Полная версия:

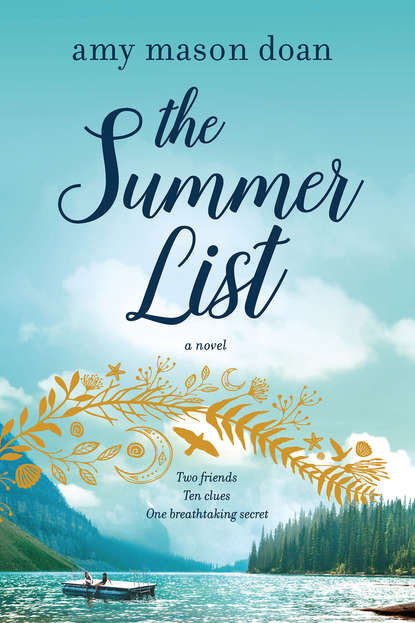

The Summer List

“Yes, Case.”

I walked slowly to the end of the dock until I stood over her left shoulder, so close I could see the messy part in her hair. It was a darker red now.

The greetings I’d rehearsed, the lines and alternate lines and backup-alternate lines, had abandoned me. They’d sailed away, carried off by the breeze when I wasn’t paying attention.

But Casey spoke first, her eyes on the water. “You’ve been standing back there forever. I thought you were going to leave.”

“I almost did.”

She tilted her head up to look at me. Scanning, evaluating, and, finally, delivering her report—“You’re still you.”

Her face was a little thinner, her skin less freckled. There was something behind her eyes, a weariness or skepticism, that hadn’t been there when we were girls.

I forced a smile. “And you’re still you.”

I got, in return, no smile. And silence.

Casey made no move to get up, so I fumbled on. “And the house is still...”

“Weird,” she finished.

“I was going to say something like charming.”

“Charming? Laura doesn’t say charming. Tell me Laura has not grown up into someone who says charming.”

She wasn’t going to make this easy. I’d thought, from the cheerful humility of her invitation, that she’d at least try. When I didn’t answer, Casey swiveled her body to look back at the house, as if to evaluate it through fresh eyes the way she’d examined me.

“We haven’t done much. That tiny addition on the east side. And I managed to put in a full bath upstairs finally. It’s yours this weekend, along with my old bedroom.”

“I was going to say. I had to bring my dog. I thought it’d be crowded with all of us, Alex and your little girl and my dog. She’s kind of big, and she’s sweet with kids, but she could knock a little one down... I don’t know how old your girl is but...”

Casey looked up at me but let me stumble on.

“Anyway there wasn’t anybody renting our old place this weekend, so I’ll sleep there...”

The truth was my place had been booked solid all summer, so I’d bumped out this weekend’s renters. Some sweet family that had reserved months ago. Other property owners kicked people out all the time when they wanted to use their houses instead, and my property manager grumbled about it, but I’d never done it before. I’d felt so guilty I’d spent hours finding them another place and paid the $230 difference.

Bullshit, Casey’s eyes said.

She knew the truth: I couldn’t bear staying with her. Tiptoeing around politely in the familiar rooms where we’d once been careless and easy as sisters. But I went on, elaborating on my story—the sure sign of a lie. “Of course I couldn’t put you out...”

“‘Put you out,’” she said. “Grown-up Laura says ‘put you out’?”

I didn’t understand it, the utter disconnect between her warm, silly, lovable letter, the Casey I’d first met, and the person who was sitting here next to me, making everything a hundred times harder than it had to be.

Would the running commentary last all weekend? Laura eats with her fork and knife European-style, now. Grown-up Laura prefers red wine to white. Laura wears cuff bracelets now. Laura changed her perfume to L’eau D’Issey. Every little gesture picked over and mocked.

It hit with awful certainty: I shouldn’t have come.

Would it get better or worse when Alex joined us? I didn’t hate her anymore. Enough time had passed. She couldn’t help how she was.

With Alex to fill the silences, and Casey’s daughter around as a buffer, and me sleeping at my place, I’d just make it through the weekend. Less than sixty hours if I left Sunday morning instead of Sunday night, blaming traffic and work.

“Where’s your mom and your little girl? I’m sorry, I don’t know her name.”

“Elle. Off on a trip together. Tahoe.”

So much for the buffer.

Casey nodded at my old house across the lake. “Now. That one has changed, I hear. Modern everything.”

“Only the kitchen, really,” I said. “The rental company insisted. I’ve just seen pictures.” From across the shining water, I could make out the dark line of the dock, a flash of sunset on a window.

I’d planned to drive there first. Drop off Jett, compose myself, drink a glass of wine (or three, or four) to loosen up for the big reunion. If I had I could have kayaked over to Casey’s instead of driving.

And paddled away again the second I realized how she was going to be.

“You haven’t gone inside?” she said. “Not once?”

I shook my head. “I can do everything online. It’s crazy.”

“I thought maybe you were sneaking back at night. Hiding out in the house, staying off the lake, calling your groceries in. To avoid seeing me.”

“I wouldn’t do that.”

She narrowed her eyes. “You didn’t sell it, though.”

The “why?” was there in her expression, daring me, but I didn’t have an answer. I’d always planned to sell the house. My mother didn’t care either way, and we got offers. Every year, I considered it. But I never went through with it.

I met her stare for a minute before I had to look away. My eyes landed on a spot in the lake about ten yards from the edge of the dock. I didn’t mean to look there. Maybe there was a tiny ripple from a fish, or a point in the sunset’s reflection that was a more burnished gold than the surrounding water.

She followed my gaze. And for the first time, her voice softened. “Strange to think it’s still there. After so long.”

“It’s not. It’s crumbled into a million pieces or floated away.”

Casey shook her head. “No. It’s still there.”

“How do you know?”

“I just do. I feel it in my bones.”

“That sounds like something your mom would say. Used to say.”

She tilted her head, thinking. “God. It does.”

She pulled her knees close to her body and rested her right cheek on them, then looked up at me with a funny little lopsided smile.

There was enough of the Casey I remembered in that smile that I returned it.

I sat next to her, wrapping my coat tighter, my legs dangling off the edge of the dock. It felt strange, to sit like that with shoes and pants on. I should be in my old cargo shorts, dipping my bare feet in the water.

For a minute we watched the quivering red-and-gold shapes on the lake. Then I felt the gentle weight of her hand on my shoulder.

“Don’t mind my flails, grown-up Laura,” she said. “Grown-up Casey is doing her best. She’s missed you.”

The words stuck in my throat, and when they finally came out, they were rough. My eyes on the auburn lake, I reached up to clutch her hand—one quick, fumbling squeeze.

“I’ve missed you, too, Case.”

2

Ariel and Pocahontas

June 1995

Summer before freshman year

The fourth day of summer started exactly like the first three.

A second of dread when I woke up, followed by a rush of relief when I remembered it was vacation. Then the quick, glorious tally—no school for eighty-eight days. And finally the smell of vanilla floating down the hall. Yesterday it had been crumb cake, the day before it was muffins, so today was probably French toast. My favorite.

I got dressed fast, changing from my nightgown into my summer uniform: a big T-shirt and cargo shorts.

The last part of my routine was too important to be rushed. I transferred a small, silvery-gray object from under my pillow to the Ziploc I kept on my nightstand, made sure it was sealed to the last millimeter, then slipped it into my lower-right shorts pocket, the only one with a zipper. Where it always went.

Then I had the entire day free to explore the lake. French toast, and no Pauline Knowland or Suzanne Farina asking me what my bra size was up to in honeyed tones, or calling me Sister Christian just within earshot, and the whole day free. Bliss.

It only lasted the length of the hallway.

“You’ll bring that to the new neighbors after breakfast,” my mother said when I entered the kitchen. She was scrambling eggs with a rubber spatula, and she paused to point it at a pound cake on the counter. “Good morning.”

Chore assignment first, greeting second. This about summed up my mother.

She went back to parting the sea of yellow in the pan.

So not only was the vanilla smell for some other family, I had an assignment. I examined the cake’s golden surface. It was perfect, but curiously plain. No nuts, no chocolate chips, no blueberries. Not even drizzled with glaze, and it obviously wouldn’t be. My mother always poured the cloudy liquid on when her cakes were still piping hot.

Next to the naked cake she’d set out a paper plate, Saran Wrap, a length of red ribbon, and one of her monogrammed notecards. A complete new-neighbor greeting kit, ready to go before 7:30 a.m. I read the card silently. Welcome—Christies.

A stingy sort of note, nothing like the warm introduction she’d written when the Daytons moved in down the shore last year. That had included an invitation to church. Surely my mother could have spared a few more words for the new family, a the before our last name. They were right across the narrowest part of the lake from us. If they had binoculars, they could see how much salt we put on our eggs.

It seemed she’d already taken a dislike to the new people, and I set about learning why. “You’re not coming with me to meet them?”

“They have a daughter your age, you need to offer to walk to school together the first day,” she said, like this was written in stone somewhere.

Shoot me now. The last thing I needed was more complications at school. My plan was to lie low in September.

I watched the tip of my mother’s white spatula make figure eights in the skillet. How could eggs be so nasty on their own when they played a clutch role in French toast? I’d take a tiny spoonful and distribute it artfully around my plate so it would look like more.

As if she’d heard my thoughts, my mother mounded a triple lumberjack serving of scrambled eggs onto a plate and handed it to me.

I carried it to the breakfast nook and sat next to my dad, who was hidden behind his newspaper. I could only see his tuft of white hair. It was sticking up vertically, shot through with sun from the window. “Last one awake is the welcome wagon,” he said. “New household rule.”

He snapped a corner of the paper down and winked at me. “Morning.”

I smiled. “Morning.”

I pushed egg clumps around with my fork and stared out the window at the small brown shape in the pines across the lake. The junky-looking old Collier place, the one everybody called The Shipwreck. The Collier name was legend around Coeur-de-Lune, though the actual Colliers were long gone. They’d been rich, and a lot of them had died young. The small building across the lake where the Collier kids slept in summer had been falling apart since before I was born, and my mother always said they should just burn it. The Colliers’ main summerhouse, the fancy three-story one that had once been a few hundred yards up the shore, had been torn down when the land was split up decades before.

I’d seen trucks at The Shipwreck since it sold. Pedersen’s Hardware and Ready Windows. I loved the funny little house exactly the way it was, and now the new family would fix it up and ruin it.

So because they had a daughter my age my mother was totally blowing off the visit? Something was off. In her world of social niceties, frozen somewhere around 1955, new neighbors required baked goods. Not from a mix—new neighbors called for separating yolks from whites. And they definitely called for a personal appearance.

“Saw their car the other day when they were moving in,” my dad said behind his New York Times, making it shiver. There was a photo of Bill Clinton on the front page, shaking some dignitary’s hand, and when he spoke it looked like they were dancing.

My mother was transferring patty sausages from a skillet onto a plate. At his words, her elbows really got into stabbing the sausages and violently shaking them off the fork.

When she didn’t respond he continued, “Saw what was on the back bumper.”

That did it.

She dropped the plate between us with a thud and stalked into the dining room to tend to her latest batch of care packages for soldiers. They were arranged in a perfect ten-by-ten grid on the dining room table.

I forked a sausage and took a bite, burning the roof of my mouth with spicy grease.

After I swallowed I whispered, “What was on the car?” Maybe a bumper sticker my mother considered racy. Or inappropriate, to use one of her favorite words.

The day wasn’t blissfully free anymore, but at least it was getting interesting.

A new girl my age, just across the water, with parents who’d slapped an inappropriate bumper sticker on the family wagon. Maybe one of those Playboy women with arched backs and waists as tiny as their ankles, the ones truck drivers liked to keep on their mud flaps.

My dad set his paper down and started working the crossword. He did the puzzle in the Times only after finishing the easier ones in the Reno Statesman and the Tahoe Daily Journal. I liked to watch his forehead lines jump around when he worked on the Times crossword. I could tell when it was going well and when he was stumped, just by how wavy they were in the center.

He tapped on the paper with the tip of his black ballpoint the way he always did when he was struggling. He must have thrown in one or two extra taps because I glanced down. Above the “Across” clues he’d drawn a fish with legs. Ah. That would do it. According to my mother’s complicated book of social equations, one of those pro-Darwin anti-Christian fish with legs on your rear bumper meant you got a red ribbon, but only tied around a no-frills pound cake, and you got a duty visit from her daughter, but not from her.

My dad scribbled over the drawing and cleared his throat, then sent me a quick wink. I nudged my scrambled-egg plate closer to him and he took care of them for me in three bites, one eye on the dining room entryway as he chewed.

He went back to his crossword, and I got up to wrap the cake, curling the ribbon to make up for the terrible note. The unwelcome note. But as I was returning the scissors to the drawer I saw the black pen my mother had used. I’d mastered her handwriting years before. (Please excuse Laura from Physical Education, her migraines have been simply terrible lately.)

Quickly, expertly, I revised her words.

Welcome—Christies became Welcome!!—The Christies. We’re so thrilled you’re here!

Okay, maybe I went overboard. It was the kind of note Pauline Knowland’s and Suzanne Farina’s mothers would write, a message anticipating years of squealing hellos at Back-to-School night.

I tucked the note in my pocket, returned the pen to the drawer, and by the time my mother bustled in again I was at the table sipping orange juice, innocent as anything.

* * *

I dipped my paddle, breaking the glassy surface of the lake. I was the only one out on the water this early—the only human at least. The gentle ploshes and chirps and ticks of the lake felt like solitude; I knew them so well.

It was chilly on the water but warmth spread through my shoulders as I set my short course for The Shipwreck. My dad liked to speak in jaunty nautical terms like this; he always asked when I came home after a day on the lake—How was your voyage? Or—Duel with any pirates?

He gave me my kayak for my tenth birthday. My mother was just as surprised as me when he led us outside after the German chocolate cake. I’d opened up all my other gifts—two sweaters and six books and a Schumann CD I’d requested and a tin of Violetta dusting powder with a massive puff I’d not only not requested, but had absolutely no clue what to do with. My mother and I both thought the birthday was done.

Then he’d said, Might be one more thing outside.

He’d covered his surprise with a black tarp, pulling it off to reveal the sleek yellow vessel. So you can explore, he’d explained.

To my quietly fuming mother, he had said, his eyes dodging hers, Because she’s in the double digits now.

If they fought about it later—him writing such a big check without asking or, the more serious offense, the implication that he knew me best—I hadn’t heard it, and the heating duct in our small house ran right from their bedroom up to mine. I heard their whispered “discussions” all the time.

Eventually my mother grew to accept the kayak. She told her church friends that she liked me to play outdoors all summer. Sermons in stones and all of that.

The lake was small, a crescent of water only six miles around. At the narrowest, southernmost point, where we were, it was only four hundred feet wide. I could paddle across our end in two minutes without breaking a sweat.

Today I took it easy so I could size up the new neighbors as I crossed. I expected them to be outside commanding an army of painters and fix-it people, but the place seemed as run-down as ever, the gutters overflowing with pine needles, the dull wood shingles fringed in moss, the narrow dock as rickety as a gangplank. Whatever the trucks had been there for, it wasn’t visible from the back.

The house hadn’t been rented in more than six months. We were too far from the good skiing and stores, and you couldn’t take anything motorized on our little lake. Everybody wanted to live in Tahoe, or at least Pinecrest.

But there were signs of life. A rainbow beach towel draped over the dock ladder, bags of mulch stacked by the garden gate. The small square garden, to the left of the house, had been untended for years and used unofficially as a dog run. It was basically an ugly, deer-proof metal fence surrounding weeds, but obviously the new owners had plans.

Something else new—a small red spot on the edge of the dock, right at the center. Paddling closer, I saw that it was a kid’s figurine dangling from a nail. A plastic Ariel, from The Little Mermaid, her chest puffed out like when she was on the prow of the ship pretending to be a statue. It definitely had not been there the last time I’d snooped around The Shipwreck.

I wondered if the famous “daughter my age” had done it. I hoped not. It was the kind of joke I liked, and I didn’t want to like her. There was no way we would be friends, not when she found out what I was at school. The best I could hope for was that she would be what I called a Neutral. Someone I didn’t need to think about at all. Someone who didn’t make my day better or worse.

“You look exactly like an Indian princess.”

I jumped in my seat, almost losing my paddle.

A girl was swimming up to me. Her pale skin had splatters of mud on it and she had threads of green lake gunk in her hair. Red hair. The toy Ariel on the dock had definitely been her idea.

“You know, like Pocahontas or someone, with your dark braid, in your canoe?” she continued, breaststroking close enough that I could see it was freckles on her shoulders, not dirt. I’d never seen so many freckles. There were goose bumps, too, which didn’t surprise me. The lake wasn’t really comfortable for swimming until after the Fourth of July.

I composed myself enough to correct her. “Kayak.”

“Right, canoes are the kneeling ones. You coming to see us?” She tilted her head at the house.

Before I could answer, she closed her eyes and sank down into the water up to her hairline. When she popped back up, she squeezed her nostrils between her thumb and index finger to clear them.

“My mother wanted me to bring you this,” I said. I stashed my paddle in the nose of the kayak, yanked my backpack from the front seat, and unzipped it so she could see the cake under its pouf of plastic wrap. “To welcome you and your parents.”

“Parent. Singular. So you didn’t want to bring it? Your mom made you?”

I still wasn’t sure what category she belonged to, but she was definitely not a Neutral.

“I didn’t mean that,” I said.

I was starting to drift from the dock but she swam close and for a second I worried she would grab the hull and capsize me.

At the thought, I automatically gripped my shorts pocket, squeezing the familiar shape, smaller than a deck of cards, through the worn cotton. The Ziploc was only insurance. My good-luck charm couldn’t get wet.

The swimming girl’s eyes darted from my face down to the edge of my shorts, where my hand clutched. She cleared water from her ears, repositioned her purple bathing suit straps, and slicked her red hair back with both hands.

The whole time she performed this aquatic grooming routine, her eyes didn’t budge from my right hand. I forced myself to let go of my pocket and fidgeted with my braid instead.

But her eyes didn’t follow my hand. They stayed right on the zippered compartment of my shorts.

I’d have to invent a new category for this girl. She missed nothing.

I would set the cake on the dock. I’d paddle over to Meriwether Point like I’d planned and have my picnic. Lie in the sun as long as I wanted, with nobody to bug me, on my favorite spot on the big rock that curved perfectly under my back. Later I’d collect pieces of driftwood for a mirror I was making and go swimming in Jade Cove.

I had all kinds of plans for the summer.

“Well, I’ve got to...” I began.

“Do you want to...” She laughed. “What were you saying?”

“Just that I should go. I told my mom I’d help around the house.”

“Where’s your place?”

I pointed.

She paddled herself around to face the opposite shore. “Cool. We can swim that, easy. We can go back and forth all the time.”

She was so sure we’d be friends. She was sure enough for both of us.

“Come in and we’ll eat the whole cake ourselves,” she said, completing her circle in the water to face me. “My mom’s in Tahoe. She won’t be back ’til late.”

“I wish I could.” Stop being so nice. I can’t afford to like you.

“Are you going to be in ninth?” she went on, panting a little as she tread water.

“Yeah.”

“Me, too. You can say you were telling me about the high school. That’s helpful.”

“There’s not much to tell about the school. It’s tiny. It’s not very good. The football team is the Astros, because everyone around here is seriously into the moon thing.”

“See? I need you. Come on.”

I didn’t offer the most valuable piece of advice—If you want to make friends at CDL High, don’t hang around with me.

“Please. Tell your mom I totally forced you to eat a piece of cake and help me unpack.” The girl grinned, sure of her charm.

It was a wide grin that stretched out the freckles on her nose, and I couldn’t resist it.

* * *

Her name was Casey.

“Casey Katherine Shepherd, named after Casey Kasem, that old DJ,” she said, sprinting ahead of me up the dock to her house. She wrapped the rainbow beach towel around her bottom half as she ran. “My mom was obsessed with him,” she called back, leaping onto the sandy path in the sloping, scrubby patch of lawn behind the house. “She has CD box sets of radio countdowns from 1970 to 1988. What’s your name?”

“Laura. Named after a great-great-aunt I never met. But I’m guessing she wasn’t a DJ.”

Casey turned so I could see she was laughing, but she didn’t stop running. She didn’t rinse her feet off, though there was a faucet right there by the back door, but pounded up the rotting wood steps, opened the screen door, and walked inside, tracking muck.

I’d always wanted to go inside The Shipwreck. When I was little, I’d imagined wood walls, hammocks, ropes dangling from the ceiling. Maybe a captain’s wheel.

But it was only an ordinary room crammed with moving boxes. The small windows and dark green paint made everything gloomy.