Полная версия

Полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 3 (of 9)

Our Indian expeditions have proved successful. As yet, however, they have not led to peace. Mr. Hammond has lately arrived here as Minister Plenipotentiary from the court of London, and we propose to name one to that court in return. Congress will probably establish the ratio of representation by a bill now before them, at one representative for every thirty thousand inhabitants. Besides the newspapers, as usual, you will receive herewith the census lately taken, by towns and counties as well as by States.

I am, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO MR. HUMPHREYS

Philadelphia, November 29, 1791.Dear Sir,—My last to you was of August 23, acknowledging the receipt of your Nos. 19, 21, and 22. Since that, I have received from 23 to 33 inclusive. In mine, I informed you I was about setting out for Virginia, and consequently should not write to you till my return. This opportunity, by Captain Wicks, is the first since my return.

The party which had gone, at the date of my last, against the Indians north of the Ohio, were commanded by General Wilkinson, and were as successful as the first, having killed and taken about eighty persons, burnt some towns, and lost, I believe, not a man. As yet, however, it has not produced peace. A very formidable insurrection of the negroes in French St. Domingo has taken place. From thirty to fifty thousand are said to be in arms. They have sent here for aids of military stores and provisions, which we furnish just as far as the French minister here approves. Mr. Hammond is arrived here as Minister Plenipotentiary from Great Britain, and we are about sending one to that court from hence. The census, particularly as to each part of every State, is now in the press; if done in time for this conveyance, it shall be forwarded. The Legislature have before them a bill for allowing one representative for every thirty thousand persons, which has passed the Representatives, and is now with the Senate. Some late inquiries into the state of our domestic manufactories give a very flattering result. Their extent is great and growing through all the States. Some manufactories on a large scale are under contemplation. As to the article of Etrennes inquired after in one of your letters, it was under consideration in the first instance, when it was submitted to the President, to decide on the articles of account which should be allowed the foreign ministers in addition to their salary; and this article was excluded, as everything was meant to be which was not in the particular enumeration I gave you. With respect to foreign newspapers, I receive those of Amsterdam, France, and London so regularly, and so early, that I will not trouble you for any of them; but I will thank you for those of Lisbon and Madrid, and in your letters to give me all the information you can of Spanish affairs, as I have never yet received but one letter from Mr. Carmichael, which you I believe brought from Madrid. You will receive with this a pamphlet by Mr. Coxe in answer to Lord Sheffield, Freneau and Fenn's papers. I am, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO DANIEL SMITH, ESQ

Philadelphia, November 29, 1791.Sir,—I have to acknowledge the receipt of your favors of September 1 and October 4, together with the report of the Executive proceedings in the South-Western government from March 1 to July 26.

In answer to that part of yours of September 1 on the subject of a seal for the use of that government, I think it extremely proper and necessary, and that one should be provided at public expense.

The opposition made by Governor Blount and yourself to all attempts by citizens of the United States to settle within the Indian lines without authority from the General Government, is approved, and should be continued.

There being a prospect that Congress, who have now the Post office bill before them, will establish a post from Richmond to Stanton, and continue it thence towards the South-West government a good distance, if not nearly to it, our future correspondence will be more easy, quick, and certain. I am, with great esteem, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

Philadelphia, December 5, 1791.Dear Sir,—The enclosed memorial from the British minister, on the case of Thomas Pagan, containing a complaint of injustice in the dispensations of law by the courts of Massachusetts, to a British subject, the President approves of my referring it to you, to report thereon your opinion of the proceedings, and whether anything, and what, can or ought to be done by the government in consequence thereof.

I am, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

The Memorial of the British MinisterThe undersigned, his Britannic Majesty's Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States of America, has the honor of laying before the Secretary of State, the following brief abstract of the case of Thomas Pagan, a subject of his Britannic Majesty, now confined in the prison of Boston, under an execution issued against him out of the Supreme judicial court of Massachusetts Bay. To this abstract, the undersigned has taken the liberty of annexing some observations, which naturally arise out of the statement of the transaction, and which may perhaps tend to throw some small degree of light on the general merits of the case.

In the late war, Thomas Pagan was agent for, and part owner of a privateer called the Industry, which, on the 25th of March, 1783, off Cape Ann, captured a brigantine called the Thomas, belonging to Mr. Stephen Hooper, of Newport. The brigantine and cargo were libelled in the court of vice-admiralty in Nova Scotia, and that court ordered the prize to be restored. An appeal was, however, moved for by the captors, and regularly prosecuted in England before the Lords of Appeals for prize causes, who, in February, 1790, reversed the decree of the vice-admiralty court of Nova Scotia, and condemned the brigantine and cargo as good and lawful prize.

In December, 1788, a judgment was obtained by Stephen Hooper in the court of common pleas for the county of Essex, in Massachusetts, against Thomas Pagan, for three thousand five hundred pounds lawful money, for money had and received to the plaintiff's use. An appeal was brought thereon in May, 1789, to the Supreme judicial court of the commonwealth of Massachusetts, held at Ipswich, for the county of Essex, and on the 16th of June, 1789, a verdict was found for Mr. Hooper, and damages were assessed at three thousand and nine pounds two shillings and ten pence, which sum is "for the vessel called the brigantine Thomas, her cargo and every article found on board." After this verdict, and before entering the judgment, Mr. Pagan moved for a new trial, suggesting that the verdict was against law; because the merits of the case originated in a question, whether a certain brigantine called the Thomas, with her cargo, taken on the high seas by a private ship of war called the Industry, was prize or no prize, and that the court had no authority to give judgment in a cause where the point of a resulting or implied promise arose upon a question of this sort. The supreme judicial court refused this motion for a new trial, because it appeared to the court, that in order to a legal decision it is not necessary to inquire whether this prize and her cargo were prize or no prize, and because the case did not, in their opinion, involve a question relative to any matter or thing necessarily consequent upon the capture thereof: it was therefore considered by the court, that Hooper should receive of Pagan three thousand and nine pounds two shillings and ten pence lawful money, damages: and taxed costs, sixteen pounds two shillings and ten pence. From this judgment, Pagan claimed an appeal to the supreme judicial court of the United States of America, for these reasons: that the judgment was given in an action brought by Hooper, who is, and at the time of commencing the action was, a citizen of the commonwealth of Massachusetts, one of the United States, against Pagan, who, at the time when the action was commenced, was, and ever since has been, a subject of the King of Great Britain, residing in and inhabiting his province of New Brunswick. This claim of an appeal was not allowed, because it was considered by the court, that this court was the supreme judicial court of the commonwealth of Massachusetts, from whose judgment there is no appeal; and further, because there does not exist any such court within the United States of America as that to which Pagan has claimed an appeal from the judgment of this court. Thereupon, execution issued against Pagan on the 9th of October, 1789, and he has been confined in Boston prison ever since.

It is to be observed, that in August, 1789, Mr. Pagan petitioned the supreme judicial court of Massachusetts for a new trial, and after hearing the arguments of counsel, a new trial was refused. On the 1st of January, 1791, his Britannic Majesty's consul at Boston applied for redress on behalf of Mr. Pagan, to the Governor of Massachusetts Bay, who, in his letter of the 28th of January, 1791, was pleased to recommend this matter to the serious attention of the Senate and House of Representatives of that State. On the 14th of February, 1791, the British consul memorialized the Senate and House of Representatives on this subject. On the 22d of February, a committee of both Houses reported a resolution, that the memorial of the consul and message from the Governor, with all the papers, be referred to the consideration of the justices of the supreme judicial court, who were directed, as far as may be, to examine into and consider the circumstances of the case, and if they found that by the force and effect allowed by the law of nations to foreign admiralty jurisdictions, &c., Hooper ought not to have recovered judgment against Pagan, the court was authorized to grant a review of the action. On the 13th of June, 1791, the British consul again represented to the Senate and House of Representatives, that the justices of the supreme judicial court had not been pleased to signify their decision on this subject, referred to them by the resolution of the 22d of February. This representation was considered by a committee of the Senate and of the House of Representatives, who concluded that one of them should make inquiry of some of the judges to know their determination, and upon being informed that the judges intended to give their opinion, with their reasons, in writing, the committee would not proceed any further in the business. On the 27th of June, 1791, Mr. Pagan's counsel moved the justices of the supreme judicial court for their opinion in the case of Hooper and Pagan, referred to their consideration by the resolve of the General Court, founded on the British consul's memorial. Chief Justice and Justice Dana being absent, Justice Paine delivered it as the unanimous opinion of the judges absent as well as present, that Pagan was not entitled to a new trial for any of the causes mentioned in the said resolve, and added, "that the court intended to put their opinions upon paper, and to file them in the cause: that the sickness of two of the court had hitherto prevented it, but that it would soon be done."

It is somewhat remarkable, that the supreme judicial court of Massachusetts Bay, should allege that this case did not necessarily involve a question relative to prize or no prize, when the very jury to whom the court referred the decision of the case established the fact; their verdict was for three thousand and nine pounds two shillings and ten pence, damages, which sum is for the vessel called the brigantine Thomas, her cargo, and everything found on board. Hence it is evident, that the case did involve a question of prize or no prize, and having received a formal decision by the only court competent to take cognizance thereof, (viz. the high court of appeals for prize causes in England,) everything that at all related to the property in question, or to the legality of the capture, was thereby finally determined. The legality of the capture being confirmed by the high court of appeals in England, cannot consistently with the principles of the law of nations be discussed in a foreign court of law, or at least, if a foreign court of common law is, by any local regulations, deemed competent to interfere in matters relating to captures, the decisions of admiralty courts or courts of appeal, should be received and taken as conclusive evidence of the legality or illegality of captures. By such decisions, property is either adjudged to the captors or restored to the owners; if adjudged to the captors, they obtain a permanent property in the captured goods acquired by the rights of war, and this principle originates in the wisdom of nations, and is calculated to prevent endless litigation.

The proceedings of the supreme judicial court of Massachusetts Bay, are in direct violation of the rules and usages that have been universally practised among nations in the determination of the validity of captures, and of all collateral questions that may have reference thereto. The General Court of Massachusetts Bay, among other things, kept this point in view, when they referred the case of Mr. Pagan to the consideration of the justices of the supreme judicial court, and authorized the court to grant a review of the action, if it should be found that by the force and effect allowed by the law of nations to foreign admiralty jurisdictions, Mr. Hooper ought not to have recovered judgment against Mr. Pagan. But the supreme judicial court have not only evaded this material consideration, upon which the whole question incontestibly turns, but have assumed a fact in direct contradiction to the truth of the case, viz. that the case did not involve a question of prize or no prize. Moreover, they have denied Mr. Pagan the benefit of appeal to that court which is competent to decide on the force of treaties, and which court, by the constitution of the United States, is declared to possess appellate jurisdiction both as to law and fact, in all cases of controversy between citizens of the United States and subjects of foreign countries, to which class this case is peculiarly and strictly to be referred.

From the foregoing abstract of the case of Thomas Pagan, it appears that he is now detained in prison, in Boston, in consequence of a judgment given by a court which is not competent to decide upon his case, or which, if competent, refused to admit the only evidence that ought to have given jurisdiction, and that he is denied the means of appealing to the highest court of judicature known in these States, which exists in the very organization of the constitution of the United States, and is declared to possess appellate jurisdiction in all cases of a nature similar to this.

For these reasons, the undersigned begs leave respectfully to submit the whole matter to the consideration of the Secretary of State, and to request him to take such measures as may appear to him the best adapted for the purpose of obtaining for the said Thomas Pagan, such speedy and effectual redress as his case may seem to require.

George Hammond.Philadelphia, November 26, 1791.

TO MR. MCALISTER

Philadelphia, December 22, 1791.Sir,—I am favored with yours of the 1st of November, and recollect with pleasure our acquaintance in Virginia. With respect to the schools of Europe, my mind is perfectly made up, and on full enquiry. The best in the world is Edinburgh. Latterly, too, the spirit of republicanism has become that of the students in general, and of the younger professors; so on that account also it is eligible for an American. On the continent of Europe, no place is comparable to Geneva. The sciences are there more modernized than anywhere else. There, too, the spirit of republicanism is strong with the body of the inhabitants: but that of aristocracy is strong also with a particular class; so that it is of some consequence to attend to the class of society in which a youth is made to move. It is a cheap place. Of all these particulars Mr. Kinloch and Mr. Huger, of South Carolina, can give you the best account, as they were educated there, and the latter is lately from thence. I have the honor to be, with great esteem, Sir, your most obedient humble servant.

TO MR. STUART

Philadelphia, December 23, 1791.Dear Sir,—I received duly your favor of October 22, and should have answered it by the gentleman who delivered it, but that he left town before I knew of it.

That it is really important to provide a constitution for our State cannot be doubted: as little can it be doubted that the ordinance called by that name has important defects. But before we attempt it, we should endeavor to be as certain as is practicable that in the attempt we should not make bad worse. I have understood that Mr. Henry has always been opposed to this undertaking; and I confess that I consider his talents and influence such as that, were it decided that we should call a convention for the purpose of amending, I should fear he might induce that convention either to fix the thing as at present, or change it for the worse. Would it not therefore be well that means should be adopted for coming at his ideas of the changes he would agree to, and for communicating to him those which we should propose? Perhaps he might find ours not so distant from his, but that some mutual sacrifices might bring them together.

I shall hazard my own ideas to you as hastily as my business obliges me. I wish to preserve the line drawn by the federal constitution between the general and particular governments as it stands at present, and to take every prudent means of preventing either from stepping over it. Though the experiment has not yet had a long enough course to show us from which quarter encroachments are most to be feared, yet it is easy to foresee, from the nature of things, that the encroachments of the State governments will tend to an excess of liberty which will correct itself, (as in the late instance,) while those of the general government will tend to monarchy, which will fortify itself from day to day, instead of working its own cure, as all experience shows. I would rather be exposed to the inconveniences attending too much liberty, than those attending too small a degree of it. Then it is important to strengthen the State governments; and as this cannot be done by any change in the federal constitution, (for the preservation of that is all we need contend for,) it must be done by the States themselves, erecting such barriers at the constitutional line as cannot be surmounted either by themselves or by the general government. The only barrier in their power is a wise government. A weak one will lose ground in every contest. To obtain a wise and an able government, I consider the following changes as important. Render the legislature a desirable station by lessening the number of representatives (say to 100) and lengthening somewhat their term, and proportion them equally among the electors. Adopt also a better mode of appointing senators. Render the Executive a more desirable post to men of abilities by making it more independent of the legislature. To wit, let him be chosen by other electors, for a longer time, and ineligible forever after. Responsibility is a tremendous engine in a free government. Let him feel the whole weight of it then, by taking away the shelter of his executive council. Experience both ways has already established the superiority of this measure. Render the judiciary respectable by every possible means, to wit, firm tenure in office, competent salaries, and reduction of their numbers. Men of high learning and abilities are few in every country; and by taking in those who are not so, the able part of the body have their hands tied by the unable. This branch of the government will have the weight of the conflict on their hands, because they will be the last appeal of reason. These are my general ideas of amendments; but, preserving the ends, I should be flexible and conciliatory as to the means. You ask whether Mr. Madison and myself could attend on a convention which should be called? Mr. Madison's engagements as a member of Congress will probably be from October to March or April in every year. Mine are constant while I hold my office, and my attendance would be very unimportant. Were it otherwise, my office should not stand in the way of it. I am, with great and sincere esteem, dear Sir, your friend and servant.

TO THE PRESIDENT

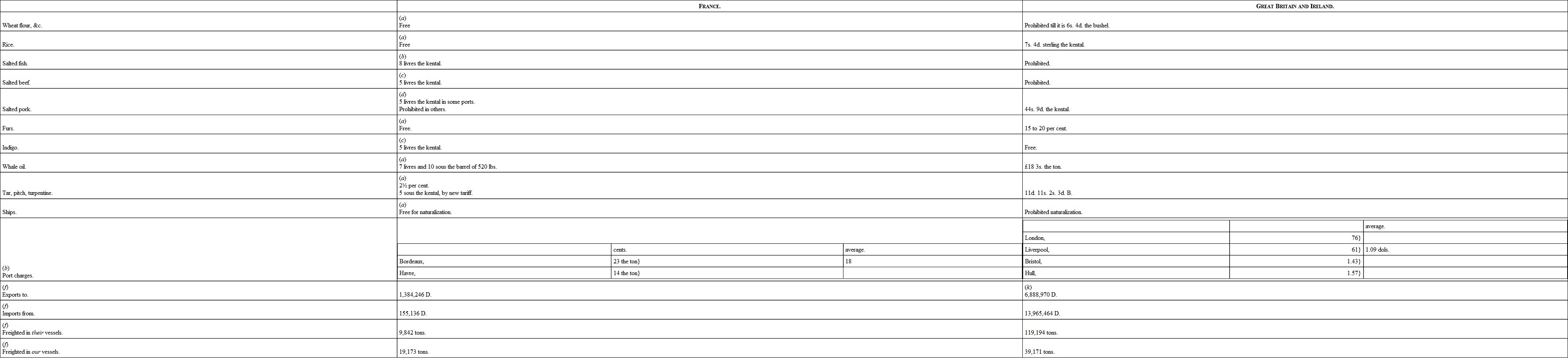

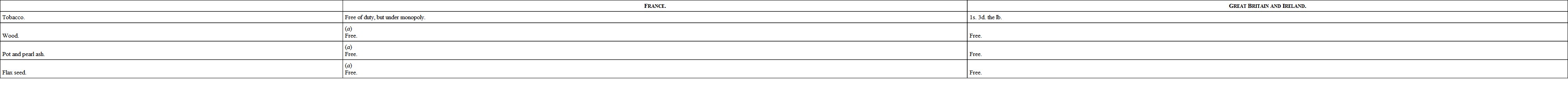

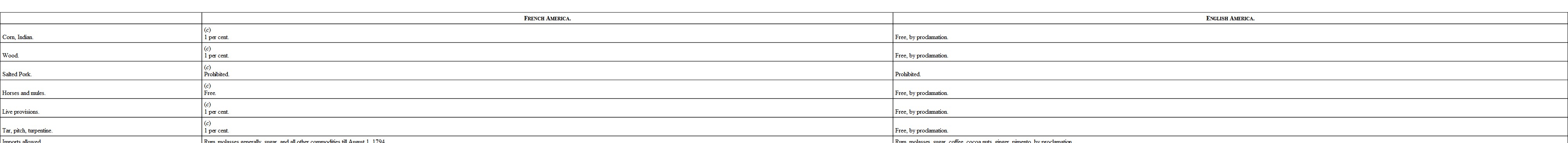

Philadelphia, December 23, 1791.Sir,—As the conditions of our commerce with the French and British dominions are important, and a moment seems to be approaching when it may be useful that both should be accurately understood, I have thrown a representation of them into the form of a table, showing at one view how the principal articles interesting to our agriculture and navigation, stand in the European and American dominions of these two powers. As to so much of it as respects France, I have cited under every article the law on which it depends; which laws, from 1784 downwards, are in my possession.

Port charges are so different, according to the size of the vessel and the dexterity of the captain, that an examination of a greater number of port bills might, perhaps, produce a different result. I can only say, that that expressed in the table is fairly drawn from such bills as I could readily get access to, and that I have no reason to suppose it varies much from the truth, nor on which side the variation would lie. Still, I cannot make myself responsible for this article. The authorities cited will vouch the rest.

I have the honor to be, with the most perfect respect and attachment, Sir, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

Footing of the Commerce of the United States with France and England, and with the French and English American Colonies.

The following articles being on an equal footing in both countries, are thrown together.

(a) By Arret of December the 29th, 1787.

(b) By Arret of 1763.

(c) By Arret of August the 30th, 1784.

(d) By Arret of 1788.

(e) By Arret of 1760.

(f) Taken from the Custom House returns of the United States.

(g) There is a general law of France prohibiting foreign flour in their islands, with a suspending power to their Governors, in cases of necessity. An Arret of May the 9th, 1789, by their Governor, makes it free till August, 1794; and in fact it is generally free there.

(h) The Arret of September the 18th, 1785, gave a premium of ten livres the kental, on fish brought in their own bottoms, for five years, so that the law expired September the 18th, 1790. Another Arret, passed a week after, laid a duty of five livres the kental, on fish brought in foreign vessels, to raise money for the premium before mentioned. The last Arret was not limited in time; yet seems to be understood as only commensurate with the other. Accordingly, an Arret of May the 9th, 1789, has made fish in foreign bottoms liable to three livres the kental only till August the 1st, 1794.

(i) The port charges are estimated from bills collected from the merchants of Philadelphia. They are different in different ports of the same country, and different in the same ports on vessels of different sizes. Where I had several bills of the same port, I averaged them together. The dollar is rated at 4s. 4½d. sterling in England, at 6s. 8d. in the British West Indies, and five livres twelve sous in France, and at eight livres five sous in the French West Indies.

Several articles stated to be free in France, do in fact pay one-eighth of a per cent., which was retained merely to oblige an entry to be made in their Custom House books. In like manner, several of the articles stated to be free in England, do, in fact, pay a light duty. The English duties are taken from the book of rates.