Полная версия:

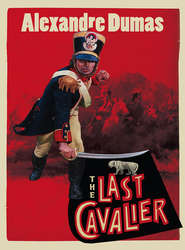

The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon

During the balls he attended, Sainte-Hermine would stand coldly and impassibly at some bay window or in a corner of the room. In that, he became an object of bewilderment for all the gay young women who wondered what secret vow might be depriving them of such an elegant dance partner—for he always dressed with such taste in the latest style.

Claire had wondered, too, at Sainte-Hermine’s reserve in her presence, especially since her mother seemed to admire the young man greatly. She spoke as highly about his family, decimated by the Revolution, as she did of him, and she knew that money could not be an obstacle to their union. The substantial fortunes of the two families were roughly equal.

One can understand the impression the mysterious young Sainte-Hermine might make on a young girl’s heart, especially on a young Creole girl’s heart, with the combination of his physical features and moral qualities, his elegance and strength. Claire’s image of him occupied her mind while biding its time to take over her heart.

Hortense made her hopes and desires clear to Claire: She wanted to marry Duroc, whom she loved, rather than Louis Bonaparte, whom she did not—that essentially was the secret she whispered to her friend. But it was not the same, for Claire’s storybook passion made it difficult for her to speak quite so plainly. At the same time that she described Hector’s features in great detail to her friend, she tried also to understand as best she could the shadows surrounding him.

Finally, after Claire’s mother had called twice, after she had stood up and embraced Hortense, as if the idea had just come to mind—as Madame de Sévigné observes, the most important part of a letter is in the postscript—she said: “By the way, dear Hortense, I am forgetting to ask you something.”

“What is that?”

“I understand that Madame de Permon is giving a great ball.”

“Yes. Loulou came to see my mother and me and invited us herself.”

“Are you going?”

“Yes, of course.”

“My dear Hortense,” Claire said in her most endearing voice, “I would like to ask a favor.”

“A favor?”

“Yes. Get an invitation for my mother and me. Is that possible?”

“Yes, I think so.”

Claire leaped with a joy. “Oh, thank you!” she said. “How will you go about it?”

“Well, I could ask Loulou for an invitation. But I prefer having Eugene do it. Eugene is close to Madame de Permon’s son, and Eugene will ask him for what you desire.”

“And I shall go to Madame de Permon’s ball?” cried Claire joyously.

“Yes,” Hortense answered. Then, looking her young friend in the eye, she asked, “Will he be there?”

Claire turned as red as a beet and dropped her eyes. “I think so.”

“You will point him out to me, won’t you?”

“Oh! You’ll recognize him without me doing that, my dear Hortense. Have I not told you that he can be picked out from among a thousand?”

“How sorry I am that he is not a dancer!” said Hortense.

“How do you think I feel?”

The two girls kissed each other and parted, Claire reminding Hortense not to forget the invitation.

Three days later Claire de Sourdis received her invitation by mail.

XI Madame de Permon’s Ball

THE BALL FOR WHICH Mademoiselle Hortense de Beauharnais’s young friend had requested an invitation was the social event of the season for all of fashionable Paris. Madame de Permon would have needed a mansion four times the size of her own to welcome all those eager to attend, and she had refused to issue further invitations to more than one hundred men and more than fifty women despite their ardent requests. But, because she had been born in Corsica and linked from childhood to the Bonaparte family, she agreed immediately when Eugene Beauharnais made his request, and Mademoiselle de Sourdis and her mother both received their admission cards.

Madame de Permon, whose invitations were in such demand even though her name sounded a bit like the name of a commoner, was one of the grandest women of the times. Indeed, she was a descendant of the Comnène family, which had given six emperors to Constantinople, one to Heraclea, and ten to Trebizond. Her ancestor Constantin Comnène, fleeing the Muslims, had found refuge first in the Taygetus mountains and later on the island of Corsica. Along with three thousand of his compatriots who followed him as their chief, he settled there after buying from the Genoa senate the lands of Paomia, Salogna, and Revinda.

In spite of her imperial origins, Mademoiselle de Comnène fell in love with and married a handsome commoner whom people called Monsieur de Permon. Monsieur de Permon had died two years earlier, leaving his widow with a son of twenty-eight, a daughter of fourteen, and an annuity of twenty-five thousand pounds.

Madame de Permon’s high birth and her common marriage were reflected in her salon, which she opened to prominent figures in both the old aristocracy and the young democracy. Among officers in the new military and notables in the arts and sciences were names that would soon rival the most illustrious of those in the old monarchy. So it was that in her salon you could meet Monsieur de Mouchy and Monsieur de Montcalm, the Prince de Chalais, the two De Laigle brothers, Charles and Just de Noailles, the Montaigus, the three Rastignacs, the Count of Coulaincourt and his two sons Armand and August, the Albert d’Orsay family, the Montbretons. Sainte-Aulaire and the Talleyrands mingled with the Hoches, the Rapps, the Durocs, the Trénis, the Laffittes, the Dupaty family, the Junots, the Anissons, and the Labordes.

Madame de Permon’s high birth and her common marriage were reflected in her salon, which she opened to prominent figures in both the old aristocracy and the young democracy. Among officers in the new military and notables in the arts and sciences were names that would soon rival the most illustrious of those in the old monarchy. So it was that in her salon you could meet Monsieur de Mouchy and Monsieur de Montcalm, the Prince de Chalais, the two De Laigle brothers, Charles and Just de Noailles, the Montaigus, the three Rastignacs, the Count of Coulaincourt and his two sons Armand and August, the Albert d’Orsay family, the Montbretons. Sainte-Aulaire and the Talleyrands mingled with the Hoches, the Rapps, the Durocs, the Trénis, the Laffittes, the Dupaty family, the Junots, the Anissons, and the Labordes.

With her twenty-five-thousand-pound annuity Madame de Permon maintained one of Paris’s most elegant and best appointed mansions. She especially enjoyed the splendor of her flowers and plants, and her home had become a veritable greenhouse. The vestibule was so filled with potted trees and flowers that you could no longer see the walls, yet it was so skillfully illuminated with colored glass that you would have thought you were entering a fairy palace.

In those days, balls began early. By nine o’clock, Madame de Permon’s rooms were open and brightly lit, and she, her daughter Laura, and her son Albert were awaiting their guests in the salon.

Madame de Permon, still a beautiful woman, was wearing a white crepe dress, decorated with bunches of double daffodils and cut in the Greek style, with cloth draped over her breasts and held at her shoulders with two diamond clips. She had commissioned Leroy on the Rue des Petits-Champs, who was all the rage for his dresses and hats, to make her a puffy hat with white crepe and large bunches of daffodils like the ones on her dress. She wore daffodils in her jet black hair as well as in the folds of the hat, and she was holding an enormous bouquet of daffodils and violets from Madame Roux, the best florist in Paris. In each ear sparkled a diamond worth fifteen thousand francs, her only jewelry.

Mademoiselle Laura de Permon’s dress was quite simple. Her mother thought that since she was only sixteen, she should glow with her own natural beauty and not try to outshine anyone with her clothes. She was wearing a pink taffeta dress of a style similar to her mother’s, with white narcissus in a crown on her head and at the hem of her dress, along with pearl clips and earrings.

But the woman whose beauty was supposed to reign over the ball, which was being given in honor of the Bonaparte family and which the First Consul had promised to attend, was Madame Leclerc, the favorite of Madame Laetitia and her brother Bonaparte as well, so people said. To ensure her triumph, she had asked that Madame Permon allow her to dress at the mansion. She had had Madame Germon make her dress and she had arranged for Charbonnier to do her hair (he had done Madame de Permon’s as well). She woud make her entrance at the precise moment when the rooms were filling up but not yet full. That was the best moment if you wished to create a sensation and make sure you’d be seen by everyone there.

Some of the most beautiful women—Madame Méchin, Madame de Périgord, Madame Récamier—were already there when at nine thirty Madame Bonaparte, her daughter, and her son were announced. Madame de Permon rose and walked to the center of the dining room, a courtesy she had offered nobody else.

Josephine was wearing a crown of poppies and golden wheat, which also embellished her white crepe dress. Hortense too was dressed in white, her only accent being fresh violets.

At about the same time, the Comtesse de Sourdis arrived with her daughter. The countess was wearing a buttercup-yellow tunic adorned with pansies. Her daughter, whose hair was arranged in the Greek style, wore a white taffeta tunic embroidered with gold and purple. She was ravishing. Bands of gold and purple perfectly highlighted her dark hair, while a gold and purple cord accented her tiny waist.

At a signal from his sister, Eugene de Beauharnais hurried over to the new arrivals. Taking the countess’s hand, he escorted her to Madame de Permon.

Madame de Permon rose to greet the countess, then had her sit to her left; Josephine was seated on the hostess’s right. Hortense offered her arm to Claire, and they seated themselves nearby.

“Well?” Hortense asked, her curiosity getting the better of her.

“He is here,” said Claire, all atremble.

“Where?” asked Hortense eagerly.

“Well,” said Claire, “do you see where I am looking? In that group there, the man wearing the garnet-colored velvet suit, tight suede pants, and shoes with small diamond buckles. And there’s a much larger diamond buckle around the braid on his hat.”

Hortense’s eyes followed Claire’s. “Ah, you were right,” she said. “He is as handsome as Antinous. But he doesn’t look so melancholic at all. Your dark, mysterious hero is smiling at us very pleasantly.”

And indeed, the face of the Comte de Sainte-Hermine, who had not taken his eyes off Mademoiselle de Sourdis since she had entered the room, radiated inner peace and joy. When he saw Claire and her friend looking at him, he walked timidly but gracefully over to them.

“Would you be so kind, mademoiselle,” he said to Claire, “as to grant me the first quadrille or the first waltz you will be dancing?”

“The first quadrille, yes, monsieur,” Claire stammered. She had turned deathly pale when she saw the count walking toward her, and now she could feel blood rushing to her cheeks.

“As for Mademoiselle de Beauharnais,” the count, Hector, continued, bowing to Hortense, “I await the order from her lips to confirm my rank among her numerous admirers.”

“The first gavotte, monsieur, if you please,” Hortense answered, for she knew that Duroc did not dance the gavotte.

After a bow of thanks, Count Hector moved nonchalantly toward the crowd surrounding Madame de Contades, who had just arrived. Her beauty had attracted all eyes, but just then another murmur of admiration rippled through the crowd. Some new pretender to beauty’s throne had arrived. The beauty competition was now open; the dancing itself would not begin until the First Consul appeared.

It was Pauline Bonaparte—Madame Leclerc—who now approached. Those who knew her called her Paulette. She had married General Leclerc on the 18th Brumaire, the day that had given her brother Bonaparte’s career such a fortunate nudge forward.

Entering from the room where she had just dressed, with perfectly studied coquetry she was just beginning to pull on her gloves: a gesture that called attention to her lovely, plump white arms adorned with gold cameo bracelets. Her hair was done up in small bands of fine leather that looked like leopard skin, and attached to them were bunches of gold grapes; it faithfully copied the coif of a bacchante on a cameo that might have come from ancient Greece. Her dress was made of the finest Indian muslin, like woven air, as Juvenal said. Its hem was embroidered with a garland in gold leaf two or three inches wide. A tunic in pure Greek style hung down over her lovely waist and was attached at her shoulders by costly cameos. The very short sleeves, slightly pleated, ended in tiny cuffs, which were also held in place by cameos. Just below her breasts she wore a belt of burnished gold, its buckle a lovely engraved stone. The ensemble was so harmonious, and her beauty so delicious, that when she appeared, no other woman graced the room.

“Incessu patuit dea,” said Dupaty as she passed.

“Do you insult me in a language I do not understand, Citizen Poet?” asked Madame Leclerc with a smile.

“What?” answered Dupaty. “You are from Rome, madame, and you don’t understand Latin?”

“I’ve forgotten all my Latin.”

“That is one of Virgil’s hemistiches, Madame, when Venus appeared to Aeneas. Abbé Delille translated it like this: ‘She walks by, and her steps reveal a goddess.’”

“Give me your arm, flatterer, and dance the first quadrille with me. That will be your punishment.”

Dupaty didn’t need to be asked twice. He held out his arm, straightened his legs, and allowed himself to be led by Madame Leclerc into a boudoir, where she stopped on the pretext that it was cooler than the larger rooms. In reality, though, it was because the boudoir offered an immense sofa that enabled the divine coquette to display her couture and her beauty to best effect.

As she passed Madame de Contades, the most beautiful woman in the room only so long as Madame Leclerc had not been present, the grand coquette cast a defiant glance. And she had the satisfaction of seeing all her rival’s admirers abandon Madame de Contades in her armchair and gather now around the sofa.

Madame de Contades bit her lips until they bled. But in the quiver of revenge that every woman wears at her side, she found one of those poisoned arrows that can mortally wound, and she called to Monsieur de Noailles. “Charles,” she said, “lend me your arm so I can go see up close that marvel of beauty and clothing that has just attracted all of our butterflies.”

“Ah,” said the young man, “and you are going to make her realize that among these butterflies there is a bee. Sting, sting, Countess,” Monsieur de Noailles added. “These low-born Bonapartes have been nobles for too short a time. They need to be reminded that they are making a mistake in trying to mix with the old aristocracy. If you look carefully at that parvenu, you will find, I am sure, the stigmata of her plebian origins.”

With a laugh, the young man allowed himself to be led by Madame de Contades, who, nostrils flared, seemed to be blazing a trail. Once she’d reached the crowd of flatterers surrounding the lovely Madame Leclerc, she elbowed her way up to the front row.

Madame Leclerc afforded her rival a smile, for no doubt Madame de Contades felt obligated to pay her homage.

And indeed, Madame de Contades proceeded with a politesse that in no way disabused Madame Leclerc of her impression. Madame de Contades added her voice to the hymns of praise and admiration being offered up to the divinity on the sofa. Then, suddenly, as if she had just made a horrible discovery, she cried out, “Oh, my God! How terrible! Why does such a horrible deformity have to spoil one of nature’s masterpieces!” she exclaimed. “Must it be said that nothing in this world is perfect? My God, how sad!”

At this strange lamentation, everybody looked first at Madame de Contades, then at Madame Leclerc, then at Madame de Contades again. They were obviously waiting for her to explain her outburst, but Madame de Contades continued only to lament this sad case of human imperfection.

“Come now,” her escort finally said. “What do you see? Tell us what you see!”

“What do you mean? Tell you what I see? Can you not see those two enormous ears stuck on both sides of such a charming head? If I had ears like that, I would have them trimmed back a little. And since they have not been hemmed, that shouldn’t be difficult.”

Barely had Madame de Contades finished when all eyes turned toward Madame Leclerc’s head—not to admire it, but rather to remark her ears. For until then no one had even noticed them.

And indeed, Paulette, as her friends called her, did have unusual ears. The white cartilage looked signally like an oyster shell, and, as Madame de Contades had pointed out, it was cartilage that nature had neglected to hem.

Madame Leclerc did not even try to defend herself against such an impertinent attack. Instead, she availed herself of that resource any woman wronged might use: She uttered a cry and collapsed.

At the same moment, her erstwhile admirers heard a carriage rolling up to the Permon mansion, and a horse galloping, then a voice calling out “The First Consul!”—all of which distracted everyone’s attention from the bizarre scene that had just transpired.

Except that, while Madame Leclerc was rushing from the boudoir in tears and the First Consul was striding in through one of the ballroom doors, Madame de Contades, her attack triumphant but too brutal perhaps, was stealing out through another.

XII The Queen’s Minuet

MADAME DE PERMON WALKED up to the First Consul and bowed with great ceremony. Bonaparte took her hand and kissed it most gallantly.

“What’s this I hear, my dear friend?” he said. “Did you really refuse to open the ball before I arrived? And what if I had not been able to come before one in the morning—would all these lovely children have had to wait for me?”

Glancing around the room, he saw that some of the women from the Faubourg Saint-Germain had failed to rise when he came in. He frowned, but showed no other signs of displeasure.

“Come now, Madame de Permon,” he said. “Let the ball begin. Young people need to have fun, and dancing is their favorite pastime. They say that Loulou can dance like Mademoiselle Chameroi. Who told me that? It was Eugene, wasn’t it?”

Eugene’s ears turned red; he was the beautiful ballerina’s lover.

Bonaparte continued: “If you wish, Madame de Permon, we shall dance the monaco. That’s the only dance I know.”

“Surely you are joking,” Madame de Permon answered. “I have not danced in thirty years.”

“Come now, you can’t mean that,” said Bonaparte. “This evening you look like your daughter’s sister.”

Then, noticing Monsieur de Talleyrand, Bonaparte said, “Oh, it’s you, Talleyrand. I need to talk to you.” And with his Foreign Affairs Minister he went into the boudoir where Madame Leclerc had endured her embarrassment just moments before.

Immediately, the music began, the dancers chose partners, and the ball was under way.

Mademoiselle de Beauharnais, who was dancing with Duroc, led him over to Claire and the Comte de Sainte-Hermine, for everything her friend had told her about the young man had piqued her interest.

Monsieur de Sainte-Hermine was proving to be no less talented on the ballroom floor than he was in other areas. He had studied with the second Vestris, the son of France’s own god of dance, and he did his teacher great honor.

During the Consulate years, a young man of fashion considered it requisite to perfect the art of dancing. I can still remember having seen, when I was a child, in 1812 or 1813, the two Monbreton brothers—the very same who were dancing at Madame de Permon’s ball this evening a dozen years earlier—in Villers-Cotterêts, where a grand ball brought together the entire beautiful new aristocracy. The Montbretons came from their castle in Corcy, three leagues away, and guess how they came. In their cabriolets. Yes, but their domestics rode inside the cabriolet, while they themselves, wearing their fine pump dancing shoes, held on to straps in the back, on the springboard where normally their valets stood, so that on the road they could continue to practice their intricate steps. Arriving at the ballroom door just in time to join the first quadrille, they had their domestics brush the dust off their clothes and threw themselves into the lively reel.

However brilliantly the Montbretons may have danced at Madame de Permon’s, it was Sainte-Hermine who impressed Mademoiselle de Beauharnais, and Mademoiselle de Sourdis was proud to see that the count, who had never before deigned to dance, with skill and grace could hold his own with the best dancers at the ball. Although Mademoiselle de Beauharnais was reassured on that point, there was still another that worried the curious Hortense: Had the young man spoken to Claire? Had he told her the cause of his long sadness, of his past silence, of his present joy?

Hortense ran to her friend and, pulling her into a bay window, asked: “Well, what did he say?”

“Something very important concerning what I told you.”

“Can you tell me?” Spurred by curiosity, Mademoiselle was using the informal tu form with her friend Claire, though normally in conversation they used formal address.

Claire lowered her voice. “He said he wanted to tell me a family secret.”

“You?”

“Me alone. Consequently, he begged me to get my mother to agree that he might be able to speak to me for an hour, with my mother watching but far enough away that she’d not be able to hear what he’d say. His life’s happiness, he said, depended on it.”

“Will your mother permit it?”

“I hope so, for she loves me dearly. I have promised to ask my mother this evening and to give him my answer at the end of the ball.”

“And now,” said Mademoiselle de Beauharnais, “do you realize how handsome your Comte de Sainte-Hermine is, and that he dances as well as Gardel?”

The music, signaling the second quadrille, called the girls back to their places. The two young friends had been, as we have seen, quite satisfied with how well Monsieur de Sainte-Hermine had danced the quadrille. But then, it was only a quadrille. There were yet two tests to which every unproven dancer was put: the gavotte and the minuet.

The young count had promised the gavotte to Mademoiselle de Beauharnais. It’s a dance we know today only by tradition, and though we may think it quite ridiculous, it was de rigeur during the Directory, the Consulate, and even the Empire. Like a snake that keeps twisting even after it has been cut into pieces, the gavotte could never quite die. It was, in fact, more a theatrical performance than a ballroom dance, for it had very complicated figures that were quite difficult to execute. The gavotte required a great deal of space, and even a large ballroom could accommodate no more than four couples at the same time.

Among the four couples dancing the gavotte in Madame de Permon’s grand ballroom, the two dancers whom everyone loudly applauded were the Comte de Sainte-Hermine and Mademoiselle de Beauharnais. They were applauded so enthusiastically, in fact, that they drew Bonaparte both out of his conversation with Monsieur de Talleyrand and out of the boudoir to which they’d withdrawn. Bonaparte appeared in the doorway just as his stepdaughter and her partner were completing the final figures, so he was able to witness their triumph.