Полная версия

Полная версияThe Writings of Thomas Jefferson, Vol. 1 (of 9)

Salt. I do not know where the northern States supplied themselves with salt, but the southern ones took great quantities from Portugal.

Cotton and Wool. The southern States will take manufactures of both: the northern will take both the manufactures and raw materials.

East India goods of every kind. Philadelphia and New York have begun trade to the East Indies. Perhaps Boston may follow their example. But their importations will be sold only to the country adjacent to them. For a long time to come, the States south of the Delaware will not engage in a direct commerce with the East Indies. They neither have, nor will have ships or seamen for their other commerce: nor will they buy East India goods of the northern States. Experience shows that the States never bought foreign good of one another. The reasons are, that they would, in so doing, pay double freight and charges; and again, that they would have to pay mostly in cash, what they could obtain for commodities in Europe. I know that the American merchants have looked, with some anxiety, to the arrangements to be taken with Portugal, in expectation that they could, through her, get their East India articles on better and more convenient terms; and I am of opinion, Portugal will come in for a good share of this traffic with the southern States, if they facilitate our payments.

Coffee. Can they not furnish us with this article from Brazil?

Sugar. The Brazil sugars are esteemed, with us, more than any other.

Chocolate. This article, when ready made, as also the cocoa, becomes so soon rancid, and the difficulties of getting in fresh have been so great in America, that its use has spread but little. The way to increase its consumption would be, to permit it to be brought to us immediately from the country of its growth. By getting it good in quality, and cheap in price, the superiority of the article, both for health and nourishment, will soon give it the same preference over tea and coffee in America, which it has in Spain, where they can get it by a single voyage, and, of course, while it is sweet. The use of the sugars, coffee, and cotton of Brazil, would also be much extended by a similar indulgence.

Ginger and spices from the Brazils, if they had the advantage of a direct transportation, might take place of the same articles from the East Indies.

Ginseng. We can furnish them with enough to supply their whole demand for the East Indies.

They should be prepared to expect, that in the beginning of this commerce, more money will be taken by us, than after awhile. The reasons are, that our heavy debt to Great Britain must be paid, before we shall be masters of our own returns; and again, that habits of using particular things are produced only by time and practice.

That as little time as possible may be lost in this negotiation, I will communicate to you, at once, my sentiments as to the alterations in the draught sent them, which will probably be proposed by them, or which ought to be proposed by us, noting only those articles.

Article 3. They will probably restrain us to their dominions in Europe. We must expressly include the Azores, Madeiras, and Cape de Verd islands, some of which are deemed to be in Africa. We should also contend for an access to their possessions in America, according to the gradation in the 2d article of our instructions of May the 7th, 1784. But if we can obtain it in no one of these forms, I am of opinion we should give it up.

Article 4. This should be put into the form we gave it, in the draught sent you by Dr. Franklin and myself, for Great Britain. I think we had not reformed this article, when we sent our draught to Portugal. You know the Confederation renders the reformation absolutely necessary; a circumstance which had escaped us at first.

Article 9. Add, from the British draught, the clause about wrecks.

Article 13. The passage "nevertheless," &c., to run as in the British draught.

Article 18. After the word "accident," insert "or wanting supplies of provisions or other refreshments." And again, instead of "take refuge," insert "come," and after "of the other" insert "in any part of the world." The object of this is to obtain leave for our whaling vessels to refit and refresh on the coast of the Brazils; an object of immense importance to that class of our vessels. We must acquiesce under such modifications as they may think necessary, for regulating this indulgence, in hopes to lessen them in time, and to get a pied a terre in that country.

Article 19. Can we get this extended to the Brazils? It would be precious in case of a war with Spain.

Article 23. Between "places" and "whose," insert "and in general, all others," as in the British draught.

Article 24. For "necessaries," substitute "comforts."

Article 25. Add "but if any such consuls shall exercise commerce," &c., as in the British draught.

We should give to Congress as early notice as possible of the re-institution of this negotiation; because, in a letter by a gentleman who sailed from Havre, the 10th instant, I communicated to them the answer of the Portuguese minister, through the ambassador here, which I sent to you. They may, in consequence, be making other arrangements which might do injury. The little time which now remains, of the continuance of our commissions, should also be used with the Chevalier de Pinto, to hasten the movements of his court.

But all these preparations for trade with Portugal will fail in their effect, unless the depredations of the Algerines can be prevented. I am far from confiding in the measures taken for this purpose. Very possibly war must be recurred to. Portugal is at war with them. Suppose the Chevalier de Pinto was to be sounded on the subject of an union of force, and even a stipulation for contributing, each, a certain force, to be kept in constant cruise. Such a league once begun, other nations would drop into it, one by one. If he should seem to approve it, it might then be suggested to Congress, who, if they should be forced to try the measure of war, would doubtless be glad of such an ally. As the Portuguese negotiation should be hastened, I suppose our communications must often be trusted to the post, availing ourselves of the cover of our cypher.

I am, with sincere esteem, dear Sir, your friend and servant.

TO COLONEL HUMPHREYS

Paris, December 4, 1785.Dear Sir,—I enclose you a letter from Gatteaux, observing that there will be an anachronism, if, in making a medal to commemorate the victory of Saratoga, he puts on General Gates the insignia of the Cincinnati, which did not exist at that date. I wrote him, in answer, that I thought so too, but that you had the direction of the business; that you were now in London; that I would write to you, and probably should have an answer within a fortnight; and, that in the meantime, he could be employed on other parts of the die. I supposed you might not have observed, on the print of General Gates, the insignia of the Cincinnati, or did not mean that that particular should be copied. Another reason against it strikes me. Congress have studiously avoided giving to the public their sense of this institution. Should medals be prepared, to be presented from them to certain officers, and bearing on them the insignia of the order, as the presenting them would involve an approbation of the institution, a previous question would be forced on them, whether they would present these medals? I am of opinion it would be very disagreeable to them to be placed under the necessity of making this declaration. Be so good as to let me know your wishes on this subject, by the first post.

Mr. Short has been sick ever since you left us. Nothing new has occurred here, since your departure. I imagine you have American news. If so, pray give us some. Present me affectionately to Mr. Adams and the ladies, and to Colonel Smith; and be assured of the esteem with which I am, dear Sir, your friend and servant.

TO JOHN ADAMS

Paris, December 10, 1785.Dear Sir,—On the arrival of Mr. Boylston, I carried him to the Marquis de La Fayette, who received from him communications of his object. This was to get a remission of the duties on his cargo of oil, and he was willing to propose a future contract. I suggested, however, to the Marquis, when we were alone, that instead of wasting our efforts on individual applications, we had better take up the subject on general ground, and whatever could be obtained, let it be common to all. He concurred with me. As the jealousy of office between ministers does not permit me to apply immediately to the one in whose department this was, the Marquis's agency was used. The result was, to put us on the footing of the Hanseatic towns, as to whale oil, and to reduce the duties to eleven livres and five sols for five hundred and twenty pounds, French, which is very nearly two livres on the English hundred weight, or about a guinea and a half the ton. But the oil must be brought in American or French ships, and the indulgence is limited to one year. However, as to this, I expressed to Count de Vergennes my hopes that it would be continued; and should a doubt arise, I should propose, at the proper time, to claim it under the treaty, on the footing gentis amicissimæ. After all, I believe Mr. Boylston has failed of selling to Sangrain, and, from what I learn, through a little too much hastiness of temper. Perhaps they may yet come together, or he may sell to somebody else.

When the general matter was thus arranged, a Mr. Barrett arrived here from Boston, with letters of recommendation from Governor Bowdoin, Cushing, and others. His errand was, to get the whale business here put on a general bottom, instead of the particular one, which had been settled, you know, the last year, for a special company. We told him what was done. He thinks it will answer, and proposes to settle at L'Orient, for conducting the sales of the oil, and the returns. I hope, therefore, that this matter is tolerably well fixed, as far as the consumption of this country goes. I know not, as yet, to what amount that is; but shall endeavor to find out how much they consume, and how much they furnish themselves. I propose to Mr. Barrett, that he should induce either his State or individuals to send a sufficient number of boxes of the spermaceti candle, to give one to every leading house in Paris; I mean to those who lead the ton; and, at the same time, to deposit a quantity for sale here, and advertise them in the petites affiches. I have written to Mr. Carmichael, to know on what footing the use and introduction of the whale oil is there, or can be placed.

I have the honor to be, with very sincere esteem, dear Sir, your most obedient humble servant.

TO THE GOVERNOR OF GEORGIA

Paris, December 22, 1785.Sir,—The death of the late General Oglethorpe, who had considerable possessions in Georgia, has given rise, as we understand, to questions whether those possessions have become the property of the State, or have been transferred by his will to his widow, or descended on the nearest heir capable in law of taking them. In the latter case, the Chevalier de Mezieres, a subject of France, stands foremost, as being made capable of the inheritance by the treaty between this country and the United States. Under the regal government, it was the practice with us, when lands passed to the crown by escheat or forfeiture, to grant them to such relation of the party, as stood on the fairest ground. This was even a chartered right in some of the States. The practice has been continued among them, as deeming that the late Revolution should, in no instance, abridge the rights of the people. Should this have been the practice in the State of Georgia, or should they, in any instance, think proper to admit it, I am persuaded none will arise, in which it would be more expedient to do it, than in the present, and that no person's expectations should be fairer than those of the Chevalier de Mezieres. He is the nephew of General Oglethorpe, he is of singular personal merit, an officer of rank, of high connections, and patronized by the ministers. His case has drawn their attention, and seems to be considered as protected by the treaty of alliance, and as presenting a trial of our regard to that. Should these lands be considered as having passed to the State, I take the liberty of recommending him to the legislature of Georgia, as worthy of their generosity, and as presenting an opportunity of proving the favorable dispositions which exist throughout America, towards the subjects of this country, and an opportunity too, which will probably be known and noted here.

In the several views, therefore, of personal merit, justice, generosity and policy, I presume to recommend the Chevalier de Mezieres, and his interests, to the notice and patronage of your Excellency, whom the choice of your country has sufficiently marked, as possessing the dispositions, while it has, at the same time, given you the power, to befriend just claims. The Chevalier de Mezieres will pass over to Georgia in the ensuing spring; but, should he find an opportunity, he will probably forward this letter sooner. I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the most profound respect, your Excellency's most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO THE GEORGIA DELEGATES IN CONGRESS

Paris, December 22, 1785.Gentlemen,—By my despatch to Mr. Jay, which accompanies this, you will perceive that the claims of the Chevalier de Mezieres, nephew to the late General Oglethorpe, to his possessions within your State, have attracted the attention of the ministry here; and that, considering them as protected by their treaty with us, they have viewed as derogatory of that, the doubts which have been expressed on the subject. I have thought it best to present to them those claims in the least favorable point of view, to lessen, as much as possible, the ill effects of a disappointment; but I think it my duty to ask your notice and patronage of this case as one whose decision will have an effect on the general interests of the Union.

The Chevalier de Mezieres is nephew to General Oglethorpe; he is a person of great estimation, powerfully related and protected. His interests are espoused by those whom it is our interest to gratify. I will take the liberty, therefore, of soliciting your recommendations of him to the generosity of your legislature, and to the patronage and good offices of your friends, whose efforts, though in a private case, will do a public good. The pecuniary advantages of confiscation, in this instance, cannot compensate its ill effects. It is difficult to make foreigners understand those legal distinctions between the effects of forfeiture, of escheat, and of conveyance, on which the professors of the law might build their opinions in this case. They can see only the outlines of the case; to wit, the death of a possessor of lands lying within the United States, leaving an heir in France, and the State claiming those lands in opposition to the heir. An individual, thinking himself injured, makes more noise than a State. Perhaps, too, in every case which either party to a treaty thinks to be within its provisions, it is better not to weigh the syllables and letters of the treaty, but to show that gratitude and affection render that appeal unnecessary. I take the freedom, therefore, of submitting to your wisdom, the motives which present themselves in favor of a grant to the Chevalier de Mezieres, and the expediency of urging them on your State, as far as you may think proper.

I have the honor to be, with sentiments of the highest respect, Gentlemen, your most obedient, and most humble servant.

TO JOHN ADAMS

Paris, December 27, 1785.Dear Sir,—Your favors of the 13th and 20th, were put in my hands to-day. This will be delivered you by Mr. Dalrymple, secretary to the legation of Mr. Crawford. I do not know whether you were acquainted with him here. He is a young man of learning and candor, and exhibits a phenomenon I never before met with, that is, a republican born on the north side of the Tweed.

You have been consulted in the case of the Chevalier de Mezieres, nephew to General Oglethorpe, and are understood to have given an opinion derogatory of our treaty with France. I was also consulted, and understood in the same way. I was of opinion the Chevalier had no right to the estate, and as he had determined the treaty gave him a right, I suppose he made the inference for me, that the treaty was of no weight. The Count de Vergennes mentioned it to me in such a manner, that I found it was necessary to explain the case to him, and show him the treaty had nothing to do with it. I enclose you a copy of the explanation I delivered him.

Mr. Boylston sold his cargo to an agent of Monsieur Sangrain. He got for it fifty-five livres the hundred weight. I do not think that his being joined to a company here would contribute to its success. His capital is not wanting. Le Conteux has agreed that the merchants of Boston, sending whale oil here, may draw on him for a certain proportion of money, only giving such a time in their drafts, as will admit the actual arrival of the oil into a port of France, for his security. Upon these drafts, Mr. Barrett is satisfied they will be able to raise money, to make their purchases in America. The duty is seven livres and ten sols on the barrel of five hundred and twenty pounds, French, and ten sous on every livre, which raises it to eleven livres and five sols, the sum I mentioned to you. France uses between five and six millions of pounds' weight French, which is between three and four thousand tons, English. Their own fisheries do not furnish one million, and there is no probability of their improving. Sangrain purchases himself upwards of a million. He tells me our oil is better than the Dutch or English, because we make it fresh, whereas they cut up the whale, and bring it home to be made, so that it is, by that time, entered into fermentation. Mr. Barrett says, that fifty livres the hundred weight will pay the prime cost and duties, and leave a profit of sixteen per cent to the merchant. I hope that England will, within a year or two, be obliged to come here to buy whale oil for her lamps.

I like as little as you do to have the gift of appointments. I hope Congress will not transfer the appointment of their consuls to their ministers. But if they do, Portugal is more naturally under the superintendence of the minister at Madrid, and still more naturally under that of the minister at Lisbon, where it is clear they ought to have one. If all my hopes fail, the letters of Governor Bowdoin and Cushing, in favor of young Mr. Warren, and your more detailed testimony in his behalf, are not likely to be opposed by evidence of equal weight, in favor of any other. I think with you, too, that it is for the public interest to encourage sacrifices and services, by rewarding them, and that they should weigh to a certain point, in the decision between candidates.

I am sorry for the illness of the Chevalier Pinto. I think that treaty important; and the moment to urge it is that of a treaty between France and England.

Lambe, who left this place the 6th of November, was at Madrid the 10th of this month. Since his departure, Mr. Barclay has discovered that no copies of the full powers were furnished to himself, nor of course to Lambe. Colonel Franks has prepared copies, which I will endeavor to get, to send by this conveyance for your attestation; which you will be so good as to send back by the first safe conveyance, and I will forward them. Mr. Barclay and Colonel Franks being at this moment at St. Germain's, I am not sure of getting the papers in time to go by Mr. Dalrymple. In that case, I will send them by Mr. Bingham.

Be so good as to present me affectionately to Mrs. and Miss Adams, to Colonels Smith and Humphreys, and accept assurances of the esteem with which I am, dear Sir, your friend and servant.

TO F. HOPKINSON

Paris, January 3, 1786.Dear Sir,—I wrote you last, on the 25th of September. Since that, I have received yours of October the 25th, enclosing a duplicate of the last invented tongue for the harpsichord. The letter enclosing another of them, and accompanied by newspapers, which you mention in that of October the 25th, has never come to hand. I will embrace the first opportunity of sending you the crayons. Perhaps they may come with this, which I think to deliver to Mr. Bingham, who leaves us on Saturday, for London. If, on consulting him, I find the conveyance from London uncertain, you shall receive them by a Mr. Barrett, who goes from hence for New York, next month. You have not authorized me to try to avail you of the new tongue. Indeed, the ill success of my endeavors with the last does not promise much with this. However, I shall try. Houdon only stopped a moment, to deliver me your letter, so that I have not yet had an opportunity of asking his opinion of the improvement. I am glad you are pleased with his work. He is among the foremost, or, perhaps, the foremost artist in the world.

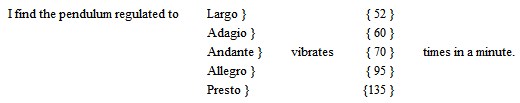

Turning to your Encyclopedie, Arts et Metiers, tome 3, part 1, page 393, you will find mentioned an instrument, invented by a Monsieur Renaudin, for determining the true time of the musical movements, largo, adagio, &c. I went to see it. He showed me his first invention; the price of the machine was twenty-five guineas; then his second, which he had been able to make for about half that sum. Both of these had a mainspring and a balance wheel, for their mover and regulator. The strokes were made by a small hammer. He then showed me his last, which is moved by a weight and regulated by a pendulum, and which cost only two guineas and a half. It presents, in front, a dial-plate like that of a clock, on which are arranged, in a circle, the words largo, adagio, andante, allegro, presto. The circle is moreover divided into fifty-two equal degrees. Largo is at 1, adagio at 11, andante at 22, allegro at 36, and presto at 46. Turning the index to any one of these, the pendulum (which is a string, with a ball hanging to it) shortens or lengthens, so that one of its vibrations gives you a crotchet for that movement. This instrument has been examined by the academy of music here, who are so well satisfied of its utility, that they have ordered all music which shall be printed here, in future, to have the movements numbered in correspondence with this plexi-chronometer. I need not tell you that the numbers between two movements, as between 22 and 36, give the quicker or slower degrees of the movements, such as the quick andante, or moderate allegro. The instrument is useful, but still it may be greatly simplified. I got him to make me one, and having fixed a pendulum vibrating seconds, I tried by that the vibrations of his pendulum, according to the several movements.

Every one, therefore, may make a chronometer adapted to his instrument.

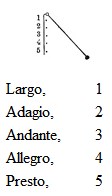

For a harpsichord, the following occurs to me.

In the wall of your chamber, over the instrument, drive five little brads, as 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, in the following manner. Take a string with a bob to it, of such length, as that hung on No. 1, it shall vibrate fifty-two times in a minute. Then proceed by trial to drive No. 2, at such a distance, that drawing the loop of the string to that, the part remaining between 1 and the bob, shall vibrate sixty times in a minute. Fix the third for seventy vibrations, &c.; the cord always hanging over No. 1, as the centre of vibration. A person, playing on the violin, may fix this on his music stand. A pendulum thrown into vibration, will continue in motion long enough to give you the time of your piece. I have been thus particular, on the supposition that you would fix one of these simple things for yourself.

You have heard often of the metal, called platina, to be found only in South America. It is insusceptible of rust, as gold and silver are, none of the acids affecting it, excepting the aqua regia. It also admits of as perfect a polish as the metal hitherto used for the specula of telescopes. These two properties had suggested to the Spaniards the substitution of it for that use. But the mines being closed up by the government, it is difficult to get the metal. The experiment has been lately tried here by the Abbé Rochon, (whom I formerly mentioned to Mr. Rittenhouse, as having discovered that lenses of certain natural crystals have two different and uncombined magnifying powers) and he thinks the polish as high as that of the metal heretofore used, and that it will never be injured by the air, a touch of the finger, &c. I examined it in a dull day, which did not admit a fair judgment of the strength of its reflection.