Полная версия

Полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 4 (of 9)

TO GENERAL KOSCIUSKO

Washington, April 2, 1802.Dear General,—It is but lately that I have received your letter of the 25th Frimaire (December 15) wishing to know whether some officers of your country could expect to be employed in this country. To prevent a suspense injurious to them, I hasten to inform you, that we are now actually engaged in reducing our military establishment one-third, and discharging one-third of our officers. We keep in service no more than men enough to garrison the small posts dispersed at great distances on our frontiers, which garrisons will generally consist of a captain's company only, and in no cases of more than two or three, in not one, of a sufficient number to require a field officer; and no circumstance whatever can bring these garrisons together, because it would be an abandonment of their forts. Thus circumstanced, you will perceive the entire impossibility of providing for the persons you recommend. I wish it had been in my power to give you a more favorable answer; but next to the fulfilling your wishes, the most grateful thing I can do is to give a faithful answer. The session of the first Congress convened since republicanism has recovered its ascendancy, is now drawing to a close. They will pretty completely fulfil all the desires of the people. They have reduced the army and navy to what is barely necessary. They are disarming executive patronage and preponderance, by putting down one-half the offices of the United States, which are no longer necessary. These economies have enabled them to suppress all the internal taxes, and still to make such provision for the payment of their public debt as to discharge that in eighteen years. They have lopped off a parasite limb, planted by their predecessors on their judiciary body for party purposes; they are opening the doors of hospitality to fugitives from the oppressions of other countries; and we have suppressed all those public forms and ceremonies which tended to familiarize the public eye to the harbingers of another form of government. The people are nearly all united; their quondam leaders, infuriated with the sense of their impotence, will soon be seen or heard only in the newspapers, which serve as chimneys to carry off noxious vapors and smoke, and all is now tranquil, firm and well, as it should be. I add no signature because unnecessary for you. God bless you, and preserve you still for a season of usefulness to your country.

TO ROBERT R. LIVINGSTON

Washington, April 18, 1802.Dear Sir,—A favorable and confidential opportunity offering by M. Dupont de Nemours, who is revisiting his native country, gives me an opportunity of sending you a cypher to be used between us, which will give you some trouble to understand, but once understood, is the easiest to use, the most indecypherable, and varied by a new key with the greatest facility, of any I have ever known. I am in hopes the explanation enclosed will be sufficient.

* * * * * * * *But writing by Mr. Dupont, I need use no cypher. I require from him to put this into your own and no other hand, let the delay occasioned by that be what it will.

The cession of Louisiana and the Floridas by Spain to France, works most sorely on the United States. On this subject the Secretary of State has written to you fully, yet I cannot forbear recurring to it personally, so deep is the impression it makes on my mind. It completely reverses all the political relations of the United States, and will form a new epoch in our political course. Of all nations of any consideration, France is the one which, hitherto, has offered the fewest points on which we could have any conflict of right, and the most points of a communion of interests. From these causes, we have ever looked to her as our natural friend, as one with which we never could have an occasion of difference. Her growth, therefore, we viewed as our own, her misfortunes ours. There is on the globe one single spot, the possessor of which is our natural and habitual enemy. It is New Orleans, through which the produce of three-eighths of our territory must pass to market, and from its fertility it will ere long yield more than half of our whole produce, and contain more than half of our inhabitants. France, placing herself in that door, assumes to us the attitude of defiance. Spain might have retained it quietly for years. Her pacific dispositions, her feeble state, would induce her to increase our facilities there, so that her possession of the place would be hardly felt by us, and it would not, perhaps, be very long before some circumstance might arise, which might make the cession of it to us the price of something of more worth to her. Not so can it ever be in the hands of France: the impetuosity of her temper, the energy and restlessness of her character, placed in a point of eternal friction with us, and our character, which, though quiet and loving peace and the pursuit of wealth, is high-minded, despising wealth in competition with insult or injury, enterprising and energetic as any nation on earth; these circumstances render it impossible that France and the United States can continue long friends, when they meet in so irritable a position. They, as well as we, must be blind if they do not see this; and we must be very improvident if we do not begin to make arrangements on that hypothesis. The day that France takes possession of New Orleans, fixes the sentence which is to restrain her forever within her low-water mark. It seals the union of two nations, who, in conjunction, can maintain exclusive possession of the ocean. From that moment, we must marry ourselves to the British fleet and nation. We must turn all our attention to a maritime force, for which our resources place us on very high ground; and having formed and connected together a power which may render reinforcement of her settlements here impossible to France, make the first cannon which shall be fired in Europe the signal for the tearing up any settlement she may have made, and for holding the two continents of America in sequestration for the common purposes of the United British and American nations. This is not a state of things we seek or desire. It is one which this measure, if adopted by France, forces on us as necessarily, as any other cause, by the laws of nature, brings on its necessary effect. It is not from a fear of France that we deprecate this measure proposed by her. For however greater her force is than ours, compared in the abstract, it is nothing in comparison of ours, when to be exerted on our soil. But it is from a sincere love of peace, and a firm persuasion, that bound to France by the interests and the strong sympathies still existing in the minds of our citizens, and holding relative positions which insure their continuance, we are secure of a long course of peace. Whereas, the change of friends, which will be rendered necessary if France changes that position, embarks us necessarily as a belligerent power in the first war of Europe. In that case, France will have held possession of New Orleans during the interval of a peace, long or short, at the end of which it will be wrested from her. Will this short-lived possession have been an equivalent to her for the transfer of such a weight into the scale of her enemy? Will not the amalgamation of a young, thriving nation, continue to that enemy the health and force which are at present so evidently on the decline? And will a few years' possession of New Orleans add equally to the strength of France? She may say she needs Louisiana for the supply of her West Indies. She does not need it in time of peace, and in war she could not depend on them, because they would be so easily intercepted. I should suppose that all these considerations might, in some proper form, be brought into view of the government of France. Though stated by us, it ought not to give offence; because we do not bring them forward as a menace, but as consequences not controllable by us, but inevitable from the course of things. We mention them, not as things which we desire by any means, but as things we deprecate; and we beseech a friend to look forward and to prevent them for our common interest.

If France considers Louisiana, however, as indispensable for her views, she might perhaps be willing to look about for arrangements which might reconcile it to our interests. If anything could do this, it would be the ceding to us the island of New Orleans and the Floridas. This would certainly, in a great degree, remove the causes of jarring and irritation between us, and perhaps for such a length of time, as might produce other means of making the measure permanently conciliatory to our interests and friendships. It would, at any rate, relieve us from the necessity of taking immediate measures for countervailing such an operation by arrangements in another quarter. But still we should consider New Orleans and the Floridas as no equivalent for the risk of a quarrel with France, produced by her vicinage.

I have no doubt you have urged these considerations, on every proper occasion, with the government where you are. They are such as must have effect, if you can find means of producing thorough reflection on them by that government. The idea here is, that the troops sent to St. Domingo, were to proceed to Louisiana after finishing their work in that island. If this were the arrangement, it will give you time to return again and again to the charge. For the conquest of St. Domingo will not be a short work. It will take considerable time, and wear down a great number of soldiers. Every eye in the United States is now fixed on the affairs of Louisiana. Perhaps nothing since the revolutionary war, has produced more uneasy sensations through the body of the nation. Notwithstanding temporary bickerings have taken place with France, she has still a strong hold on the affections of our citizens generally. I have thought it not amiss, by way of supplement to the letters of the Secretary of State, to write you this private one, to impress you with the importance we affix to this transaction. I pray you to cherish Dupont. He has the best disposition for the continuance of friendship between the two nations, and perhaps you may be able to make a good use of him.

Accept assurances of my affectionate esteem and high consideration.

TO M. DUPONT DE NEMOURS

Washington, April 25, 1802.Dear Sir,—The week being now closed, during which you had given me a hope of seeing you here, I think it safe to enclose you my letters for Paris, lest they should fail of the benefit of so desirable a conveyance. They are addressed to Kosciugha, Madame de Corny, Mrs. Short, and Chancellor Livingston. You will perceive the unlimited confidence I repose in your good faith, and in your cordial dispositions to serve both countries, when you observe that I leave the letters for Chancellor Livingston open for your perusal. The first page respects a cypher, as do the loose sheets folded with the letter. These are interesting to him and myself only, and therefore are not for your perusal. It is the second, third, and fourth pages which I wish you to read to possess yourself of completely, and then seal the letter with wafers stuck under the flying seal, that it may be seen by nobody else if any accident should happen to you. I wish you to be possessed of the subject, because you may be able to impress on the government of France the inevitable consequences of their taking possession of Louisiana; and though, as I here mention, the cession of New Orleans and the Floridas to us would be a palliation, yet I believe it would be no more, and that this measure will cost France, and perhaps not very long hence, a war which will annihilate her on the ocean, and place that element under the despotism of two nations, which I am not reconciled to the more because my own would be one of them. Add to this the exclusive appropriation of both continents of America as a consequence. I wish the present order of things to continue, and with a view to this I value highly a state of friendship between France and us. You know too well how sincere I have ever been in these dispositions to doubt them. You know, too, how much I value peace, and how unwillingly I should see any event take place which would render war a necessary resource; and that all our movements should change their character and object. I am thus open with you, because I trust that you will have it in your power to impress on that government considerations, in the scale against which the possession of Louisiana is nothing. In Europe, nothing but Europe is seen, or supposed to have any right in the affairs of nations; but this little event, of France's possessing herself of Louisiana, which is thrown in as nothing, as a mere make-weight in the general settlement of accounts,—this speck which now appears as an almost invisible point in the horizon, is the embryo of a tornado which will burst on the countries on both sides of the Atlantic, and involve in its effects their highest destinies. That it may yet be avoided is my sincere prayer; and if you can be the means of informing the wisdom of Bonaparte of all its consequences, you have deserved well of both countries. Peace and abstinence from European interferences are our objects, and so will continue while the present order of things in America remain uninterrupted. There is another service you can render. I am told that Talleyrand is personally hostile to us. This, I suppose, has been occasioned by the X Y Z history. But he should consider that that was the artifice of a party, willing to sacrifice him to the consolidation of their power. This nation has done him justice by dismissing them; that those in power are precisely those who disbelieved that story, and saw in it nothing but an attempt to deceive our country; that we entertain towards him personally the most friendly dispositions; that as to the government of France, we know too little of the state of things there to understand what it is, and have no inclination to meddle in their settlement. Whatever government they establish, we wish to be well with it. One more request,—that you deliver the letter to Chancellor Livingston with your own hands, and, moreover, that you charge Madame Dupont, if any accident happen to you, that she deliver the letter with her own hands. If it passes only through hers and yours, I shall have perfect confidence in its safety. Present her my most sincere respects, and accept yourself assurances of my constant affection, and my prayers, that a genial sky and propitious gales may place you, after a pleasant voyage, in the midst of your friends.

TO MR. BARLOW

Washington, May 3, 1802.Dear Sir,—I have doubted whether to write to you, because yours of August 25th, received only March 27th, gives me reason to expect you are now on the ocean; however, as I know that voyages so important are often delayed, I shall venture a line by Mr. Dupont de Nemours. The Legislature rises this day. They have carried into execution, steadily almost, all the propositions submitted to them in my message at the opening of the session. Some few are laid over for want of time. The most material is the militia, the plan of which they cannot easily modify to their general approbation. Our majority in the House of Representatives has been about two to one; in the Senate, eighteen to fifteen. After another election it will be of two to one in the Senate, and it would not be for the public good to have it greater. A respectable minority is useful as censors. The present one is not respectable, being the bitterest remains of the cup of federalism, rendered desperate and furious by despair. A small check in the tide of republicanism in Massachusetts, which has showed itself very unexpectedly at the last election, is not accounted for. Everywhere else we are becoming one. In Rhode Island the late election gives us two to one through the whole State. Vermont is decidedly with us. It is said and believed that New Hampshire has got a majority of republicans now in its Legislature; and wanted a few hundreds only of turning out their federal Governor. He goes assuredly the next trial. Connecticut is supposed to have gained for us about fifteen or twenty per cent. since the last election; but the exact issue is not yet known here; nor is it certainly known how we shall stand in the House of Representatives of Massachusetts. In the Senate there we have lost ground. The candid federalists acknowledge that their party can never more raise its head. The operations of this session of Congress, when known among the people at large, will consolidate them. We shall now be so strong that we shall certainly split again; for freemen, thinking differently and speaking and acting as they think, will form into classes of sentiment. But it must be under another name. That of federalism is become so odious that no party can rise under it. As the division into whig and tory is founded in the nature of man; the weakly and nerveless, the rich and the corrupt, seeing more safety and accessibility in a strong executive; the healthy, firm, and virtuous, feeling a confidence in their physical and moral resources, and willing to part with only so much power as is necessary for their good government; and, therefore, to retain the rest in the hands of the many, the division will substantially be into whig and tory, as in England formerly. As yet no symptoms show themselves, nor will, till after another election. I am extremely happy to learn that you are so much at your ease, that you can devote the rest of your life to the information of others. The choice of a place of residence is material. I do not think you can do better than to fix here for awhile, till you can become again Americanized, and understand the map of the country. This may be considered as a pleasant country residence, with a number of neat little villages scattered around within the distance of a mile and a half, and furnishing a plain and substantially good society. They have begun their buildings in about four or five different points, at each of which there are buildings enough to be considered as a village. The whole population is about six thousand. Mr. Madison and myself have cut out a piece of work for you, which is to write the history of the United States, from the close of the war downwards. We are rich ourselves in materials, and can open all the public archives to you; but your residence here is essential, because a great deal of the knowledge of things is not on paper, but only within ourselves, for verbal communication. John Marshall is writing the life of General Washington from his papers. It is intended to come out just in time to influence the next presidential election. It is written, therefore, principally with a view to electioneering purposes. But it will consequently be out in time to aid you with information, as well as to point out the perversions of truth necessary to be rectified. Think of this, and agree to it; and be assured of my high esteem and attachment.

P. S. There is a most lovely seat adjoining this city, on a high hill, commanding a most extensive view of the Potomac, now for sale. A superb house, gardens, &c., with thirty or forty acres of ground. It will be sold under circumstances of distress, and will probably go for the half of what it has cost. It was built by Gustavus Scott, who is dead bankrupt.

TO MR. GALLATIN

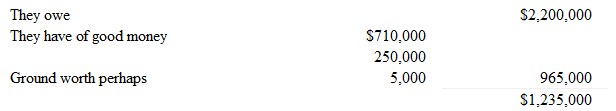

June 19, 1802.With respect to the bank of Pennsylvania, their difficulties proceed from excessive discounts. The $3,000,000 due to them comprehend doubtless all the desperate debts accumulated since their institution. Their buildings should only be counted at the value of the naked ground belonging to them; because, if brought to market, they are worth to private builders no more than their materials, which are known by experience to be worth no more than the cost of pulling down and removing them. Their situation then is

To pay which $1,235,000, they depend on $3,000,000 of debts due to them, the amount of which shows they are of long standing, a part desperate, a part not commandable. In this situation it does not seem safe to deposit public money with them, and the effect would only be to enable them to nourish their disease by continuing their excessive discounts, the checking of which is the only means of saving themselves from bankruptcy. The getting them to pay the Dutch debt, is but a deposit in another though a safer form. If we can with propriety recommend indulgence to the bank of the United States, it would be attended with the least danger to us of any of the measures suggested, but it is in fact asking that bank to lend to the one of Pennsylvania, that they may be enabled to continue lending to others. The monopoly of a single bank is certainly an evil. The multiplication of them was intended to cure it; but it multiplied an influence of the same character with the first, and completed the supplanting the precious metals by a paper circulation. Between such parties the less we meddle the better.

TO DOCTOR PRIESTLEY

Washington, June 19, 1802.Dear Sir,—Your favor of the 12th has been duly received, and with that pleasure which the approbation of the good and the wise must ever give. The sentiments it impresses are far beyond my merits or pretensions; they are precious testimonies to me however, that my sincere desire to do what is right and just is viewed with candor. That it should be handed to the world under the authority of your name is securing its credit with posterity. In the great work which has been effected in America, no individual has a right to take any great share to himself. Our people in a body are wise, because they are under the unrestrained and unperverted operation of their own understanding. Those whom they have assigned to the direction of their affairs, have stood with a pretty even front. If any one of them was withdrawn, many others entirely equal, have been ready to fill his place with as good abilities. A nation, composed of such materials, and free in all its members from distressing wants, furnishes hopeful implements for the interesting experiment of self-government; and we feel that we are acting under obligations not confined to the limits of our own society. It is impossible not to be sensible that we are acting for all mankind; that circumstances denied to others, but indulged to us, have imposed on us the duty of proving what is the degree of freedom and self-government in which a society may venture to leave its individual members. One passage, in the paper you enclosed me, must be corrected. It is the following, "and all say it was yourself more than any other individual, that planned and established it," i. e. the Constitution. I was in Europe when the Constitution was planned, and never saw it till after it was established. On receiving it I wrote strongly to Mr. Madison, urging the want of provision for the freedom of religion, freedom of the press, trial by jury, habeas corpus, the substitution of militia for a standing army, and an express reservation to the States of all rights not specifically granted to the Union. He accordingly moved in the first session of Congress for these amendments, which were agreed to and ratified by the States as they now stand. This is all the hand I had in what related to the Constitution. Our predecessors made it doubtful how far even these were of any value; for the very law which endangered your personal safety, as well as that which restrained the freedom of the press, were gross violations of them. However, it is still certain that though written constitutions may be violated in moments of passion or delusion, yet they furnish a text to which those who are watchful may again rally and recall the people; they fix too for the people the principles of their political creed. We shall all absent ourselves from this place during the sickly season; say from about the 22d of July to the last of September. Should your curiosity lead you hither either before or after that interval, I shall be very happy to receive you, and shall claim you as my guest. I wish the advantages of a mild over a winter climate had been tried for you before you were located where you are. I have ever considered this as a public as well as personal misfortune. The choice you made of our country for your asylum was honorable to it; and I lament that for the sake of your happiness and health its most benign climates were not selected. Certainly it is a truth that climate is one of the sources of the greatest sensual enjoyment. I received in due time the letter of April 10th referred to in your last, with the pamphlet it enclosed, which I read with the pleasure I do everything from you. Accept assurances of my highest veneration and respect.