Полная версия:

Scales of Justice

Ngaio Marsh

Scales of Justice

DEDICATION

For Stella

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Map

Cast of Characters

1. Swevenings

2. Nunspardon

3. The Valley of the Chyne

4. Bottom Meadow

5. Hammer Farm

6. The Willow Grove

7. Watt’s Hill

8. Jacob’s Cottage

9. Chyning and Uplands

10. Return to Swevenings

11. Between Hammer and Nunspardon

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Also by the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

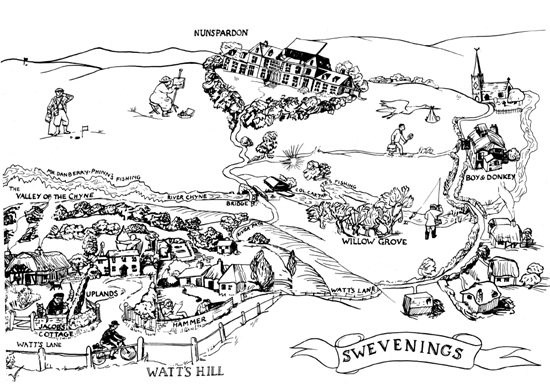

MAP

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Nurse Kettle Mr Octavius Danberry-Phinn Of Jacob’s Cottage Commander Syce Colonel Cartarette Of Hammer Farm Rose Cartarette His daughter Kitty Cartarette His wife Sir Harold Lacklander Bt. Of Nunspardon Lady Lacklander His wife George Lacklander Their son Dr Mark Lacklander George’s son Chief Detective-Inspector Alleyn

CHAPTER 1

Swevenings

Nurse Kettle pushed her bicycle to the top of Watt’s Hill and there paused. Sweating lightly, she looked down on the village of Swevenings. Smoke rose in cosy plumes from one or two chimneys; roofs cuddled into surrounding greenery. The Chyne, a trout stream, meandered through meadow and coppice and slid blamelessly under two bridges. It was a circumspect landscape. Not a faux-pas, architectural or horticultural, marred the seemliness of the prospect.

‘Really,’ Nurse Kettle thought with satisfaction, ‘it is as pretty as a picture.’ And she remembered all the pretty pictures Lady Lacklander had made in irresolute watercolour, some from this very spot. She was reminded, too, of those illustrated maps that one finds in the Underground, with houses, trees and occupational figures amusingly dotted about them. Seen from above, like this, Swevenings resembled such a map. Nurse Kettle looked down at the orderly pattern of field, hedge, stream, and land, and fancifully imposed upon it the curling labels and carefully naïve figures that are proper to picture-maps.

From Watt’s Hill, Watt’s Lane ran steeply and obliquely into the valley. Between the lane and the Chyne was contained a hillside divided into three strips, each garnished with trees, gardens and a house of considerable age. These properties belonged to three of the principal householders of Swevenings: Mr Danberry-Phinn, Commander Syce and Colonel Cartarette.

Nurse Kettle’s map, she reflected, would have a little picture of Mr Danberry-Phinn at Jacob’s Cottage surrounded by his cats, and one of Commander Syce at Uplands, shooting off his bow-and-arrow. Next door at Hammer Farm (only it wasn’t a farm now but had been much converted) it would show Mrs Cartarette in a garden chair with a cocktail shaker, and Rose Cartarette, her stepdaughter, gracefully weeding. Her attention sharpened. There, in point of fact, deep down in the actual landscape, was Colonel Cartarette himself, a lilliputian figure, moving along his rented stretch of the Chyne, east of Bottom Bridge, and followed at a respectful distance by his spaniel Skip. His creel was slung over his shoulder and his rod was in his hand.

‘The evening rise,’ Nurse Kettle reflected, ‘he’s after the Old ’Un.’ And she added to her imaginary map the picture of an enormous trout lurking near Bottom Bridge with a curly label above it bearing a legend: ‘The Old ’Un.’

On the far side of the valley on the private golf course at Nunspardon Manor there would be Mr George Lacklander, doing a solitary round with a glance (thought the gossip-loving Nurse Kettle) across the valley at Mrs Cartarette. Lacklander’s son, Dr Mark, would be shown with his black bag in his hand and a stork, perhaps, quaintly flying overhead. And to complete, as it were, the gentry, there would be old Lady Lacklander big-bottomed on a sketching stool and her husband, Sir Harold, on a bed of sickness, alas, in his great room, the roof of which, after the manner of pictorial maps, had been removed to display him.

In the map it would be demonstrated how Watt’s Lane, wandering to the right and bending back again, neatly divided the gentry from what Nurse Kettle called the ‘ordinary folk.’ To the west lay the Danberry-Phinn, the Syce, the Cartarette and above all the Lacklander demesnes. Neatly disposed along the east margin of Watt’s Lane were five conscientiously preserved thatched cottages, the village shop and, across Monk’s Bridge, the church and rectory and the Boy and Donkey.

And that was all. No Pulls-In for Carmen, no Olde Bunne Shoppes (which Nurse Kettle had learned to despise), no spurious half-timbering, marred the perfection of Swevenings. Nurse Kettle, bringing her panting friends up to the top of Watt’s Hill, would point with her little finger at the valley and observe triumphantly: ‘Where every prospect pleases,’ without completing the quotation, because in Swevenings not even Man was Vile.

With a look of pleasure on her shining and kindly face she mounted her bicycle and began to coast down Watt’s Lane. Hedges and trees flew by. The road surface improved and on her left appeared the quickset hedge of Jacob’s Cottage. From the far side came the voice of Mr Octavius Danberry-Phinn.

‘Adorable!’ Mr Danberry-Phinn was saying. ‘Queen of Delight! Fish!’ He was answered by the trill of feline voices.

Nurse Kettle turned to the footpath, dexterously backpedalled, wobbled uncouthly and brought herself to anchor at Mr Danberry-Phinn’s gate.

‘Good evening,’ she said, clinging to the gate and retaining her seat. She looked through the entrance cut in the deep hedge. There was Mr Danberry-Phinn in his Elizabethan garden giving supper to his cats. In Swevenings, Mr Phinn (he allowed his nearer acquaintances to neglect the hyphen) was generally considered to be more than a little eccentric, but Nurse Kettle was used to him and didn’t find him at all disconcerting. He wore a smoking-cap, tasselled, embroidered with beads; and falling to pieces. On top of this was perched a pair of ready-made reading-glasses which he now removed and gaily waved at her.

‘You appear,’ he said, ‘like some exotic deity mounted on an engine quaintly devised by Inigo Jones. Good evening to you, Nurse Kettle. Pray, what has become of your automobile?’

‘She’s having a spot of beauty treatment and a minor op’.’ Mr Phinn flinched at this relentless breeziness, but Nurse Kettle, unaware of his reaction, carried heartily on, ‘And how’s the world treating you? Feeding your kitties, I see.’

‘The Persons of the House,’ Mr Phinn acquiesced, ‘now, as you observe, sup. Fatima,’ he cried squatting on his plump haunches, ‘Femme fatale. Miss Paddy-Paws! A morsel more of haddock? Eat up, my heavenly felines.’ Eight cats of varying kinds responded but slightly to these overtures, being occupied with eight dishes of haddock. The ninth, a mother cat, had completed her meal and was at her toilet. She blinked once at Mr Phinn and with a tender and gentle expression stretched herself out for the accommodation of her three fat kittens.

‘The celestial milk-bar is now open,’ Mr Phinn pointed out with a wave of his hand.

Nurse Kettle chuckled obligingly. ‘No nonsense about her, at least,’ she said. ‘Pity some human mums I could name haven’t got the same idea,’ she added, with an air of professional candour. ‘Clever Pussy!’

‘The name,’ Mr Phinn corrected tartly, ‘is Thomasina Twitchett, Thomasina modulating from Thomas and arising out of the usual mistake and Twitchett …’ He bared his crazy-looking head. ‘Hommage à la Divine Potter. The boy children are Ptolemy and Alexis. The girl-child who suffers from a marked mother-fixation is Edie.’

‘Edie?’ Nurse Kettle repeated doubtfully.

‘Edie Puss, of course,’ Mr Phinn rejoined and looked fixedly at her.

Nurse Kettle, who knew that one must cry out against puns, ejaculated: ‘How you dare! Honestly!’

Mr Phinn gave a short cackle of laughter and changed the subject.

‘What errand of therapeutic mercy,’ he asked, ‘has set you darkling in the saddle? What pain and anguish wring which brow?’

‘Well, I’ve one or two calls,’ said Nurse Kettle, ‘but the long and the short of me is that I’m on my way to spend the night at the big house. Relieving with the old gentleman, you know.’

She looked across the valley to Nunspardon Manor.

‘Ah, yes,’ said Mr Phinn softly. ‘Dear me! May one inquire …? Is Sir Harold –?’

‘He’s seventy-five,’ said Nurse Kettle briskly, ‘and he’s very tired. Still, you never know with cardiacs. He may perk up again.’

‘Indeed?’

‘Oh, yes. We’ve got a day-nurse for him but there’s no nightnurse to be had anywhere so I’m stop-gapping. To help Dr Mark out, really.’

‘Dr Mark Lacklander is attending his grandfather?’

‘Yes. He had a second opinion but more for his own satisfaction than anything else. But there! Talking out of school! I’m ashamed of you, Kettle.’

‘I’m very discreet,’ said Mr Phinn.

‘So’m I, really. Well, I suppose I had better go on me way rejoicing.’

Nurse Kettle did a tentative back-pedal and started to wriggle her foot out of one of the interstices in Mr Phinn’s garden gate. He disengaged a sated kitten from its mother and rubbed it against his illshaven cheek.

‘Is he conscious?’ he asked.

‘Off and on. Bit confused. There now! Gossiping again! Talking of gossip,’ said Nurse Kettle, with a twinkle, ‘I see the Colonel’s out for the evening rise.’

An extraordinary change at once took place in Mr Phinn. His face became suffused with purple, his eyes glittered and he bared his teeth in a canine grin.

‘A hideous curse upon his sport,’ he said. ‘Where is he?’

‘Just below the bridge.’

‘Let him venture a handspan above it and I’ll report him to the authorities. What fly has he mounted? Has he caught anything?’

‘I couldn’t see,’ said Nurse Kettle, already regretting her part in the conversation, ‘from the top of Watt’s Hill.’

Mr Phinn replaced the kitten.

‘It is a dreadful thing to say about a fellow-creature,’ he said, ‘a shocking thing. But I do say advisedly and deliberately that I suspect Colonel Cartarette of having recourse to improper practices.’

It was Nurse Kettle’s turn to blush.

‘I am sure I don’t know to what you refer,’ she said.

‘Bread! Worms!’ said Mr Phinn, spreading his arms. ‘Anything! Tickling, even! I’d put it as low as that.’

‘I’m sure you’re mistaken.’

‘It is not my habit, Miss Kettle, to mistake the wanton extravagances of infatuated humankind. Look, if you will, at Cartarette’s associates. Look, if your stomach is strong enough to sustain the experience, at Commander Syce.’

‘Good gracious me, what has the poor Commander done!’

‘That man,’ Mr Phinn said, turning pale and pointing with one hand to the mother-cat and with the other in the direction of the valley; ‘that intemperate filibuster, who divides his leisure between alcohol and the idiotic pursuit of archery, that wardroom cupid, my God, murdered the mother of Thomasina Twitchett.’

‘Not deliberately, I’m sure.’

‘How can you be sure?’

Mr Phinn leant over his garden gate and grasped the handlebars of Nurse Kettle’s bicycle. The tassel of his smoking-cap fell over his face and he blew it impatiently aside. His voice began to trace the pattern of a much-repeated, highly relished narrative.

‘In the cool of the evening Madame Thorns, for such was her name, was wont to promenade in the bottom meadow. Being great with kit she presented a considerable target. Syce, flushed no doubt with wine, and flattering himself he cut the devil of a figure, is to be pictured upon his archery lawn. The instrument of destruction, a bow with the drawing power, I am told, of sixty pounds, is in his grip and the lust of blood in his heart. He shot an arrow in the air,’ Mr Phinn concluded, ‘and if you tell me that it fell to earth he knew not where I shall flatly refuse to believe you. His target, his deliberate mark, I am persuaded, was my exquisite cat. Thomasina, my fur of furs, I am speaking of your mamma.’

The mother-cat blinked at Mr Phinn and so did Nurse Kettle.

‘I must say,’ she thought, ‘he really is a little off.’ And since she had a kind heart she was filled with a vague pity for him.

‘Living alone,’ she thought, ‘with only those cats. It’s not to be wondered at, really.’

She gave him her brightest professional smile and one of her standard valedictions.

‘Ah, well,’ said Nurse Kettle, letting go her anchorage on the gate, ‘be good, and if you can’t be good be careful.’

‘Care,’ Mr Danberry-Phinn countered with a look of real intemperance in his eye, ‘killed the Cat. I am not likely to forget it. Good evening to you, Nurse Kettle.’

II

Mr Phinn was a widower but Commander Syce was a bachelor. He lived next to Mr Phinn, in a Georgian house called Uplands, small and yet too big for Commander Syce, who had inherited it from an uncle. He was looked after by an ex-naval rating and his wife. The greater part of the grounds had been allowed to run to seed, but the kitchen garden was kept up by the married couple and the archery lawn by Commander Syce himself. It overlooked the valley of the Chyne and was, apparently, his only interest. At one end in fine weather stood a target on an easel and at the other on summer evenings from as far away as Nunspardon, Commander Syce could be observed, in the classic pose, shooting a round from his sixty-pound bow. He was reputed to be a fine marksman and it was noticed that however much his gait might waver, his stance, once he had opened his chest and stretched his bow, was that of a rock. He lived a solitary and aimless life. People would have inclined to be sorry for him if he had made any sign that he would welcome their sympathy. He did not do so and indeed at the smallest attempt at friendliness would sheer off, go about and make away as fast as possible. Although never seen in the bar, Commander Syce was a heroic supporter of the pub. Indeed, as Nurse Kettle pedalled up his overgrown drive, she encountered the lad from the Boy and Donkey pedalling down it with his bottle-carrier empty before him.

‘There’s the Boy,’ thought Nurse Kettle, rather pleased with herself for putting it that way, ‘and I’m very much afraid he’s just paid a visit to the Donkey.’

She, herself, had a bottle for Commander Syce, but it came from the chemist at Chyning. As she approached the house she heard the sound of steps on the gravel and saw him limping away round the far end, his bow in his hand and his quiver girt about his waist. Nurse Kettle pedalled after him.

‘Hi!’ she called out brightly. ‘Good evening, Commander!’

Her bicycle wobbled and she dismounted.

Syce turned, hesitated for a moment and then came towards her.

He was a fairish, sunburned man who had run to seed. He still reeked of the Navy and, as Nurse Kettle noticed when he drew nearer, of whisky. His eyes, blue and bewildered, stared into hers.

‘Sorry,’ he said rapidly. ‘Good evening. I beg your pardon.’

‘Dr Mark,’ she said, ‘asked me to drop in while I was passing and leave your prescription for you. There we are. The mixture as before.’

He took it from her with a darting movement of his hand. ‘Most awfully kind,’ he said. ‘Frightfully sorry. Nothing urgent.’

‘No bother at all,’ Nurse Kettle rejoined, noticing the tremor of his hand. ‘I see you’re going to have a shoot.’

‘Oh, yes. Yes,’ he said loudly, and backed away from her. ‘Well, thank you, thank you, thank you.’

‘I’m calling in at Hammer. Perhaps you won’t mind my trespassing. There’s a footpath down to the right-of-way, isn’t there?’

‘Of course. Please do. Allow me.’

He thrust his medicine into a pocket of his coat, took hold of her bicycle and laid his bow along the saddle and handlebars.

‘Now I’m being a nuisance,’ said Nurse Kettle cheerfully. ‘Shall I carry your bow?’

He shied away from her and began to wheel the bicycle round the end of the house. She followed him, carrying the bow and talking in the comfortable voice she used for nervous patients. They came out on the archery lawn and upon a surprising and lovely view over the little valley of the Chyne. The trout stream shone like pewter in the evening light, meadows lay as rich as velvet on either side, the trees looked like pincushions, and a sort of heraldic glow turned the whole landscape into the semblance of an illuminated illustration to some forgotten romance. There was Major Cartarette winding in his line below Bottom Bridge and there up the hill on the Nunspardon golf course were old Lady Lacklander and her elderly son George, taking a post-prandial stroll.

‘What a clear evening,’ Nurse Kettle exclaimed with pleasure. ‘And how close everything looks. Do tell me, Commander,’ she went on, noticing that he seemed to flinch at this form of address, ‘with this bow of yours could you shoot an arrow into Lady Lacklander?’

Syce darted a look at the almost square figure across the little valley. He muttered something about a clout at two hundred and forty yards and limped on. Nurse Kettle, chagrined by his manner, thought: ‘What you need, my dear, is a bit of gingering up.’

He pushed her bicycle down an untidy path through an overgrown shrubbery and she stumped after him.

‘I have been told,’ she said, ‘that once upon a time you hit a mark you didn’t bargain for, down there.’

Syce stopped dead. She saw that beads of sweat had formed on the back of his neck. ‘Alcoholic,’ she thought. ‘Flabby. Shame. He must have been a fine man when he looked after himself.’

‘Great grief!’ Syce cried out, thumping his fist on the seat of her bicycle, ‘you mean the bloody cat!’

‘Well!’

‘Great grief, it was an accident. I’ve told the old perisher! An accident! I like cats.’

He swung round and faced her. His eyes were misted and his lips trembled. ‘I like cats,’ he repeated.

‘We all make mistakes,’ said Nurse Kettle, comfortably.

He held his hand out for the bow and pointed to a little gate at the end of the path.

‘There’s the gate into Hammer,’ he said, and added with exquisite awkwardness, ‘I beg your pardon, I’m very poor company as you see. Thank you for bringing the stuff. Thank you, thank you.’

She gave him the bow and took charge of her bicycle. ‘Dr Mark Lacklander may be very young,’ she said bluffly, ‘but he’s as capable a GP as I’ve come across in thirty years’ nursing. If I were you, Commander, I’d have a good down-to-earth chinwag with him. Much obliged for the assistance. Good evening to you.’

She pushed her bicycle through the gate into the well-tended coppice belonging to Hammer Farm and along a path that ran between herbaceous borders. As she made her way towards the house she heard behind her at Uplands, the twang of a bow string and the ‘tock’ of an arrow in a target.

‘Poor chap,’ Nurse Kettle muttered, partly in a huff and partly compassionate. ‘Poor chap! Nothing to keep him out of mischief.’ And with a sense of vague uneasiness, she wheeled her bicycle in the direction of the Cartarettes’ rose garden where she could hear the snip of garden secateurs and a woman’s voice quietly singing.

‘That’ll be either Mrs,’ thought Nurse Kettle, ‘or the stepdaughter. Pretty tune.’

A man’s voice joined in, making a second part.

‘Come away, come away Death

And in sad cypress let me be laid.’

The words, thought Nurse Kettle, were a trifle morbid but the general effect was nice. The rose garden was enclosed behind quickset hedges and hidden from her, but the path she had taken led into it, and she must continue if she was to reach the house. Her rubber-shod feet made little sound on the flagstones and the bicycle discreetly clicked along beside her. She had an odd feeling that she was about to break in on a scene of exquisite intimacy. She approached a green archway and as she did so the woman’s voice broke off from its song, and said: ‘That’s my favourite of all.’

‘Strange,’ said a man’s voice that fetched Nurse Kettle up with a jolt, ‘strange, isn’t it, in a comedy, to make the love songs so sad! Don’t you think so, Rose? Rose … Darling …’

Nurse Kettle tinkled her bicycle bell, passed through the green archway and looked to her right. She discovered Miss Rose Cartarette and Dr Mark Lacklander gazing into each other’s eyes with unmistakable significance.