Полная версия:

Light Thickens

The Ngaio March Collection

For James Laurenson who played The Thane and for Helen Thomas (Holmes) who was his Lady, in the third production of the play by The Canterbury University Players.

Table of Contents

Cover Page

Title Page

Dedication

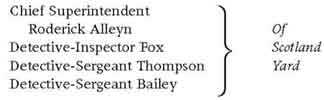

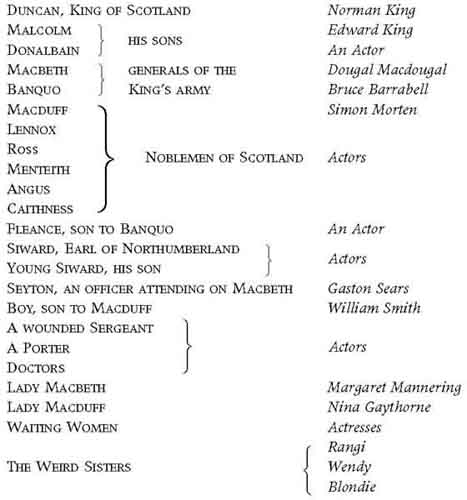

Cast of Characters

Part One: Curtain Up

CHAPTER 1 First Week

CHAPTER 2 Second Week

CHAPTER 3 Third Week

CHAPTER 4 Fourth Week

CHAPTER 5 Fifth Week. Dress Rehearsals and First Night

Part Two: Curtain Call

CHAPTER 6 Catastrophe

CHAPTER 7 The Junior Element

CHAPTER 8 Development

CHAPTER 9 Finis

By the Same Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Cast of Characters

Peregrine Jay Director, Dolphin Theatre Emily Jay His wife Crispin Jay Their eldest son Robin Jay Their second son Richard Jay Their youngest son Annie Their cook Doreen Her daughter Jeremy Jones Designer, Dolphin Theatre Winter Morris Business Manager Mrs Abrams Secretary Bob Masters Stage Director Charlie Assistant Stage Manager Ernie Property Master Nanny Miss Mannering’s dresser Mrs Smith Mother of William Marcello A restaurateur The Stage-Door Keeper

Sir James Curtis Pathologist

DOLPHIN THEATRE

MACBETH

by

William Shakespeare

Sundry soldiers, servants and apparitions

The Scene: Scotland and England

The play directed by PEREGRINE JAY

Setting and Costumes by JEREMY JONES

CHAPTER 1 First Week

Peregrine Jay heard the stage door at the Dolphin open and shut and the sound of voices. His scenic and costume designer and lights manager came through to the open stage. They wheeled out three specially built racks, unrolled their drawings for the production of Macbeth and pinned them up.

They were stunning. A permanent central rough stone stairway curving up to Duncan’s chamber. Two turntables articulating with this to represent, on the right, the outer façade of Inverness Castle or the inner courtyard with, on the left, a high stone platform with a gallows and a dangling rag-covered skeleton, or, turned, another wall of the courtyard. The central wall was a dull red arras behind the stairway and open sky.

The lighting director showed a dozen big drawings of the various sets with the startling changes brought about by his craft. One of these was quite lovely: an opulent evening in front of the castle with the setting sun bathing everything in splendour. One felt the air to be calm, gentle and full of the sound of wings. And then, next to it, the same scene with the enormous doors opened, a dark interior, torches, a piper and the Lady in scarlet coming to welcome the fated visitor.

Jeremy,’ Peregrine said, ‘you’ve done us proud.’

‘OK?’

‘It’s so right! It’s so bloody right. Here! Let’s up with the curtain. Jeremy?’

The designer went offstage and pressed a button. With a long-drawn-out sigh the curtain rose. The shrouded house waited.

‘Light them, Jeremy! Blackout and lights on them. Can you?’

‘It won’t be perfect but I’ll try.’

‘Just for the hell of it, Jeremy.’

Jeremy laughed, moved the racks and went to the lights console.

Peregrine and the others filed through a pass-door to the front-of-house. Presently there was a total blackout and then, after a pause, the drawings were suddenly there, alive in the midst of nothing and looking splendid.

‘Only approximate, of course,’ Jeremy said in the dark.

‘Let’s keep this for the cast to see. They’re due now.’

‘You don’t want to start them off with broken legs, do you?’ asked somebody’s voice in the dark.

There was an awkward pause.

‘Well – no. Put on the light in the passage,’ said Peregrine in a voice that was a shade too off-hand. ‘No,’ he shouted. ‘Bring down the curtain again, Jeremy. We’ll do it properly.’

The stage door was opened and more voices were heard, two women’s and a man’s. They came in exclaiming at the dark.

‘All right, all right,’ Peregrine called out cheerfully. ‘Stay where you are. Lights, Jeremy, would you? Just while people are coming in. Thank you. Come down in front, everybody. Watch how you go. Splendid.’

They came down. Margaret Mannering first, complaining about the stairs in her wonderful warm voice with little breaks of laughter, saying she knew she was unfashionably punctual. Peregrine hurried to meet her. ‘Maggie, darling! It’s all meant to start us off with a bang, but I do apologize. No more steps. Here we are. Sit down in the front row. Nina! Are you all right? Come and sit down, love. Bruce! Welcome, indeed. I’m so glad you managed to fit us in with television.’

I’m putting it on a bit thick, he thought. Nerves! Here they all come. Steady now.

They arrived singly and in pairs, having met at the door. They greeted Peregrine and one another extravagantly or facetiously and all of them asked why they were sitting in front and not on stage or in the rehearsal room. Peregrine kept count of heads. When they got to seventeen and then to nineteen he knew they were waiting for only one: the Thane.

He began again, counting them off. Simon Morten – Macduff. A magnificent figure, six foot two. Dark. Black eyes with a glitter. Thick black hair that sprang in short-clipped curls from his skull. A smooth physique not yet running to fat and a wonderful voice. Almost too good to be true. Bruce Barrabell – Banquo. Slight. Five foot ten inches tall. Fair to sandy hair. Beautiful voice. And the King? Almost automatic casting – he’d played every Shakespearean king in the canon except Lear and Claudius, and played them all well if a little less than perfectly. The great thing about him was, above all, his royalty. He was more royal than any of the remaining crowned heads of Europe and his name was actually King: Norman King. The Malcolm was, in real life, his son – a young man of nineteen – and the resemblance was striking.

There was Lennox, the sardonic man. Nina Gaythorne, the Lady Macduff, who was talking very earnestly with the Doctor. And I don’t mind betting it’s all superstition, thought Peregrine uneasily. He looked at his watch: twenty minutes late. I’ve half a mind to start without him, so I have.

A loud and lovely voice and the bang of the stage door.

Peregrine hurried through the pass door and up on the stage.

‘Dougal, my dear fellow, welcome,’ he shouted.

‘But I’m so sorry, dear boy. I’m afraid I’m a fraction late. Where is everybody?’

‘In front. I’m not having a reading.’

‘Not?’

‘No. A few words about the play. The working drawings and then away we go.’

‘Really?’

‘Come through. This way. Here we go.’

Peregrine led the way. ‘The Thane himself, everybody,’ he announced.

It gave Sir Dougal Macdougal an entrance. He stood for a moment on the steps into the front-of-house, an apologetic grin transforming his face. Such a nice chap, he seemed to be saying. No upstage nonsense about him. Everybody loves everybody. Yes. He saw Margaret Mannering. Delight! Acknowledgement! Outstretched arms and a quick advance. ‘Maggie! My dear! How too lovely!’ Kissing of hands and both cheeks. Everybody felt as if the central heating had been turned up another five points. Suddenly they all began talking.

Peregrine stood with his back to the curtain, facing the company with whom he was about to take a journey. Always it felt like this. They had come aboard: they were about to take on other identities. In doing this something would happen to them all: new ingredients would be tried, accepted or denied. Alongside them were the characters they must assume. They would come closer and, if the casting was accurate, slide together. For the time they were on stage they would be one. So he held. And when the voyage was over they would all be a little bit different.

He began talking to them.

‘I’m not starting with a reading,’ he said. ‘Readings are OK as far as they go for the major roles, but bit parts are bit parts and as far as the Gentlewoman and the Doctor are concerned, once they arrive they are bloody important, but their zeal won’t be set on fire by sitting around waiting for a couple of hours for their entrance.

‘Instead I’m going to invite you to take a hard look at this play and then get on with it. It’s short and it’s faulty. That is to say, it’s full of errors that crept into whatever script was handed to the printers. Shakespeare didn’t write the silly Hecate bits, so out she comes. It’s compact and drives quickly to its end. It’s remorseless. I’ve directed it in other theatres twice, each time I may say successfully and without any signs of bad luck, so I don’t believe in the bad luck stories associated with it and I hope none of you do either. Or if you do, you’ll keep your ideas to yourselves.’

He paused for long enough to sense a change of awareness in his audience and a quick, instantly repressed movement of Nina Gaythorne’s hands.

‘It’s straightforward,’ he said. ‘I don’t find any major difficulties or contradictions in Macbeth. He is a hypersensitive, morbidly imaginative man beset by an overwhelming ambition. From the moment he commits the murder he starts to disintegrate. Every poetic thought, magnificently expressed, turns sour. His wife knows him better than he knows himself and from the beginning realizes that she must bear the burden, reassure her husband, screw his courage to the sticking-point, jolly him along. In my opinion,’ Peregrine said, looking directly at Margaret Mannering, ‘she’s not an iron monster who can stand up to any amount of hard usage. On the contrary, she’s a sensitive creature who has an iron will and has made a deliberate evil choice. In the end she never breaks but she talks and walks in her sleep. Disastrously.’

Maggie leant forward, her hands clasped, her eyes brilliantly fixed on his face. She gave him a little series of nods. At the moment, at least, she believed him.

‘And she’s as sexy as hell,’ he added. ‘She uses it. Up to the hilt.’

He went on. The witches, he said, must be completely accepted. The play was written in James I’s time at his request. James I believed in witches. In their power and their malignancy. ‘Let us show you,’ said Peregrine, ‘what I mean. Jeremy, can you?’

Blackout, and there were the drawings, needle-sharp in their focused lights.

‘You see the first one,’ Peregrine said. ‘That’s what we’ll go up on, my dears. A gallows with its victim, picked clean by the witches. They’ll drop down from it and dance widdershins round it. Thunder and lightning. Caterwauls. The lot. Only a few seconds and then they’ll leap up and we’ll see them in mid-air. Blackout. They’ll fall behind the high rostrum on to a pile of mattresses. Gallows away. Pipers. Lighted torches and we’re off.’

Well, he thought, I’ve got them. For the moment. They’re caught. And that’s all one can hope for. He went through the rest of the cast, noting how economically the play was written and how completely the inherent difficulty of holding the interest in a character as seemingly weak as Macbeth was overcome.

‘Weak?’ asked Dougal Macdougal. ‘You think him weak, do you?’

‘Weak in respect of this one monstrous thing he feels himself drawn towards doing. He’s a most successful soldier. You may say “larger than life”. He “takes the stage”, cuts a superb figure. The King has promised he will continue to shower favours upon him. Everything is as rosy as can be. And yet – and yet –’

‘His wife?’ Dougal suggested. ‘And the witches!’

‘Yes. That’s why I say the witches are enormously important. One has the feeling that they are conjured up by Macbeth’s secret thoughts. There’s not a character in the play that questions their authority. There have been productions, you know, that bring them on at different points, silent but menacing, watching their work.

‘They pull Macbeth along the path to that one definitive action. And then, having killed the King, he’s left – a murderer. For ever. Unable to change. His morbid imagination takes charge. The only thing he can think of is to kill again. And again. Notice the imagery. The play closes in on him. And on us. Everything thickens. His clothes are too big, too heavy. He’s a man in a nightmare.

‘There’s the break, the breather for the leading actor that comes in all the tragedies. We see Macbeth once again with the witches and then comes the English scene with the boy Malcolm taking his oddly contorted way of finding out if Macduff is to be trusted, his subsequent advance into Scotland, the scene of Lady Macbeth speaking of horrors with the strange, dead voice of the sleepwalker.

‘And then we see him again; greatly changed; aged, desperate, unkempt; his cumbersome royal robes in disarray, attended still by Seyton who has grown in size. And so to the end.’

He waited for a moment. Nobody spoke.

‘I would like,’ said Peregrine, ‘before we block the opening scenes to say a brief word about the secondary parts. It’s the fashion to say they’re uninteresting. I don’t agree. About Lennox, in particular. He’s likeable, down to earth, quick-witted but slow to make the final break. There’s evidence in the imperfect script of some doubt about who says what. We will make Lennox the messenger to Lady Macduff. When next we see him he’s marching with Malcolm. His scene with an unnamed thane (we’ll give the lines to Ross) when their suspicion of Macbeth, their nosing out of each other’s attitudes, develops into a tacit understanding, is “modern” in treatment, almost black comedy in tone.’

‘And the Seyton?’ asked a voice from the rear. A very deep voice.

‘Ah, Seyton. There again, obviously, he’s “Sirrah”, the unnamed servant who accompanies Macbeth like a shadow, who carries his great claidheamh-mor, who joins the two murderers and later in the play emerges with a name – Seyton. He has hardly any lines but he’s ominous. A big, silent, ever-present, amoral fellow who only leaves his master at the very end. We’re casting Gaston Sears for the part. My Sears, as you all know, in addition to being an actor is an authority on medieval weapons and is already working for us in that capacity.’ There was an awkward silence followed by an acquiescent murmur.

The saturnine person, sitting alone, cleared his throat, folded his arms and spoke. ‘I shall carry,’ he announced, basso-profundo, ‘a claidheamh-mor.’

‘Quite so,’ Peregrine said. ‘You are the sword-bearer. As for the – ‘

‘ – which has been vulgarized into “claymore”. I prefer “claidheamh-mor” meaning “great sword”, it being – ‘

‘Quite so, Gaston. And now – ‘

For a time the voices mingled, the bass one coming through with disjointed phrases: ‘…Magnus’s leg-biter…quillons formed by turbulent protuberance…’

‘To continue,’ Peregrine shouted. The sword-bearer fell silent.

‘And the witches?’ asked a helpful witch.

‘Entirely evil,’ answered the relieved Peregrine. ‘Dressed like fantastic parodies of Meg Merrilies but with terrible faces. We don’t see their faces until “look not like the inhabitants of the earth and yet are on’t,” when they are suddenly revealed. They smell abominably.’

‘And speak?’

‘Braid Scots.’

‘What about me, Perry? Braid Scots too?’ suggested the porter.

‘Yes. You enter through the central trap, having been collecting fuel in the basement. And,’ Peregrine said with ill-concealed pride, ‘the fuel is bleached driftwood and most improperly shaped. You address each piece in turn as a farmer, as an equivocator and as an English tailor, and you consign them all to the fire.’

‘I’m a funny man?’

‘We hope so.’

‘Aye. A-weel, it’s a fine idea, I’ll give it that. Och, aye. A bonny notion,’ said the porter.

He chuckled and mouthed and Peregrine wished he wouldn’t, but he was a good Scots actor.

He waited for a moment, wondering how much he had gained of their confidence. Then he turned to the designs and explained how they would work and then to the costumes.

‘I’d like to say here and now that these drawings and those for the sets – Jeremy has done both – are, to my mind, exactly right. Notice the suggestion of the clan tartans: a sort of primitive pre-tartan. The cloak is a distinctive check affair. All Macbeth’s servitors and servitors of royal personages wore their badges and the livery of their masters. Lennox, Angus and Ross wear their own distinctive cloaks with the clan check. Banquo and Fleance have particularly brilliant ones, blood-red with black and silver borders. For the rest, thonged trousers, fur jerkins, and sheepswool chaps. Massive jewellery. Great jewelled bosses, heavy necklets and heavy bracelets, in Macbeth’s case reaching up to the elbow and above it. The general effect is heavy, primitive but incidentally extremely sexy. Gauntlets, fringed and ornamented. And the crowns! Macbeth’s in particular. Huge and heavy it must look.’

‘Look,’ said Macdougal, ‘being the operative word, I hope.’

‘Yes, of course. We’ll have it made of plastic. And Maggie…do you like what you see, darling?’

What she saw was a skin-tight gown of dull metallic material, slit up one side to allow her to walk. A crimson, heavily furred garment was worn over it, open down the front. She had only one jewel, a great clasp.

‘I hope I’ll fit it,’ said Maggie.

‘You’ll do that,’ he said, ‘and now – ‘ he was conscious of a tightness under his belt – ‘we’ll clear stage and get down to business. Oh! There’s one point I’ve missed. You will see that for our first week some of the rehearsals are at night. This is to accommodate Sir Dougal who is shooting the finals of his new film. The theatre is dark, the current production being on tour. It’s a bit out of the ordinary, I know, and I hope nobody finds it too awkward?’

There was a silence during which Sir Dougal with spread arms mimed a helpless apology.

‘I can’t forbear saying it’s very inconvenient,’ said Banquo.

‘Are you filming?’

‘Not precisely. But it might arise.’

‘We’ll hope it doesn’t,’ Peregrine said. ‘Right? Good. Clear stage, please, everybody. Scene 1. The witches.’

II

‘It’s going very smoothly,’ said Peregrine, three days later. ‘Almost too smoothly. Dougal’s uncannily lamblike and everyone told me he was a Frankenstein’s Monster to work with.’

‘Keep your fingers crossed,’ said his wife, Emily. ‘It’s early days yet.’

‘True.’ He looked curiously at her. ‘I’ve never asked you,’ he said.

‘Do you believe in it? The superstition business?’

‘No,’ she said quickly.

‘Not the least tiny bit? Really?’

Emily looked steadily at him. ‘Truly?’ she asked.

‘Yes.’

‘My mother was a one hundred per cent Highlander.’

‘So?’

‘So it’s not easy to give you a direct answer. Some superstitions – most, I think – are silly little matters of habit: a pinch of spilt salt over the left shoulder. One may do it without thinking but if one doesn’t it’s no great matter – that sort of thing. But – there are other ones. Not silly. I don’t believe in them, but I think I avoid them.’

‘Like the Macbeth ones?’

‘Yes. But I didn’t mind you doing it. Or not enough to try to stop you. Because I don’t really believe,’ said Emily very firmly.

‘I don’t believe at all. Not at any level. I’ve done two productions of the play and they both were accident-free and very successful. As for the instances they drag up – Macbeth’s sword breaking and a bit of it hitting someone in the audience or a dropped weight narrowly missing an actor’s head – if they’d happened in any other play nobody would have said it was an unlucky play. How about Rex Harrison’s hairpiece being caught in a chandelier and whisked up into the flies? Nobody said My Fair Lady was unlucky.’

‘Nobody dared to mention it, I should think.’

‘There is that, of course,’ Peregrine agreed.

‘All the same, it’s not a fair example.’

‘Why isn’t it?’

‘Well, it’s not serious. I mean, well…’

‘You wouldn’t say that if you’d been there, I dare say,’ said Peregrine.

He walked over to the window and looked at the Thames: at the punctual late-afternoon traffic. It congealed on the south bank, piled up, broke out into a viscous stream and crossed by bridge to the north bank. Above it, caught by the sun, shone the theatre: not very big but conspicuous in its whiteness and, because of the squat mess of little riverside buildings that surrounded it, appearing tall, even majestic.

‘You can tell which of them’s bothered about the bad luck stories,’ he said. ‘They won’t say his name. They talk about “the Thane” and “the Scots play” and “the Lady”. It’s catching. Lady Macduff – Nina Gaythorne, silly little ass – is steeped up to the eyebrows in it. And talks about it. Stops if she sees I’m about but she does all right, and they listen to her.’