Полная версия

Полная версияAn Englishman's View of the Battle between the Alabama and the Kearsarge

Frederick Milnes Edge

An Englishman's View of the Battle between the Alabama and the Kearsarge / An Account of the Naval Engagement in the British Channel, on Sunday June 19th, 1864

The Alabama and the Kearsarge

The importance of the engagement between the United States Sloop-of-war, Kearsarge, and the Confederate Privateer, Alabama, cannot be estimated by the size of the two vessels. The conflict off Cherbourg on Sunday, the 19th of June, was the first decisive engagement between shipping propelled by steam, and the first test of the merits of modern naval artillery. It was, moreover, a contest for superiority between the ordnance of Europe and America, whilst the result furnishes us with data wherefrom to estimate the relative advantages of rifled and smooth-bore cannon at short range.

Perhaps no greater or more numerous misrepresentations were ever made in regard to an engagement than in reference to the one in question. The first news of the conflict came to us enveloped in a mass of statements, the greater part of which, not to use an unparliamentary expression, was diametrically opposed to the truth; and although several weeks have now elapsed since the Alabama followed her many defenceless victims to their watery grave, these misrepresentations obtain as much credence as ever. The victory of the Kearsarge was accounted for, and the defeat of the Alabama excused or palliated upon the following principal reasons: —

1. The superior size and speed of the Kearsarge.

2. The superiority of her armament.

3. The chain-plating at her sides.

4. The greater number of her crew.

5. The unpreparedness of the Alabama.

6. The assumed necessity of Captain Semmes’ accepting the challenge sent him (as represented) by the commander of the Kearsarge.

Besides these misstatements there have been others put forth, either in ignorance of the real facts of the case, or with a purposed intention of diminishing the merit of the victory by casting odium upon the Federals on the score of inhumanity. In the former category must be placed the remarks of the Times (June 21st); but it is just to state that the observations in question were made on receipt of the first news, and from information furnished probably by parties unconnected with the paper, and desirous of palliating the Alabama’s defeat by any means in their power. We are informed in the article above referred to that the guns of the latter vessel “had been pointed for 2,000 yards, and the second shot went right through the Kearsarge,” whereas no shot whatever went through as stated. Again, “the Kearsarge fired about 100 (shot) chiefly 11-in. shell,” the fact being that not one-third of her projectiles were of that calibre. Further on we find – “The men (of the Alabama) were all true to the last; they only ceased firing when the water came to the muzzles of their guns.” Such a declaration as this is laughable in the extreme; the Alabama’s guns were all on the spar-deck, like those of the Kearsarge; and, to achieve what the Times represents, her men must have fought on until the hull of their vessel was two feet under water. The truth is – if the evidence of the prisoners saved by the Kearsarge may be taken – Captain Semmes hauled down his flag immediately after being informed by his chief engineer that the water was putting out the fires; and, within a few minutes, the water gained so rapidly on the vessel that her bow rose slowly in the air, and half her guns obtained a greater elevation than they had ever known previously. It is unfortunate to find such cheap-novel style of writing in a paper which at some future period may be referred to as an authoritative chronicler of events now transpiring.

It would be too long a task to notice all the numerous misstatements of private individuals, and of the English and French press in reference to this action: the best mode is to give the facts as they occurred, leaving the public to judge by internal evidence on which side the truth exists.

Within a few days of the fight, the writer of these pages crossed from London to Cherbourg for the purpose of obtaining by personal examination full and precise information in reference to the engagement. It would seem as though misrepresentation, if not positive falsehood, were inseparable from everything connected with the Alabama, for on reaching the French naval station he was positively assured by the people on shore that nobody was permitted to board the Kearsarge. Preferring, however, to substantiate the truth of these allegations, from the officers of the vessel themselves, he hired a boat and sailed out to the sloop, receiving on his arrival an immediate and polite reception from Captain Winslow and his gallant subordinates. During the six days he remained at Cherbourg, he found the Kearsarge open to the inspection, above and below, of any and everybody who chose to visit her; and he frequently heard surprise expressed by English and French visitors alike that representations on shore were so inconsonant with the truth of the case.

I found the Kearsarge lying under the guns of the French ship-of-the-line “Napoleon,” two cables’ length from that vessel, and about a mile and a half from the harbour; she had not moved from that anchorage since entering the port of Cherbourg, and no repairs whatever had been effected in her hull since the fight. I had thus full opportunity to examine the extent of her damage, and she certainly did not look at all like a vessel which had just been engaged in one of the hottest conflicts of modern times.

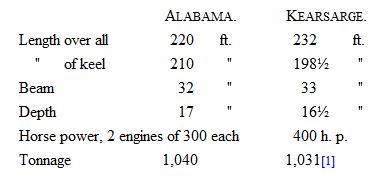

SIZE OF THE TWO VESSELS.

The Kearsarge, in size, is by no means the terrible craft represented by those who, for some reason or other, seek to detract from the honour of her victory; she appeared to me a mere yacht in comparison with the shipping around her, and disappointed many of the visitors who came to see her. The relative proportions of the two antagonists were as follows: —

1The Kearsarge has a four-bladed screw, diameter 12-ft 9-in. with a pitch of 20-ft.

The Alabama was a barque-rigged screw propeller, and the heaviness of her rig, and, above all, the greater size and height of her masts would give her the appearance of a much larger vessel than her antagonist. The masts of the latter are disproportionately low and small; she has never carried more than top-sail yards, and depends for her speed upon her machinery alone. It is to be questioned whether the Alabama, with all her reputation for velocity, could, in her best trim, outsteam her rival. The log book of the Kearsarge, which I was courteously permitted to examine, frequently shows a speed of upwards of fourteen knots the hour, and her engineers state that her machinery was never in better working order than at the present time. I have not seen engines more compact in form, nor, apparently, in finer condition; looking in every part as though they were fresh from the workshop, instead of being, as they, are, half through the third year of the cruise.

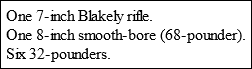

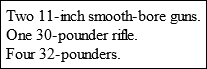

Ships-of-war, however, whatever may be their tonnage, are nothing more than platforms for carrying artillery. The only mode by which to judge of the strength of the two vessels is in comparing their armaments; and herein we find the equality of the antagonist as fully exemplified as in the respective proportions of their hulls and steam-power. The armaments of the Alabama and Kearsarge were are as follows:

ARMAMENT OF THE ALABAMA.

ARMAMENT OF THE KEARSARGE.

It will therefore be seen that the Alabama had the advantage of the Kearsarge – at all events in the number of her guns; whilst the weight of the latter’s broadside was only some 20 per cent. greater than her own. This disparity, however, was more than made up by the greater rapidity of the Alabama’s firing, and, above all, by the superiority of her artillerymen. The Times informs us that Capt. Semmes asserts, “he owes his best men to the training they received on board the ‘Excellent;’” and trained gunners must naturally be superior to the volunteer gunners on board the Kearsarge. Each vessel fought all her guns, with the exception in either case of one 32-pounder, on the starboard side; but the struggle was really decided by the two 11-inch Dahlgren smooth-bores of the Kearsarge against the 7-inch Blakely rifle and the heavy 68-pounder pivot of the Alabama. The Kearsarge certainly carried a small 30-pounder rifled Dahlgren in pivot on her forecastle, and this gun was fired several times before the rest were brought into play; but the gun in question was never regarded as aught than a failure, and the Ordnance Department of the United States’ Navy has given up its manufacture.

THE CHAIN-PLATING OF THE KEARSARGEGreat stress has been laid upon the chain-plating of the Kearsarge, and it is assumed by interested parties that, but for this armour, the contest would have resulted differently. A pamphlet lately published in this city, entitled “The Career of the Alabama,”1 makes the following statements:

“The Federal Government had fitted out the Kearsarge, a new vessel of great speed, iron-coated,” &c. (p. 23).

“She,” the Kearsarge, “appeared to be temporarily plated with iron chains.” (p. 38.) (In the previous quotation, it would appear she had so been plated by the Federal Government: both statements are absolutely incorrect, as will shortly be seen.)

“It was frequently observed that shot and shell struck against the Kearsarge’s side, and harmlessly rebounded, bursting outside, and doing no damage to the Federal crew.”

“Another advantage accruing from this was that it sank her very low in the water, so low in fact, that the heads of the men who were in the boats were on the level of the Kearsarge’s deck.” (p. 39.)

“As before observed, the sides of the Kearsarge were trailed all over with chain cables.” (p. 41).

The author of the pamphlet in question has judiciously refrained from giving his name. A greater number of more unblushing misrepresentations never were contained in an equal space.

In his official report to the Confederate Envoy, Mr. Mason, Captain Semmes makes the following statements:

“At the end of the engagement, it was discovered by those of our officers who went alongside the enemy’s ship with the wounded, that her midship section on both sides was thoroughly iron-coated; this having been done with chain constructed for the purpose, (!) placed perpendicularly from the rail to the water’s edge, the whole covered over by a thin outer planking, which gave no indication of the armour beneath. This planking had been ripped off in every direction (!) by our shot and shell, the chain broken and indented in many places, and forced partly into the ship’s side. She was most effectually guarded, however, in this section from penetration.”

“The enemy was heavier than myself, both in ship, battery, and crew, (!) but I did not know until the action was over that she was also iron-clad.”

“Those of our officers who went alongside the enemy’s ship with our wounded.” As soon as Captain Semmes reached the Deerhound, the yacht steamed off at full speed towards Southampton, and Semmes wrote his report of the fight either in England, or on board the English vessel. Probably the former, for he dates his communication to Mr. Mason – “Southampton, June 21, 1864.” How did he obtain intelligence from those of his officers “who went alongside the enemy’s ship,” and who would naturally be detained as prisoners of war? It was impossible for anybody to reach Southampton in the time specified; nevertheless he did obtain such information. One of his officers – George T. Fullam, an Englishman unfortunately – came to the Kearsarge in a boat at the close of the action, representing the Alabama to be sinking, and that if the Kearsarge did not hasten to get out boats to save life, the crew must go down with her. Not a moment was to be lost, and he offered to go back to his own vessel to bring off prisoners, pledging his honour to return when the object was accomplished. After picking up several men struggling in the water, he steered directly for the Deerhound, and on reaching her actually cast his boat adrift. It was subsequently picked up by the Kearsarge. Fullam’s name appears amongst the list of “saved” by the Deerhound; and he, with others of the Alabama’s officers who had received a similar permission from their captors, and had similarly broken their troth, of course gave the above information to their veracious Captain.

The chain-plating of the Kearsarge was decided upon in this wise. The vessel lay off Fayal towards the latter part of April, 1863, on the look out for a notorious blockade-runner, named the “Juno.” The Kearsarge being short of coal, and, fearing some attempts at opposition on the part of her prey, the first officer of the sloop, Lieutenant-commander James S. Thornton, suggested to Captain Winslow the advisability of hanging her two sheet-anchor cables over her sides, so as to protect her midship section. Mr. Thornton had served on board the flag-ship of Admiral Farragut, the “Hartford” when she and the rest of the Federal fleet ran the forts of the Mississippi to reach New Orleans; and he made the suggestion at Fayal through having seen the advantage gained by it on that occasion. I now copy the following extract from the log-book of the Kearsarge:

“Horta Bay, Fayal (May 1st, 1863.)“From 8 to Merid. Wind E.N.E. (F 2). Weather b. c. Strapped, loaded, and fused (5 sec. fuse) 13 XI-inch shell. Commenced armour plating ship, using sheet chain. Weighed kedge anchor.

“(Signed) E. M.Stoddard, Acting Master.”

This operation of chain-armouring took three days, and was effected without assistance from the shore and at an expense of material of seventy-five dollars (£15). In order to make the addition less unsightly, the chains were boxed over with ¾-inch deal boards, forming a case, or box, which stood out at right angles from the vessel’s sides. This box would naturally excite curiosity in every port where the Kearsarge touched, and no mystery was made as to what the boarding covered. Captain Semmes was perfectly cognizant of the entire affair, notwithstanding his shameless assertion of ignorance; for he spoke about it to his officers and crew several days prior to the 19th of June, declaring that the chains were only attached together with rope-yarns, and would drop into the water when struck with the first shot. I was so informed by his own wounded men lying in the naval hospital at Cherbourg. Whatever might be the value for defence of this chain-plating, it was only struck once during the engagement, so far as I could discover by a long and close inspection. Some of the officers of the Kearsarge asserted to me that it was struck twice, whilst others deny that declaration: in one spot, however, a 32-pounder shot broke in the deal covering and smashed a single link, two-thirds of which fell into the water. The remainder is in my possession, and proves to be of the ordinary 5¼-inch chain. Had the cable been struck by the rifled 120-pounder instead of by a 32, the result might have been different; but in any case the damage would have amounted to nothing serious, for the vessel’s side was hit five feet above the water-line and nowhere in the vicinity of the boilers or machinery. Captain Semmes evidently regarded this protection of the chains as little worth, for he might have adopted the same plan before engaging the Kearsarge; but he confined himself to taking on board 150 tons of coal as a protection to his boilers, which, in addition to the 200 tons already in his bunkers, would bring him pretty low in the water. The Kearsarge, on the contrary, was deficient in her coal, and she took what was necessary on board during my stay at Cherbourg.

The quantity of chain used on each side of the vessel in this much-talked-of armouring is only 120 fathoms, and it covers a space amidships of 49 ft. 6 in. in length, by 6 ft. 2 in. in depth.2 The chain, which is single, not double, was and is stopped to eye-bolts with rope-yarn and by iron dogs.3 Is it reasonable to suppose that this plating of 17⁄10-inch iron (the thickness of the links of the chain) could offer any serious resistance to the heavy 68-pounder and the 7 in. Blakely rifle of the Alabama – at the comparatively close range of 700 yards? What then becomes of the mistaken remark of the Times that the Kearsarge was “provided, as it turned out, with some special contrivances for protection,” or Semmes’ declaration that she was “iron-clad?” “The Career of the Alabama,” in referring to this chain-plating, says – “Another advantage accruing from this was that it sank her very low in the water, so low in fact, that the heads of the men who were in the boats were on the level of the Kearsarge’s deck.” It is simply ridiculous to suppose that the weight of 240 fathoms of chain could have any such effect upon a vessel of one thousand tons burden; whilst, in addition, the cable itself was part of the ordinary equipment of the ship. Further, the supply of coal on board the Kearsarge at the time of action was only 120 tons, while the Alabama had 350 tons on board.

The objection that the Alabama was short-handed does not appear to be borne out by the facts of the case; while, on the other hand, a greater number of men than were necessary to work the guns and ship would be more of a detriment than a benefit to the Kearsarge. The latter vessel had 22 officers on board, and 140 men: the Alabama is represented to have had only 120 in her crew, (Mr. Mason’s statement,) but if her officers be included in this number, the assertion is obviously incorrect, for the Kearsarge saved 67,4 the Deerhound 41, and the French pilot-boats 12, and this, without mentioning the 13 accounted for as killed and wounded,5 and others who went down with the ship. When the Alabama arrived at Cherbourg, her officers and crew numbered 149. This information was given by captains of American vessels who were held as prisoners on board the privateer after the destruction of their ships; and their information is indorsed by the captured officers of the Alabama now on board the Kearsarge. It is known also that many persons tried to get on board the Alabama while she lay in Cherbourg; but this the police prevented as far as lay in their power. If Captain Semmes’ representation were correct in regard to his being short-handed, he certainly ought not to be trusted with the command of a vessel again, however much he may be esteemed by some parties for his Quixotism in challenging an antagonist – to use his own words – “heavier than myself both in ship, battery, and crew.”

The asserted unpreparedness of the Alabama is about as truthful as the other representations, if we may take Captain Semmes’ report, and certain facts, in rebutting evidence. The Captain writes to Mr. Mason, “I cannot deny myself the pleasure of saying that Mr. Kell, my First Lieutenant, deserves great credit for the fine condition the ship was in when she went into action;” but if Captain Semmes were right in the alleged want of preparation, he himself is alone to blame. He had ample time for protecting his vessel and crew in all possible manners; he, not the Kearsarge was the aggressor; and but for his forcing the fight, the Alabama might still be riding inside Cherbourg breakwater. Notwithstanding the horrible cause for which he is struggling, and the atrocious depredations he has committed upon helpless merchantmen, we can still admire the daring he evinced in sallying forth from a secure haven and gallantly attacking his opponent; but when he professes ignorance of the character of his antagonist, and unworthily attempts to disparage the victory of his foe, we forget all our first sympathies, and condemn the moral nature of the man, as he has forced us to do his judgment.

Nor must it be forgotten that the Kearsarge has had fewer opportunities for repairs than the Alabama, and that she has been cruising around in all seas for a much longer period than her antagonist.6 The Alabama, on the contrary, had lain for many days in Cherbourg, and she only steamed forth when her Captain supposed her to be in, at all events, as good a condition as the enemy.

THE CHALLENGEFinally, the challenge to fight was given by the Alabama to the Kearsarge, not by the Kearsarge to the Alabama. “The Career of the Alabama,” above referred to makes the following romantic statement:

“When he (Semmes) was challenged by the commander of the Kearsarge, everybody in Cherbourg, it appears, said it would be disgraceful if he refused the challenge, and this, coupled with his belief that the Kearsarge was not so strong as she really proved to be, made him agree to fight.” (p. 41.)

On the Tuesday after the battle, and before leaving London for Cherbourg, I was shown a telegram by a member of the House of Commons, forwarded to him that morning. The telegram was addressed to one of the gentleman’s constituents by his son, a sailor on board the Alabama, and was dated “C. S. S. Alabama, Cherbourg, June 14th,” the sender stating that they were about to engage the Kearsarge on the morrow, or next day. I have not a copy of this telegram, but “The Career of the Alabama” gives a letter to the like effect from the surgeon of the privateer, addressed to a gentleman of this city. The letter reads as follows:

“Cherbourg, June 14, 1864.Dear Travers – Here we are. I send this by a gentleman coming to London. An enemy is outside. If she only stays long enough, we go out and fight her. If I live, expect to see me in London shortly. If I die, give my best love to all who know me. If Monsieur A. de Caillet should call on you, please show him every attention.

“I remain, dear Travers, ever yours,“D. H. Llewellyn.”There were two brave gentlemen on board the Alabama – poor Llewellyn, who nobly refused to save his own life, by leaving his wounded, and a young Lieutenant, Mr. Joseph Wilson, who honourably delivered up his sword on the deck of the Kearsarge, when the other officers threw theirs into the water.

The most unanswerable proof of Captain Semmes having challenged the commander of the Kearsarge is to be found in the following letter addressed by him to the Confederate consul, or agent, at Cherbourg. After the publication of this document, it is to be hoped we shall hear no more of Captain Winslow’s having committed such a breach of discipline and etiquette as that of challenging a rebel against his Government.

CAPTAIN SEMMES’ CHALLENGE TO THE KEARSARGE“C. S. S. Alabama,“Cherbourg, June 14, 1864.“To Ad. Bonfils, Cherbourg:

“Sir – I hear that you were informed by the U. S. Consul, that the Kearsarge was to come to this port solely for the prisoners landed by me,7 and that she was to depart in twenty-four hours. I desire you to say to the U. S. Consul, that my intention is to fight the Kearsarge as soon as I can make the necessary arrangements. I hope these will not detain me more than until tomorrow evening, or after the morrow morning at farthest. I beg she will not depart before I am ready to go out.

“I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

“R. Semmes, Captain.”Numerous facts serve to prove that Captain Semmes had made every preparation to engage the Kearsarge, and that wide-spread publicity had been given to his intention. As soon as the arrival of the Federal vessel was known at Paris, an American gentleman of high position came down to Cherbourg, with instructions for Captain Winslow; but so desirous were the French authorities to preserve a really honest neutrality, that permission was only granted to him to sail to her after his promise to return to shore immediately on the delivery of his message. Once back in Cherbourg, and about to return to Paris, he was advised to remain over night, as the Alabama intended to fight the Kearsarge next day (Sunday). On Sunday morning, an excursion train arrived from the Capital, and the visitors were received at the terminus of the railway by the boatmen of the port, who offered them boats for the purpose of seeing a genuine naval battle which was to take place during the day. Turning such a memorable occurrence to practical uses, Monsieur Rondin, a celebrated photographic artist on the Place d’Armes at Cherbourg, prepared the necessary chemicals, plates, and camera, and placed himself on the summit of the old church tower which the whilome denizens of Cherbourg had very properly built in happy juxtaposition with his establishment. I was only able to see the negative, but that was quite sufficient to show that the artist had obtained a very fine view indeed of the exciting contest. Five days, however, had elapsed since Captain Semmes sent his challenge to Captain Winslow through the Confederate agent, Monsieur Bonfils; surely time sufficient for him to make all the preparations which he considered necessary. Meanwhile the Kearsarge was cruising to and fro at sea, outside the breakwater.