Полная версия

Полная версияThe History of Antiquity, Vol. 5 (of 6)

502

Diod. 17, 66, 71; 19, 48; Strabo, p. 731; Plut. "Alex." 72.

503

Strabo, p. 523.

504

Burnouf, "Commentaire sur le Yaçna," p. 251.

505

Arrian, "Ind." 38-40; Strabo, p. 727, 728, 738; Plin. "H. N." 6, 26; cf. Ptol. 6, 4, 1.

506

"Bacch." 14-16.

507

Arrian, "Ind." 40.

508

Spiegel, "Eran," 2, 260.

509

Herod. 9, 122, 1, 171; Nicol. Damasc. fragm. 66, ed. Müller; Xenophon, "Cyri instit." 6, 2, 22; 8, 8, 5-12; Plato, "Legg." p. 695; Strabo, p. 734.

510

Herod. 1, 125.

511

Strabo, p. 727.

512

Above, p. 270. Strabo, p. 728, 730; Ptol. 6, 4.

513

Arrian, "Ind." 40; Strabo, p. 727.

514

Aeschylus speaks of a Maraphis among the kings of the Persians, "Pers." 778.

515

Above, p. 282.

516

The place has the same name as the tribe; Pasargadae cannot in any case mean "Persian camp," as Anaximenes maintains in Stephanus. Oppert believes that he has discovered in the Pisiyauvada of the inscription of Behistun the original form of the name Pasargadae, which is the Greek form of the Persian word. Pisiyauvada (paisi gauvuda) means "valley of springs;" "Peuple des Medes," p. 110.

517

So Rawlinson and Spiegel. E. Schrader translates III. of the Babylonian version: "From old from the fathers we were kings." Abutav appears as a fact to leave no doubt about this sense. Oppert now translates duvitataranam (IV. of the Persian text) by twice, i. e. in two epochs we were kings: "Rec. of the Past," 7, 88; but his previous translation, "in two tribes" (i. e. in the older and younger line), we were kings, exactly corresponds to the facts.

518

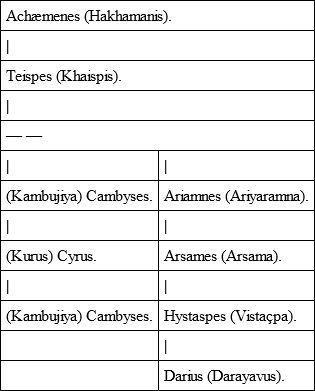

The list of the Achæmenids, which we obtain from a comparison of Herodotus (6, 11), and the inscription of Behistun 1, 3-8, is as follows:

519

If Darius calls himself the ninth Achæmenid, Xerxes also in Herodotus enumerates nine Achæmenids as his predecessors, in which enumeration, it is true, Cambyses occurs but once, while Teispes is twice mentioned, once as the ancestor of the older line, and then as the ancestor of the younger. On a broken cylinder which has just been brought from Babylon by Rassam, the genealogy of Cyrus is said to be given thus: Achæmenes, Teispes, Cyrus, Cambyses, Cyrus, – so the journals tell us. In this the older line has one member more as against the younger. Till the cylinder is published we must keep to the inscription of Behistun and Herodotus.

520

Aelian, "Hist. Anim." 12, 21.

521

Cyrus is said to have been forty years old in 558 B.C., so that he must have been born in 598 B.C., from which it follows that his father Cambyses was born in 620 at the latest. Astyages was married in 610, and must therefore have been born about 630 B.C.

522

"Persae," 956-960.

523

Joseph. "Antiq." 11, 2; Herod. 3, 77; Plat. "Legg." p. 695.

524

Herod. 3, 84.

525

This highest rank of nobility is called waspur in Pehlevi, and bar bithan is Aramaic. The book of Esther mentions the seven princes of the Persians and Medes, "who may behold the countenance of the king and have the first place in the kingdom," i. 14. The names of the six who aided Darius in slaying Gaumata, as given in Herodotus, agree with the inscription of Behistun, with the exception of one name. Herodotus gives Aspathines for the Ardumanis of Darius. The list of Ctesias is wholly different. If we examine them more closely we find that Ctesias has given the names of the sons of the comrades of Darius for the comrades themselves. Instead of Gobryas he puts Mardonius the son of Gobryas, instead of Otanes Anaphes (so we must read the name Onophes); Anaphes, according to Herod. 7, 62, is the son of Otanes. The name Hydarnes agrees with the inscription and with Herodotus, but the son of Hydarnes had the same name as his father (Herod. 7, 83, 211). The Barisses of Ctesias must be the eldest son of Intaphernes whom Darius allowed to live; he was called after his grandfather, Vayaçpara, as was often the case with the Persians. The Ariarathes, who afterwards governed Cappadocia, claimed to have sprung from Anaphes, whom Darius made satrap or king of Cappadocia. Anaphes was succeeded by a son of the same name; after him came Datames, Ariamnes, Ariarathes I., who governed Cappadocia at the time of Artaxerxes Ochus; his son Ariathes II. crucified Perdiccas in the year 322 B.C. when he had conquered him, though an old man of 82 years; Droysen, "Hellenismus," 22, 95. The Norondobates in Ctesias I cannot explain, unless we ought to read Rhodobates. Mithridates, who in Xenophon's time had been governor of Lycaonia from about 420 B.C., is called a son of Rhodobates (Diog. Laert. 3, 25), and his father and grandfather are said to have been viceroys of Pontus. The ancestor would be one of the seven, to whom the kingdom of Pontus was given for his services; Polyb. 5, 43. Mithridates Eupator calls himself the sixteenth after Darius; Appian, "Bell. Mith." c. 112; cf. Justin, 38, 7. These quotations will be sufficient to show that the rank of the six tribal princes of the Persians, like that of the chief princes, was originally hereditary, as the governorships left to their descendants outside Persia must have remained in their families.

526

p. 728, 729.

527

Strabo, p. 729, puts Pasargadae on the Cyrus. Stephanus (Πασσαργάδαι) following Anaximenes of Lampsacus, represents Pasargadae as first built by Cyrus; so Curt. 5, 11: Cyrus Pasargadum urbem condiderat. It cannot be doubted that Cyrus built there, and Alexander, according to Arrian (3, 18), found there the treasures of Cyrus. Strabo also tells us that Cyrus built the city and citadel, p. 730. From the accounts of the march of Alexander from Persepolis to Pasargadae, and from his return from the Indus to Pasargadae and Persepolis, it is clear that Pasargadae lay to the east or south-east of Persepolis. If Pasargadae is placed at Murghab, the only reason is the statement that the grave of Cyrus was at Pasargadae, and this grave has been identified with the pyramid of Murghab, in the immediate proximity of which a relief exhibits the picture of Cyrus. But the portrait of Cyrus there is very different from the portrait of Darius and his successors on the tombs at Rachmed, and Naksh-i-Rustem; and the building at Murghab may have served another purpose. According to Pliny ("H. N." 6, 26, 29) we ought to look for Pasargadae to the south of Lake Bakhtegan, near Fasa, or Darabgerd; flumen Sitioganus, quo Pasargadas septimo die navigatur. Sitioganus is the modern Sitaragan. Ptolemy puts Pasargadae in the neighbourhood of Caramania, and Oppert therefore identifies it with the ruins of Tell-i-Zohak near Fasa, and looks for the mountain Paraga of the inscriptions in the modern Forg: "Journal Asiat." 1872, p. 549.

528

Herod. 1, 98, 99.

529

Herod. 1, 112, πιστοτάτους τῶν δορυφόρων, while in the recapitulation, 1, 117, we have πιστοτάτους τῶν εὐνούχων.

530

Ctesias, "Fragm. Pers." 2, 5.

531

Nicol. Damasc. fragm. 66; Ctes. "Fragm. Pers." 2, 5; Tzetz. "Chil." 1, 1, 82 ff.

532

Athen. p. 633; Cic. "de Divin." 1, 23.

533

Justin, 1, 4-7; cf. 44, 4.

534

Polyæn. "Strat." 7, 6; 7, 45. But he also explains the change of fortune at Pasargadae in another way. When Cyrus fled to that place after his retreat, and many Persians deserted to the Medes, he spread abroad a report that on the following day 100,000 enemies of the Medes (Cadusians?) would come to his assistance; every man was to prepare a bundle of faggots for the allies. The deserter told this to the Medes, and when Cyrus in the night caused all the bundles to be lighted, the Medes, thinking that the Persians had received substantial assistance, deserted.

535

Strabo, p. 727, 730. Steph. Byzant. Πασσαργάδαι.

536

"De mulier. virtute," 5.

537

Diod. "Ex. de virt. et vit." p. 552, 553 (= 9, 24); cf. 4, 30.

538

Moses Choren. 1, 24-30, and appendix to the first book, according to Le Vaillant's translation.

539

The form and explanation of the legend of Asdahag in Moses, as well as the mention of Rustem Sakjig, who has the strength of ten elephants (2, 8), i. e. of Rustem of Sejestan, prove that the East-Iranian legend, as we find it in Firdusi, must have been current in Western Iran in the fourth century at the latest, if it came into Armenia in the fifth century. I do not think it probable that Moses took the legend of Tigran from Xenophon's narrative. The vision in a dream and the duel point to Armenian tradition.

540

1, 95.

541

"Cyri Instit." 1, 2, 1.

542

J. Mohl, "Livre des rois," Introd. p. 29.

543

It has been objected to this analysis that the marriage with the heiress may not have conveyed the throne ipso facto to the husband; it may have been open to the chieftains to elect a king out of the members of the royal family. This may be correct for the election of the Afghan chiefs at the present day by the heads of the families. How the succession to the throne was arranged among the Medes we do not know in any detail, or whether their chiefs had any importance at all; but we do see that the crown went from father to son from Deioces downwards. In any case, even under that hypothesis, the husband of the heiress had a nearer claim.

544

Herod. 3, 2. So Deinon and Lyceas of Naucratis in Athenaeus, p. 560.

545

Herod. 1, 207; 3, 75; 7, 11.

546

Cicero, "de Divin." 1, 23.

547

St. Martin on Lebeau, "Bas Empire," 2, 221.

548

"Cyri instit." 7, 3, 24.

549

Above, p. 299 ff.

550

Above, p. 34, 35, 36, 256.

551

Above, p. 110. Cf. Windischmann, "Zoroastrische Studien," s. 277.

552

Nöldeke, "Tabari," p. 12; Karnamak, s. 68.

553

"Politic." 5, 10, 24.

554

If Astyages was married to the daughter of Alyattes in the year 610 B.C. he must have been 18 or 20 years old at that time; between 610 and 558 the year of his fall there are 52 years. Moreover, according to Ctesias, Astyages outlived his fall at least ten years ("Fragm. Pers." 5). If this were the case, and Astyages did not die till 548, he cannot well have been born before 630 B.C. In Herodotus and Pompeius Trogus it is expressly said that Astyages had no son, and this is the motive which induces Harpagus not to put Cyrus to death, as he would in that case expose himself to the vengeance of the mother, the heiress to the throne. In Nicolaus also the daughter comes distinctly forward, and in Ctesias she is also the heiress (e. g. "Pers." 2); in the history of the overthrow and the death of Astyages, we hear of her constantly. At the death of Cyrus, her sons by the first marriage receive satrapies. In Ctesias, it is true, a brother of Amytis is incidentally mentioned, on the occasion of a later war of Cyrus ("Pers." 3). But as Ctesias is here following a Median version, and after the death of Astyages the husband of Amytis and not her supposed brother is removed out of the way, no importance can be attached to this.

555

Above, p. 369.

556

Above, p. 357. Nicol. Dam. Fragm. 66; Plut "Alex." c. 69; Plut. "De Mul. virt." 5.

557

According to the canon of Ptolemy, Cyrus dies 529 B.C. We arrive at the same year if we reckon back from the death of Darius. This took place five years after the battle of Marathon (Herod. 7, 1-4), i. e. 485 B.C. Darius reigned 36 years according to Herodotus and the canon of Ptolemy. An Egyptian pillar gives the year 34, a demotic contract the year 35 of his reign: he ascended the throne therefore in 521 B.C. Before him the Magian reigned for seven months, Cambyses for seven years and five months (Herod. 3, 66, 67). The canon of Ptolemy omits the Magian and gives Cambyses eight years, because it reckons by complete years; hence Cambyses ascended the throne in 529. As Cyrus, according to Herodotus, reigned 29 years after his accession (1, 214), the beginning of his reign over Media must be placed in 558. If Ctesias gives Cyrus a reign of 30 years ("Pers." 8), like Deinon (p. 369), and Justin (1, 8), and Eusebius a reign of 31 years, these statements may be reconciled by the fact that Cyrus may have taken up arms against Media 30 or 31 years before his death, and reigned 29 years after the overthrow of Astyages. Diodorus puts the beginning of Cyrus: Olymp. 55, 1 = 560 B.C. Africanus in Euseb. "Præp. Evang." 10, p. 488.

558

Ctes. "Pers. Ecl." 5; Tzetz. "Chil." 1, 1, 83; Justin, 1, 6. Yet Diodorus mentions the Barcanians together with the Hyrcanians (2, 2); Curtius (3, 2) represents the Barcanians as providing 12,000 men for the last Darius; Stephanus of Byzantium (Βαρκάνιοι) puts them beside the Hyrcanians. Yet all these statements may rest on the same misconception.

559

Herod. 1, 73; above, p. 378, note.

560

Herod. 2, 1; 3, 2; 7, 11.

561

Ctesias, "Pers." 8. The narrative of the death of Astyages follows the narrative of the wars against the Bactrians and Sacæ, and against Crœsus, and precedes the wars against the Derbiccians.

562

Herod. 9, 122.

563

Herod. 1, 177.

564

"Cyri instit." 5, 3, 22.

565

Strabo, p. 512.

566

Ptolem. 6, 2; Ammian, 23, 6. The rebellion of the Cadusians at a later time was mentioned by Xenoph. "Hellen." 2, 1, 13; Plut. "Artaxerx." 24; Diod. 15, 8; Justin, 10, 3. They fought with the last Darius at Arbela; Arrian, "Anab." 3, 11.

567

Crœsus, when he has crossed the Halys, is at once in Persian territory; Herod. 1, 72, 73.

568

Xenoph. "Cyri instit." 3, 1; 3, 2, 1, 2; 7, 2, 5; Diod. 31, 19.

569

The serious difficulty of Cyrus is shown by his rapid march back from Sardis with much the larger part of his army before the Greek cities, the Lycians and Carians were reduced. Cp. Vol. VI. chapters 8 and 9.

570

"Persic." 9.

571

Strabo, p. 730; Curt. 5, 6, 10; Arrian, "Anab." 3, 16, 18. The observation in Xenophon ("Cyri instit." 5, 2, 1), that Cyrus whenever he trod the soil of Persia gave a piece of gold to each Persian man and woman, may have arisen from the presents to the women of Pasargadæ.

572

"Cyri instit." 1, 2, 1.

573

"Cyri instit." 8, 5, 21 ff.

574

Plato, "Epp." 4, p. 320. Cf. "Menexen." p. 239.

575

"Legg." p. 693, 694. Cicero, ("de Republ." 1, 27, 28), calls Cyrus the most just, wise, and amiable of rulers.