Полная версия

Полная версияThe Essays of "George Eliot"

And of God coming to judgment, he says, in the “Night Thoughts:”

“I find my inspiration is my theme;The grandeur of my subject is my muse.”Nothing can be feebler than this “Instalment,” except in the strength of impudence with which the writer professes to scorn the prostitution of fair fame, the “profanation of celestial fire.”

Herbert Croft tells us that Young made more than three thousand pounds by his “Satires” – a surprising statement, taken in connection with the reasonable doubt he throws on the story related in Spence’s “Anecdotes,” that the Duke of Wharton gave Young £2000 for this work. Young, however, seems to have been tolerably fortunate in the pecuniary results of his publications; and, with his literary profits, his annuity from Wharton, his fellowship, and his pension, not to mention other bounties which may be inferred from the high merits he discovers in many men of wealth and position, we may fairly suppose that he now laid the foundation of the considerable fortune he left at his death.

It is probable that the Duke of Wharton’s final departure for the Continent and disgrace at Court in 1726, and the consequent cessation of Young’s reliance on his patronage, tended not only to heighten the temperature of his poetical enthusiasm for Sir Robert Walpole, but also to turn his thoughts toward the Church again, as the second-best means of rising in the world. On the accession of George the Second, Young found the same transcendent merits in him as in his predecessor, and celebrated them in a style of poetry previously unattempted by him – the Pindaric ode, a poetic form which helped him to surpass himself in furious bombast. “Ocean, an Ode: concluding with a Wish,” was the title of this piece. He afterward pruned it, and cut off, among other things, the concluding Wish, expressing the yearning for humble retirement, which, of course, had prompted him to the effusion; but we may judge of the rejected stanzas by the quality of those he has allowed to remain. For example, calling on Britain’s dead mariners to rise and meet their “country’s full-blown glory” in the person of the new King, he says:

“What powerful charm Can Death disarm?Your long, your iron slumbers break? By Jove, by Fame, By George’s name,Awake! awake! awake! awake!”Soon after this notable production, which was written with the ripe folly of forty-seven, Young took orders, and was presently appointed chaplain to the King. “The Brothers,” his third and last tragedy, which was already in rehearsal, he now withdrew from the stage, and sought reputation in a way more accordant with the decorum of his new profession, by turning prose writer. But after publishing “A True Estimate of Human Life,” with a dedication to the Queen, as one of the “most shining representatives” of God on earth, and a sermon, entitled “An Apology for Princes; or, the Reverence due to Government,” preached before the House of Commons, his Pindaric ambition again seized him, and he matched his former ode by another, called “Imperium Pelagi, a Naval Lyric; written in imitation of Pindar’s spirit, occasioned by his Majesty’s return from Hanover, 1729, and the succeeding Peace.” Since he afterward suppressed this second ode, we must suppose that it was rather worse than the first. Next came his two “Epistles to Pope, concerning the Authors of the Age,” remarkable for nothing but the audacity of affectation with which the most servile of poets professes to despise servility.

In 1730 Young was presented by his college with the rectory of Welwyn, in Hertfordshire, and, in the following year, when he was just fifty, he married Lady Elizabeth Lee, a widow with two children, who seems to have been in favor with Queen Caroline, and who probably had an income – two attractions which doubtless enhanced the power of her other charms. Pastoral duties and domesticity probably cured Young of some bad habits; but, unhappily, they did not cure him either of flattery or of fustian. Three more odes followed, quite as bad as those of his bachelorhood, except that in the third he announced the wise resolution of never writing another. It must have been about this time, since Young was now “turned of fifty,” that he wrote the letter to Mrs. Howard (afterward Lady Suffolk), George the Second’s mistress, which proves that he used other engines, besides Pindaric ones, in “besieging Court favor.” The letter is too characteristic to be omitted:

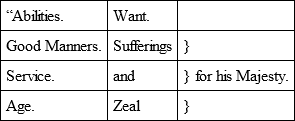

“Monday Morning.“Madam: I know his Majesty’s goodness to his servants, and his love of justice in general, so well, that I am confident, if his Majesty knew my case, I should not have any cause to despair of his gracious favor to me.

These, madam, are the proper points of consideration in the person that humbly hopes his Majesty’s favor.

“As to Abilities, all I can presume to say is, I have done the best I could to improve them.

“As to Good manners, I desire no favor, if any just objection lies against them.

“As for Service, I have been near seven years in his Majesty’s and never omitted any duty in it, which few can say.

“As for Age, I am turned of fifty.

“As for Want, I have no manner of preferment.

“As for Sufferings, I have lost £300 per ann. by being in his Majesty’s service; as I have shown in a Representation which his Majesty has been so good as to read and consider.

“As for Zeal, I have written nothing without showing my duty to their Majesties, and some pieces are dedicated to them.

“This, madam, is the short and true state of my case. They that make their court to the ministers, and not their Majesties, succeed better. If my case deserves some consideration, and you can serve me in it, I humbly hope and believe you will: I shall, therefore, trouble you no farther; but beg leave to subscribe myself, with truest respect and gratitude,

“Yours, etc.,Edward Young.“P.S. I have some hope that my Lord Townshend is my friend; if therefore soon, and before he leaves the court, you had an opportunity of mentioning me, with that favor you have been so good to show, I think it would not fail of success; and, if not, I shall owe you more than any.” – “Suffolk Letters,” vol. i. p. 285.

Young’s wife died in 1741, leaving him one son, born in 1733. That he had attached himself strongly to her two daughters by her former marriage, there is better evidence in the report, mentioned by Mrs. Montagu, of his practical kindness and liberality to the younger, than in his lamentations over the elder as the “Narcissa” of the “Night Thoughts.” “Narcissa” had died in 1735, shortly after marriage to Mr. Temple, the son of Lord Palmerston; and Mr. Temple himself, after a second marriage, died in 1740, a year before Lady Elizabeth Young. These, then, are the three deaths supposed to have inspired “The Complaint,” which forms the three first books of the “Night Thoughts:”

“Insatiate archer, could not one suffice?Thy shaft flew thrice: and thrice my peace was slain:And thrice, ere thrice yon moon had fill’d her horn.”Since we find Young departing from the truth of dates, in order to heighten the effect of his calamity, or at least of his climax, we need not be surprised that he allowed his imagination great freedom in other matters besides chronology, and that the character of “Philander” can, by no process, be made to fit Mr. Temple. The supposition that the much-lectured “Lorenzo” of the “Night Thoughts” was Young’s own son is hardly rendered more absurd by the fact that the poem was written when that son was a boy, than by the obvious artificiality of the characters Young introduces as targets for his arguments and rebukes. Among all the trivial efforts of conjectured criticism, there can hardly be one more futile than the attempts to discover the original of those pitiable lay-figures, the “Lorenzos” and “Altamonts” of Young’s didactic prose and poetry. His muse never stood face to face with a genuine living human being; she would have been as much startled by such an encounter as a necromancer whose incantations and blue fire had actually conjured up a demon.

The “Night Thoughts” appeared between 1741 and 1745. Although he declares in them that he has chosen God for his “patron” henceforth, this is not at all to the prejudice of some half dozen lords, duchesses, and right honorables who have the privilege of sharing finely-turned compliments with their co-patron. The line which closed the Second Night in the earlier editions —

“Wits spare not Heaven, O Wilmington! – nor thee” —

is an intense specimen of that perilous juxtaposition of ideas by which Young, in his incessant search after point and novelty, unconsciously converts his compliments into sarcasms; and his apostrophe to the moon as more likely to be favorable to his song if he calls her “fair Portland of the skies,” is worthy even of his Pindaric ravings. His ostentatious renunciation of worldly schemes, and especially of his twenty-years’ siege of Court favor, are in the tone of one who retains some hope in the midst of his querulousness.

He descended from the astronomical rhapsodies of his “Ninth Night,” published in 1745, to more terrestrial strains in his “Reflections on the Public Situation of the Kingdom,” dedicated to the Duke of Newcastle; but in this critical year we get a glimpse of him through a more prosaic and less refracting medium. He spent a part of the year at Tunbridge Wells; and Mrs. Montagu, who was there too, gives a very lively picture of the “divine Doctor” in her letters to the Duchess of Portland, on whom Young had bestowed the superlative bombast to which we have recently alluded. We shall borrow the quotations from Dr. Doran, in spite of their length, because, to our mind, they present the most agreeable portrait we possess of Young:

“I have great joy in Dr. Young, whom I disturbed in a reverie. At first he started, then bowed, then fell back into a surprise; then began a speech, relapsed into his astonishment two or three times, forgot what he had been saying; began a new subject, and so went on. I told him your grace desired he would write longer letters; to which he cried ‘Ha!’ most emphatically, and I leave you to interpret what it meant. He has made a friendship with one person here, whom I believe you would not imagine to have been made for his bosom friend. You would, perhaps, suppose it was a bishop or dean, a prebend, a pious preacher, a clergyman of exemplary life, or, if a layman, of most virtuous conversation, one that had paraphrased St. Matthew, or wrote comments on St. Paul… You would not guess that this associate of the doctor’s was – old Cibber! Certainly, in their religious, moral, and civil character, there is no relation; but in their dramatic capacity there is some. – Mrs. Montagu was not aware that Cibber, whom Young had named not disparagingly in his Satires, was the brother of his old school-fellow; but to return to our hero. ‘The waters,’ says Mrs. Montagu, ‘have raised his spirits to a fine pitch, as your grace will imagine, when I tell you how sublime an answer he made to a very vulgar question. I asked him how long he stayed at the Wells; he said, ‘As long as my rival stayed; – as long as the sun did.’ Among the visitors at the Wells were Lady Sunderland (wife of Sir Robert Sutton), and her sister, Mrs. Tichborne. ‘He did an admirable thing to Lady Sunderland: on her mentioning Sir Robert Sutton, he asked her where Sir Robert’s lady was; on which we all laughed very heartily, and I brought him off, half ashamed, to my lodgings, where, during breakfast, he assured me he had asked after Lady Sunderland, because he had a great honor for her; and that, having a respect for her sister, he designed to have inquired after her, if we had not put it out of his head by laughing at him. You must know, Mrs. Tichborne sat next to Lady Sunderland. It would have been admirable to have had him finish his compliment in that manner.’.. ‘His expressions all bear the stamp of novelty, and his thoughts of sterling sense. He practises a kind of philosophical abstinence… He carried Mrs. Rolt and myself to Tunbridge, five miles from hence, where we were to see some fine old ruins. First rode the doctor on a tall steed, decently caparisoned in dark gray; next, ambled Mrs. Rolt on a hackney horse;.. then followed your humble servant on a milk-white palfrey. I rode on in safety, and at leisure to observe the company, especially the two figures that brought up the rear. The first was my servant, valiantly armed with two uncharged pistols; the last was the doctor’s man, whose uncombed hair so resembled the mane of the horse he rode, one could not help imagining they were of kin, and wishing, for the honor of the family, that they had had one comb betwixt them. On his head was a velvet cap, much resembling a black saucepan, and on his side hung a little basket. At last we arrived at the King’s Head, where the loyalty of the doctor induced him to alight; and then, knight-errant-like, he took his damsels from off their palfreys, and courteously handed us into the inn.’.. The party returned to the Wells; and ‘the silver Cynthia held up her lamp in the heavens’ the while. ‘The night silenced all but our divine doctor, who sometimes uttered things fit to be spoken in a season when all nature seems to be hushed and hearkening. I followed, gathering wisdom as I went, till I found, by my horse’s stumbling, that I was in a bad road, and that the blind was leading the blind. So I placed my servant between the doctor and myself; which he not perceiving, went on in a most philosophical strain, to the great admiration of my poor clown of a servant, who, not being wrought up to any pitch of enthusiasm, nor making any answer to all the fine things he heard, the doctor, wondering I was dumb, and grieving I was so stupid, looked round and declared his surprise.’”

Young’s oddity and absence of mind are gathered from other sources besides these stories of Mrs. Montagu’s, and gave rise to the report that he was the original of Fielding’s “Parson Adams;” but this Croft denies, and mentions another Young, who really sat for the portrait, and who, we imagine, had both more Greek and more genuine simplicity than the poet. His love of chatting with Colley Cibber was an indication that the old predilection for the stage survived, in spite of his emphatic contempt for “all joys but joys that never can expire;” and the production of “The Brothers,” at Drury Lane in 1753, after a suppression of fifteen years, was perhaps not entirely due to the expressed desire to give the proceeds to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. The author’s profits were not more than £400 – in those days a disappointing sum; and Young, as we learn from his friend Richardson, did not make this the limit of his donation, but gave a thousand guineas to the Society. “I had some talk with him,” says Richardson, in one of his letters, “about this great action. ‘I always,’ said he, ‘intended to do something handsome for the Society. Had I deferred it to my demise, I should have given away my son’s money. All the world are inclined to pleasure; could I have given myself a greater by disposing of the sum to a different use, I should have done it.’” Surely he took his old friend Richardson for “Lorenzo!”

His next work was “The Centaur not Fabulous; in Six Letters to a Friend, on the Life in Vogue,” which reads very much like the most objurgatory parts of the “Night Thoughts” reduced to prose. It is preceded by a preface which, though addressed to a lady, is in its denunciations of vice as grossly indecent and almost as flippant as the epilogues written by “friends,” which he allowed to be reprinted after his tragedies in the latest edition of his works. We like much better than “The Centaur,” “Conjectures on Original Composition,” written in 1759, for the sake, he says, of communicating to the world the well-known anecdote about Addison’s deathbed, and with the exception of his poem on Resignation, the last thing he ever published.

The estrangement from his son, which must have embittered the later years of his life, appears to have begun not many years after the mother’s death. On the marriage of her second daughter, who had previously presided over Young’s household, a Mrs. Hallows, understood to be a woman of discreet age, and the daughter (a widow) of a clergyman who was an old friend of Young’s, became housekeeper at Welwyn. Opinions about ladies are apt to differ. “Mrs. Hallows was a woman of piety, improved by reading,” says one witness. “She was a very coarse woman,” says Dr. Johnson; and we shall presently find some indirect evidence that her temper was perhaps not quite so much improved as her piety. Servants, it seems, were not fond of remaining long in the house with her; a satirical curate, named Kidgell, hints at “drops of juniper” taken as a cordial (but perhaps he was spiteful, and a teetotaller); and Young’s son is said to have told his father that “an old man should not resign himself to the management of anybody.” The result was, that the son was banished from home for the rest of his father’s life-time, though Young seems never to have thought of disinheriting him.

Our latest glimpses of the aged poet are derived from certain letters of Mr. Jones, his curate – letters preserved in the British Museum, and happily made accessible to common mortals in Nichols’s “Anecdotes.” Mr. Jones was a man of some literary activity and ambition – a collector of interesting documents, and one of those concerned in the “Free and Candid Disquisitions,” the design of which was “to point out such things in our ecclesiastical establishment as want to be reviewed and amended.” On these and kindred subjects he corresponded with Dr. Birch, occasionally troubling him with queries and manuscripts. We have a respect for Mr. Jones. Unlike any person who ever troubled us with queries or manuscripts, he mitigates the infliction by such gifts as “a fat pullet,” wishing he “had anything better to send; but this depauperizing vicarage (of Alconbury) too often checks the freedom and forwardness of my mind.” Another day comes a “pound canister of tea,” another, a “young fatted goose.” Clearly, Mr. Jones was entirely unlike your literary correspondents of the present day; he forwarded manuscripts, but he had “bowels,” and forwarded poultry too. His first letter from Welwyn is dated June, 1759, not quite six years before Young’s death. In June, 1762, he expresses a wish to go to London “this summer. But,” he continues:

“My time and pains are almost continually taken up here, and.. I have been (I now find) a considerable loser, upon the whole, by continuing here so long. The consideration of this, and the inconveniences I sustained, and do still experience, from my late illness, obliged me at last to acquaint the Doctor (Young) with my case, and to assure him that I plainly perceived the duty and confinement here to be too much for me; for which reason I must (I said) beg to be at liberty to resign my charge at Michaelmas. I began to give him these notices in February, when I was very ill; and now I perceive, by what he told me the other day, that he is in some difficulty: for which reason he is at last (he says) resolved to advertise, and even (which is much wondered at) to raise the salary considerably higher. (What he allowed my predecessors was 20l. per annum; and now he proposes 50l., as he tells me.) I never asked him to raise it for me, though I well knew it was not equal to the duty; nor did I say a word about myself when he lately suggested to me his intentions upon this subject.”

In a postscript to this letter he says:

“I may mention to you farther, as a friend that may be trusted, that in all likelihood the poor old gentleman will not find it a very easy matter, unless by dint of money, and force upon himself, to procure a man that he can like for his next curate, nor one that will stay with him so long as I have done. Then, his great age will recur to people’s thoughts; and if he has any foibles, either in temper or conduct, they will be sure not to be forgotten on this occasion by those who know him; and those who do not will probably be on their guard. On these and the like considerations, it is by no means an eligible office to be seeking out for a curate for him, as he has several times wished me to do; and would, if he knew that I am now writing to you, wish your assistance also. But my best friends here, who well foresee the probable consequences, and wish me well, earnestly dissuade me from complying: and I will decline the office with as much decency as I can: but high salary will, I suppose, fetch in somebody or other, soon.”

In the following July he writes:

“The old gentleman here (I may venture to tell you freely) seems to me to be in a pretty odd way of late – moping, dejected, self-willed, and as if surrounded with some perplexing circumstances. Though I visit him pretty frequently for short intervals, I say very little to his affairs, not choosing to be a party concerned, especially in cases of so critical and tender a nature. There is much mystery in almost all his temporal affairs, as well as in many of his speculative theories. Whoever lives in this neighborhood to see his exit will probably see and hear some very strange things. Time will show; – I am afraid, not greatly to his credit. There is thought to be an irremovable obstruction to his happiness within his walls, as well as another without them; but the former is the more powerful, and like to continue so. He has this day been trying anew to engage me to stay with him. No lucrative views can tempt me to sacrifice my liberty or my health, to such measures as are proposed here. Nor do I like to have to do with persons whose word and honor cannot be depended on. So much for this very odd and unhappy topic.”

In August Mr. Jones’s tone is slightly modified. Earnest entreaties, not lucrative considerations, have induced him to cheer the Doctor’s dejected heart by remaining at Welwyn some time longer. The Doctor is, “in various respects, a very unhappy man,” and few know so much of these respects as Mr. Jones. In September he recurs to the subject:

“My ancient gentleman here is still full of trouble, which moves my concern, though it moves only the secret laughter of many, and some untoward surmises in disfavor of him and his household. The loss of a very large sum of money (about 200l.) is talked of; whereof this vill and neighborhood is full. Some disbelieve; others says, ‘It is no wonder, where about eighteen or more servants are sometimes taken and dismissed in the course of a year.’ The gentleman himself is allowed by all to be far more harmless and easy in his family than some one else who hath too much the lead in it. This, among others, was one reason for my late motion to quit.”

No other mention of Young’s affairs occurs until April 2d, 1765, when he says that Dr. Young is very ill, attended by two physicians.

“Having mentioned this young gentleman (Dr. Young’s son), I would acquaint you next, that he came hither this morning, having been sent for, as I am told, by the direction of Mrs. Hallows. Indeed, she intimated to me as much herself. And if this be so, I must say, that it is one of the most prudent Acts she ever did, or could have done in such a case as this; as it may prove a means of preventing much confusion after the death of the Doctor. I have had some little discourse with the son: he seems much affected, and I believe really is so. He earnestly wishes his father might be pleased to ask after him; for you must know he has not yet done this, nor is, in my opinion, like to do it. And it has been said farther, that upon a late application made to him on the behalf of his son, he desired that no more might be said to him about it. How true this may be I cannot as yet be certain; all I shall say is, it seems not improbable.. I heartily wish the ancient man’s heart may prove tender toward his son; though, knowing him so well, I can scarce hope to hear such desirable news.”

Eleven days later he writes:

“I have now the pleasure to acquaint you, that the late Dr. Young, though he had for many years kept his son at a distance from him, yet has now at last left him all his possessions, after the payment of certain legacies; so that the young gentleman (who bears a fair character, and behaves well, as far as I can hear or see) will, I hope, soon enjoy and make a prudent use of a handsome fortune. The father, on his deathbed, and since my return from London, was applied to in the tenderest manner, by one of his physicians, and by another person, to admit the son into his presence, to make submission, intreat forgiveness, and obtain his blessing. As to an interview with his son, he intimated that he chose to decline it, as his spirits were then low and his nerves weak. With regard to the next particular, he said, ‘I heartily forgive him;’ and upon ‘mention of this last, he gently lifted up his hand, and letting it gently fall, pronounced these words, ‘God bless him!’.. I know it will give you pleasure to be farther informed that he was pleased to make respectful mention of me in his will; expressing his satisfaction in my care of his parish, bequeathing to me a handsome legacy, and appointing me to be one of his executors.”