Полная версия:

The Complete Legends of the Riftwar Trilogy: Honoured Enemy, Murder in Lamut, Jimmy the Hand

RAYMOND E. FEIST

The Complete Legends of the Riftwar

Trilogy

Honoured Enemy Murder in LaMut Jimmy the Hand

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

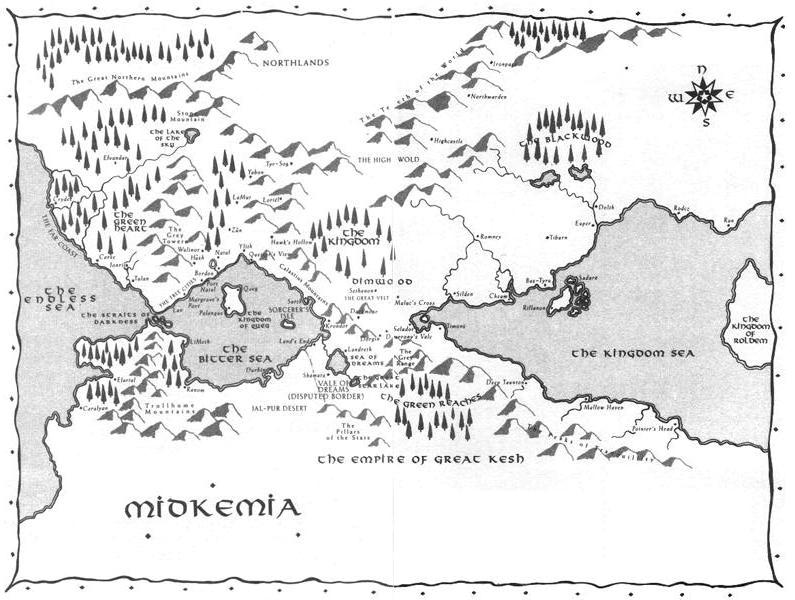

Map

Honoured Enemy

Murder in LaMut

Jimmy The Hand

Continue The Adventure …

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Map

RAYMOND E. FEIST & WILLIAM R. FORSTCHEN

Honoured Enemy

Book Two of Legends of the Riftwar

This one’s for Janny Wurts, who showed me that two heads often were far better than one.

Raymond E Feist

When I think of Honour, Colonel Donald V Bennett, Fox-Green, Omaha Beach, and Sergeant Andy Andrew, Easy Red, Omaha Beach stand before me. When duty called, they served unflinchingly. I am honoured to call them my friends.

William R Forstchen

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

Prologue: Intelligence

Chapter One: Grieving

Chapter Two: Discovery

Chapter Three: Moredhel

Chapter Four: Practicalities

Chapter Five: Accommodation

Chapter Six: Pursuit

Chapter Seven: River

Chapter Eight: Decisions

Chapter Nine: Chances

Chapter Ten: Valley

Chapter Eleven: Respite

Chapter Twelve: Blood Debts

Chapter Thirteen: Accord

Chapter Fourteen: Betrayal

Chapter Fifteen: Flight

Chapter Sixteen: Confrontation

Chapter Seventeen: Parting

Epilogue: Reunion

Acknowledgements

Copyright

• Prologue •

Intelligence

THE RAIN HAD STOPPED.

Lord Brucal, Knight-Marshal of the Armies of the West, entered the command pavilion, snorting like a warhorse and swearing under his breath. ‘Damn weather,’ he finally said. The elderly general, still broad-shouldered and fit, ran a gloved hand back from his forehead, getting the damp hair out of his eyes.

Borric, Duke of Crydee, and his second-in-command looked at his old friend with a wry smile. Brucal was a steadfast warrior and a reliable ally in the politics of the Kingdom of the Isles, as well as an able field general. But he had a tendency towards vanity, though. Borric knew he was getting irritated by the regal mane of hair now being plastered to his skull.

‘Still sick?’ Borric was a striking man of middle years, with more black in his hair and beard than grey. He had on his usual garments of black – the only colour he had donned since the death of his wife many years before – and over this he wore the brown tabard of Crydee, emblazoned with a golden gull above which perched a small golden crown, signifying Borric’s royal blood. His eyes were dark and piercing, and currently showed a slight amusement at his old friend’s bluster.

As Borric expected, the old grey-bearded duke swore an oath. ‘I’m not sick, damn it! Just a bit of a sniffle.’

Borric remembered Brucal when he was a young man, visiting Borric’s father at Crydee, his laughter, with his robust joy and a glint in his eye. Even when his reddish-brown hair and beard had turned grey, Brucal had been a man who lived each day to the fullest. Today was the first time Borric recognized that Brucal was now an old man.

On the other hand, it had to be said that Brucal was an old man who could quickly draw a sword and do considerable harm. And he refused to admit he was ill.

Brucal pulled off his heavy gauntlets and handed them to an aide. He allowed another to remove the heavy fur-lined weather-cloak he had worn from his own tent. He was dressed in simple blue trousers and a grey tunic, his tabard left behind in his tent. ‘And this bloody rain doesn’t help.’

‘Another week of this and the snows will be falling in earnest.’

‘According to our scouts, it’s already snowing heavily up north, around the Lake of the Sky,’ replied Brucal. ‘We should consider sending the reserves back to LaMut and Yabon for the winter.’

Borric nodded. ‘We might get one more week of clement weather before the winter storms come, though. Just enough time for the Tsurani to start something. I think we’ll keep half of the reserves close by; I’ll order the other half back to LaMut.’

Brucal looked at the campaign map on the large table before Borric. He said, ‘They haven’t been doing much, lately, have they?’

‘The same as last year,’ said Borric, pointing at the map. ‘A sortie here, a raid there, but there’s little evidence they seek to expand much any more.’

Borric studied the map: the invading Tsurani had taken a large chunk of the Grey Tower Mountains and the Free Cities of Natal, but had seemed satisfied to hold a stable front for the last five years of the war. The dukes had managed one successful raid through the valley in the mountains the Tsurani had used as their beachhead, and since then intelligence about what was occurring behind enemy lines was non-existent.

Brucal blew his nose in a rag used to oil weapons, and then threw it into a brazier nearby. His large nose now looked red and shiny. The nine-year campaign had taken its toll on him, Borric noticed.

Borric thought back a moment to when the first sightings of the Tsurani invaders had been reported, by two boys at his own keep who had found a wrecked Tsurani ship on the headlands near his castle at Crydee. Later, word had been brought by the Elven Queen of aliens in the forests that lay between her own Elvandar and the Duchy of Crydee.

The world had changed: the fact of an alien invasion from another world via a magic gate was no longer a source of wonder. Borric had a war to fight and win. He had added some marks with brush and ink to the campaign map.

‘What’s this?’ asked Brucal, pointing to a notation Borric had added earlier in the morning.

‘Another migration of Dark Brothers. It looks as if a fairly large contingent of them are moving down the southern foothills of the Great Northern Mountains. They’re treading a narrow path near the elven forests. I can’t understand why they’d come over the mountains at this time of year.’

‘Those blackhearts don’t have to have a reason,’ observed Brucal.

Borric nodded. ‘My son Arutha reported a large force tangled with the Tsurani while they were besieging my castle five years ago. But those were Dark Brothers driven from the Grey Towers by the Tsurani; they were striking north to join their kin in the Northlands. They’ve been quiet since then.’

‘There’s one possibility.’

Borric shrugged. ‘I’m listening, old friend.’

‘That’s a bloody long trek for nothing,’ observed Brucal, as he wiped his nose with the back of his hand. ‘They’re not fools.’

‘The Dark Brotherhood is many things, but never stupid,’ agreed Borric. ‘If they’re moving in force, it’s for a reason.’

‘Where are they now?’

Borric said, ‘Last reports from the scouts near the Elven Forest. They’re avoiding the dwarves at Stone Mountain and the elven patrols, heading east.’

‘Lake of the Sky is the only destination,’ said Brucal, ‘unless they’re going to turn south and attack the elves or the Tsurani.’

‘Why Lake of the Sky?’

‘It makes sense if they’re trying to get up to the eastern side of the Northlands. There’s a spur of mountains that runs north-east out of the Teeth of the World, hundreds of miles long and impassable. Over the Great Northerns, past the Lake of the Sky, and up a trail back north over the Teeth of the World is a short-cut, actually.’ The old duke stroked his still-wet beard. ‘It’s one of the reasons we have so much trouble with the bastards up in Yabon.’

Borric nodded. ‘They tend to leave us alone in Crydee, compared to the encounters your garrisons have with them.’

‘I just wish I knew why they were out in force, heading east, this close to winter,’ muttered Brucal.

‘Something’s up,’ said Borric.

Brucal nodded. ‘I’ve been fighting Clan Raven since I was a boy.’ He fell silent for a moment. ‘Their paramount chieftain is a murderous dog named Murad. If this bunch from the Northlands is looking to join with him …’

‘What?’

‘I don’t know, but it’ll be bad.’ Looking over the rest of the map, Brucal asked, ‘Do we have anyone in that area now?’

‘Just the garrison forts along the Tsurani front, and a few last patrols before winter,’ Borric replied.

Brucal leaned close to inspect each of the small ink marks on the map, then made a sound half-way between a snort and a laugh. ‘Hartraft.’

‘Who?’ asked Borric.

‘Son of one of my squires. Dennis Hartraft. Runs a company of thugs and cut-throats called the Marauders for Baron Moyet. He’s up there.’

‘What’s he doing?’ asked Borric. ‘The name is familiar, but I don’t recall any reports from him.’

‘Dennis is not one for paperwork,’ said Brucal. ‘What he’s doing is unleashing bloody murder on the Tsurani. It’s personal with him.’

‘Can we get word to him about this Dark Brothers migration?’

‘He’s an independent. He’ll come back to Moyet’s camp for the winter in the next week or two. I’ll send word to the Baron to get whatever information from Dennis he can.’ Then Brucal laughed. ‘Though it would be fitting for him and Clan Raven to tangle if it comes to that.’

‘Why?’

Brucal said, ‘Too long a story to tell now. Just say there’s even more history between his family and Murad’s blood-drinkers than there is between him and the Tsurani.’

‘So what happens if this Hartraft and the Dark Brothers meet up?’

Brucal sighed, and wiped his nose. ‘A lot of people are going to get dead.’

Borric took a step away from the map table and looked out of the pavilion’s door. A light mix of rain and snow was starting to fall. After a moment, he said, ‘Maybe they’ll miss each other and Hartraft will get back to Moyet’s camp.’

‘Maybe,’ said Brucal. ‘But if that bunch from the north gets between Dennis and Moyet’s camp, or some bunch from Clan Raven moves to meet with them …’

Brucal let the thought go unfinished. Borric knew what he thought. If that many Brothers got between Hartraft and his base, the chances for the Kingdom soldiers returning home alive were nearly non-existent. Borric let his mind wander for a moment, considering the cold hills of the north and the icy winter almost upon them, then he brushed away the thoughts. There were other fronts and other conflicts to worry about, and he couldn’t help Hartraft and his men, even if he knew where they were. Too many men had already died in this war for him to lose sleep about another high-risk unit out behind enemy lines. Besides, maybe they’d get lucky.

• Chapter One •

Grieving

THE GROUND WAS FROZEN.

Captain Dennis Hartraft, commander of the Marauders, was silent, staring at the shallow grave hacked into the frozen earth. The winter had arrived fast and hard, and earlier than usual; and after six days of light snow and freezing temperatures, the ground was now yielding only with a grudge.

So damned cold, he thought. It was bad enough you couldn’t give the men a proper funeral pyre here, lest the smoke betray their position to the Tsurani, but being stuck behind enemy lines meant the dead couldn’t even be taken back to the garrison for cremation. Just a hole in the ground to keep the wolves from eating them. Is this all there really is in the end, just the darkness and the icy embrace of the grave? With his left hand – his sword hand – he absently rubbed his right shoulder. The old wound always seemed to ache the most when snow lay on the ground.

A priest of Sung, mumbling a prayer, walked around the perimeter of the grave, making a sign of blessing. Dennis stood rigid, watching as some of the men also made signs to a different god – mostly to Tith-Onaka, God of War – while others remained motionless. A few looked towards him, saw his eyes, then turned away.

The men could sense his swallowed rage … and his emptiness.

The priest fell silent, head lowered, hands moving furtively, placing a ward upon the grave. The Goddess of Purity would protect the dead from defilement. Dennis shifted uncomfortably, looking up at the darkening clouds which formed an impenetrable wall of grey to the west. Over in the east, the sky darkened.

Night was coming on, and with it the promise of more snow, the first big storm of the year. Having lived in the region for years, Dennis knew that a long, hard winter was fast upon them, and his mission had to be to get his men safely back to their base at Baron Moyet’s camp. And if enough snow fell in the next few days, that could prove problematic.

The priest stepped back from the grave, raised his hands to the dark heavens and started to chant again.

‘The service is ended,’ Dennis said. He didn’t raise his voice, but his anger cut through the frigid air like a knife.

The priest looked up, startled. Dennis ignored him, and turned to face the men gathered behind him. ‘You’ve got one minute to say farewell.’

Someone came up to Dennis’s side and cleared his throat. Without even looking, Dennis knew it was Gregory of Natal. And he understood his lack of civility to the Priest of Sung was ill-advised.

‘We’re still behind enemy lines, Father. We move out as soon as the scout comes back,’ Dennis heard Gregory say to the priest. ‘Winter comes fast and we’d best be safely at Brendan’s Stockade should a blizzard strike.’

Dennis looked over his shoulder at Gregory, the towering, dark-skinned Natalese Ranger attached to his command.

Gregory returned his gaze, the flicker of a smile in his eyes. As always, it annoyed Dennis that the Ranger unfailingly seemed to know what he was thinking and feeling. He turned away and, pointing at the squad of a dozen men who had dug the shallow grave shouted: ‘Don’t just stand there gawking, fill it in!’

The men set to work as Dennis stalked off to the edge of the clearing which had once been a small farmstead on the edge of the frontier, long since abandoned in this the ninth year of the Riftwar.

His gaze lingered for a second on the caved-in ruins of the cabin, the decaying logs, the collapsed and blackened beams of the roof. Saplings, already head-high, sprouted out of the wreckage. It triggered a memory of other ruins, but they were fifty miles from this place and he forced them out of his mind. That was a memory he had learned long ago to avoid

He scanned the forest ahead, acting as if he was waiting for the return of their scouts. Normally, Gregory would lead any scouting patrols, but Dennis wanted him close by, in case they had to beat a swift retreat. Years of operating successfully behind Tsurani lines had taught him when to listen to his gut. Besides, the scout who was out there was the only one in the company able to surpass Gregory’s stealth in the forest.

Resisting the urge to sigh, Dennis quietly let his breath out slowly and leaned against the trunk of a towering fir. The air was crisp with the smell of winter, the brisk aroma of pine, the clean scent of snow, but he didn’t notice any of that; it was as if the world around him was truly dead, and he was one of the dead as well. All his attention was focused, instead, on the sound of the frozen earth being shovelled back into the grave behind him.

The priest, startled by the irreverent display, had watched Dennis leave the group and then stepped up to Gregory’s side and glanced up at the towering Natalese, but Gregory simply shook his head and looked around at the company. All were silent, save for the sound of a few desultory shovels striking the icy soil; all of them were gazing at their leader as he walked away and passed into the edge of the surrounding forest.

Gregory cleared his throat again, this time loudly and having caught the men’s attention he motioned for them to get on with the work at hand.

‘He hates me,’ Father Corwin said, a touch of sadness in his voice.

‘No, Father. He just hates all of this.’ Gregory nodded at the wreckage of battle that littered the small clearing: the trampled-down snow – much of it stained a slushy pink – broken weapons, arrows, and the fifty-two Tsurani corpses that lay where they fell, including the wounded who had been finished off with a knife across the throat.

His gaze was fixed on the priest. ‘The fact that you accidentally caused this fight, that wasn’t your fault.’

The priest wearily shook his head. ‘I’m sorry. I was lost out here and didn’t know the Tsurani were so close behind me.’

Gregory stared straight into the pale-blue eyes of the old priest but the priest looked straight back at him, not flinching, not lowering his gaze even for an instant. Mendicant priests of any order, even those of the Goddess of Purity, had to be tough enough to live off the land and whatever bounty providence offered. Gregory had no doubt that the mace at the priest’s belt was not unblooded and that Father Corwin had faced his share of dangers over the years. Besides, Gregory was an experienced judge of men, and while this priest seemed meek at the moment, there was obvious hardness beneath the apparently mild exterior.

‘I wish I’d never left my monastery to come here and help out,’ the priest sighed, finally dropping his gaze. ‘We got lost, brothers Valdin, Sigfried and I. We were making for the camp of Baron Moyet, took a wrong turn on the trail and found ourselves behind the Tsurani lines.’

‘Only Rangers and elves travel these paths without risk of getting lost, Father,’ Gregory offered. ‘These woods are treacherous. It is said that at times the forest itself will hide trails and make new ones to lead the unwary astray.’

‘Brothers Valdin and Sigfried were captured,’ the priest continued, spilling out his story. ‘I escaped. I was off the trail, relieving myself, when the Tsurani patrol took them. I ran in the opposite direction after my brothers were dragged away. I was a coward.’

The Natalese Ranger shrugged. ‘Some might call it prudence, rather than cowardice. You denied the Tsurani a third prisoner.’

The priest still appeared unconvinced.

‘There was nothing you could have done for them,’ Gregory added with certainty, ‘except join them as a captive.’

Corwin seemed slightly more reassured. ‘It was foolish of me to have run, you’ll agree. Had I been more stealthy I’d not have led them to you. When I saw one of your men hiding off the side of the trail, I just naturally went straight to him.’

Gregory’s eyes narrowed. ‘Well, if he’d been doing a better job of hiding, you wouldn’t have seen him, then, would you?’

‘I didn’t know they –’ he pointed towards the Tsurani corpses littering the field ‘– were right behind me.’

Gregory nodded.

What should have been a clean, quick ambush incurring minimal loss had turned into a bloodbath. Eighteen men from the Marauders – nearly a quarter of Dennis’s command – were dead, and six more were seriously wounded. As it was, the engagement had been a Kingdom victory, but at far greater cost than was necessary.

The priest rambled on, starting his tale yet again. Gregory continued to study him. It was obvious the man was badly shaken. He was poorly dressed, wearing sandals rather than boots. A couple of toes were already showing signs of frostbite. His hands shook slightly, and his voice was near to breaking.

The priest fell silent, and took a long moment to compose himself. At last, he let out a long sigh, then looked over to Dennis who stood alone, at the edge of the clearing. ‘What is wrong with your commander?’ he asked.

‘His oldest friend is in that grave,’ Gregory said quietly, nodding down at the eighteen bodies lying side by side in the narrow trench hacked out of the freezing ground. ‘Jurgen served Dennis’s grandfather before he served the grandson. The land the Tsurani now occupy, part of it once belonged to Dennis’s family. His father was Squire of Valinar, a servant of Lord Brucal. They lost everything early on in the war. Word of the invasion hadn’t even reached Valinar before the Tsurani. The old Squire and his men didn’t even know who they were fighting when they died. Dennis and Jurgen were among a handful of survivors of the initial assault; Jurgen was his last link to that past.’ Gregory paused, transferring his gaze to Father Corwin. ‘And now that link is gone.’

‘I’m sorry,’ the priest replied softly, I wish none of this had ever happened.’

‘Well, Father, it happened,’ Gregory said evenly.

The priest looked up at him, and there was moisture in his eyes. ‘I’m sorry,’ he said one more time.

Gregory nodded. ‘As my grandmother said, “Sorry won’t unbreak the eggs.” Just clean up the mess and move on. Let’s find you some boots or you’ll lose all your toes before tomorrow.’

‘Where?’

‘Off the dead of course.’ Gregory indicated boots, weapons, and cloaks that had been stripped off the dead before they were buried. ‘They don’t need them any more, and the living do,’ he added matter-of-factly. ‘We honour their memory, but it’s no use burying perfectly good weapons and boots with them.’ He motioned with his chin. ‘That pair over there looks about your size.’

Father Corwin shuddered but went over and picked up the boots, the Natalese had indicated

As the priest untied his sandals, Alwin Barry, the newly-appointed sergeant for the company, approached the edge of the grave, picked up a clump of frozen earth and tossed it in.

‘Save a seat for me in Tith’s Hall,’ he muttered, invoking the old belief among soldiers that the valiant were hosted for one night of feasting and drinking by the God of War before being sent to Lims-Kragma for judgment. Barry bowed his head for a moment in respect, then turned away, heading over to the trail that went through the middle of the clearing, and called for the men to form up in marching order.

Others hurriedly approached the grave, picking up handfuls of dirt and tossing them in. Some made signs of blessing; one uncorked a drinking flask, raised it, took a drink then emptied the rest of the brandy into the grave and threw the flask in.

Burial was not the preferred disposition of the dead in the Kingdom, but more than one soldier rested under the soil over the centuries and soldiers had their own rituals for saying farewell to the dead, rituals that had nothing to do with priests and gods. This wasn’t about sending comrades off to the Halls of Lims-Kragma, for they were already on their way. This was about saying goodbye to men who had shed their blood alongside them just hours before. This was about saying farewell to brothers.