foreground frozen carts, there are criss-cross tracks, paths, desire lines, animating the space. This is a frozen world, but there is evidence of networks, organized around an axis.

The Elder’s foreground carts, by contrast, are going nowhere. There are no paths, just yellowish ice wallows. He has painted a village of spindly cartwheels, a spindly ladder against a spindly barn, spindly trees. And he has painted a world of endlessly repeated circles – the wreath, the barrels, and especially the cartwheels, thirty-one of them, including one a fraction below dead centre, hitched to no wagon and orthogonal to the viewer, as though it were not a material object at all, but a diagram of the interlocking cycles of village life and the seasons, of the great wheels of history and Christian redemption.

Hitched to no wagon: The Census at Bethlehem, detail.

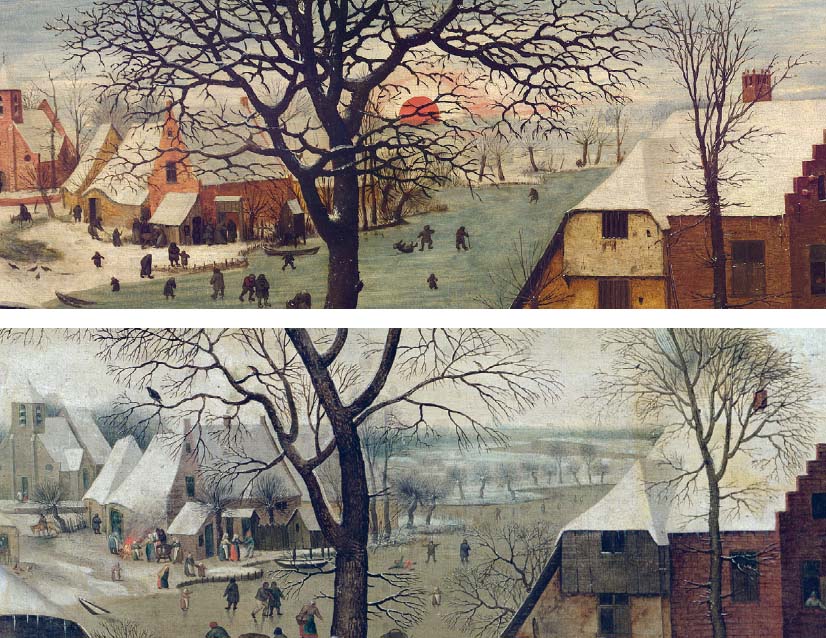

And then finally I recognize what sets the two paintings apart: the Younger, perhaps seduced by those few inches in hand, has raised the branches of the largest foreground tree a fraction to reveal what in the Elder there is none of – a vanishing point, or what the Italians call a punto di fuga, a fugitive point, a point of escape. The Younger’s brown frozen river winds out of the panel. His father’s, by contrast, is entangled in the branches, perhaps coils around the back of the village, a labyrinthine waterway.

The only thing vanishing is that peculiar sun. The old world is ebbing to its conclusion.

The Younger – wittingly? unwittingly? – has made this dead cosmic circuitry bearable, transient. Along those paths and on that frozen river our eye is made to criss-cross, not circle, and finally escape the painting. And he has done all this in direct contravention of the central thought process of the original – that these circles go nowhere for a reason.

A vanishing point: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Elder (top) and Younger (bottom)

Pieter Brueghel the Younger may not have been a painter at all. He was unarguably an eminent man in the Antwerp art world – there is a portrait etching of him by Anthony van Dyck, in which, as it happens, he projects the sort of patient melancholy common to men with drooping noses and straggling moustaches. But he may only have been the inheritor of the cartoons and the general manager of a workshop which employed anonymous hands to complete the copies. It is possible that he had no artistic personality, nothing but a signature and a locked chest of cartoons which he carefully opened and closed as required, a bureaucrat among artists, ghosting through the system, the painted artefacts. The notion that somewhere in that swirl of hands and methods and corporate production was the memory of a five-year-old boy transfixed by the death of his father is nothing more than an absurd projection of my own.

But this is why I am here. I did not come into this room in Brussels to discover a truth, but to impose one. To make something of all this. This is one way in which we react to the accumulation of life. We make spreadsheets, trace genealogies, embark on projects, write essays. We pore over the data in search of patterns. All this must and will be made to mean something.

I stand in the corner room of the museum, then, observing small differences. Discriminating.

And there is in fact one final difference – a figure, present in the Elder’s panel but absent in all the Younger’s copies, suggesting a late emendation on the father’s part, a final gratuitous flourish of his art: it is the youth pulling on his skates, below the tiny child who cannot yet summon the courage to go out on the ice.

Life is treacherous, says the figure, but we have resources. We have skates. We can make of this treacherous ice our element. Sooner or later, we all pull on our skates and go out on the ice – as the father might have remarked to the son, had he had time.

We have resources: The Census at Bethlehem, detail – Elder (left) and Younger (right).

This whole village, in fact, suddenly seems to be poised by the ice, spilling uncertainly but inevitably over its edges. Just to the right of the large tree by the water a father stands hands in pockets and watches his two small children testing the curious element.

The skater’s absence from all copies (bar one – a recently discovered panel has the skater, suggesting a late, rectifying glimpse of the original, or a post-mortem addition) implies that it was the father who was diverging, making changes on the hoof, inserting figures at the last minute, blotting out the vanishing point in a moment of inspiration, and the son who adhered more faithfully to the earlier version, the cartoon or, more likely, sheaf of cartoons. There is, after all, a sensibility in copying well, an alertness to detail. One of the Younger’s guiding virtues, you could say, was fidelity. Copying is meditative and respectful work, itself a way of thinking.

If he was occasionally caught out by the odd detail it hardly matters. At some point the fractional differences collapse into the far greater mass of similarities. The census is not a record of our individuality in the end, but of our solidarity. Thus there is not a source of pictorial DNA – the Elder – and a series of ever-degrading replications. Rather there are versions of versions all orbiting a hypothetical centre of mass (the cartoon), just as the small children of the village eccentrically orbit the centres of mass set up between them and their parents, and their parents in turn orbit the invisible barycentre which lies between them and their ancestors, and which we commonly call the community. Each of us, present or absent, exerts our own small constant gravitational tug, variable in time, hard to calculate, take account of; but there, nevertheless, in the mass of data points, and the geometry which comprehends it.

III Fire

Antwerp and Rotterdam (6.316%)

‘The air still moves, and by its moving cleareth, The fire up ascends, and planets feedeth.’

Fulke Greville, Caelica

Months pass, and I wage a phoney war against the looming Bruegel Object, pick off a panel here or there, drag myself like a forlorn expedition over the still-featureless map of all Bruegel. Finding landmarks.

The cities I visit are cities named in a dream of Europe. Rotterdam. Antwerp. Places you might struggle to put a pin in, but which underlie your notion of European. Once I have visited them, I hardly know that I have been there: waystages on a cosmic map.

Rotterdam, for instance. Rotterdam is a station, roadworks, new buildings, a long straight walk to the museum along a windy street. It is a museum built in the 1970s, an empty café with coloured chairs.

That is Rotterdam. Have I been there? Barely.

*

I am in Rotterdam with a friend, a painter called Anna Keen. Sister of Zabdi, my paragliding instructor. In Rome in the 1990s we were a couple. We lived behind the Colosseum on top of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s cavernous, mouldy, buried golden palace, with its revolving dining room and its obscene frescos.

Now Anna lives in Amsterdam, in a shed near the water, and I am paying a visit. In a couple of days my brother will join us.

The shed is part of a complex of work units – next door, for example, is a builder of speedboats, or racing yachts, I do not remember which. I only remember looking down the length of streamlined hulls, bright paintwork, varnish. Rigging? I don’t recall.

Anna’s shed is also her home and a source of income – she sublets parts of it as studio and living space to art students. Her brother Nick, a carpenter, has come over for a few days and built partition walls. Anna lives upstairs in the low-ceilinged loft that runs the length of the shed. You have to stoop as you walk along it. You ascend by a ladder between two antique electrostatic speakers into her wonky space of two thousand books and paint-stained electronics – laptop, router, amplifier, speakers – and naked plasterboard. A padded silver pipe runs up through the floor. Plastic flapping windows give on to the main space, where Anna has her own wooden boat propped up and her immense easel, and endless red-and-white packets of a line of budget food called Euro Shopper which for some reason she cannot stop buying, and presumably consuming, and wants to paint. On each packet is a schematic drawing indicating the packet’s contents – a red-and-white cow (milk), a red-and-white peanut (peanut butter), a red-and-white gravy boat (brown sauce), a red-and-white whisk (whipping cream, UHT). They are everywhere. A ready-made Warholian homogenization of all food and all household goods, in this most dehomogenized of spaces.

Anna has installed a large wood-burning stove in her kitchen, and it directs heat around the shed complex along silver-insulated pipes. It is February, the stove is working full time, and everything you touch is either scalding hot or icy. The inhabitants of the shed (three, four art students, Anna, Anna’s brother, Anna’s brother’s girlfriend, my brother, and me) shuffle around wrapped in scarfs and old jumpers, clutching mugs of tea, seeing how close we can get to the fiery stove without singeing our flesh. Whatever the stove radiates seems to dissipate within an inch or two of its cast iron: the zone of warmth is perilous and narrow.

I persuade Anna to come to Rotterdam and look at the Bruegel.

Rotterdam. To recapitulate: a station, a street, a museum, the wind, and The Tower of Babel.

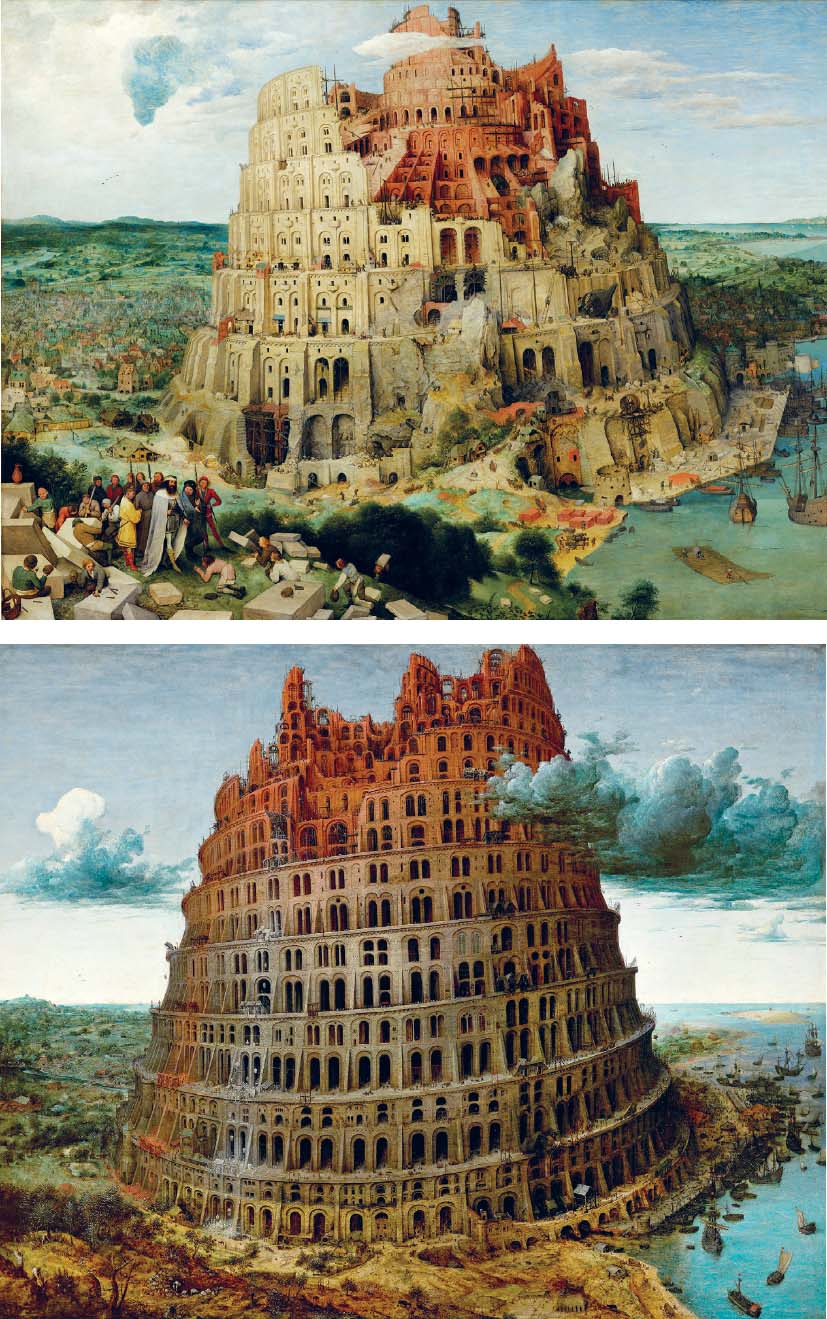

Museums are for the most part horizontal structures. I do not know many properly vertical museums. But the Rotterdam museum contains one of the great essays in verticality. It is the smaller of Bruegel’s two Babel panels – the other hangs in Vienna – but the larger of the two towers. The compositions are similar. The Vienna tower is built around a cankerous rock and in the foreground, receiving obeisance from his stonemasons, there is a king (Flavius Josephus ascribed the building of the tower to Nimrod); the ships are much larger than those in the Rotterdam panel, the horizon subtly higher; in Rotterdam we are higher, therefore, and see further.

Essays in verticality: The Tower of Babel – Vienna (top) and Rotterdam (bottom).

The rocky outcrop jutting from the Vienna tower is not the foundation but the metamorphosis of the built structure – there can have been no pre-existing plugs of rock on this flat plain. The weight of the tower has compressed and transformed its materials. It is subsiding on the shore side into marshy land.

The Rotterdam panel, on the other hand, is a pure geometry. Lessons have been learned. The only transmutation of materials here is into upthrusting energies. No wonder the builders’ jealous god got worried.

Both towers not only dominate their respective landscapes: they are the landscape. Everything of interest on the nondescript plains is subsumed into the towers, just as a great city – Antwerp, for instance, or Brussels – will suck economic energy from the land and the seas which surround it.

Bruegel was an inheritor of the Netherlandish tradition of the World Landscape – painters such as Herri met de Bles and Joachim Patinir had for a generation before Bruegel produced increasingly broad and schematic landscapes where great rivers and mountains and plunging precipitate views and cliffs and oceans beyond stood as much for a representation of the cosmos as for anything you might see in nature.

Landscape started to emerge from the background, took a sociological, topological, cartographical, thematic turn. It became not just a reflection of cosmic order but the whole theatre of man and his salvation, the teatrum mundi, the theatre of the world.

Bruegel introduced a note of difference, however. A naturalism. Simon Schama observes that, relative to the work of Patinir and met de Bles, the landscapes of the early seventeenth century had been ‘deprogrammed’. They had ceased to be grand schematics of the cosmos, or moral topographies, and were now ‘just’ trees, woods, streams. And this process of deprogramming begins with Bruegel.

In around 1552, Bruegel, a young painter newly emerged from his apprenticeship, travelled to Italy, most likely with fellow painter Maarten de Vos and the sculptor Jacob Jonghelinck. He travelled down through France (we know of a lost gouache View of Lyon); proceeded over the Alps to Rome, where he stayed for two years; and then pressed on more briefly to Naples, Reggio Calabria, and in all likelihood Sicily.

Such a trip was not unusual for ambitious Northern painters, who were expected to educate themselves in the ruins of classical antiquity and the works of the Italian Renaissance masters. Bruegel most likely did precisely that but, perhaps at the instigation of the Antwerp printer Hieronymus Cock, he also documented his trip with reams of topological views: the Bay of Naples, Reggio Calabria, the Strait of Messina, Rome, the Alps. And on his return, it was with these views and a set of generic engravings – the so-called Large Landscapes, incorporating elements of his Alpine journey – that the young Bruegel established his reputation. ‘On his travels,’ wrote Van Mander, ‘he drew many views from life so that it is said that when he was in the Alps he swallowed all those mountains and rocks which, upon returning home, he spat out again on to canvases and panels.’

Bruegel had a precise eye. His work has been described as ‘ethnographic’, so fastidious is it with details of peasant life, and in the same way his World Landscapes never neglect shape of leaf or jizz of flying bird – a generic silhouette in the sky is, on closer inspection, a magpie or a cormorant; a foreground plant is not just an iris but an Iris germanica. The natural world adorns the schematic landscape, or the schematic landscape polarizes the naturalistic detail, in a way that Ruisdael or Hobbema, or Constable or Monet, would have understood. The real keeps impinging on the meaningfully arranged. And vice versa. We are caught in suspension between what God ordains and what Bruegel experiences. And the two are not necessarily aligned.

On his Italian journey, Bruegel must have seen and drawn, and, to judge from his versions of Babel, slightly obsessed over, the Colosseum. Both the Rotterdam tower and the Vienna tower are colosseums telescoping upward to infinity. Both are set on the plain. There are some distant hills in the Vienna panel, none in the Rotterdam panel. To repeat, both towers are the landscape, translations of the cosmic landscape into urban form. These are stone cities pulled up from the earth in the manner of origami trees, birthing strange rocks, over-topping the clouds, bending the frame of the earth. Symbolic, but also detailed. Naturalistic.

The Rotterdam tower – the later of the two, by some five years – is both an architectural and a chromatic fantasy.

At the top, the endless intricacy of its internal form is revealed. The Gothic variation and repetition of its windows and arches makes of them not merely entrances but a sort of hyperbolic internal structure, as though the builders had lighted on some multidimensional or geodesic solution to the incalculable stone weight of the structure that had defeated them in the Vienna panel; this fresh tower will go up and up supporting its own weight on tensile Gothic arches and windows.