Полная версия:

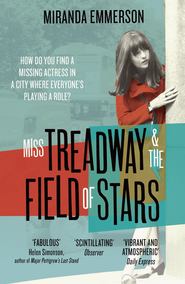

Miss Treadway & the Field of Stars

She walked back to Lanny’s dressing room. The cup of tea sat on the table untouched. Was Iolanthe ill?

Of course, everyone expected Lanny to arrive by the interval. She must have gone off for the day and got stuck in traffic. That’s what made most sense. But the interval came and went and there was no Iolanthe.

Leonard phoned round the hospitals in case there had been an accident. He phoned The Savoy again and spoke to the desk clerk. Iolanthe hadn’t been in her room since Friday night.

The show came down at ten to ten. The audience cheered Agatha, though many had left at the interval since catching sight of Iolanthe Green had been their main reason for buying the tickets. Leonard called a meeting on the stage. The cast sat on chairs in a circle. Anna sat with the other dressers and the crew on the floor. Leonard told everyone about his call to The Savoy.

‘Iolanthe has to be considered a missing person. I’ve already called the police. If she hasn’t turned up by tomorrow morning they’ll be coming down to interview us here. The show will keep running but management are going to keep an eye on cancellations. If we’re not playing to at least forty per cent attendance they may take us off in another week. Don’t worry about that now, but I need to give you that warning so you’re prepared. No one of Iolanthe’s description has been admitted to any of the big hospitals. I’m going to see that as a good thing. You all did well tonight. Go home. Get some sleep. Company meeting at four tomorrow followed by a line run if it’s understudies again. Okay. Off you go!’

***

On Tuesday the papers were full of Iolanthe’s disappearance. The Mirror asked if Brady and Hindley had inspired a copycat murder in London. The Sun wanted to know if Iolanthe had fallen prey to a gang of Soho people smugglers. The Daily Express asked its readers to join police in hunting for the glamorous starlet. The Daily Telegraph wondered if fragile, unmarried Miss Green had run away from the pressures of fame.

On Wednesday afternoon, as the company of understudies gathered for yet another line run, BBC Radio News arrived to interview Leonard about Lanny’s disappearance. Anna stood in the green room beside the transistor radio and listened to Leonard intoning his worries and incomprehension at six o’clock and then again at ten. Each time she heard someone familiar speak, or read someone she knew quoted in the paper, they – the people involved, the events – became less familiar. She was starting to see it as a story herself. The story of how Lanny disappeared.

On Thursday The Times wanted to know why women weren’t safe to walk the streets of Theatreland and the Guardian wanted to know why so much attention was being paid to one wealthy actress when in the past week alone two hundred ordinary people had gone missing without any great fanfare at all.

On Friday, as Londoners gathered to burn effigies of Guy Fawkes, police were called to a disturbance at a flat in Golden Square. When they arrived they found a young male prostitute called Vincent Mar lying on the front steps having sustained a terrible head wound. The police arrested a middle-aged man who was the tenant of the flat they’d been called to attend. The man’s name was Richard Wallis and he happened to be a Junior Minister of State for Justice in Her Majesty’s Government. By the time Wallis had been released – without charge – late on Saturday night, the papers had got hold of the scandal and Iolanthe was about to be knocked quite definitively off the front pages.

Monday, 8 November

In West End Central police station, up on Savile Row, Inspector Knight had been co-ordinating a well-resourced search effort for Iolanthe but now he was running out of ideas. Statements had been taken and double-checked, posters had been mounted in prime locations, hospitals had been phoned and visited. Nobody, it seemed, absolutely nobody, had seen Miss Green.

Over the course of a fraught weekend, in which he had seen nothing of his wife or children, Knight had been instructed firmly by the Home Office that he was to scour Soho for other possible assailants of young Mr Mar who had – to the relief of many – failed to regain consciousness after the attack. But the majority of Knight’s men were assigned to the hunt for the missing actress.

The Sunday papers had attempted to try and convict Mr Wallis right there on the newsstands and pressure from the offices of government was increasing. So at 9 a.m. on Monday, Inspector Knight called into his office a detective sergeant by the name of Barnaby Hayes.

‘The government is defecating in its collective knickers, Hayes.’

‘I’m sure it is, sir.’

‘I have until next Sunday to find at least one fully fashioned scumbag who might have tried to kill, rob or bugger Vincent Mar. I also have to hope the bloody man’s about to die, because if he wakes up and recounts a night of ecstasy with Mr Wallis we’re all fucked.’

‘Sir.’

‘The worst of it is I still have to pretend to care about Iolanthe Green when any fool can see that the woman’s obviously done herself in and hasn’t had the decency to leave her body somewhere handy.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘You’re the closest thing I have to competent in my department, Hayes. Don’t fuck up and don’t talk to any press.’

‘Sir.’

‘Find the body. Close the case. We have better things to be doing.’

Barnaby Hayes picked up the small pile of manila files and carried them out of the office to his desk. He was a meticulous and careful officer, a player by the rules. He had distinguished himself in the eyes of Knight by working long hours and never once trying to cut corners or claim he’d done work when he hadn’t. His name – as it happened – was not Barnaby at all, but Brennan. He had cast this particular mark of Irishness away from him when he joined CID.

He opened the files and rearranged their contents. He knew from bitter experience that not everyone in the department was as assiduous as he was and he could see no other way ahead but to start from scratch and re-interview everyone connected to Iolanthe. He cast his eyes down the list of eyewitnesses from the Saturday she had disappeared. The name at the top of the list was Anna Treadway. He dialled her number.

Miss Treadway

Anna Treadway lived on Neal Street in a tiny two-bed flat above a Turkish cafe. She went to bed each night smelling cumin, lamb and lemons, listening to the jazz refrain from Ottmar’s radio below. She woke to the rumble and cry of the market men surging below her window and to the sharp, pungent smell of vegetables beginning to decay.

At seven o’clock most mornings of the week she would make the walk to buy a small bag of fruit for her breakfast. Past the Punjab India restaurant, where the smell of flatbread was just starting to escape the ovens. Past the vegetable warehouses with their arching, pale stone frontages. Past the emerald green face of Ellen Keeley the barrow maker. Past the dirty oxblood tiles of the tube station where Neal Street ended and James Street began. Past Floral Street where the market boys drank away their wages and down, down, down to the Garden. Covent Garden: once the convent garden. Now so full of sin and earth and humanity. Still a garden really, after all these years.

The roads around it were virtually impassable most mornings, a deadly tangle of horses, dogs, cars and old men whose thick woollen cardigans padded out their frames until they looked like overstuffed rag dolls with pale, needle-pricked faces. Men who pulled great barrows – like floats from a medieval carnival – piled with sweetcorn and plums, leeks and potatoes and fat red cabbages that gleamed and glistened like blood-coloured gems. Men who balanced on their heads thirty crates of lavender that swayed and bowed as they walked and left the perfume trail of distant fields everywhere they went. Covent Garden, so sensual and unkempt: a temple to something, though no one could tell you quite what. Money. Nature. London. Anna sometimes thought that it acted like a city gate, announcing London’s size and grandiosity to all who visited there. Look at us, it said, look what it takes to feed us all. How mighty we must be when roused. How indomitable.

Through the garden and into the house she went. Into the vaulted space of the indoor market and through the crush of tweed jackets and donkey jackets and macs.

‘Sorry, love.’ ‘Mind yourself.’ ‘MUSTARD GREENS!’

In this world of men a woman’s voice could become lost, clambering high and low to find its place between the layers of bass and tenor sound. ‘Black— Goose— App—.’ The syllables of the woman in the dark red pinafore were eaten by the whole, swallowed down like soup in this dark, confusing dragon’s belly of a place. Anna handed the woman her pennies and the woman gave her a paper bag of blackberries in return. How strange, Anna thought it was, to pay for blackberries when she had gone every September as a child to the railway cutting at the bottom of town to fill her skirt for free.

‘Everything can be given a price if someone chooses,’ her mother said. ‘It doesn’t have to make sense to us, Anna. So little of the world makes sense.’

Back home in the little flat, she shared her early-morning rituals with an improbably blonde American called Kelly Gollman who worked as a dancer in a revue bar in Soho and who rented the better of the two bedrooms from Leonard Fleet, Anna’s boss who lived in the flat above.

Anna had never seen Kelly dance and Kelly was careful never to ask her if she might one day come into the club. Both had the uneasy feeling that they were not on the same level as the other: Kelly taking her clothes off for boozy businessmen and Anna carrying clothes and cups of lemon tea for proper actresses in a theatre with dark gold cupids above the door. Anna had the kind of job that one could tell one’s parents about and she was English and she had a leather-bound copy of Shakespeare on her bedside table.

Sometimes, if Anna was home late or Kelly early, they would meet in the little kitchen and make toast together at midnight. Anna would compliment Kelly on her clothes and her hair and her tiny waist and Kelly would laugh and demur and enjoy it all immensely. In the early days of living together Kelly had gone out of her way to compliment Anna in return, but since she found Anna’s way of dressing rather severe all she could find to talk about was books.

‘You must have read so many books. I see those library copies coming and going off the table and I … I can’t imagine.’

And Anna would smile modestly and nod. ‘I’m easily bored.’

‘I’m sure I haven’t read a book since school. I just can’t get through twenty pages without wanting to throw it out the window and do something more fun.’

Anna would shrug and smile. ‘It’s not for everyone.’

Kelly stopped mentioning the books. She stopped commenting on Anna’s cleverness. She smiled and nodded but often her eyes were cold and still. She did not trust Anna – quiet, bookish Anna – and she did not want to be friends with someone she didn’t trust.

Anna was not overly sorry when Kelly withdrew from her attempts at friendship. She had dreaded having to share a flat with someone who would try and drag her out at all hours of the day and night, try to feed her drinks or marijuana and suggest they double-date with this man or that, his friend and his other friend. Men were obstacles to progress, the murderers of time and intellect. Anna did not do men, not in the romantic way at least.

The Turkish cafe two floors below their flat was the same cafe that Anna had waitressed in from the ages of twenty-three to twenty-six. She had, when she first arrived in London, worked as a receptionist in Forest Hill and before that she had lived in Birmingham while she trained as a secretary. Before that had been school somewhere, though no one was ever quite sure where. Anna’s accent was obstinately RP. Ottmar Alabora, the manager of the coffee shop, had always meant to pin Anna down on where exactly it was that she came from, but somehow the moment always eluded him, or he would get her on to the subject and then she’d be called away to service and he didn’t like to seem insistent. He tried not to pay too much attention to any of his waitresses, but particularly not to Anna.

‘We don’t need another waitress,’ his wife Ekin had told him when she caught him, in Anna’s first week, ordering a new uniform from Denny’s.

‘We’re struggling in the evenings. You’re not there. And then I was thinking of putting more tables outside in summer. If you don’t serve people they walk away. Or leave without paying.’

‘But it’s November. Who’s going to sit outside our cafe now?’

‘She’s a nice girl. She’s starting on evenings. You’ll like her. If you don’t like her we’ll let her go.’

So Ekin came and sat in the corner of the restaurant and watched Anna work. She had a nice way with people – Ekin could see that. She was attractive but not in a blousy way. She wore her skirt at the knee and her sleeves below her elbows. Her long hair hung in pigtails and she wore no make-up. When she served Ekin her coffee and cake she smiled and thanked her for the position. Ekin turned to look through the hatch at Ottmar, who raised his eyebrows at her. Ekin made a face, but only to let him know she wasn’t angry. Anna was nice enough; she could stay.

All the same Ottmar carried around a secret shame. He had offered Anna the job in a moment of temporary madness.

She had come in one Tuesday at half past one in her best suit and had ordered coffee – Turkish coffee – which she drank without sugar. She had carried with her a copy of the book she had treated herself to from the basement of a Charing Cross bookshop and Ottmar had read over her shoulder words he loved though hardly knew in English.

‘Oh, come with old Khayyám, and leave the Wise

To talk; one thing is certain, that Life flies;

One thing is certain, and the Rest is Lies;

The Flower that once has blown for ever dies.’

Anna sat quietly, politely, as he read aloud from her book and then she turned and smiled at him and he felt unutterably foolish. He cleared her plate, though he never normally waited on the tables, and then he begged her pardon.

‘I got … I got carried away. Not so many people read poetry.’

‘Even here?’ she asked.

‘In my coffee house?’

‘In London. In Covent Garden. I thought it would have been full of poets.’

‘If it is they are not coming into my coffee house. London is full of …’ Ottmar waved his hands, tipping the spoon from Anna’s saucer. He bent down to retrieve it from under a table then knelt for a moment on the tiled floor. He looked up at Anna and she stared back at him. ‘London is full of … hare-brained people. Chancers. Gamblers. Opium fiends.’ He laughed to himself at his own exaggeration.

‘You make it sound Victorian.’

‘Do I?’

‘Like something out of Conan Doyle.’

‘I don’t—’

‘He wrote Sherlock Holmes.’

‘The Hound of the Baskervilles.’

‘That kind of thing.’

‘My uncle read me Omar Khayyám. In Arabic. Not Turkish or even English. I tried so hard to understand it. I would ask him what it all meant but he always said the pleasure was in the finding out … the discovery. He said you can keep some poems by you your whole life and they will only reveal parts of themselves to you when you are ready to hear them. So at twenty I would understand one little part of it and then at forty something else. I’m probably not making any sense.’

‘Not at all. You’re making lots of sense. I think … I think that would make me impatient. I don’t want to understand poetry when I’m fifty. I want to understand it now. What if I don’t make it to fifty? Do I have to be cheated out of all that understanding?’

Ottmar smiled apologetically. ‘I think perhaps you do. We can only grow old in days and weeks and months. There is not a short cut. Nobody can know the world at fifteen.’

‘When I was at school it used to drive me up the wall listening to the teachers go on about the folly of youth. If someone is ugly you don’t say to them: “Hey you, stop being ugly over there!” so why is it okay to mock the young for being inexperienced?’

‘I was not meaning to mock you, miss!’

‘No! Sorry. I didn’t mean you were. I meant that it sometimes feels hard to be young when no one has a good word to say about youth.’

Ottmar set down her cup and saucer. He frowned at someone out of her line of sight. ‘If we are grumpy it is because we had to leave the party and you are still there.’

‘And the party is a stupid party?’

Ottmar laughed. ‘Yes. A very stupid party. Very loud and drunken and disgusting.’ His eyes crinkled in all directions. ‘But so much fun!’

Anna laughed and Ottmar felt his heart glow in his chest.

‘Will you have anything else, miss? We have cake. We have sweets. We have baklava.’

Anna held her book at arm’s length and glared at it. ‘I spent my lunch money on something else to cheer me up. But your coffee was wonderful.’

‘Why do you need cheering up? Is it a stupid boy?’

‘A stupid boy of fifty.’

‘Too old for you. Forget him.’

‘I was called to interview at Jamiesons on Waldorf Street. And I borrowed five pounds from my landlady to buy this suit because it said: “Professional position. Business attire is requisite.” But when I got there, there were fifteen girls in the waiting room and I had hardly sat down when Mr Jamieson said: “You mustn’t be too disappointed. We had no idea we’d be so popular.” And that was that. With lunch and fares I’m out by six pounds and five shillings and I can’t conjure that kind of money out of the air.’

‘You need a job?’

‘I only have a short-term contract and it’s almost over.’

‘We have a job.’

‘Do you?’

‘Waitressing. It’s not professional, I’m afraid. I’m not sure what you’d do with the suit.’

‘I don’t mind. I mean, I have waitressed before. How many days would you want me?’

‘All week. Six days. You could start this weekend. In the evenings. If that was convenient.’

‘That would be very convenient. My name is Anna. And thank you so much.’

‘I think you should have some baklava to celebrate.’

‘I’m sorry. I’ve nothing left to spend.’

‘It’s on the house,’ said Ottmar expansively. ‘Our waiters eat for free.’

This was not strictly true.

***

Anna caught the bus from Forest Hill to Cambridge Circus every evening at 5 p.m. She worked from 6 p.m. until 11 p.m. and then stayed on until midnight helping to clean up and tidy and sitting around with the other waiters and waitresses playing pontoon for matchsticks and drinking the ends of bottles. Then she walked down to Trafalgar Square and sat for an hour in a shelter on the east side near St Martin-in-the-Fields waiting for a night bus to take her near to home. She became fascinated by the statue of Edith Cavell and would stand at the base of it in the freezing cold of a December morning, looking up.

Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness for anyone.

Sometimes those words made her cry. The tears would come uncontrollably and they would not stop. And in those moments Anna found forgiveness and it made her free. But they were only moments. Forgiveness is a hard thing to hang on to.

The Deplorable Word

Monday, 8 November

Orla Hayes climbed the stairs and pulled on a jumper and another pair of socks. She put her head round the door of Gracie’s little room and pulled the quilt and sheet and blanket up to her chin. She stood for a moment looking down at Gracie’s fat, beautiful face; listening to the sound of the breath that came through lips slightly parted; allowing her hand to brush strands of dark hair away from her closed eyes. Nothing on earth must be allowed to disturb Gracie, for if Gracie was fine then so was all the world.

She left her little one sleeping and crept downstairs to turn off the fire, though it was only ten o’clock and the nights were becoming bitterly cold. Her fingers were tingling now and her nose and the tips of her toes. She had wanted another hour of light and reading or else to darn Gracie’s socks before she went to bed but the cold was going to be too much for her.

She pulled the blue-flowered quilt out of its cubbyhole and made the sofa into a bed, arranging her cushions as she always did. She briefly lit the gas and warmed half a cup of milk, which she mixed with sugar and drank down straight. Then she ran to get warm while the effects of the milk could still be felt and pulled the quilt right up to her eyes. The window in the kitchen whistled and shook in the wind. Brennan was late home tonight and she wanted to be asleep when he came in.

She must have been lying there more than an hour when she heard his keys rattling against the door. Then a click and a scrape of wood and brush against the floor and a gust of cold blew across her face and fingers. The door shut again with a soft crunch.

Brennan Hayes paused for a minute, standing on the mat, listening to the silence in the flat. Then he crept into the kitchen, poured water into a glass, left his boots by the understairs cupboard and softly plodded up towards his bed. Orla listened to him do this just as she had done on hundreds of other nights and she waited for him to speak to her, though this he never did.

The little carriage clock ticked on the windowsill in the darkness. She guessed it was nearly midnight; he was rarely home earlier than half past eleven these days. In six hours Gracie would be awake, sitting on her mother’s stomach, poking her awake and she would grudgingly agree to light the fire again and make them both tea and porridge and the radio would be playing ‘Make It Easy on Yourself’, which always made Orla want to cry. And after seven he would come downstairs, washed and shaved and in his smart, clean uniform and he would drink a cup of tea at the kitchen table while Gracie told him some crazy story about monsters and eyes and tigers walking her to the shops and then he would kiss his daughter on the forehead and say goodbye and he would be out of their lives again for another fifteen hours or months or even years … because in every real sense he had been cut adrift and it was she who had done the cutting.

Tuesday, 9 November

At twenty past seven Brennan Hayes walked out of the house, squeezing the door closed behind him. He could still just feel the warmth of Gracie’s head where he had kissed her. The sky was dark grey and rain spotted his uniform. He turned north onto Finsbury Square and then headed west towards Smithfield Market. Fleet Street. The Strand. Charing Cross Road. Leicester Square. Piccadilly Circus. Savile Row. And at the end of it all – at the end of the road crossings and the grey-suited shuffle and the noise of angry bus drivers and the taste of petrol on his tongue and the spiky cold air of a London morning which thrilled him and froze him in equal measure – at the end of it all lay a different name, a different voice and a different life.

***

‘Excuse me. My name is Anna Treadway. I’ve been called in for an interview at eleven.’

The desk sergeant continued to stare at her sleepily. Anna felt compelled to continue but couldn’t think what else to say.

‘Shall I go and sit over there?’ she asked, nodding to a wooden bench by the door.

The desk sergeant frowned for a moment, as if this was a truly ingenious question to ask. Then he looked her in the eye as if seeing her for the first time: ‘Yes.’

Anna retreated gratefully and sat down, squeezing herself to the very edge of the bench – against the armrest – in case some strange or large or terrifying other should arrive at any moment and be told to sit with her.

Iolanthe had been missing for ten days and Anna could not shake the feeling that not enough was being done to find her. She’d been all over the fronts of the papers for a few days, and posters had appeared on the lamp posts asking for information, and Anna had found herself thinking how ridiculous it all was, and what a waste that Lanny wasn’t here to enjoy all the fuss. But then the boy had been injured in Golden Square, the headlines had changed and she hadn’t seen or heard from a policeman in over a week until the call last night.