Полная версия:

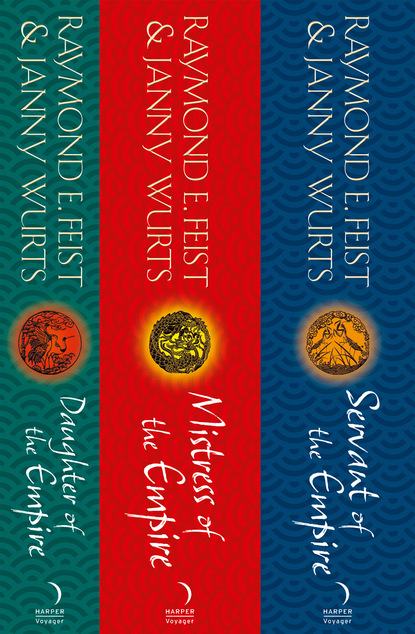

The Complete Empire Trilogy

The maids waited upon their mistress. Seated upon cushions in the chamber she still considered her father’s, Mara opened her eyes and said, ‘I am ready.’

But in her heart she knew she was not prepared for her marriage to the third son of the Anasati, and never would be. With her hands clenched nervously together, she endured as her maids began the tortuous process of combing out her hair and binding it with threads and ribbons into the traditional bride’s headdress. The hands of the women worked gently, but Mara could not settle. The twist and the tug as each lock was secured made her want to squirm like a child.

As always, Nacoya seemed to read her mind. ‘Mistress, the eye of every guest will be upon you this day, and your person must embody the pride of Acoma heritage.’

Mara closed her eyes as if to hide. Confusion arose like an ache in the pit of her stomach. The pride of Acoma heritage had enmeshed her in circumstances that carried her deeper and deeper into nightmare; each time she countered a threat, another took its place. She wondered again whether she had acted wisely in selecting Buntokapi as husband. He might be influenced more easily than his well-regarded brother Jiro, but he also might prove more stubborn. If he could not be controlled, her plans for the resurgence of Acoma pre-eminence could never be achieved. Not for the first time, Mara stilled such idle speculations: the choice was made. Buntokapi would be Lord of the Acoma. Then she silently amended that: for a time.

‘Will the Lady turn her head?’ Mara obeyed, startled by the warmth of the maid’s hand upon her cheek. Her own fingers were icy as she considered Buntokapi and how she would deal with him. The man who would take her father’s place as Lord of the Acoma had none of Lord Sezu’s wisdom or intelligence, nor had he any of Lano’s grace, or charm, or irresistible humour. In the few formal occasions Mara had observed Buntokapi since his arrival for the wedding, he had seemed a brute of a man, slow to understand subtlety and obvious in his passions. Her breath caught, and she forestalled a shudder. He was only a man, she reminded herself; and though her preparation for temple service has caused her to know less of men than most girls her age, she must use her wits and body to control him. For the great Game of the Council, she would manage the part of wife without love, even as had countless women of great houses before her.

Tense with her own resolve, Mara endured the ministrations of the hairdressers while the bustle and shouts through the thin paper of the screens indicated that servants prepared the great hall for the ceremony. Outside, needra bawled, and wagons rolled, laden with bunting and streamers. The garrison troops stood arrayed in brightly polished full armour, their weapons wrapped with strips of white cloth to signify the joy of their mistress’s coming union. Guests and their retinues crowded the roadway, their litters and liveried servants a sea of colour against the baked grass of the fields. Slaves and workers had been granted the day off for the festivities, and their laughter and singing reached Mara where she sat, chilled and alone with her dread.

The maids smoothed the last ribbon and patted the last gleaming tresses into place. Beneath coiled loops of black hair, Mara seemed a figure of porcelain, her lashes and brows as fine as a temple painter’s masterpiece. ‘Daughter of my heart, you have never looked so lovely,’ observed Nacoya.

Mara smiled mechanically and rose, while dressers slipped the simple white robe from her body and dusted her lightly with a powder to keep her dry during the long ceremony. Others readied the heavy embroidered silk gown reserved for Acoma brides. As the wrinkled old hands of the women smoothed the undergarment over her hips and flat stomach, Mara bit her lip; come nightfall, the hands of Buntokapi would touch her body anywhere he pleased. Without volition she broke into a light sweat.

‘The day grows warm,’ muttered Nacoya. A knowing gleam lit her eyes as she added a little extra powder where Mara would need it. ‘Kasra, fetch your mistress a cool drink of sa wine. She looks pale, and the excitement of the wedding is not yet begun.’

Mara drew an angry breath. ‘Nacoya, I am able to manage well enough without wine.’ She paused, frustrated, as her women hooked the laces at her waist and lower chest, temporarily constricting her breath. ‘Besides, I’m sure Bunto will drink enough for both of us.’

Nacoya bowed with irritating formality. ‘A slight flush to your face becomes you, Lady. But husbands don’t care for perspiration.’ Mara chose to ignore Nacoya’s cross words. She knew the old nurse was worried for the child she loved above all others.

Outside, the busy sounds told Mara that her household scrambled to finish the last-minute tasks. The august of the Empire and nearly overwhelming list of invited guests would gather in the great hall, seated according to rank. Since those of highest rank would be shown to their cushions last, the arrangement of the guests became a complex and lengthy affair that began well before dawn. Tsurani weddings occurred during the morning, for to complete so important a union in the waning part of the day was believed to bring ill luck to the couple. This required guests of modest rank to present themselves at the Acoma estate before dawn, some as early as four hours before sunrise. Musicians and servants with refreshments would entertain those seated first, while the priest of Chochocan sanctified the Acoma house. By now they would be donning their high robes of office, while out of sight a red priest of Turakamu would slaughter the needra calf.

The maids lifted the overrobe, with its sleeves sewn with shatra birds worked in rare gold. Mara gratefully turned her back. As attendants arranged her bows, she was spared the sight of Nacoya checking each last detail of the costume. The old nurse had been on edge since Mara chose to grant Buntokapi power over the Acoma. That Mara had done so with long-range hopes in mind did nothing to comfort Nacoya, what with Anasati warriors encamped in the barracks, and one of the Acoma’s most vigorous enemies living in style in the best guest chambers in the house. And with his brassy voice and artless manners, Buntokapi offered no reassurance to a servant who would shortly be subject to his every whim. And she herself would also, Mara remembered with discomfort. She tried to imagine being in bed with the bullnecked boy without shuddering, but could not.

Cued by a servant’s touch, Mara sat while the jewelled ceremonial sandals were laced onto her feet. Other maids pressed shell combs set with emeralds into her headdress. Restive as the needra calf being perfumed for sacrifice – so that Turakamu would turn his attentions away from those at the wedding – the girl called for a minstrel to play in her chambers. If she must endure through the tedium of dressing, at least music might keep her from exhausting herself with thought. If fate brought her trouble through this marriage to Buntokapi, she would find out soon enough. The musician was led in blindfolded; no man might look upon the bride until she began her procession to the wedding. He sat and picked out a soothing melody on his gikoto, the five-string instrument that was the mainstay of Tsurani composition.

When the last laces and buttons had been fastened, and the final string of pearls looped to her cuffs, Mara arose from her cushions. Blindfolded slaves bearing her ceremonial litter were led into the chamber, and Mara climbed into the open palanquin crafted solely for Acoma weddings. The frame was wound with flowers and koi vines for luck, and the bearers wore garlands in their hair. As they lifted the litter to their shoulders, Nacoya stepped between them and lightly kissed Mara on the forehead. ‘You look lovely, my Lady – as pretty as your own mother on the morning she wed Lord Sezu. I know she would have been proud to see you, were she alive this day. May you find the same joy in marriage as she, and be blessed with children to carry on the Acoma name.’

Mara nodded absently. As serving women stepped forward to lead her bearers through the screen, the minstrel she had summoned faltered in his singing and awkwardly fell silent. With a frown, the girl berated herself for carelessness. She had done the musician a discourtesy by leaving him without praise. As the litter moved from the chamber into the first empty connecting hall, Mara quickly dispatched Nacoya to give the man a token, some small gift to restore his pride. Then, wrapping her fingers tightly together to hide their shaking, she resolved to be more alert. A great house did not thrive if its mistress concerned herself with large matters only. Most often the ability to handle the petty details of life comprised an attitude that allowed one to discover the path to greatness; or so Lord Sezu had admonished when Lano had neglected his artisans for extra drill with the warriors.

Mara felt a strange detachment. The distant bustle of preparations and the arrival of guests lent a ghostly aspect to the corridors emptied for the passage of her litter. Wherever she looked she saw no one, yet the presence of people filled the air. In isolation she reached the main corridor and moved out of the estate house, into the small garden set aside for meditation. There Mara would pass an hour alone in contemplation, as she prepared to leave her girlhood and accept the role of woman and wife. Acoma guards in elaborate ceremonial armour stood watch around the garden, to protect, and to ensure the Lady would suffer no interruption. Unlike the bearers, they wore no blindfolds, but rather stood facing the walls, straining their hearing to the limit, alert, but not tempting ill luck by gazing upon the bride.

Mara turned her mind away from the coming ceremony, seeking instead to find a moment of calm, some hint of the serenity she had known in the temple. She settled gracefully to the ground, adjusting her gown as she settled on the cushions left for her. Bathed in the pale gold of early morning, she watched the play of water over the rim of the fountain. Droplets formed and fell, each separate in its beauty until it shattered with a splash into the pool beneath. I am like those droplets, thought the girl. Her efforts throughout life would, in the end, blend with the lasting honour of the Acoma; and whether she knew happiness or misery as the wife of Buntokapi would not matter at all when her days ended, so long as the sacred natami remained in the glade. And so long as the Acoma were accorded their rightful place in the sun, unshadowed by any other house.

Bending her head in the dew-bright stillness, Mara prayed earnestly to Lashima, not for the lost days of her girlhood, or for the peace she had desired in temple service. She asked instead for the strength to accept the enemy of her father as husband, that the name Acoma might rise once again in the Game of the Council.

• Chapter Seven • Wedding

Nacoya bowed deeply.

‘My Lady, it is time.’

Mara opened her eyes, feeling too warm for the hour. The cool of early morning had barely begun to fade, and already her robes constricted her body. She looked to where Nacoya stood, just before the flower-bedecked litter. Only a moment longer, Mara thought. Yet she dared not delay. This marriage would be difficult enough without risking the bad omen of having the wedding incomplete by noon. Mara rose without aid and re-entered the litter. She gestured readiness, and Nacoya voiced a command. The slaves removed their blindfolds, for now the bridal procession would begin. The guards surrounding the garden turned as one and saluted their mistress as the bearers lifted her litter and began their journey to the ceremonial dais.

The slaves’ bare feet made no sound as they carried Mara into the tiled hall of the estate house. Keyoke and Papewaio waited at the entrance and let the litter pass before they fell in behind, following at a watchful distance. Servants lined the doorways along the hall, strewing flowers to bring their mistress joy and health in childbearing. Between the doorways stood her warriors, an added fervour in each man as they saluted her passage. Several could not keep moisture from their eyes. This woman was more to them than their Lady; to those who had been grey warriors, she was the giver of a new life, against any expectation. Mara might give over their loyalty to Buntokapi, but she would always have their love.

The bearers halted outside the closed doors of the ceremonial hall while two maidens dedicated to the service of Chochocan pinned coloured veils to Mara’s headdress. Into her hands they pressed a wreath wound of ribbons; shatra feathers, and thyza reed, to signify the interdependence of spirit and flesh, of earth and sky, and the sacred union of husband and wife. Mara held the circlet lightly, afraid her damp palms might mar the silk ribbons. The brown-and-white-barred plumes of the shatra betrayed her trembling as four elegantly garbed maidens closed around her litter. They were all daughters of Acoma allies, friends Mara had known in girlhood. While their fathers might keep their distance politically, for this one day they were again her dear friends. Their warm smiles as the nuptial procession formed could not ease Mara’s apprehension. She might enter the great hall as the Ruling Lady of the Acoma, but she would leave as the wife of Buntokapi, a woman like all other women who were not heirs, an adornment to further the honour and comfort of her Lord. After a short ceremony before the natami in the sacred glade, she would own no rank, except through the grace of her husband.

Keyoke and Papewaio grasped the wooden door rings and pulled, and silently the painted panels slid wide. A gong sounded. Musicians played reed pipes and flutes, and her bearers started forward. Mara blinked, fighting tears. She held her head high beneath her veils as she was carried before the eyes of the greatest dignitaries and families in the Empire. The ceremony which would join her fate to that of Buntokapi of the Anasati was now beyond the power of any man to prevent.

Through the coloured veils the assembled guests appeared as shadows to Mara. The wood walls and floors smelled of fresh wax and resins, blending with the fragrance of flowers as the slaves bore her up the stairs of a fringed dais built in two layers. They set her litter down upon the lower level and withdrew, leaving her at the feet of the High Priest of Chochocan and three acolytes, while her maiden attendants seated themselves on cushions beside the stair. Dizzied by the heat and the nearly overpowering smoke from the priest’s censer, Mara fought to catch her breath. Though she could not see beyond the priests’ dais, she knew that by tradition Buntokapi had entered the hall simultaneously from the opposite side, on a litter adorned with paper decorations that symbolized arms and armour. By now he sat level with her on the priests’ right hand. His robes would be as rich and elaborate as her own and his face hidden by the massive plumed mask fashioned expressly for weddings by some long-distant Anasati forebear.

The High Priest raised his arms, palms turned towards the sky, and intoned the opening lines. ‘In the beginning, there was nothing but power in the minds of the gods. In the beginning, they formed with their powers darkness and light, fire and air, land and sea, and lastly man and woman. In the beginning, the separate bodies of man and woman re-created the unity of the gods’ thought from which they were created, and so were children begotten between them, to glorify the power of the gods. This day, as in the beginning, we are gathered to affirm the unity of the gods’ will, through the earthly bodies of this young man and woman.’

The priest lowered his hands. A gong chimed, and boy chanters sang a phrase describing the dark and the light of creation. Then, with the squeak of sandals and the rustle of silk, brocades, beads, and jewelled feathers, the assembled guests rose to their feet.

The priest resumed his incantation, and Mara fought the urge to reach beneath her veils and scratch her nose. The pomp and the formality of the ceremony made her recall an incident from her early girlhood, when she and Lano had come home from a state wedding similar to the one she sat through now. As children, they had played bride and groom, Mara seated on the sun-baked boards of a thyza wagon, her hair decked out in akasi flowers. Lano had worn a marriage mask of mud-baked clay and feathers, and the ‘priest’ had been an aged slave the children had badgered into wearing a blanket for the occasion. Sadly Mara tightened her fingers; the ceremonial wreath in her hands was real this time, not a child’s imitation braided of grasses and vines. Were Lanokota alive to be here, he would have teased and toasted her happiness. But Mara knew that inwardly he would have been weeping.

The priest intoned another passage, and the gong rang. The guests reseated themselves upon cushions, while the acolyte on the dais lit incense candles. Heavy scent filled the hall as the High Priest recited the virtues of the First Wife. As he finished each – chastity, obedience, mannerliness, cleanliness, and fecundity – Mara bowed and touched her forehead to the floor. And as she straightened, a purple-robed acolyte with dyed feet and hands removed one of her veils, white for chastity, blue for obedience, rose for mannerliness, until only a thin green veil for Acoma honour remained.

The gauzy fabric still itched, but at least Mara could see her surroundings. The Anasati sat to the groom’s side of the dais, just as the Acoma retinue sat behind Mara’s. Before the dais the guests were arrayed by rank. Brightest shone the white and gold raiment of the Warlord, who sat closest to the ceremony, his wife beside him in scarlet brocade sewn with turquoise plumes. In the midst of the riot of colours worn by the guests, two figures in stark black robes stood forth like nightwings resting in a flower garden. Two Great Ones from the Assembly of Magicians had accompanied Almecho to the wedding of his old friend’s son.

Next in rank should have been the Minwanabi, but Jingu’s presence was excused without insult to the Anasati because of the blood feud between Minwanabi and Acoma. Only at a state function, such as the Emperor’s coronation or the Warlord’s birthday, might both families be present without conflict.

Behind the Warlord’s retinue, Mara recognized the Lords of the Keda, the Tonmargu, and the Xacatecas; along with Almecho’s Oaxatucan and the Minwanabi, they constituted the Five Great Families, the most powerful in the Empire. In the next row sat the Shinzawai lord, Kamatsu, with the face of Hokanu, his second son, turned handsomely in profile. Like the Acoma and the Anasati, the Shinzawai were counted second in rank only to the Five Great Families.

Mara bit her lip, the leaves and feathers of her marriage wreath trembling. Above her the High Priest droned on, now describing the virtues of the First Husband while the acolytes draped necklaces of beads over the paper swords of Bunto’s litter. Mara saw the red and white plumes of his marriage mask dip as he acknowledged each quality as it was named, being honour, strength, wisdom, virility, and kindness.

The gong chimed again. The priest led his acolytes in a prayer of blessing. More quickly than Mara had believed possible, her maiden attendants arose and helped her from her litter. Bunto arose also, and with the priest and acolytes between them stepped down from the dais and bowed to the gathered guests. Then, in a small procession that included Buntokapi’s father, the Lord of the Anasati, and Nacoya, as the Acoma First Adviser, the priest and his acolytes escorted bride and groom from the hall and across the courtyard to the entrance of the sacred grove.

There servants bent and removed the sandals of Mara and Buntokapi, that their feet might be in contact with the earth and the ancestors of the Acoma as the Lady ceded her inherited rights of rulership to her husband-to-be. By now the sun had risen high enough to warm the last dew from the ground. The baked warmth of the stone path felt unreal beneath Mara’s soles, and the bright birdsong from the ulo tree seemed the detail of a childhood dream. Yet Nacoya’s grip upon her arm was quite firm, no daydream. The priest chanted another prayer, and suddenly she was walking forward with Buntokapi, a jewelled doll beside the towering plumage of his marriage mask. The priest bowed to his god, and leaving his acolytes, and the Lord, and the Acoma Chief Adviser, he followed the couple into the glade.

Rigidly adhering to her role, Mara dared not look back; if the ritual had permitted, she would have seen Nacoya’s tears.

The procession passed the old ulo’s comfortable shade and in sunlight wended through the flowering shrubs, low gates, and curved bridges that led to the Acoma natami. Woodenly Mara retraced the steps she had taken not so many weeks earlier, when she had carried the relics to mourn her father and brother. She did not think of them now, lest their shades disapprove of her wedding to an enemy to secure their heritage. Neither did she look at the man at her side, whose shuffling step betrayed his unfamiliarity with the path, and whose breath wheezed faintly behind the bright red-and-gold-painted features of the marriage mask. The eyes of the caricature stared ahead in frozen solemnity, while the eyes of the man darted back and forth, taking in the details of what soon would be rightfully his as Lord of the Acoma.

A chime rang faintly, signalling the couple to meditate in silence. Mara and her bridegroom bowed to the godhead painted on the ceremonial gate, and stopped beneath at the edge of the pool. No trace of the assassin’s presence remained to defile the grassy verge, but a canopy erected by the priests of Chochocan shaded the ancient face of the natami. After a session of prayer and meditation, the chime rang again. The priest stepped forward and placed his hands on the shoulders of the bride and groom. He blessed the couple, sprinkled them lightly with water drawn from the pool, then paused, silent, while the vows were spoken.

Mara forced herself to calm, though never had the exercise learned from the sisters of Lashima come with such difficulty. In a voice of hammered firmness, she spoke the words that renounced her inherited birthright of Ruling Lady of the Acoma. Sweating but steady, she held fast while the priest tore away the green veil and burned it in the brazier by the pool. He wet his finger, touched the warm ash, and traced symbols upon Bunto’s palms and feet. Then Mara knelt and kissed the natami. She remained with her head pressed to the earth that held the bones of her ancestors, while Buntokapi of the Anasati swore to dedicate his life, his honour, and his eternal spirit to the Name Acoma. Then he knelt beside Mara, who finalized the ritual in a voice that seemed to belong to a stranger.

‘Here rest the spirits of Lanokota, my brother; Lord Sezu, my natural father; Lady Oskiro, my natural mother: may they stand as witness to my words. Here lies the dust of my grandfathers, Kasru and Bektomachan, and my grandmothers, Damaki and Chenio: may they stand as witness to my deed.’ She drew breath and managed not to falter as she recited the long list of ancestors back to the Patriarch of the Acoma, Anchindiro, a common soldier who battled Lord Tiro of the Keda for five days in a duel before winning the hand of his daughter and the title of Lord for himself, thus placing his family second only to the Five Great Families of the Empire. Even Buntokapi nodded with respect, for despite his father’s formidable power, the Anasati line did not go as far back in history as the Acoma. Sweat slid down Mara’s collar. With fingers that miraculously did not shake, she plucked a flower from her wreath and laid it before the natami, symbolizing the return of her flesh to clay.

The chime sounded, a mournful note. The priest intoned another prayer, and Bunto spoke the ritual phrases that bound him irrevocably to the Name and the honour of the Acoma. Then Mara handed him the ceremonial knife, and he nicked his flesh so the blood flowed, beading in dusty drops upon the soil. In ties of honour more binding than flesh, of previous kinship, more binding than the memory of the gods themselves, Buntokapi assumed Lordship of the Acoma. The priest removed the red and gold marriage mask of the Anasati; and the third son of an Acoma enemy bowed and kissed the natami. Mara glanced sideways and saw her bridgeroom’s lips curl into an arrogant smile. Then his features were eclipsed as the High Priest of Chochocan slipped the green marriage mask of the Acoma onto the new Lord’s shoulders.