Полная версия:

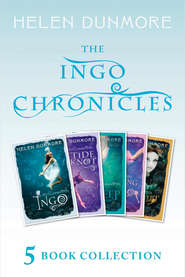

The Complete Ingo Chronicles: Ingo, The Tide Knot, The Deep, The Crossing of Ingo, Stormswept

“Me and Saph’ll go on down to the cove then, Mum, unless you need us here,” says Conor. “Sure you’ll be all right climbing down?”

“I can manage,” says Mum. “It’s not the climb down that worries me.” She makes herself smile and I know how afraid of the sea she still is. How hard she’s trying, because of Roger. “I’ve got to do it on my own.”

“Be careful. The rocks are slippery,” warns Conor. “Let me help you, Mum.”

“Do you think I don’t know by now what the sea can do?” asks Mum quietly. “You two go off now, and let me finish this in peace. I’ll see you down there later. Roger’ll be glad to show you the diving equipment, Con. He says there’s a starter diving course you can take, at the dive school in St Pirans. It’s just a week, to give you a taste of what diving’s like. He’s going to fix it up with that friend he told you about.”

As soon as we are out of the cottage, we start to run.

“Conor, they hate divers. Faro told me—”

“I know. Air People with air on their backs—”

“Taking Air into Ingo. Did Elvira tell you that as well?”

“Yeah.”

“And he’s going to the Bawns. He doesn’t know—”

“What about the Bawns? What doesn’t Roger know?”

“I’m not sure. But it’s something serious. Faro said there was something out at the Bawns so important that the whole of Ingo would defend it. He wouldn’t tell me what it was.”

“And Roger’s going to dive there. That’s all we need.”

Down the track, down the path, over the lip of the cliff, and down, down, hearts pounding, hands slippery with sweat, stumbling on loose stones and catching hold of the rock. Down and down, sliding on seaweed, jumping from rock to rock, past limpets and mussels and dead dogfish and dark damp crevices where the sun never goes and there are piles of driftwood and bleached rope and plastic net buoys.

And down on to the firm white sand. Everything is calm and sunny and beautiful. The sea is like a piece of wrinkled silk. The beach is empty. Little waves curl and flop on to the shore. We shield our eyes from the light and squint towards the rocks at the entrance of the cove. Nothing. No sign of a boat.

“They must be out there.”

“How long would it take to come round by boat from St Pirans?”

“I don’t know. Not that long. Roger’s boat has a powerful engine.”

“Maybe it’ll break down,” I say hopefully.

“It’s new. Anyway, dive boats usually carry back-up parts,” says Conor.

You can’t see the Bawns from here. The rocks at the mouth of the cove hide them. Maybe Roger and Gray are out there now, preparing to dive. They don’t know what the Bawns mean to the Mer. They’ll trespass without knowing what they’re doing, and all the force of Ingo will be against them.

“If only we had a boat,” mutters Conor.

“We’ve got to get out there somehow, before they do!”

“We can’t,” says Conor. “We’ll just have to wait. It’ll be OK, Sapphy. Roger knows what he’s doing. He’s a dive leader.”

“What’s that mean?”

“He’s got loads of experience. He’s passed exams and stuff. He’ll be all right.”

But Conor doesn’t sound as if he believes it, and nor do I.

“Conor, we can’t just stand here waiting. We’ve got to do something.”

“Swim?” asks Conor sarcastically. He knows as well as I do why we mustn’t swim out of the cove. We know how dangerous it is. There’s always the rip waiting to take you. The water’s deep and cold and wild, and a swimmer who gets swept away doesn’t last long.

“But I’ve got to do something, Conor. It’s my fault. It was me who told Faro about Roger.”

“You didn’t mean any harm.”

“I did. You don’t understand.” I pause, and think. Maybe, at the same time that I was telling Faro about Roger diving near the Bawns, Roger was telling Mum that she ought to think about letting us have Sadie. “I wanted Roger to get hurt,” I whisper. “Oh, Conor, why have I got so much badness in me?”

As I say these words a gull plunges, screaming, from the cliff. We both turn. It’s coming straight for us, diving, wings sleek against the air currents. Its beak is open. Down it comes, crying out in its fierce gull voice. It swerves above our heads, so close that my hair lifts in the wake of its claws. Up it soars, high into the blue, then it turns and positions itself for a second dive. Again it screams out in its wild language as it balances on the air. And down it comes again, passing my ear with a shriek.

“It’s trying to tell us something.”

“What?”

“If only I could understand it.”

But maybe… maybe… if I really try… I could make out what the gull is saying. It wants me to know, that’s why it’s diving so close. Here it comes again.

“I can’t hear what you’re saying,” I shout above the gull’s shrieks. “Please, please try to say it so that I can understand—”

The gull’s screams batter my ears again, but all I get from it is noise.

“Please try, please. I know you’re trying to tell me something important…”

And then it happens. I am through the skin of English, and into another language. Suddenly the new language is all around me. The jumble of wild shrieks changes to syllables, then words. The gull brakes in the air and hovers just above us. His wings beat furiously and his claws dig into the air for balance. He fixes me with a cold yellow eye.

“Go to Ingo. Go to Ingo NOW.”

And he spreads his wings and swoops low over the water, out to sea.

“He was going crazy about something, wasn’t he?” says Conor. “Wouldn’t it be great if we could understand what birds are saying.”

“He wants us to go into Ingo,” I say.

Conor stares. “You’re making it up.”

“You know I’m not. Look at me. Am I lying?”

Conor scrutinises me. At last he says reluctantly, “No. But you could be crazy too.”

“The gull said, Go to Ingo now.”

“Then it’s definitely mad. We can’t go into Ingo on our own.”

“I think we can. I think it’s the same as understanding what the gulls say. If you want to enough, you can. And as soon as we’re in Ingo we can get out to the Bawns. The rips won’t hurt us. You can’t drown when you’re in Ingo.”

“You could understand the gull, Saph. It just sounded like a gull screeching to me. I’ve only ever been in Ingo with Elvira. Holding her wrist all the time.”

“You mean… Do you mean that maybe I could get into Ingo without help from any of the Mer, but you couldn’t?”

Conor’s eyes flash with anger. “You don’t think I’d let you go into danger on your own, do you? If you go, Saph, I’m going too.”

Everything is turning around. All our lives it’s been Conor who does everything first and best. Riding a bike, riding a horse, swimming, surfing, going out in the boat with Dad, climbing to the top of the cliffs. I’ve always been coming along behind, with Conor turning back to help me. And now, for the first time, there’s something that’s easier for me than it is for Conor.

Granny Carne said that inheritances don’t come down equally, even to brother and sister. Powerful Mer blood, she said. I hope it’s powerful enough for both of us. If Conor comes into Ingo with me, it’s up to me to make sure that he’s safe.

“We’ll go together,” I say. “We’ll hold on to each other’s wrists, like we do with Faro and Elvira. Then we’ll be OK.”

“Sapphire, don’t be stupid,” says Conor. “How do you think we’re going to dive like that? You don’t have to pretend. I’m the one who’ll have to hold on. You could breathe on your own, couldn’t you? You told me.”

“Two are stronger than one,” I say. It’s what Mum always says, when she tells us to stick together. I know how hard it must be for Conor. He’s the older brother, I’m the little sister. But now he’s got to trust me. I’ve got to take us both into Ingo and bring us back safe. I think I can do it. I’m almost sure I can do it. But is “almost sure” good enough, when Conor’s going to be depending on me? I’ve got to. We have no choice.

“Yeah, two are stronger than one,” says Conor. “And if you let me drown, I’m telling Mum.”

We both laugh and it breaks the tension. I take a deep breath.

“I suppose we’d better—”

“Let’s go,” says Conor.

We walk forward over the sand. There’s the sea I’ve longed for, cool and transparent and calm. When I was up at Granny Carne’s cottage I felt as if I’d die if I didn’t get to the sea.

And here it is, and here I am. And I’m afraid. My hands are sticky with sweat and my heart bumps inside me so loudly that I’m sure Conor can hear it. I’ve been longing for Ingo so much, but now that I’m standing on the borderline I want to turn around and run until I’m back in the cottage with my duvet wrapped over my head. I feel sick and I can’t breathe properly.

Give up, says a voice in my head. Go back. You don’t even like Roger. Why risk your life and Conor’s to help him? You know how dangerous it is. Go home now. No one will blame you. No one will know. You’re only a child. Roger’s a grown man, he can take care of himself.

Yes. It’s true. It’s Roger’s fault for coming here. It’s not my responsibility. I can tell Conor that it’s too dangerous and I haven’t got the power to take him into Ingo. Nobody will ever know if it’s true or not.

But then I hear Granny Carne. Of course I can’t really hear her, but I remember her words so strongly that it’s like her voice speaking in my ear: You’ve got Mer blood in you, Sapphire. It’s come down to you from your ancestors. You can do it.

Granny Carne will know that I had a choice, and I went home. And Conor will know too. And most of all, I will always know, and I won’t be able to pretend to myself. I can try to help Roger or I can abandon him, and let him blunder into the Bawns with all of Ingo against him.

Roger tried to help me. We talked about Sadie in the kitchen and Roger understood about her. He told Mum he thought we were old enough and responsible enough to have a dog. Maybe Mum won’t ever let me have Sadie, but if she doesn’t, it’s not because Roger didn’t try.

I can try to help Roger, or not. The choice is mine.

As soon as I say these words to myself, the noise of blood rushing in my ears doesn’t frighten me so much. I’m not panicking any more. The choice is mine. I can make it.

I look around, and spot another gull on the rock where Faro sat the first time I saw him. The gull leans forward, watching us, neck outstretched and beak wide, the way gulls do when they’re warning you off their territory. This time I understand straight away.

“NOW!” shrieks the gull. “Go to Ingo NOW.”

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

Ingo is angry. We know it as soon as we are beneath the skin of the water, as soon as the pain of entering Ingo fades enough for us to notice anything else. Currents twist around us like a nest of snakes. The sea boils and bubbles. Down and down we go, spiralling, while white sand whirls around us, beaten by the underwater storm. The rage of the sea catches us and blows us before it like leaves in the wind.

“Look out!” says Conor. “Rocks!”

We’re being swept towards the black rocks that guard the entrance to the cove. Ingo can’t drown us, but it has other ways of destroying us if it wants to.

“Don’t hurt us,” I plead under my breath. “We haven’t come to harm you.”

The wicked spikes of the rock shoot past, less than a metre away. This time, Ingo has let us escape. We plunge into deep dark water, dragged by a current that lashes like a switchback. Down, down, down, deep into Ingo. Suddenly the current throws us off.

We’ve got to swim. I peer through the surging water, looking for some sign of the Bawns. Has the current carried us past them already? The water’s so dark and wild, so strong, that I don’t know if I can swim against it. I kick with all my strength, then kick again, but it’s like trying to swim in a dream. Conor tugs my wrist.

“Saph, you OK?”

I turn to him. “I’m fine,” I start to say, then realise that it’s Conor who doesn’t look right. There are blue shadows around his eyes and mouth, and his face is twisted with pain. His legs move feebly. But Conor is a brilliant swimmer, much better than me. What’s the matter with him? Why isn’t he swimming?

And then I know. Conor is not getting enough oxygen. Ingo won’t let him. He’s getting some oxygen through me, but only a little. Not enough.

“Conor, hold on to me! Hold tight.”

Conor’s grip on my wrist is weak. In a flash of terror I realise that I’m all he’s got, and I’m not strong enough. Not when Ingo is angry, and the waters are dark with danger. Not when we’re being whirled through the deep water like human rags inside a giant washing machine. I catch hold of Conor’s other wrist and try to find his pulse. It’s there, but it’s so hard to feel that I’m frightened. Conor’s fingers are slipping off my wrist.

“Conor! You’ve got to hold on!”

“M’OK, Saph. Tired.”

“Don’t try to swim. I’ll swim for both of us. Just keep still. Try to relax.”

Try to relax. You idiot. You brought him down here. You thought you had enough strength for two, and he believed you. It’s your fault, Sapphire, no one else’s.

“Can’t breathe,” mutters Conor.

Oh God, he mustn’t start trying to breathe. It’s dangerous. There’s no air here. Oxygen is flowing smoothly into my body, but not into Conor’s. He’s suffering, it’s hurting him. We’re so deep down, I’ll never get him to the surface in time. And even if I do, once we’re out of Ingo, the sea will drown us both—

“Conor, don’t try to breathe! You mustn’t!”

What can I do? How can I help him? We should never have come alone. If Faro was here – Faro would be strong enough to help—

“Faro!” I cry out with all my strength. “Faro!”

“Don’t, Saph. Faro won’t help. He’s with the Mer. He’s on their side.”

Conor’s eyes are dull, half shut. We cling to each other as the current spins us around and drags us through the wide mouth of our cove. Below us the floor of the sea falls away. Deep, dark, stormy water sweeps us along. I hold on to Conor with all my strength but he’s barely grasping me. His head falls back.

“Faro! Help us!”

I am sure Faro can hear me. I am sure he is there, just out of sight behind the tumult of the water. I know it. How can Faro let Conor suffer like this? Why won’t he come to us?

The cry of the gull flashes over my mind. He spoke to me, and I understood. Maybe I am using the wrong language to call Faro. Faro is Mer, not Air. Maybe I can find that other language, buried deep inside me. I found words before. Moryow… broder…

My ancestors had powerful Mer blood, I think fiercely. They passed their power down to me. It comes down from generation to generation, and it doesn’t weaken. I am human, but if Granny Carne’s right, I am also partly Mer. I can make Faro hear me. I must help Conor. Broder, broder…

I grasp Conor as tightly as I can. He’s not holding on to me any more. Maybe he can’t feel where I am. I’m going to lose him. He’s going to drift away, my Conor, down and down into Ingo until he’s lost. And I said I’d bring him back safe.

No. I’m not going to let it happen. If I have any power in Ingo, I’ll make Faro come to me.

I open my mouth. Strong salt water bubbles into it, stroking my tongue and my palate, filling my throat. If I can make words out of water, Faro will hear me.

In my head there are words I didn’t know that I knew. Say them, Sapphire. All you’ve got to do is speak. They fill my mouth. They echo in my ears. They pour out in strange syllables that I’ve never spoken before. It’s a new language that sounds like the oldest and most familiar language in the world, shaped out of salt and currents and tides.

“Faro, I ask you in the name of our ancestors to come to me now.”

The words echo more and more loudly, booming in my head, making waves of sound that are picked up by the water and carried away. Faro… in the name of our ancestors… Faro… Faro…

And he is here. Suddenly there on the other side of Conor, swimming alongside us, his hand closed tight around Conor’s wrist. As I watch, the blue fades from under Conor’s eyes and from around his mouth. Warm brown floods back into Conor’s skin. His eyes open, bright and alert. He looks around, as if he’s just woken up.

“Wow! This is like being inside a fantastic Jacuzzi, Saph!”

And suddenly it is. The violence of the sea isn’t terrifying any more. It’s like a huge, wild game. We twist and turn and plunge and dive. It’s like bodysurfing, but a million times better because we are part of the waves and free to go with them wherever we want. Like surfing in a world where the wave never breaks.

“Roger,” yells Conor as he balances with Faro on a surging rope of current. “We mustn’t forget Roger.”

“Roger? Who is Roger?” asks Faro, his voice smooth as silk. But I know he’s only pretending. He knows full well who Roger is.

“He’s a diver. I told you about him. But he doesn’t mean any harm. He doesn’t know what he’s doing.”

“You are talking Air to me now,” says Faro, his tail savagely slashing a cloud of bubbles. “It wasn’t Air talk that brought me here to help you. If I remember our ancestors, then so must you.”

“I do remember them.”

“You remember them when you want to, Sapphire. When you need them. Not when Ingo needs you. Your head is full of Air.”

“I wish you two would stop arguing,” says Conor. “We must be close to the Bawns now.”

“It’s all right, Con. They would never dive in this,” I say quickly. “It’s much too wild.”

“But it’s not wild on the surface,” says Faro. “It looks perfectly calm, up there. You’d never guess there was a storm in Ingo.” He grins at me, his face bright with malice. “Perfect diving conditions.”

“Don’t, Faro!”

Faro rolls to face me. “You are going to see something, my little hwoer.”

“I’m not your sister. Elvira’s your sister.”

“It’s just a figure of speech. Mer speech, that is. Look ahead. There are the Bawns.”

I would never have thought the Bawns would be so huge. They loom ahead of us like a mountain country. The part that you can see above the water is nothing compared to these underwater peaks and valleys. I thought the Bawns were just rocks, but that was an Air thought.

“You’re going to see something,” repeats Faro, pulling us forward.

We are in the shadow of the Bawns now. The surge of the sea is calmer. The water is clear and there is a strange light, like moonlight. Every detail shows: white glistening sand below us, scattered with shells and crab skeletons, sculptured rock, darting fish.

“This way. Quietly.”

We swim around a broad shoulder of rock then suddenly stop dead as Faro back-fins.

“There,” he says.

A plain of sand spreads out in front of us, protected by the mountain range of the Bawns. The wind dies. The surge of the sea fades to stillness. Here, the sea is as quiet as a garden at the end of a long summer day. And scattered on the plain of soft, glistening, rippled sand there are figures like ghosts, or dreams. I blink, believing they’ll disappear like shadows, but when I open my eyes the figures are still there. Bowed, bent, their hair as silver as the sand, they rest, half lying, half drifting in the still water.

“They are our wise ones,” says Faro. “They will die soon.”

As I watch, a gentle current lifts a lock of silver hair from one of the figures, and lets it fall back, softly, against the bowed shoulders.

“Nothing can hurt them. Nothing comes near them,” says Faro. “Look. The seals guard them.”

It’s true. Watchful and powerful, grey seals patrol the edges of the plain. They swim to and fro, along a borderline that’s invisible to me, turning their heads to scan the water and the mountain range of rock that rises behind us.

“They’ve seen us,” says Faro. He raises both hands, palms flat and outwards, saluting the seals. “We can come this far,” he adds, “but if we tried to go down to the plain, the seals would attack us.”

“But you’re Mer. Why would they attack you?”

“I’m not ready to die yet. The seals know that. Only Mer who are ready to die will cross the borderline. Their families will come this far with them, but no farther.”

“It’s beautiful,” says Conor under his breath. “But they’re not all old, are they?”

I look where he’s pointing. He’s right. Among the old there are a few young Mer. One looks like a girl, younger than me.

“We get sick, just as you do. We have accidents, just as you do,” says Faro. “Not everyone lives to be old.”

“What’s that music?” asks Conor suddenly.

I strain my ears. I haven’t noticed any music.

“There it is again,” says Conor. “Listen!” He looks at me, his face bright with pleasure, but I still can’t hear anything. Faro looks at Conor with surprise, and something else which I can’t identify.

“What kind of music can you hear?” he asks.

“I don’t know,” says Conor. “It’s a bit like the sound you get when you hold a shell up to your ear. But it’s much sweeter, and it’s full of patterns. Listen, there it is again. Can’t you hear it, Saph?”

“No,” says Faro. “Neither of us can. It’s rare to hear it, even for us. And you’re human. Some Mer have the gift of hearing it all their lives, but most of us only hear it when we come to die. It’s the song the seals sing to us when we come to Limina.”

“This place is Limina?” asks Conor.

“Yes.”

“Of course. You’re right, that’s what they’re singing,” says Conor, and for a strange moment it’s as if he knows more about this place than Faro. “That’s what they are singing about. Listen, Saph. Try to hear it. It’s so beautiful.”

“I can’t hear it,” I say.

“You will one day,” says Faro. “Limina is where we all come, and the seals watch over us until we die. No Air Person has ever seen this.”

“But—”

“Your ancestors came here too, when they were wise,” says Faro. “This is where they left their bones. Do you think I could bring you here, if you weren’t bound to it by your blood? You believe you belong only to Air, but I promise you, one day you’ll cross into Limina alongside me.”

I want to argue, but I don’t, and as I stare out over the plain my arguments drift away. How beautiful it is. Ingo has given them birth, Ingo will receive them back in death. There’s nothing to be afraid of here. But how strange it is that Conor can hear the music and I can’t, even though I can swim alone in Ingo and Conor nearly died without Faro’s help. I wonder why that is. It doesn’t seem fair that only Conor can hear the seals’ music.

It doesn’t seem fair because you want to come first in Ingo, Sapphire, says a small inconvenient voice inside me. You quite liked it that Conor couldn’t keep up with you here in Ingo, didn’t you? It made a nice change, didn’t it?

Yes, I have to admit it. That little voice inside me is telling the truth. I was jealous. But how pathetic it would be, to be jealous of Conor, and the look on his face now as he listens to the song of the seals.

I belong here too. I am bound to it by my Mer blood. That’s what Faro said. Conor and I are both part of Ingo.

The three of us float there in a dream, Conor holding my wrist, Faro holding Conor’s. The grey seals patrol with their watchful eyes, and the Mer who have passed into Limina rest on the shimmering sand. Time seems to have disappeared. There is only now, and now might last for ever.

For ever. Never changing. No one ever coming to disturb it except families bringing those who are ready to cross the border into Limina—

No!

I jolt out of my dream. It’s like being shocked out of my sleep in the sunwater when Roger’s boat passed over.

This is the place where Roger is going to dive. This is where he wants to explore for wrecks. Where the Mer are resting, preparing to die, that’s where he’ll dive. In a place that’s so important to the Mer that Faro says the seals would even kill him, to protect Limina. They’d kill Faro. What would they do to a human trespasser? A shudder of terror runs over my skin.