Полная версия:

The Making of Us

You are all here because you have shown through competition that you have outstanding talent and outstanding potential. That should not make you smug or complacent because it gives you a responsibility – to make as much of those gifts as you possibly can. You will enjoy some great teaching here, but what you make of your potential will be to a large extent up to you. What we do together, in this school, is to aim as high as we can; to use our capability in the best way – not just when things go well, but when we stumble and things get harder too.

I would return to this idea of managing our own expectations of ourselves repeatedly when talking to both the students and staff, through the year. In some ways it became one of the most important messages of all in the constant task of balancing a stretching, challenging and exciting education with the fact that we all have edges to our capability and striving for excellence has to be tempered with an awareness of our individual limits. A happy balance is found when demands are great enough for energy and confidence to flow but not so great that they tip us over into stress and anxiety. In a school like St Paul’s, where the pupils are prodigiously talented, that balance, I found, had to be struck and restruck. Aspirations should be set high while being tempered with the active building of self-esteem and confidence, especially in girls who, in my experience, are inclined (partly because of the high standards they set themselves) to doubt themselves more than they should. Equally, that confidence mustn’t spill over into complacency or arrogance. One girl said to me privately, ‘I hate it when people say how clever we are …’ She felt it as a pressure, an unhelpful label. Only through the constant conversation could that balance be achieved and kept in fruitful equilibrium.

School assemblies, whether at the start of the year or not, rather than being merely ‘a hymn, a prayer and a bollocking’ – as one distinguished headmistress colourfully described them – can inform and set the tone, convey values and ethos as well as sometimes amuse and entertain. That is why I fought to keep the whole-school assembly (three times a week by the time I left the school) and would defend its value fiercely. Assemblies have been the vehicle through which I’ve conveyed some of the most important, and sometimes most difficult, messages during my two headships, including on three occasions, tragically, telling the school about the death of a pupil or member of staff. One of these was the death of my predecessor, Elizabeth Diggory, who survived the return of cancer for only eight months of her retirement.

Elizabeth, an elegant and gracious woman, shyer than her height and bearing made people think and perhaps someone who did not altogether relish standing up and addressing 700 or so difficult-to-impress teenagers, once told me that assemblies, these ten-minute gatherings of the whole school at 8.40 in the morning, were times when the Paulinas ‘expected to be entertained intellectually’. Privately resolving that this sense of entitlement would be something to coax them out of, I used the early assemblies of my headship not so much for any grand pronouncements or displays of intellectual skill but to introduce myself as a person. It was important as part of getting to know each other to show that the ‘high mistress’ was not just a formal figurehead in academic dress, only slightly more animated than the portraits of her predecessors lining the walls, but an individual with interests, tastes and opinions and importantly, flaws – someone you might get to know. At the start of my first term, for example, it had been twelve months since the news of my appointment had become public. Plenty of time for myths of various kinds to precede me, not all of which I scotched straight away. I came from a school in Potters Bar, Hertfordshire: where was that exactly – in the Midlands somewhere? Was it true that I planned to introduce uniform into this highly individualistic school, where the pupils all choose their own clothes? Did I really run marathons? While allowing certain myths to continue – the uniform one added a certain frisson – I talked to the girls and staff about my interests, my experiences – and occasionally my mistakes. Over the first few years, this involved forays into Thomas Hardy’s novels (my best attempt at a Dorset accent); a challenge to one of my predecessor’s adages that a Paulina should be taught to ‘think and not cook’ (they can of course do both), which involved baking a loaf of bread on the stage in my trusty Panasonic bread machine (the fire alarm having been briefly disabled); and an account of my re-education by the City of London Police following a speeding fine. Whether these stories ‘entertained intellectually’ was for others to say: what I hope they did was to give some sense of the high mistress as a human being, with preferences, foibles and failings, just like anyone else.

The various rituals of the start of the year almost done, I always felt relieved to feel the term begin to get into its rhythm. But the patterning of the academic year and the frame that it gave to everything we did was always there. What other kind of life is marked by such a formal structure? In the UK, three ‘terms’ are divided by three holidays still – in most schools – aligned traditionally to the Christian calendar: we have the Christmas holidays, the Easter holidays and then the long summer break. In the midst of each term there are the half-term holidays, sometimes lasting for a week but in many cases for two in the autumn. A regular and predictable pattern, published by most schools a year in advance. Before the current move by some families towards taking holidays in term time, when flights and accommodation are generally far cheaper, this was an absolute red line that could not be crossed. As high mistress I would write a letter to parents at the start and end of most terms and one of my crisper efforts included the words: ‘Thank you for not asking me if you can leave two days early at the end of term because the flights are less crowded.’ But even then it did not entirely work. And my cause certainly wasn’t helped when I made my own mistake about holiday dates shortly after Adam, my son, started at a new school. Thinking to celebrate my mother’s birthday, I had booked a five-day trip to Venice for my mother, myself and the children at summer half term. Half term is always a week, isn’t it? Only at my son Adam’s school, I discovered a week before departure, that half term was actually only two days. Paralysed with embarrassment, I picked up the phone to launch a major charm offensive on the deputy head. ‘I thought it would have real educational value, Carl,’ I wheedled, hoping desperately this wasn’t going to go right round the staffroom the minute I put the phone down. ‘That’s all right, Clarissa – these things happen,’ came the reply after a short pause, during which I realised Carl had been stifling amusement sufficient for his broad grin not to be audible down the phone. We went to Venice: the sun shone, the water slapped against the jetty outside the hotel. I still have the picture of my mother sitting on the steps of Santa Maria della Salute and of Adam in his gondolier’s hat. But I didn’t make that mistake again, and I always remembered to be particularly respectful to Adam’s deputy head. Unsurprisingly, I have since been a little more tolerant of the occasional ‘diary moment’.

An aspect of the school year which causes more widespread problems for parents is the dogged idiosyncrasy of individual schools. A year or so ago I read a very sensible letter from a grandfather who was concerned about the strain on his daughter, struggling as she was to juggle the demands of the slightly different term and holiday dates of her four school-aged children. I’m no mathematician but you can quickly work out that this poor woman was racing round trying to avoid the Carl conversation over no fewer than forty-eight potential dates during the year. And that’s before she started trying to take account of the extra holidays, special half-days and INSET (in-service training) days that are squeezed in to confuse parents by these ‘constantly on holiday’ teachers. It shouldn’t be beyond independent schools in the same city – London, say – to agree to have the same holiday dates, should it? Try suggesting it. I somewhat naively did so at a regional heads’ meeting, where people looked at me with that indulgent incredulity reserved for those asking why Oxford and Cambridge colleges can’t adopt consistent admissions procedures. Feeling the weight of centuries of baroque and inexplicable process settle like a vast smothering tapestry over my head, I said no more.

We have the formal structure of years and terms. And then there is the shape of each day. As Larkin puts it with beautiful simplicity:

What are days for?

Days are where we live.

They come, they wake us

Time and time over.

They are to be happy in:

Where can we live but days?[1]

In a school, the regular set pattern of each day is often punctuated and symbolised by the ringing of bells for lessons and break time. Some might think this restrictive: imagine being an adult and still having your day determined by a bell every half an hour or so. In my experience, as a teacher, it’s a way of making sure you have the most exceptionally productive day. You might long for a precious free period to get your marking done, but it isn’t possible to find you’ve wasted over half an hour noodling around on your phone if you have twenty eager faces in front of you ready to discover the Russian language and you only have that particular thirty-five minutes in which to help them do so. A class cannot be kept waiting! And again, there is comfort in the familiar regularity. We conducted an experiment at St Paul’s to see whether to change the shape of the school day, but after a lengthy and highly consultative process, we decided more or less to keep things as they were. There was something in the rhythm and pattern that seemed balanced, as if we were biologically adapted: the changed day felt by turns piecemeal and baggy, lacking in proper flow – just wrong, somehow.

Living to the discipline of the academic year, week and day has its frustrations and constraints. At the same time, it provides a familiar rhythm from which we can draw confidence, security and comfort. I believe that the pattern and structure which we become used to at school meets a more fundamental and lifelong human need: to feel ourselves located, grounded, placed in relation to the world around us. To lack that – and sometimes in life if we are untethered from our moorings and face periods of confusion or loss – produces a feeling very like the homesickness we might recall from childhood. In a world of expanding possibilities and greater uncertainty we are fortunate that in schools, our children’s lives still have this regular pattern: its cycle of peaks and troughs of concentration, anticipated special days and traditional events, giving the school year a safe and familiar rhythm. And just as a school encourages ambition and challenges its pupils to take intellectual risks and aim high, it balances this with a longer perspective, with patience and compassion. If you mess things up, there will be a chance to start again: next half, next term, next year.

CHAPTER 2

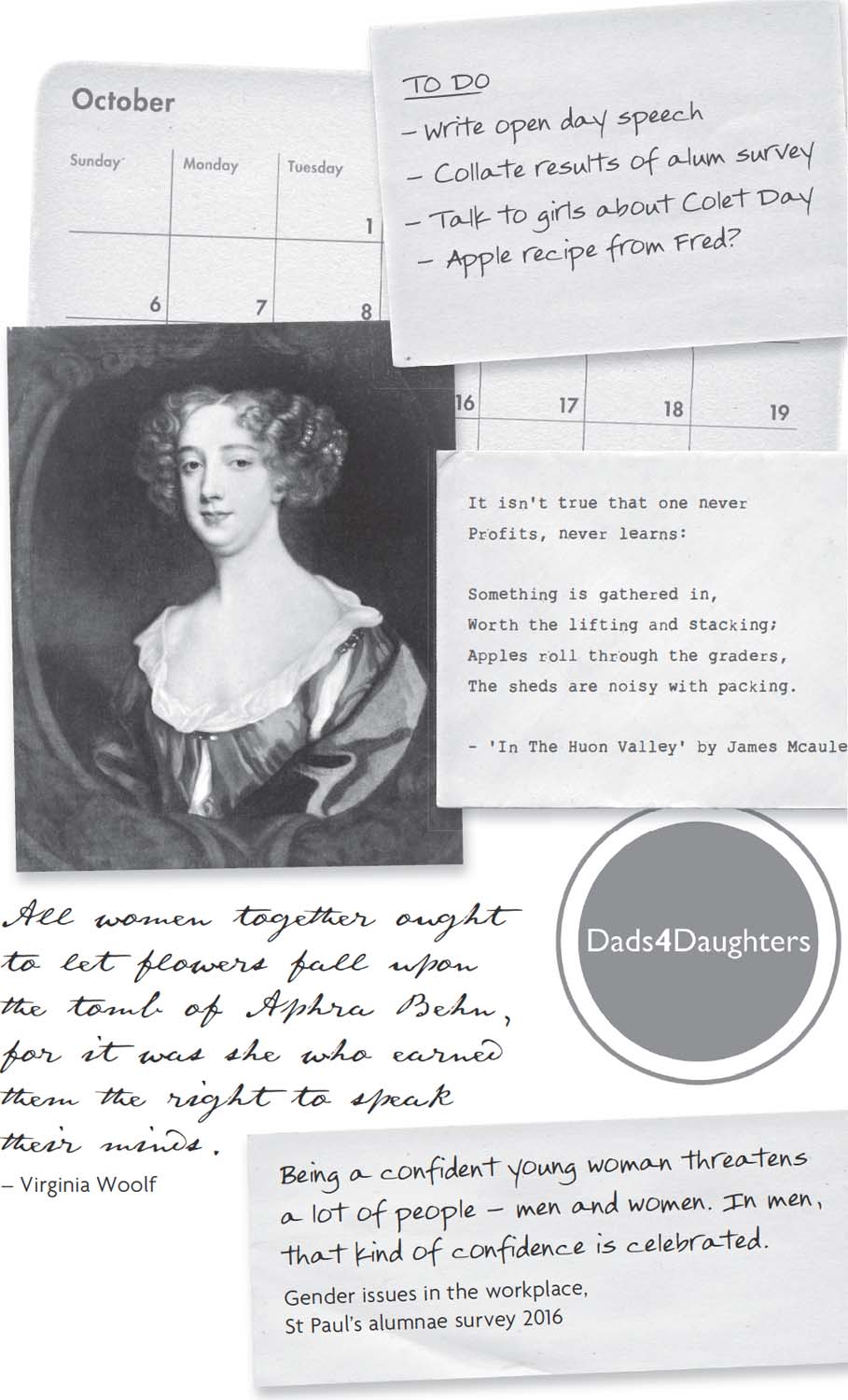

October

A question of gender – still vindicating the rights of women?

The leaves are turning, the wind is gusting and I arrive in the office having lost yet another umbrella. As October starts, the academic year is well underway, corridors are humming with conversation and everyone is settling into the familiar rhythm of the term. In the admissions department, thoughts are already turning to next academic year, this being the month of open days for families considering applying to the school, so it’s time to brush up my speech for the prospective parents. It’s also the annual service in St Paul’s Cathedral, known as Colet Day, held jointly with St Paul’s Boys’ School, where each year we celebrate our foundation. Two reasons for me to be reflecting on John Colet’s vision for education, the case for single-sex schools, the education of girls in particular and what happens when girls will not be girls: in other words, the wider issue of gender identity schools are facing today.

Dean of St Paul’s, member of the Worshipful Company of Mercers and pioneering educationalist, John Colet used the fortune he inherited from his father to found St Paul’s boys’ school in 1509. At this time, the height of the Renaissance in England, Colet counted among his friends the great Dutch scholar Erasmus, who assisted both with writing textbooks and a Latin grammar for the school and with appointing staff. Colet also knew Thomas More, another progressive thinker and advocate of the education of women – his own daughter Margaret Roper becoming a distinguished classical scholar and translator. Amongst the early high masters of St Paul’s was Richard Mulcaster, appointed in 1596, who wrote extensively on education, advocating proper training for teachers and the development of a curriculum determined by aptitude rather than age. He too thought women should have access to formal education, including attending university. Another contemporary, Robert Ascham, became tutor to Queen Elizabeth I and was the author of The Scholemaster, published in 1570 after his death and which, as well as being a treatise on how to teach Latin prose composition, explored the psychology of learning and the need to educate the whole person. These were forward-thinking men. Widely travelled himself, Colet believed that education generally and his school in particular should be for the children ‘of all countres and nacions indifferently’ and that it should, as the humanists of the Renaissance believed, concentrate on developing the life of the mind through the study of Latin and Greek and the scholarship of antiquity, all of this becoming more achievable with the advent of printing. Colet was ambitious for his school as an institution of learning but also as an instrument of social change. Given this and the cultural climate in which the school was founded – a time of burgeoning exploration, discovery and scholarship – it is perhaps surprising that it took another 400 years for the Mercers’ Company to establish a girls’ school. But in 1904 they did, and as I was fond of telling prospective parents, by the early twenty-first century, we had more than made up for the time lost, the two schools by then equally established and known for their breadth of education and academic excellence. As a result of a developing bursary programme, they were also no longer just the preserve of the wealthy, but educating a widening range of bright children from across London, reflecting the cultural diversity of a capital city.

To the contemporary Paulina, with her characteristic wit and taste for unexpected juxtapositions, John Colet is part embodiment of her love of tradition and part teen icon. Colet’s unblinking black bust, staring straight out and dressed in austere sixteenth-century clericals, presiding over the long, black-and-white chequered corridor known as ‘The Marble’, often appears in the background of selfies, with added sunglasses or perhaps a Father Christmas hat. ‘John Colet rocks!’ the girls exclaim with affectionate irreverence. And Colet’s legacy is extraordinarily alive in the two schools today, where his vision finds fresh and contemporary expression. I feel sure that the addition of the girls’ school is something of which he would have wholeheartedly approved.

Colet Day itself is a high point in the calendar anticipated with great excitement. The vast cave of St Paul’s Cathedral with its unnerving acoustic (open your mouth and you think you are singing on your own – very disconcerting) is packed with proud parents and in the front rows, under the echoing dome, the two schools sit, flanked by their tutors. A monumental rustling as the organ swells and the service begins, the clergy processing and everyone rising to their feet, anticipating the ritual that is to come. Moving to the lectern to speak my allotted words (the high master and high mistress alternate their lines each year, in careful observance of equality) I wonder again about the respective characters of these two schools, with their brother and sister relationship of familial closeness and sibling rivalry, and whether one day they will become one. For the time being, Colet Day brings the two schools together in symbolic unity and the question dissolves unspoken in the air.

Whatever form schools take in the future, the length of time it has taken us to take seriously the education of girls must remain one of history’s great opportunity costs. We can reflect that despite the efforts of early pioneers, for all the women who have risen to prominence in the world, there are so many more whose capability and contribution have rested either unsung, unrealised or unfulfilled. That’s half the potential of any single generation. And when we talk about the education of women today, even though so much progress has been made, there is still always an underlying sense that we are righting a wrong, catching up with something which has been given insufficient importance and which now therefore needs special explanation or attention. As part of this, we are also still working out how women fit into the public, professional world and therefore to what kinds of roles they are best suited: are they bringing something different from men to strategy, to leadership, to getting things done? Should the fact of your gender be celebrated or ignored? While the debate continues, at school level the emphasis is overwhelmingly on integration. Worldwide, the modern default school model that is regarded as more ‘natural’ is not single-sex education but having boys and girls learning alongside one another in a co-educational setting. Single-sex schools might have been all right a hundred years ago, when girls were only just progressing from being taught refined accomplishments by governesses in the safe and sequestered setting of their homes, but that time has passed. This is the twenty-first century. Aren’t single-sex schools just an anachronism, encouraging outdated ways of thinking and walking out of step with the real world?

This is a question that cannot be sidestepped with sentimental appeals to custom and tradition. If single-sex education is to have a future, for girls or indeed for boys, it has to be not merely nice, but necessary. This means being based on something more than a nostalgic affection for how things used to be when time stood still and a school was its own little citadel, shut off from the real world like Hogwarts or St Trinian’s. Boys’ schools, perhaps because many are so long established, have not often felt the need to explain overtly the advantages they offer boys. Why would you, if you’ve been going strong for hundreds of years and produced many of the people (men) who have been the opinion formers and leaders of their day? And perhaps too with the prevailing attention being on addressing the needs of women, it hasn’t been easy for them to do so. As more and more boys’ schools admit girls to buttress their finances and academic profile, and boys-only establishments become a rarity, a few are now advancing their unique proposition with more clarity. Girls’ schools on the other hand have been in campaign mode from the start: the only way to educate girls properly is to educate girls only. But is it? Any movement championed by women for women faces challenges, not least having to weather being caricatured by some as shrill, desperate, unfeminine or just downright hoydenish – think of the suffragettes. At the same time advocates for girls’ schools have not always helped themselves by choosing the most robust and persuasive grounds on which to prevail. I’m a passionate believer myself in women’s education and empowerment, but not every argument for having girls educated separately is necessarily convincing and we do ourselves no good by appearing to grasp any new ‘proof’ instrumental to our cause.

I’m particularly dubious, for example, about there being a scientific, biological justification for girls’ schools. In a no doubt well-intentioned attempt to ensure their immortality, a body of so-called ‘science’ has developed arguing that girls need to be taught separately because they are neurologically different – they literally have differently wired brains and therefore it follows that they require teaching in special ways that would be wasted on boys but can make differently wired girls flourish. We can call this the ‘nature’ argument. A few years ago, for example, advocates of girls’ schools latched with great enthusiasm onto the work of the American psychologist JoAnn Deak and her book Girls Will Be Girls. Here was the ‘proof’ the girls’ school movement had been looking for. Along with a great deal of very sensible and pragmatic advice about the raising of daughters, Deak – renowned, as the cover blurb says, for her knowledge of ‘what makes girls tick’ – makes this claim: ‘brain research now clearly shows that the structure of the male and female brain is different at birth, apparently the result of oestrogen or testosterone shaping it in utero. In other words, female brains have more neurons in certain areas than male brains as a result of having more estrogen bathing them during fetal development.’[1] Bathed in oestrogen in the womb, the female brain also has a predisposition for effectiveness in certain cognitive areas: language facility, auditory skills, fine motor skills and sequential/detailed-thinking. Deak goes on to argue that the amygdala, the emotional centre of the brain, is especially sensitive in females, making them experience more frequent and more intense emotions. Given the biologically different nature of the male and female brains, both genders, she advises, need to spend time on activities that are counter to their neurological grain. To grow into properly balanced individuals, little girls should spend more time with building blocks and little boys in the drawing corner, and so on. You can see at once how its central point – that girls are wired differently – could be used by advocates of girls’ schools to propose an entire curriculum and approach to learning that would be uniquely girl-centred, justified – indeed essential – because the science says they need it.

Not everyone is so convinced by this correlation. The idea that men and women are biologically different in more ways than the obvious is explored with some vigour by Cordelia Fine in her wonderfully acerbic book, Delusions of Gender. The clue is in the title: Fine ruthlessly demolishes what she sees as the dubious scientific proofs of the neurological differences between men and women and the so-called male and female brains. Distinguishing between the brain as a biological structure and the more complex notion of the mind, and surveying hundreds of years’ worth of evidence which has been used to build the concept of ‘neurosexism’, she points to the fact that in a world where we love referencing gender differences and learn to do so from very early childhood, time and time again those differences are seen to be derived as much – or more – from our own preconceptions, born of social customs about the characteristics of gender, as from any actual physiological evidence. In other words, for her it’s about nurture rather than nature.

Fine argues that men and women behave and perform certain tasks differently, and might presumably also learn differently, not so much because of any intrinsic neurological difference but because they are fulfilling a social expectation. Society and the self thus become reciprocally defining – the one informs and reinforces the other. Here for example is what she has to say about housework and who does it:

In families with children in which both spouses work full time, women do about twice as much childcare and housework as men – the notorious ‘second shift’ … You might think that, even if this isn’t quite fair, it’s nonetheless rational. When one person earns more than the other then he (most likely) enjoys greater bargaining power at the trade union negotiations that, for some, become their marriage. Certainly, in line with this unromantic logic, as a woman’s financial contribution approaches that of her husband’s, her housework decreases. It doesn’t actually become quite equitable, you understand. Just less unequal. But only up to the point at which her earnings equal his. After that – when she starts to earn more than him – something very curious starts to happen. The more she earns, the more housework she does …