Полная версия:

Hand in Glove

Through the side window, Nicola looked across Mr Period’s rose garden, to a quickset hedge and an iron gate leading into a lane. Beyond this gate was a trench with planks laid across it, a heap of earth and her old friend the truck, from which, with the aid of the crane, the workmen were unloading drain-pipes.

Distantly and overhead, she heard male voices. Her acquaintance of the train (what had the driver called him?) and his step-father, Nicola supposed.

She was thinking of him with amusement when the door opened and Mr Pyke Period came in.

III

He was a tall, elderly man with a marked stoop, silver hair, large brown eyes and a small mouth. He was beautifully dressed with exactly the correct suggestion of well-worn scrupulously tended tweed.

He advanced upon Nicola with curved arm held rather high and bent at the wrist. The Foreign Office, or at the very least, Commonwealth Relations, was invoked.

‘This is really kind of you,’ said Mr Pyke Period, ‘and awfully lucky for me.’

They shook hands.

‘Now, do tell me,’ Mr Period continued, ‘because I’m the most inquisitive old party and I’m dying to know – you are Basil’s daughter, aren’t you?’

Nicola, astounded, said that she was.

‘Basil Maitland-Mayne?’ he gently insisted.

‘Yes, but I don’t make much of a to-do about the “Maitland”,’ said Nicola.

‘Now, that’s naughty of you. A splendid old family. These things matter.’

‘It’s such a mouthful.’

‘Never mind! So you’re dear old Basil’s gel! I was sure of it. Such fun for me because, do you know, your grandfather was one of my very dear friends. A bit my senior, but he was one of those soldiers of the old school who never let you feel the gap in ages.’

Nicola, who remembered her grandfather as an arrogant, declamatory old egoist, managed to make a suitable rejoinder. Mr Period looked at her with his head on one side.

‘Now,’ he said gaily, ‘I’m going to confess. Shall we sit down? Do you know, when I called on those perfectly splendid people to ask about typewriting and they gave me some names from their books, I positively leapt at yours. And do you know why?’

Nicola had her suspicions and they made her feel uncomfortable. But there was something about Mr Period – what was it? – something vulnerable and foolish, that aroused her compassion. She knew she was meant to smile and shake her head and she did both.

Mr Period said, sitting youthfully on the arm of a leather chair: ‘It was because I felt that we would be working together on – dear me, too difficult! – on a common ground. Talking the same language.’ He waited for a moment and then said cosily: ‘And you now know all about me. I’m the most dreadful old anachronism – a Period Piece, in fact.’

As Nicola responded to this joke she couldn’t help wondering how often Mr Period had made it.

He laughed delightedly with her. ‘So, speaking as one snob to another,’ he ended, ‘I couldn’t be more enchanted that you are you. Well, never mind! One’s meant not to say such things in these egalitarian days.’

He had a conspiratorial way of biting his under-lip and lifting his shoulders: it was indescribably arch. ‘But we mustn’t be naughty,’ said Mr Pyke Period.

Nicola said: ‘They didn’t really explain at the agency exactly what my job is to be.’

‘Ah! Because they didn’t exactly know. I was coming to that.’

It took him some time to come to it, though, because he would dodge about among innumerable parentheses. Finally, however, it emerged that he was writing a book. He had been approached by the head of a publishing firm.

‘Wonderful,’ Nicola said, ‘actually to be asked by a publisher to write.’

He laughed. ‘My dear child, I promise you it would never have come from me. Indeed, I thought he must be pulling my leg. But not at all. So in the end I madly consented and – and there we are, you know.’

‘Your memoirs, perhaps?’ Nicola ventured.

‘No. No, although I must say – but no – You’ll never guess!’

She felt that she never would and waited.

‘It’s – how can I explain? Don’t laugh! It’s just that in these extraordinary times there are all sorts of people popping up in places where one would least expect to find them: clever, successful people, we must admit, but not, as we old fogies used to say – “not quite-quite”. And there they find themselves, in a milieu, where they really are, poor darlings, at a grievous loss.’

And there it was: Mr Pyke Period had been commissioned to write a book on etiquette. Nicola suspected that his publisher had displayed a remarkably shrewd judgement. The only book on etiquette she had ever read, a Victorian work unearthed in an attic by her brother, had been a favourite source for ribald quotation. ‘“It is a mark of ill-breeding in a lady,”’ Nicola’s brother would remind her, ‘“to look over her shoulder, still more behind her, when walking abroad.”’

‘“There should be no diminution of courteous observance,”’ she would counter, ‘“in the family circle. A brother will always rise when his sister enters the drawing-room and open the door to her when she shows her intention of quitting it.”’

‘“While on the sister’s part some slight acknowledgement of his action will be made: a smile or a quiet ‘thank you’ will indicate her awareness of the little attention.”’

Almost as if he had read her thoughts, Mr Period was saying: ‘Of course, one knows all about these delicious Victorian offerings – quite wonderful. And there have been contemporaries: poor Felicité Sankie-Bond, after their crash, don’t you know. And one mustn’t overlap with dear Nancy. Very diffy. In the meantime –’

In the meantime, it at last transpired, Nicola was to make a type-written draft of his notes and assemble them under their appropriate headings. These were: ‘The Ball-dance’, Trifles that Matter’, ‘The Small Dinner’, ‘The Partie Carrée’, ‘Addressing Our Letters & Betters’, ‘Awkwiddities’, ‘The Debutante – lunching and launching’, ‘Tips on Tipping’.

And bulkily, in a separate compartment, ‘The Compleat Letter-Writer’.

She was soon to learn that letter-writing was a great matter with Mr Pyke Period.

He was, in fact, famous for his letters of condolence.

IV

They settled to work: Nicola at her table near the front French windows, Mr Period at his desk in the side one.

Her job was an exacting one. Mr Period evidently jotted down his thoughts, piecemeal, as they had come to him and it was often difficult to know where a passage precisely belonged. ‘Never fold the napkin (there is no need, I feel sure, to put the unspeakable “serviette” in its place), but drop it lightly on the table.’ Nicola listed this under ‘Table Manners’, and wondered if Mr Period would find the phrase ‘refeened’, a word he often used with humorous intent.

She looked up to find him in a trance, his pen suspended, his gaze rapt, a sheet of headed letter-paper under his hand. He caught her glance and said: ‘A few lines to my dear Desirée Bantling. Soi-disant. The Dowager, as the Press would call her. You saw Ormsbury had gone, I dare say?’

Nicola, who had no idea whether the Dowager Lady Bantling had been deserted or bereaved, said: ‘No, I didn’t see it.’

‘Letters of condolence!’ Mr Period sighed with a faint hint of complacency. ‘How difficult they are!’ He began to write again, quite rapidly, with sidelong references to his note-pad.

Upstairs a voice, clearly recognizable, shouted angrily: ‘– and all I can say, you horrible little man, is I’m bloody sorry I ever asked you.’ Someone came rapidly downstairs and crossed the hall. The front door slammed. Through her window, Nicola saw her travelling companion, scarlet in the face, stride down the drive, angrily swinging his bowler.

‘He’s forgotten his umbrella,’ she thought.

‘Oh, dear!’ Mr Period murmured. ‘An awkwiddity, I fear me. Andrew is in one of his rages. You know him, of course.’

‘Not till this morning.’

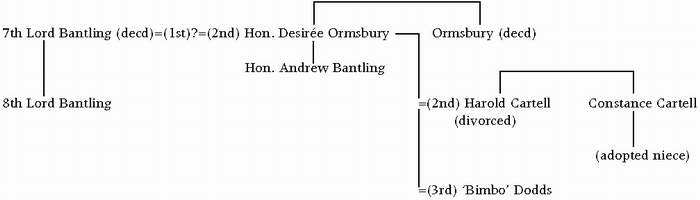

‘Andrew Bantling? My dear, he’s the son of the very Lady Bantling we were talking about. Desirée you know. Ormsbury’s sister. Bobo Bantling – Andrew’s papa – was the first of her three husbands. The senior branch. Seventh Baron. Succeeded to the peerage –’ Here followed inevitably, one of Mr Period’s classy genealogical digressions. ‘My dear Nicola,’ he went on, ‘I hope, by the way, I may so far take advantage of a family friendship?’

‘Please do.’

‘Sweet of you. Well, my dear Nicola, you will have gathered that I don’t vegetate all by myself in this house. No. I share. With an old friend who is called Harold Cartell. It’s a new arrangement and I hope it’s going to suit us both. Harold is Andrew’s step-father and guardian. He is, by the way, a retired solicitor. I don’t need to tell you about Andrew’s mum,’ Mr Period added, strangely adopting the current slang. ‘She, poor darling, is almost too famous.’

‘And she’s called Desirée, Lady Bantling?’

‘She naughtily sticks to the title in the teeth of the most surprising remarriage.’

‘Then she’s really Mrs Harold Cartell?’

‘Not now. That hardly lasted any time. No. She’s now Mrs Bimbo Dodds. Bantling. Cartell. Dodds. In that order.’

‘Yes, of course,’ Nicola said, remembering at last the singular fame of this lady.

‘Yes. ‘Nuff said,’ Mr Period observed, wanly arch, ‘under that heading. But Hal Cartell was Lord Bantling’s solicitor and executor and is the trustee for Andrew’s inheritance. I, by the way, am the other trustee and I do hope that’s not going to be diffy. Well, now,’ Mr Period went cosily on, ‘on Bantling’s death, Hal Cartell was also appointed Andrew’s guardian. Desirée at that time, was going through a rather farouche phase and Andrew narrowly escaped being made a Ward-in-Chancery. Thus it was that Hal Cartell was thrown in the widow’s path. She rather wolfed him up, don’t you know? Black always suited her. But they were too dismally incompatible. However, Harold remained, nevertheless, Andrew’s guardian and trustee for the estate. Andrew doesn’t come into it until he’s twenty-five: in six months’ time, by the way. He’s in the Brigade of Guards, as you’ll have seen, but I gather he wants to leave in order to paint, which is so unexpected. Indeed, that may be this morning’s problem. A great pity. All the Bantlings have been in the Brigade. And if he must paint, poor dear, why not as a hobby? What his father would have said – !’ Mr Period waved his hands.

‘But why isn’t he Lord Bantling?’

‘His father was a widower with one son when he married Desirée. That son of course, succeeded.’

‘Oh, I see,’ Nicola said politely. ‘Of course.’

‘You wonder why I go into all these begatteries, as I call them. Partly because they amuse me and partly because you will, I hope, be seeing quite a lot of my stodgy little household and, in so far as Hal Cartell is one of us, we – ah – we overlap. In fact,’ Mr Period went on, looking vexed, ‘we overlap at luncheon. Harold’s sister, Connie Cartell, who is our neighbour, joins us. With – ah – with a protégée, a – soi-disant niece, adopted from goodness knows where. Her name is Mary Ralston and her nickname, an inappropriate one, is Moppett. I understand that she brings a friend with her. However! To return to Desirée. Desirée and her Bimbo spend a lot of time at the dower house, Baynesholme, which is only a mile or two away from us. I believe Andrew lunches there today. His mother was to pick him up here and I do hope he hasn’t gone flouncing back to London: it would be too awkward and tiresome of him, poor boy.’

‘Then Mrs Dodds – I mean Lady Bantling and Mr Cartell still –?’

‘Oh, lord, yes! They hob-nob occasionally. Desirée never bears grudges. She’s a remarkable person. I dote on her but she is rather a law unto herself. For instance, one doesn’t know in the very least how she’ll react to the death of Ormsbury. Brother though he is. Better, I think, not to mention it when she comes, but simply to write – But there, I really mustn’t bore you with all my dim little bits of gossip. To work, my child! To work!’

They returned to their respective tasks. Nicola had made some headway with the notes when she came upon one which was evidently a rough draft for a letter. ‘My dear –’ it began, ‘What can I say? Only that you have lost a wonderful’ – here Mr Period had left a blank space – ‘and I, a most valued and very dear old friend.’ It continued in this vein with many erasures. Should she file it under ‘The Compleat Letter-Writer’? Was it in fact intended as an exemplar?

She laid it before Mr Period.

‘I’m not quite sure if this belongs.’

He looked at it and turned pink. ‘No, no. Stupid of me. Thank you.’

He pushed it under his pad and folded the letter he had written, whistling under his breath. ‘That’s that,’ he said, with rather forced airiness. ‘Perhaps you will be kind enough to post it in the village.’

Nicola made a note of it and returned to her task. She became aware of suppressed nervousness in her employer. They went through the absurd pantomime of catching each other’s eyes and pretending they had done nothing of the sort. This had occurred two or three times when Nicola said: ‘I’m so sorry. I’ve got the awful trick of staring at people when I’m trying to concentrate.’

‘My dear child! No! It is I who am at fault. In point of fact,’ Mr Period went on with a faint simper, ‘I’ve been asking myself if I dare confide a little problem.’

Not knowing what to say, Nicola said nothing. Mr Period, with an air of hardihood, continued. He waved his hand.

‘It’s nothing. Rather a bore, really. Just that the – ah – the publishers are going to do something quite handsome in the way of illustrations and they – don’t laugh – they want my old mug for their frontispiece. A portrait rather than a photograph is thought to be appropriate and, I can’t imagine why, they took it for granted one had been done, do you know? And one hasn’t.’

‘What a pity,’ Nicola sympathized. ‘So it will have to be a photograph.’

‘Ah! Yes. That was my first thought. But then, you see – They made such a point of it – and I did just wonder – My friends, silly creatures, urge me to it. Just a line drawing. One doesn’t know what to think.’

It was clear to Nicola that Mr Period died to have his portrait done and was prepared to pay highly for it. He mentioned several extremely fashionable artists and then said suddenly: ‘It’s naughty of dear Agatha Troy to be so diffy about who she does. She said something about not wanting to abandon bone for bacon, I think, when she refused – she actually refused to paint –’

Here Mr Period whispered an extremely potent name and stared with a sort of dismal triumph at Nicola. ‘So she wouldn’t dream of poor old me,’ he cried. ‘’Nuff said!’

Nicola began to say: ‘I wonder, though. She often –’ and hurriedly checked herself. She had been about to commit an indiscretion. Fortunately Mr Period’s attention was diverted by the return of Andrew Bantling. He had reappeared in the drive, still walking fast and swinging his bowler, and with a fixed expression on his pleasantly bony face.

‘He has come back,’ Nicola said.

‘Andrew? Oh, good. I wonder what for.’

In a moment they found out. The door opened and Andrew looked in.

‘I’m sorry to interrupt,’ he said loudly, ‘but if it’s not too trouble-some, I wonder if I could have a word with you, P.P.?’

‘My dear boy! But, of course.’

‘It’s not private from Nicola,’ Andrew said. ‘On the contrary. At the same time, I don’t want to bore anybody.’

Mr Period said playfully: ‘I myself have done nothing but bore poor Nicola. Shall we “withdraw to the withdrawing-room” and leave her in peace?’

‘Oh. All right. Thank you. Sorry.’ Andrew threw a distracted look at Nicola and opened the door.

Mr Period made her a little bow. ‘You will excuse us, my dear?’ he said and they went out.

Nicola worked on steadily and was only once interrupted. The door opened to admit a small, thin, querulous-looking gentleman who ejaculated: ‘I beg your pardon. Damn!’ and went out again. Mr Cartell, no doubt.

At eleven o’clock Alfred came in with sherry and biscuits and Mr Period’s compliments. If she was in any difficulty would she be good enough to ring and Alfred would convey the message. Nicola was not in any difficulty, but while she enjoyed her sherry she found herself scribbling absent-mindedly.

‘Good lord!’ she thought. ‘Why did I do that? A bit longer on this job and I’ll be turning into a Pyke Period myself.’

Two hours went by. The house was very quiet. She was half-aware of small local activities: distant voices and movement, the rattle and throb of machinery in the lane. She thought from time to time of her employer. To which brand of snobbery, that overworked but always enthralling subject, did Mr Pyke Period belong? Was he simply a snob of the traditional school who dearly loves a lord? Was he himself a scion of ancient lineage; one of those old, uncelebrated families whose sole claim to distinction rests in their refusal to accept a title? No. That didn’t quite fit Mr Period. It wasn’t easy to imagine him refusing a title and yet –

Her attention was again diverted to the drive. Three persons approached the house, barked at and harassed by Pixie. A large, tweedy, middle-aged woman with a red face, a squashed hat and a walking-stick, was followed by a pale girl with fashionable coiffure and a young man who looked, Nicola thought, quite awful. These two lagged behind their elder who shouted and pointed with her stick in the direction of the excavations. Nicola could hear her voice, which sounded arrogant, and her gusts of boisterous laughter. While her back was turned, the girl quickly planted an extremely uninhibited kiss on the young man’s mouth.

‘That,’ thought Nicola, ‘is a full-treatment job.’

Pixie floundered against the young man and he kicked her rapidly in the ribs. She emitted a howl and retired. The large woman looked round in concern but the young man was smiling damply. They moved round the corner of the house. Through the side window Nicola could see them inspecting the excavations. They returned to the drive.

Footsteps crossed the hall. Doors were opened. Mr Cartell appeared in the drive and was greeted by the lady who, Nicola saw, resembled him in a robust fashion. ‘The sister,’ Nicola said. ‘Connie. And the adopted niece, Moppett, and the niece’s frightful friend. I don’t wonder Mr Period was put out.’

They moved out of sight. There was a burst of conversation in the hall, in which Mr Period’s voice could be heard, and a withdrawal (into the ‘withdrawing-room’, no doubt). Presently Andrew Bantling came into the library.

‘Hallo,’ he said. ‘I’m to bid you to drinks. I don’t mind telling you it’s a bum party. My bloody-minded step-father, to whom I’m not speaking, his bully of a sister, her ghastly adopted what-not and an unspeakable chum. Come on.’

‘Do you think I might be excused and just creep in to lunch?’

‘Not a hope. P.P. would be as cross as two sticks. He’s telling them all about you and how lucky he is to have you.’

‘I don’t want a drink. I’ve been built up with sherry.’

‘There’s tomato juice. Do come. You’d better.’

‘In that case –’ Nicola said and put the cover on her typewriter.

‘That’s right,’ he said and took her arm. ‘I’ve had such a stinker of a morning: you can’t think. How have you got on?’

‘I hope, all right.’

‘Is he writing a book?’

‘I’m a confidential typist.’

‘My face can’t get any redder than it’s been already,’ Andrew said and ushered her into the hall. ‘Are you at all interested in painting?’

‘Yes. You paint, don’t you?’

‘How the hell did you know?’

‘Your first fingernail. And anyway, Mr Period told me.’

‘Talk, talk, talk!’ Andrew said, but he smiled at her. ‘And what a sharp girl you are, to be sure. Oh, calamity, look who’s here!’

Alfred was at the front door, showing in a startling lady with tangerine hair, enormous eyes, pale orange lips and a general air of good-humoured raffishness. She was followed by an unremarkable, cagey-looking man, very much her junior.

‘Hallo, Mum!’ Andrew said. ‘Hallo, Bimbo.’

‘Darling!’ said Desirée Dodds or Lady Bantling. ‘How lovely!’

‘Hi,’ said her husband, Bimbo.

Nicola was introduced and they all went into the drawing-room.

Here, Nicola encountered the group of persons with whom, on one hand disastrously and on the other to her greatest joy, she was about to become inextricably involved.

CHAPTER 2

Luncheon

Mr Pyke Period made much of Nicola. He took her round, introducing her to Mr Cartell and all over again to ‘Lady Bantling’ and Mr Dodds; to Miss Connie Cartell and, with a certain lack of enthusiasm, to the adopted niece, Mary or Moppett, and her friend, Mr Leonard Leiss.

Miss Cartell shouted: ‘Been hearing all about you, ha, ha!’

Mr Cartell said: ‘Afraid I disturbed you just now. Looking for P.P. So sorry.’

Moppett said: ‘Hallo. I suppose you do shorthand? I tried but my squiggles looked like rude drawings. So I gave up.’ Young Mr Leiss stared damply at Nicola and then shook hands: also damply. He was pallid and had large eyes, a full mouth and small chin. The sleeves of his violently checked jacket displayed an exotic amount of shirt-cuff and link. He smelt very strongly of hair oil. Apart from these features it would have been hard to say why he seemed untrustworthy.

Mr Cartell was probably by nature a dry and pedantic man. At the moment he was evidently much put out. Not surprising, Nicola thought, when one looked at the company: his step-son, with whom, presumably, he had just had a flaring row, his divorced wife and her husband, his noisy sister, her ‘niece’ whom he obviously disliked, and Mr Leiss. He dodged about, fussily attending to drinks.

‘May Leonard fix mine, Uncle Hal?’ Moppett asked. ‘He knows my kind of wallop.’

Mr Period, overhearing her, momentarily closed his eyes and Mr Cartell saw him do it.

Miss Cartell shouted uneasily: ‘The things these girls say, nowadays! Honestly!’ and burst into her braying laugh. Nicola could see that she adored Moppett. Leonard adroitly mixed two treble Martinis.

Andrew had brought Nicola her tomato juice. He stayed beside her. They didn’t say very much but she found herself glad of his company.

Meanwhile, Mr Period, who it appeared, had recently had a birthday, was given a present by Lady Bantling. It was a large brass paper-weight in the form of a fish rampant. He seemed to Nicola to be disproportionately enchanted with this trophy and presently she discovered why.

‘Dearest Desirée,’ he exclaimed. ‘How wonderfully clever of you: my crest, you know! The form, the attitude, everything! Connie! Look! Hal, do look.’

The paper-weight was passed from hand to hand and Andrew was finally sent to put it on Mr Period’s desk.

When he returned Moppett bore down upon him. ‘Andrew!’ she said. ‘You must tell Leonard about painting. He knows quantities of potent dealers. Actually, he might be jolly useful to you. Come and talk to him.’

‘I’m afraid I wouldn’t know what to say, Moppett.’

‘I’ll tell you. Hi, Leonard! We want to talk to you.’