Полная версия:

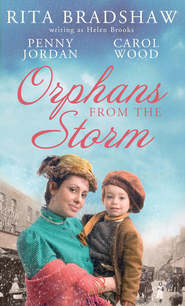

Orphans from the Storm: Bride at Bellfield Mill / A Family for Hawthorn Farm / Tilly of Tap House

‘Yes, do come in Mr Gledhill.’ Marianne smiled politely at him. ‘I am Mr Denshaw’s new housekeeper, Mrs Brown.’

‘Yes, I ’eard as to how you was ’ere. And lucky for t’master that you are an’ all,’ he told her, glancing approvingly round the pin-neat kitchen. His approval turned to a frown, though, when he saw the nurse. ‘You’ll not be letting ’er anywhere near t’master?’ he asked Marianne sharply.

‘Dr Hollingshead sent her up,’ Marianne told him.

‘T’master won’t want her ’ere. Not after what happened to his missus and babby. If you’ll take my advice you’ll send her about her business.’

‘If you think I should.’

‘I do,’ he assured her grimly.

Marianne nodded her head. His words had only confirmed her own fears about the nurse’s suitability for her work.

‘I’ll go and inform Mr Denshaw that you’re here. If you would like a cup of tea…?’

‘That’s right kind of you, missus, but I’d best see the master first.’

‘If you would like to wait here, I’ll go up and tell him now,’ Marianne told him.

She had closed the door to the master bedroom when she had last left it, but now it was slightly ajar. She rapped briefly on it, and when there was no reply she opened it.

A tumble of clothes lay on the floor: the shirt the Master of Bellfield had been wearing, along with some undergarments. The room smelled of carbolic soap, and there were splashes of water leading from the bathroom.

It amazed Marianne that a man in as much pain as Mr Denshaw had felt it necessary to get out of bed, remove his clothes and wash himself. And whilst ordinarily she would have admired a person’s desire for cleanliness, on this occasion she was more concerned about the effect his actions might have had on his wound.

Without stopping to think, she bustled over to the bed, scolding him worriedly. ‘You should have called for me if you wanted to get out of bed.’

Immediately a naked hair-roughened male arm shot out from beneath the covers and a hard male hand grasped her arm.

‘And you would have washed me like a baby? I’m a man, Mrs Brown, and that ring on your finger and the marriage lines you claim go with it don’t entitle you to make free with my body as though it were a child’s.’

Marianne could feel her face burning with embarrassment.

‘Mr Gledhill is here,’ she told him in a stilted voice. ‘Shall I bring him up?’

‘Aye.’

‘I have spoken with Charlie Postlethwaite about the laundry. I have not had time to check the linen closet properly as yet, but I shall do my best to ensure that your nightshirts are…’

To her dismay it was a struggle for her not to look at his naked torso as she spoke of the item of clothing he should surely have been wearing.

‘Nightshirts?’ He laughed and told her mockingly, ‘I am a mill master, Mrs Brown, not a gentleman, and I sleep in the garment that nature provided me with—my own skin. That is the best covering within the marital bed, for both a man and a woman.’

Marianne whisked herself out of the room, not trusting herself to make any reply.

For a man who had injured himself as badly as he had, the Master of Bellfield had a far too virile air about him. Her heart was beating far too fast. She had never before seen such muscles in a man’s arms, nor such breadth to a man’s chest, and as for that arrowing of dark hair…Marianne almost missed her step on the stairs, and her face was still glowing a bright pink when she hurried into the kitchen to find Mr Gledhill rocking the baby’s basket and the chair beside the fire empty.

‘T’babby woke up and started mithering.’

‘I expect he’s hungry,’ Marianne told him.

‘Aye, he is an all, by the looks of it. Got a little ’un of me own—a grand lad, he is,’ he told her proudly. ‘I’ve sent t’nurse packing for you, an’ all. Aye, and I’ve put the bolt across t’back door in case she were thinking of coming back and filling her pockets. A bad lot, she is. There’s more than one family round here ’as lost someone on account of her. After what happened to the master’s missus, me wife said as how she’d rather t’shepherd from t’farm deliver our wean than Dr Hollingshead.’

‘I’ll take you up to Mr Denshaw now, if you’d like to come this way?’

This time when she knocked on the bedroom door and then opened it Marianne purposefully did not look in the direction of the bed, but instead kept her face averted when she announced the mill manager, and then stepped smartly out of the room.

It was some time before the mill manager returned to the kitchen, and when he did he was frowning, as though his thoughts burdened him.

‘T’master has told me to tell you that for so long as he is laid up you can apply to me for whatever you may need in your role as housekeeper. He said that you’re to supply me with a list of everything that needs replacin’—by way of sheeting and that. I’m to have a word with the tradesmen and tell them to send their bills to me until t’master is well enough to deal wi’ them himself. There are accounts at most of the shops.’

He reached into his pocket and withdrew some bright shiny coins, which he placed on the table.

‘He said to give you this. There’s two guineas there in shillings. You’re to keep a record of what you spend for t’master to check. If there is anything else I can ’elp you with…’

‘There is one thing,’ Marianne told him. ‘The house is cold and damp, and I should like to have a fire lit in the master’s bedroom. There is a coal store, but there does not seem to be anyone to maintain it, nor to provide the household with kindling and the like.’

The mill manager nodded his head. ‘T’master said himself that he wanted me to sort out a lad to take the place of old Bert, who used to do the outside work. Should have been replaced years ago, he should, but t’master said as ’ow he’d worked ’ere all his life, and that it weren’t right to turn him out. Not that ’e’d been doing much work this last year. ‘The mill manager shook his head. ‘Too soft-’earted t’master is sometimes.’

Marianne couldn’t help but look surprised. Soft-hearted wasn’t how she would have described the Master of Bellfield.

‘I’ll send a lad up first thing in the morning. I know the very one. Good hard worker, he’ll be, and knows what he’s about. Master said that you’ll be needing a girl to do the rough work as well.’

Marianne nodded her head.

For a man who less than a handful of hours ago had barely been conscious, her new employer seemed to have made a remarkable recovery.

‘And perhaps if Mr Denshaw could have a manservant, especially whilst he is so…so awkwardly placed with his wound?’ Marianne suggested delicately.

The mill manager scratched his head. ‘Begging your pardon, ma’am, but I don’t think he’d care for that. He doesn’t like all them fancy ways. Mind, I could send up a couple of lads, if you were to send word, to give you a hand if it were a matter of lifting him or owt like that?’

‘Yes…thank you.’

He meant well, Marianne knew, but that wasn’t what she’d had in mind at all. With the nurse dismissed, she was now going to have to nurse her employer, and if what she had experienced earlier was anything to go by, the Master of Bellfield was not going to change his ways to accommodate her female sensibilities.

‘T’master also said to tell you that you can have the use of the housekeeper’s rooms, fifteen guineas wages a year and a scuttle full of coal every day, all found.’

Fifteen guineas! And all found! Marianne nodded her head. Those were generous terms indeed.

CHAPTER SIX

THE day’s bright sunshine had faded into evening darkness, and beneath the full moon which Marianne could see from the kitchen window the yard was glazed with white frosting.

True to his word, the mill manager had sent up a sturdy-looking youth who had spent what was left of the afternoon chopping fire kindling and filling enough coal scuttles to fuel every fire in the house.

At four o’clock Marianne had gone out to him to take him some bread and cheese. He seemed a decent lad, shy, and not quick with his words, but hard-working. He had told her his name was Ben. He had further added that his cousin Hannah would be coming up in the morning, to see if she might suit for the rough work in the kitchen.

A cheerful-looking individual had also arrived, announcing that he was from the laundry, and Marianne had somehow made time to bundle up and list as much of the grubby linen as she could.

She had even had time to run up the stairs to the attic floor, to seek out the rooms the mill manager had referred to as the housekeeper’s rooms. It had been easy enough to establish which they were, and Marianne had decided the minute she saw them that neither she nor the baby would be occupying them until she had given them a good scrub through and got some fresh ticking to cover the mattress. For tonight she planned to sleep in the kitchen again, where it was warm and clean.

The house’s nurseries were also on the attic floor, and Marianne had been drawn to them. Once they would have rung with the childish laughter of the young boy and girl whom, so local gossip said, had been driven away by the cruelty of the man who had been stepfather to one and guardian to the other.

The rooms were cold and abandoned, with distemper flaking off the sloping walls where they rose to meet the ceiling. Heavy protective bars guarded the windows, and there was a large brass fireguard in front of the fire, the kind on which a children’s nanny would have dried their outside clothes, and perhaps as a treat made toast for nursery tea.

One thing that had impressed her about the house was the fact that the nursery floor had a proper bathroom, with a flushing lavatory and a big bath.

Now, though, she was busy in the kitchen, keeping an eye on the baby whilst she worked busily.

Although she had been upstairs several times, on each occasion the Master of Bellfield had been sleeping, so Marianne had not disturbed him. Now the kitchen was full of the rich smell of the chicken soup she had made for the invalid, and the cat, who had proudly presented her with three dead mice already, was sitting purposefully in front of the range.

As she bustled about, Marianne hummed softly under her breath, mentally making lists of all that she had to do. There was the warming pan to be made ready for the master’s bed. Thanks to Ben, there was now a fire burning cheerfully in the bedroom, and tomorrow she would send Ben down to the mill to ask Mr Gledhill if he had any idea where she might find the boiler that should provide hot water for the bathrooms. She suspected it would be in the cellars, but she was reluctant to go down and investigate, knowing that it was by the door that led to them that the cat sat, waiting for her prey. The thought of mice running over her feet as she explored the cellars’ darkness made her shudder.

That meant that she must heat water on the range, both to clean the master’s wound and for him to shave with, should he choose to do so.

It had caused her several moments’ disquiet to discover that nowhere in the linen cupboard was there a sign of any kind of male night attire. There must, however, be a draper’s shop in the town, and they would be sure to be able to supply some, she decided firmly. Whether or not Mr Denshaw would wear them was, of course, another matter.

She let the cat out and, covering the soup and leaving it to simmer, gathered up everything she needed to wash and bandage her employer’s injury.

This time when she knocked on the door and turned the door handle the Master of Bellfield was not only awake, he was also sitting up, leaning back against the pillows and frowning as he stared out of the uncurtained windows.

‘Who gave orders for a fire to be lit?’ he demanded brusquely.

‘I did,’ Marianne told him. ‘When a person has received a wound of the magnitude of yours, then it is important that they are kept warm. I have brought you some water and some clean towels in case you wish to…to refresh yourself, before I bring up your supper. But first I must check your…your injury.’

‘My injury can look after itself.’

Marianne stood her ground. ‘I am relieved that you feel recovered enough to think so, sir, but I would rather check.’

‘Very well, then, but I warn you that my belly is empty, and I am in no mood to be fussed over like a mewling babe in arms.’

Marianne ignored him, dragging a chair over to the side of the bed instead and then laying a clean cloth on it.

‘What is that for?’

‘I thought that you could rest your leg on it whilst I cleaned the wound, so as not to dampen the sheets,’ Marianne told him calmly.

‘You want me to place my leg on the chair, do you?’

‘If you would be so kind, sir, yes.’

So far Marianne had managed to keep her gaze fixed on the wallpaper above his head, and thus avoid having to look at his naked chest, but now, as he moved, the sheet slipped down to reveal more of his torso, at the same time as he pushed his naked leg free of the bedding to rest it on the chair.

Marianne’s throat went dry. On this side of the bed at least there was nothing covering him except the shadows of the bed, which mercifully covered those parts of him she should not see. But in order to reach the site of his injury she would have to lean over him, and then…

What was the matter with her? She had attended other injured men, and nursed a dying husband to his death, sponging his whole fever-soaked body over and over again through those long hours.

But this man was different. This man touched something within her womanhood that she had no power to control. Marianne looked towards the door. It was too late for flight now. She had given her word and must stay, no matter what the cost to herself.

Taking a deep breath, she removed the cloth from the wound. The bleeding had stopped, but there was an ominous swollen reddening of the flesh around the puncture. Very gently Marianne placed her hand over it, her heart sinking when she felt its heat. The wound was becoming putrid.

‘Imagining me dead already, are you?’

The harsh words made her flinch.

‘The wound has some heat, sir, but I doubt that you will die of that,’ she told him, with more conviction that she felt. ‘I shall cleanse it and bandage it, and then if the heat has not gone I believe you should send for Dr Hollingshead.’

‘That quack! I’ll not have him near me.’

‘Perhaps another doctor, then?’

‘Aye, perhaps I should get myself one from Manchester—like my new housekeeper,’ he taunted her.

Marianne said nothing, getting up instead to fetch what she had brought with her.

She wiped the wound clean first with boiled water, using fresh pads as hot as she thought he could bear to draw the poison as her aunt had taught her, whilst keeping an eye on him to make sure that she was not causing him more pain than he could stand. And then, when she had done that, she reached for the honey.

‘What the devil do you mean to do with that?’ her patient demanded angrily, attempting to draw his leg out of the way.

‘It is honey, sir. My aunt believed that it has great efficacy in the drawing and healing of wounds.’

‘Well, I’m having none of it. Douse the injury with brandy and then wrap it up clean, and let’s have done with it.’

Marianne could see that he meant what he was saying. Reluctantly she did as he bade. She could not swear to it, but as she secured the clean bandage over the wound she feared that his flesh already possessed more heat.

‘I will go downstairs now and bring your supper, sir.’

His brusque nod told her that he was in more pain than he wanted her to see, she acknowledged as she hurried back to the kitchen.

A faint scratch at the back door told Marianne that the cat had returned and wanted to be let in. When she opened the door she saw that whilst she had been attending to her patient the sky had clouded over and it had started to snow, the flakes whirling in such a dizzy frenzy that she couldn’t see across the yard.

Shivering, she closed and then locked the door.

She had found blankets and pillows in the linen cupboards that would suffice for now, and had made herself a bed up on the settle. The range was stoked up for the night and banked down, and the kitchen clean and warm.

The baby, more lively now, held up his arms to her and smiled.

‘You should be asleep,’ she reproved him as she lifted him from the basket. Surely he was fatter and heavier already.

Marianne laughed to see the eagerness with which he took the small spoonfuls of soup she fed him, laughing again when he crowed happily at the sound of her laughter. The nurse might have wanted to see him swaddled, but Marianne could see his pleasure in being able to wriggle and kick out his legs.

‘My, but your daddy would be proud of you,’ she told him emotionally. There had been so many times during the arduous journey here when she had asked herself if she was doing the right thing, and now that he was here she was no closer to knowing the answer.

According to the nurse and the doctor, the Master of Bellfield was a man who had treated his late wife cruelly, abandoning her in her hour of need and leaving her to die along with his child. He was a man who had driven away his stepson, surely his rightful heir, and had caused the disappearance of the young innocent girl in his care.

But then his mill manager had spoken highly and warmly of him, and so had others. Who was to be believed? The baby yawned and closed his eyes. Tenderly Marianne carried him to his basket and laid him in it, kissing his forehead as she did so.

It was gone ten o’clock and she was tired. Once she had cleaned the housekeeper’s rooms on the attic floor she could enjoy the luxury of its bathroom, but for tonight she would have to make do with a wash here in front of the fire. Even that was a luxury compared with what she had known in the workhouse.

She started to take down her hair, ready to brush it. She had no nightgown to wear and would have to sleep in her chemise. Perhaps Mr Gledhill might know of somewhere where she could buy some serviceable lengths of flannelette. There was a sewing machine in the nursery, and her nimble fingers would soon be able to fashion some much needed new clothes for the baby and for herself.

Fashionable ladies might wear the new ‘health’ corsets beneath their expensive gowns, to emphasise the sought-after S-shaped curve that the King so admired, but even if she could have afforded such a garment there would have been no point in her wasting good money on it, Marianne reflected, for she had no one who might fasten it up for her.

Tears weren’t very far away as her meandering thoughts brought home to her how very alone she now was. All those she had loved had gone, though her beloved aunt thankfully would never know how cruelly her much-loved orphaned niece had been treated by those who should have cared for her. Her aunt’s estate, which should have been hers, had been sold over her head to pay off a bank loan Marianne was sure had never really existed, but at seventeen she had been too young and powerless to be able to prove it.

Life in the workhouse had come as a terrible shock to a young girl reared so gently. But it had been there that she had met and lost her very best and dearest friend.

And her husband. Poor Milo. He had fought so hard to live. She had seen how much he wanted to do so from the look in his eyes when he had asked her to place the baby in his arms one time. Tears stung her eyes, but she wiped them away. She was here in Rawlesden now, where Milo had wanted her to be.

A dab of salt on her finger, brushed round her mouth and then rinsed away, would have to serve to clean her teeth for tonight, and she summoned the courage to push her sad thoughts to one side. She must ask Mr Gledhill if he would authorise an advance on her wages, she decided, so that she could buy a few small personal necessities.

She was so tired that her eyes were closing as soon as she lay down on the settle beneath the blankets she had found.

Outside the snow whirled and fell in the biting cold, obliterating the landscape in deep drifts.

Marianne woke abruptly out of the dream she had been having. Her body felt warm but her mind was not at rest. She thought about the man upstairs and the ominous heat she had felt round his wound. Pushing back the blankets, she swung her feet to the floor.

It was not her responsibility to worry about him, but somehow she could not help but do so.

That flushed and discoloured wound and what it might portend was preying on her mind.

He would be sleeping, of course, she told herself as she lit a lantern, her toes curling in protest against the cold of the stone floor. And no doubt he would be angry with her if she woke him. But she knew that she would not rest until she had done as her aunt’s training was urging her and checked the wound, in case her fears weren’t merely in her imagination.

The lantern light cast moving shadows on the stair wall, elongating her own petite frame, so that it almost seemed to Marianne that as she climbed the stairs others climbed them with her.

In turn, that led her to think of the other women who had climbed these stairs before her, like the master’s neglected wife, her heart perhaps even more heavy than her body as she fought against her too-early labour pains.

And what of the wife’s niece? Had she too climbed these stairs in dread?

This house had known so much unhappiness and so much death. It needed the laughter of happy young voices to drive away its sadness.

The lantern highlighted darker patches on the landing wallpaper she had not noticed before, where a trio of paintings must have once hung. The chill of the unheated space drove Marianne on until she reached the master’s bedroom. She paused before turning the handle and opening the door.

A fire still burned in the grate, but surely it wasn’t just its glow that was responsible for the flush burning on the face of the man asleep in the bed. His breathing was rapid and unsteady, his body jerking in small spasms, as though even in his sleep he was in pain. His face was turned towards the window. On the table beside the bed she could see the bottle of brandy and an empty glass.

Marianne shivered. Were her worst fears to be realised? Putting down the lantern, she walked over to the bed. Leaning down, she placed her hand against its occupant’s forehead and then snatched it back again as she felt its heat, knowing that she would have to check his wound. She could smell the brandy he had drunk, no doubt to help him sleep and to dull the pain.

If the feverish heat of his face was anything to go by then his injury had indeed turned putrid. As she went to the other side of the bed Marianne prayed that she would not see on his thigh the tell-tale red line her aunt had warned her meant that the poison was spreading.

She prayed also that the brandy he had drunk would keep him asleep, because this time she intended to have her way and make sure that some cleansing honey was applied to his wound.

He winced when she removed the bedcovers, his face contorting in a spasm of pain, but he did not wake. In the light of the lantern Marianne could see what she had hoped she might not. His thigh was swollen, its flesh drawn tight and shiny, but when she looked closer she saw thankfully there was no red line. It smelled of heat and blood, but not of putrescence.

She worked as quickly as she could, using boiled and cooled water to draw the heat from the wound, and then covering the site with honey before rebandaging it.

She had worked so intently and so swiftly that she was slightly out of breath, her own flesh warm from her exertion.

Thankfully, through all that she had had to do, the Master of Bellfield had never once opened his eyes, although she had heard him groan on several occasions. Now, with her task completed, she replaced the covers and then, like any good nurse, went round the bed to its head, so that she might straighten the pillows and draw the sheet up to cover at least some of that disturbing breadth of male chest.