Полная версия

Полная версияA Little Tour of France

It was not to be looked at in that manner that one had come all the way from Tours; so that within ten minutes after my arrival I sallied out into the darkness to form somehow and somewhere a happier relation. However late in the evening I may arrive at a place, I never go to bed without my impression. The natural place at Bourges to look for it seemed to be the cathedral; which, moreover, was the only thing that could account for my presence dans cette galère. I turned out of a small square in front of the hotel and walked up a narrow, sloping street paved with big, rough stones and guiltless of a footway. It was a splendid starlight night; the stillness of a sleeping ville de province was over everything; I had the whole place to myself. I turned to my right, at the top of the street, where presently a short, vague lane brought me into sight of the cathedral. I approached it obliquely, from behind; it loomed up in the darkness above me enormous and sublime. It stands on the top of the large but not lofty eminence over which Bourges is scattered—a very good position as French cathedrals go, for they are not all so nobly situated as Chartres and Laon. On the side on which I approached it (the south) it is tolerably well exposed, though the precinct is shabby; in front, it is rather too much shut in. These defects, however, it makes up for on the north side and behind, where it presents itself in the most admirable manner to the garden of the Archevêché, which has been arranged as a public walk, with the usual formal alleys of the jardin français. I must add that I appreciated these points only on the following day. As I stood there in the light of the stars, many of which had an autumnal sharpness, while others were shooting over the heavens, the huge, rugged vessel of the church overhung me in very much the same way as the black hull of a ship at sea would overhang a solitary swimmer. It seemed colossal, stupendous, a dark leviathan.

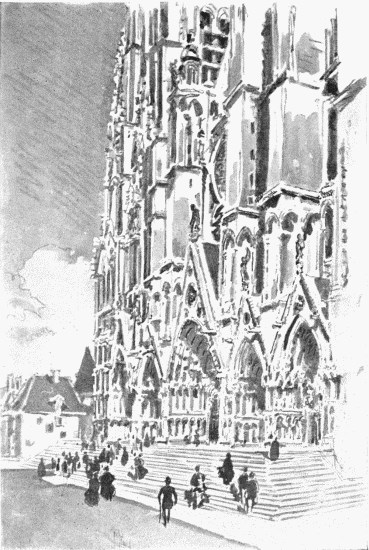

The next morning, which was lovely, I lost no time in going back to it, and found with satisfaction that the daylight did it no injury. The cathedral of Bourges is indeed magnificently huge, and if it is a good deal wanting in lightness and grace, it is perhaps only the more imposing. I read in the excellent handbook of M. Joanne that it was projected "dès 1172," but commenced only in the first years of the thirteenth century. "The nave," the writer adds, "was finished tant bien que mal, faute de ressources; the façade is of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in its lower part, and of the fourteenth in its upper." The allusion to the nave means the omission of the transepts. The west front consists of two vast but imperfect towers; one of which (the south) is immensely buttressed, so that its outline slopes forward like that of a pyramid. This is the taller of the two. If they had spires these towers would be prodigious; as it is, given the rest of the church, they are wanting in elevation. There are five deeply recessed portals, all in a row, each surmounted with a gable, the gable over the central door being exceptionally high. Above the porches, which give the measure of its width, the front rears itself, piles itself, on a great scale, carried up by galleries, arches, windows, sculptures, and supported by the extraordinarily thick buttresses of which I have spoken and which, though they embellish it with deep shadows thrown sidewise, do not improve its style. The portals, especially the middle one, are extremely interesting; they are covered with curious early sculptures. The middle one, however, I must describe alone. It has no less than six rows of figures—the others have four—some of which, notably the upper one, are still in their places. The arch at the top has three tiers of elaborate imagery. The upper of these is divided by the figure of Christ in judgment, of great size, stiff and terrible, with outstretched arms. On either side of him are ranged three or four angels, with the instruments of the Passion. Beneath him in the second frieze stands the angel of justice with the scales; and on either side of him is the vision of the last judgment. The good prepare, with infinite titillation and complacency, to ascend to the skies; while the bad are dragged, pushed, hurled, stuffed, crammed, into pits and caldrons of fire. There is a charming detail in this section. Beside the angel, on the right, where the wicked are the prey of demons, stands a little female figure, that of a child, who, with hands meekly folded and head gently raised, waits for the stern angel to decide upon her fate. In this fate, however, a dreadful big devil also takes a keen interest: he seems on the point of appropriating the tender creature; he has a face like a goat and an enormous hooked nose. But the angel gently lays a hand upon the shoulder of the little girl—the movement is full of dignity—as if to say: "No; she belongs to the other side." The frieze below represents the general resurrection, with the good and the wicked emerging from their sepulchres. Nothing can be more quaint and charming than the difference shown in their way of responding to the final trump. The good get out of their tombs with a certain modest gaiety, an alacrity tempered by respect; one of them kneels to pray as soon as he has disinterred himself. You may know the wicked, on the other hand, by their extreme shyness; they crawl out slowly and fearfully; they hang back, and seem to say "Oh, dear!" These elaborate sculptures, full of ingenuous intention and of the reality of early faith, are in a remarkable state of preservation; they bear no superficial signs of restoration and appear scarcely to have suffered from the centuries. They are delightfully expressive; the artist had the advantage of knowing exactly the effect be wished to produce.

The Bourges: the Cathedral interior of the cathedral has a great simplicity and majesty and, above all, a tremendous height. The nave is extraordinary in this respect; it dwarfs everything else I know. I should add, however, that I am in architecture always of the opinion of the last speaker. Any great building seems to me while I look at it the ultimate expression. At any rate, during the hour that I sat gazing along the high vista of Bourges the interior of the great vessel corresponded to my vision of the evening before. There is a tranquil largeness, a kind of infinitude, about such an edifice; it soothes and purifies the spirit, it illuminates the mind. There are two aisles, on either side, in addition to the nave—five in all—and, as I have said, there are no transepts; an omission which lengthens the vista, so that from my place near the door the central jewelled window in the depths of the perpendicular choir seemed a mile or two away. The second or outward of each pair of aisles is too low and the first too high; without this inequality the nave would appear to take an even more prodigious flight. The double aisles pass all the way round the choir, the windows of which are inordinately rich in magnificent old glass. I have seen glass as fine in other churches, but I think I have never seen so much of it at once.

Beside the cathedral, on the north, is a curious structure of the fourteenth or fifteenth century, which looks like an enormous flying buttress, with its support, sustaining the north tower. It makes a massive arch, high in the air, and produces a romantic effect as people pass under it to the open gardens of the Archevêché, which extend to a considerable distance in the rear of the church. The structure supporting the arch has the girth of a largeish house, and contains chambers with whose uses I am unacquainted, but to which the deep pulsations of the cathedral, the vibration of its mighty bells and the roll of its organ-tones must be transmitted even through the great arm of stone.

The archiepiscopal palace, not walled in as at Tours, is visible as a stately habitation of the last century, at the time of my visit under repair after a fire. From this side and from the gardens of the palace the nave of the cathedral is visible in all its great length and height, with its extraordinary multitude of supports. The gardens aforesaid, accessible through tall iron gates, are the promenade—the Tuileries—of the town, and, very pretty in themselves, are immensely set off by the overhanging church. It was warm and sunny; the benches were empty; I sat there a long time in that pleasant state of mind which visits the traveller in foreign towns, when he is not too hurried, while he wonders where he had better go next. The straight, unbroken line of the roof of the cathedral was very noble; but I could see from this point how much finer the effect would have been if the towers, which had dropped almost out of sight, might have been carried still higher. The archiepiscopal gardens look down at one end over a sort of esplanade or suburban avenue lying on a lower level on which they open, and where several detachments of soldiers (Bourges is full of soldiers) had just been drawn up. The civil population was also collecting, and I saw that something was going to happen. I learned that a private of the Chasseurs was to be "broken" for stealing, and every one was eager to behold the ceremony. Sundry other detachments arrived on the ground, besides many of the military who had come as a matter of taste. One of them described to me the process of degradation from the ranks, and I felt for a moment a hideous curiosity to see it, under the influence of which I lingered a little. But only a little; the hateful nature of the spectacle hurried me away at the same that others were hurrying forward. As I turned my back upon it I reflected that human beings are cruel brutes, though I could not flatter myself that the ferocity of the thing was exclusively French. In another country the concourse would have been equally great, and the moral of it all seemed to be that military penalties are as terrible as military honours are gratifying.

Chapter xii

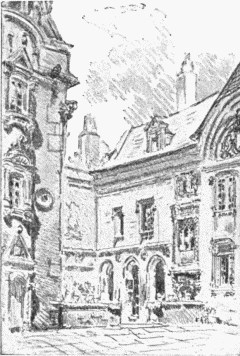

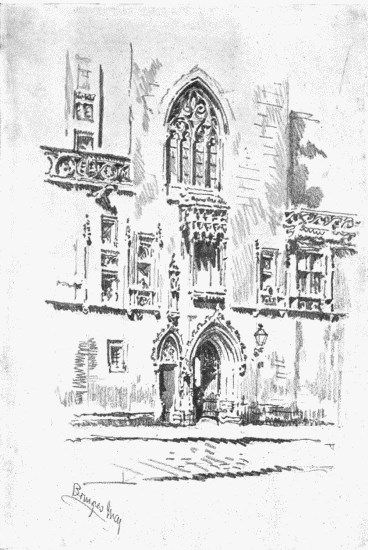

Bourges: Jacques CœurTHE cathedral is not the only lion of Bourges; the house of Jacques Cœur awaits you in posture scarcely less leonine. This remarkable man had a very strange history, and he too was "broken" like the wretched soldier whom I did not stay to see. He has been rehabilitated, however, by an age which does not fear the imputation of paradox, and a marble statue of him ornaments the street in front of his house. To interpret him according to this image—a womanish figure in a long robe and a turban, with big bare arms and a dramatic pose—would be to think of him as a kind of truculent sultana. He wore the dress of his period, but his spirit was very modern; he was a Vanderbilt or a Rothschild of the fifteenth century. He supplied the ungrateful Charles VII. with money to pay the troops who, under the heroic Maid, drove the English from French soil. His house, which to-day is used as a Palais de Justice, appears to have been regarded at the time it was built very much as the residence of Mr. Vanderbilt is regarded in New York to-day. It stands on the edge of the hill on which most of the town is planted, so that, behind, it plunges down to a lower level, and, if you approach it on that side, as I did, to come round to the front of it you have to ascend a longish flight of steps. The back, of old, must have formed a portion of the city wall; at any rate it offers to view two big towers which Joanne says were formerly part of the defence of Bourges. From the lower level of which I speak—the square in front of the post-office—the palace of Jacques Cœur looks very big and strong and feudal; from the upper street, in front of it, it looks very handsome and delicate. To this street it presents two tiers and a considerable length of façade; and it has both within and without a great deal of curious and beautiful detail. Above the portal, in the stonework, are two false windows, in which two figures, a man and a woman, apparently household servants, are represented, in sculpture, as looking down into the street. The effect is homely, yet grotesque, and the figures are sufficiently living to make one commiserate them for having been condemned, in so dull a town, to spend several centuries at the window. They appear to be watching for the return of their master, who left his beautiful house one morning and never came back.

Bourges—THE HOUSE OF JACQUES CŒUR

The Bourges: Jacques Cœur history of Jacques Cœur, which has been written by M. Pierre Clément in a volume crowned by the French Academy, is very wonderful and interesting, but I have no space to go into it here. There is no more curious example, and few more tragical, of a great fortune crumbling from one day to the other, or of the antique superstition that the gods grow jealous of human success. Merchant, millionaire, banker, ship-owner, royal favourite and minister of finance, explorer of the East and monopolist of the glittering trade between that quarter of the globe and his own, great capitalist who had anticipated the brilliant operations of the present time, he expiated his prosperity by poverty, imprisonment, and torture. The obscure points in his career have been elucidated by M. Clément, who has drawn, moreover, a very vivid picture of the corrupt and exhausted state of France during the middle of the fifteenth century. He has shown that the spoliation of the great merchant was a deliberately calculated act, and that the king sacrificed him without scruple or shame to the avidity of a singularly villanous set of courtiers. The whole story is an extraordinary picture of high-handed rapacity—the crudest possible assertion of the right of the stronger. The victim was stripped of his property, but escaped with his life, made his way out of France and, betaking himself to Italy, offered his services to the Pope. It is proof of the consideration that he enjoyed in Europe, and of the variety of his accomplishments, that Calixtus III. should have appointed him to take command of a fleet which his Holiness was fitting out against the Turks. Jacques Cœur, however, was not destined to lead it to victory. He died shortly after the expedition had started, in the island of Chios, in 1456. The house at Bourges, his native place, testifies in some degree to his wealth and splendour, though it has in parts that want of space which is striking in many of the buildings of the Middle Ages. The court indeed is on a large scale, ornamented with turrets and arcades, with several beautiful windows and with sculptures inserted in the walls, representing the various sources of the great fortune of the owner. M. Pierre Clément describes this part of the house as having been of an "incomparable richesse"—an estimate of its charms which seems slightly exaggerated to-day. There is, however, something delicate and familiar in the bas-reliefs of which I have spoken, little scenes of agriculture and industry which show that the proprietor was not ashamed of calling attention to his harvests and enterprises. To-day we should question the taste of such allusions, even in plastic form, in the house of a "merchant prince" however self-made. Why should it be, accordingly, that these quaint little panels at Bourges do not displease us? It is perhaps because things very ancient never, for some mysterious reason, appear vulgar. This fifteenth-century millionaire, with his palace, his "swagger" sculptures, may have produced that impression on some critical spirits of his own day.

The portress who showed me into the building was a dear little old woman, with the gentlest, sweetest, saddest face—a little white, aged face, with dark, pretty eyes—and the most considerate manner. She took me up into an upper hall, where there were a couple of curious chimney-pieces and a fine old oaken roof, the latter representing the hollow of a long boat. There is a certain oddity in a native of Bourges—an inland town if ever there was one, without even a river (to call a river) to encourage nautical ambitions—having found his end as admiral of a fleet; but this boat-shaped roof, which is extremely graceful and is repeated in another apartment, would suggest that the imagination of Jacques Cœur was fond of riding the waves. Indeed, as he trafficked in Oriental products and owned many galleons, it is probable that he was personally as much at home in certain Mediterranean ports as in the capital of the pastoral Berry. If, when he looked at the ceilings of his mansion, he saw his boats upside down, this was only a suggestion of the shortest way of emptying them of their treasures. He is presented in person above one of the great stone chimney-pieces, in company with his wife, Macée de Léodepart—I like to write such an extraordinary name. Carved in white stone, the two sit playing at chess at an open window, through which they appear to give their attention much more to the passers-by than to the game. They are also exhibited in other attitudes; though I do not recognise them in the composition on top of one of the fireplaces which represents the battlements of a castle, with the defenders (little figures between the crenellations) hurling down missiles with a great deal of fury and expression. It would have been hard to believe that the man who surrounded himself with these friendly and humorous devices had been guilty of such wrong-doing as to call down the heavy hand of justice.

It is a curious fact, however, that Bourges contains legal associations of a purer kind than the prosecution of Jacques Cœur, which, in spite of the rehabilitations of history, can hardly be said yet to have terminated, inasmuch as the law-courts of the city are installed in his quondam residence. At a short distance from it stands the Hôtel Cujas, one of the curiosities of Bourges and the habitation for many years of the great jurisconsult who revived in the sixteenth century the study of the Roman law and professed it during the close of his life in the university of the capital of Berry. The learned Cujas had, in spite of his sedentary pursuits, led a very wandering life; he died at Bourges in the year 1590. Sedentary pursuits are perhaps not exactly what I should call them, having read in the "Biographie Universelle" (sole source of my knowledge of the renowned Cujacius) that his usual manner of study was to spread himself on his belly on the floor. He did not sit down, he lay down; and the "Biographie Universelle" has (for so grave a work) an amusing picture of the short, fat, untidy scholar dragging himself à plat ventre, across his room, from one pile of books to the other. The house in which these singular gymnastics took place, and which is now the headquarters of the gendarmerie, is one of the most picturesque at Bourges. Dilapidated and discoloured, it has a charming Renaissance front. A high wall separates it from the street, and on this wall, which is divided by a large open gateway, are perched two overhanging turrets. The open gateway admits you to the court, beyond which the melancholy mansion erects itself, decorated also with turrets, with fine old windows and with a beautiful tone of faded red brick and rusty stone. It is a charming encounter for a provincial by-street; one of those accidents in the hope of which the traveller with a propensity for sketching (whether on a little paper block or on the tablets of his brain) decides to turn a corner at a venture. A brawny gendarme in his shirtsleeves was polishing his boots in the court; an ancient, knotted vine, forlorn of its clusters, hung itself over a doorway and dropped its shadow on the rough grain of the wall. The place was very sketchable. I am sorry to say, however, that it was almost the only "bit." Various other curious old houses are supposed to exist at Bourges, and I wandered vaguely about in search of them. But I had little success, and I ended by becoming sceptical. Bourges is a ville de province in the full force of the term, especially as applied invidiously. The streets, narrow, tortuous, and dirty, have very wide cobble-stones; the houses for the most part are shabby, without local colour. The look of things is neither modern nor antique—a kind of mediocrity of middle age. There is an enormous number of blank walls—walls of gardens, of courts, of private houses—that avert themselves from the street as if in natural chagrin at there being so little to see. Round about is a dull, flat, featureless country, on which the magnificent cathedral looks down. There is a peculiar dulness and ugliness in a French town of this type, which, I must immediately add, is not the most frequent one. In Italy everything has a charm, a colour, a grace; even desolation and ennui. In England a cathedral city may be sleepy, but it is pretty sure to be mellow. In the course of six weeks spent en province, however, I saw few places that had not more expression than Bourges.

BOURGES—THE HOUSE OF JACQUES CŒUR

IBourges: Jacques Cœur went back to the cathedral; that, after all, was a feature. Then I returned to my hotel, where it was time to dine, and sat down, as usual, with the commis-voyageurs, who cut their bread on their thumb and partook of every course; and after this repast I repaired for a while to the café, which occupied a part of the basement of the inn and opened into its court. This café was a friendly, homely, sociable spot, where it seemed the habit of the master of the establishment to tutoyer his customers and the practice of the customers to tutoyer the waiter. Under these circumstances the waiter of course felt justified in sitting down at the same table with a gentleman who had come in and asked him for writing materials. He served this gentleman with a horrible little portfolio covered with shiny black cloth and accompanied with two sheets of thin paper, three wafers, and one of those instruments of torture which pass in France for pens—these being the utensils invariably evoked by such a request; and then, finding himself at leisure, he placed himself opposite and began to write a letter of his own. This trifling incident reminded me afresh that France is a democratic country. I think I received an admonition to the same effect from the free, familiar way in which the game of whist was going on just behind me. It was attended with a great deal of noisy pleasantry, flavoured every now and then with a dash of irritation. There was a young man of whom I made a note; he was such a beautiful specimen of his class. Sometimes he was very facetious, chattering, joking, punning, showing off; then, as the game went on and he lost and had to pay the consommation, he dropped his amiability, slanged his partner, declared he wouldn't play any more, and went away in a fury. Nothing could be more perfect or more amusing than the contrast. The manner of the whole affair was such as, I apprehend, one would not have seen among our English-speaking people; both the jauntiness of the first phase and the petulance of the second. To hold the balance straight, however, I may remark that if the men were all fearful "cads," they were, with their cigarettes and their inconsistency, less heavy, less brutal, than our dear English-speaking cad; just as the bright little café where a robust materfamilias, doling out sugar and darning a stocking, sat in her place under the mirror behind the comptoir, was a much more civilised spot than a British public-house or a "commercial room," with pipes and whisky, or even than an American saloon.

BOURGES: THE CATHEDRAL (WEST FRONT)

Chapter xiii

Le MansIT IS very certain that when I left Tours for Le Mans it was a journey and not an excursion; for I had no intention of coming back. The question indeed was to get away, no easy matter in France in the early days of October, when the whole jeunesse of the country is returning to school. It is accompanied, apparently, with parents and grandparents, and it fills the trains with little pale-faced lycéens, who gaze out of the windows with a longing, lingering air not unnatural on the part of small members of a race in which life is intense, who are about to be restored to those big educative barracks that do such violence to our American appreciation of the opportunities of boyhood. The train stopped every five minutes; but fortunately the country was charming—hilly and bosky, eminently good-humoured, and dotted here and there with a smart little château. The old capital of the province of the Maine, which has given its name to a great American State, is a fairly interesting town, but I confess that I found in it less than I expected to admire. My expectations had doubtless been my own fault; there is no particular reason why Le Mans should fascinate. It stands upon a hill, indeed—a much better hill than the gentle swell of Bourges. This hill, however, is not steep in all directions; from the railway, as I arrived, it was not even perceptible. Since I am making comparisons, I may remark that, on the other hand, the Boule d'Or at Le Mans is an appreciably better inn than the Boule d'Or at Bourges. It looks out upon a small market-place which has a certain amount of character and seems to be slipping down the slope on which it lies, though it has in the middle an ugly halle, or circular market-house, to keep it in position. At Le Mans, as at Bourges, my first business was with the cathedral, to which I lost no time in directing my steps. It suffered by juxtaposition to the great church I had seen a few days before; yet it has some noble features. It stands on the edge of the eminence of the town, which falls straight away on two sides of it, and makes a striking mass, bristling behind, as you see it from below, with rather small but singularly numerous flying buttresses. On my way to it I happened to walk through the one street which contains a few ancient and curious houses, a very crooked and untidy lane, of really mediæval aspect, honoured with the denomination of the Grand Rue. Here is the house of Queen Berengaria—an absurd name, as the building is of a date some three hundred years later than the wife of Richard Cœur de Lion, who has a sepulchral monument in the south aisle of the cathedral. The structure in question—very sketchable, if the sketcher could get far enough away from it—is an elaborate little dusky façade, overhanging the street, ornamented with panels of stone, which are covered with delicate Renaissance sculpture. A fat old woman standing in the door of a small grocer's shop next to it—a most gracious old woman, with a bristling moustache and a charming manner—told me what the house was, and also indicated to me a rotten-looking brown wooden mansion in the same street, nearer the cathedral, as the Maison Scarron. The author of the "Roman Comique" and of a thousand facetious verses enjoyed for some years, in the early part of his life, a benefice in the cathedral of Le Mans, which gave him a right to reside in one of the canonical houses. He was rather an odd canon, but his history is a combination of oddities. He wooed the comic muse from the arm-chair of a cripple, and in the same position—he was unable even to go down on his knees—prosecuted that other suit which made him the first husband of a lady of whom Louis XIV. was to be the second. There was little of comedy in the future Madame de Maintenon; though, after all, there was doubtless as much as there need have been in the wife of a poor man who was moved to compose for his tomb such an epitaph as this, which I quote from the "Biographie Universelle":