Полная версия:

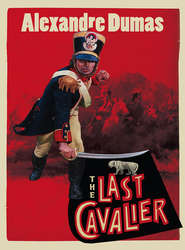

The Last Cavalier: Being the Adventures of Count Sainte-Hermine in the Age of Napoleon

Among the guests were the most elegant people in Paris. There were the government officials, that marvelous staff of generals, the oldest of whom was no more thirty-five: Murat, Marmont, Junot, Duroc, Lannes, Moncey, Davout—already heroes at an age when one is normally only a captain. There were poets: Lemercier, still proud of the recent success of his Agamemnon; Chénier, who had written Timoléon, then given up theater and thrown himself into politics; Chateaubriand, who had just discovered God at Niagara Falls and in the depths of America’s virgin forests. There were famous dancers without whom grand balls could not be held: Trénis, Laffitte, Dupaty, Garat, Vestris. And there were the new century’s splendid stars who had appeared in the East: Madame Récamier, Madame Méchin, Madame de Contades, Madame Regnault de Saint-Jean-d’Angély. Finally, there was the brilliant young crowd, made up of men like Caulaincourt, Narbonne, Longchamp, Matthieu de Montmorency, Eugène de Beauharnais, and Philippe de Ségur.

From the moment the word got out that the First Consul and Madame Bonaparte not only were attending the wedding celebration but also would be signing the marriage contract, all society sought an invitation. Guests filled the ground floor and the first story of Madame de Sourdis’s spacious hotel, and they spread out onto the terraces, there to seek relief from the hot, stuffy rooms in the cool evening air.

At quarter to eleven, a mounted escort was seen leaving the Tuileries gates, with each man carrying a torch. Once they had crossed the bridge, the First Consul’s carriage, rolling at a triple gallop, surrounded by torches, swept by in the thunder of hoofbeats and a whirlwind of sparks before it disappeared into the hotel courtyard.

In the midst of a crowd so dense that it seemed impossible for anyone to penetrate, a passage magically opened and, inside the ballroom, widened into a circle that allowed Madame de Sourdis and Claire to approach the First Consul and Josephine. Hector de Sainte-Hermine walked behind Claire and her mother, and though he paled visibly on seeing Bonaparte, he nonetheless stood nobly before him.

Madame Bonaparte embraced Mademoiselle de Sourdis and placed on her arm a pearl necklace worth fifty thousand francs. Bonaparte greeted the two women, then moved toward Hector. Not suspecting that Bonaparte indeed meant to address him, Hector began to step aside. But Bonaparte stopped to face him.

“Monsieur,” said Bonaparte, “if I had not been afraid you would refuse it, I would have brought a gift for you as well, an appointment to the consular guard. But I understand that some wounds need time to heal.”

“For such cures, General, no one has a more skillful hand than you. However.…” Hector sighed and raised his handkerchief to his eyes. “Excuse me, General,” said the young man, after a pause. “I would like to be more worthy of your kindness.”

“That is what comes from having too much heart, young man,” said Bonaparte. “It is always the heart that suffers.”

Turning again to Madame de Sourdis, the First Consul exchanged a few words with her, and complimented Claire. Then he noticed Vestris.

“Oh, there’s young Vestris,” he said. “He lately did me a kindness for which I shall be eternally grateful. He was coming back to perform at the Opera after a short illness, and the performance happened to fall on a day that I was having a reception at the Tuileries. He changed his performance date so as not to conflict with my reception.… Come, Monsieur Vestris, please demonstrate your inimitable courteousness by asking two of these ladies to dance a gavotte for us.”

“Citizen First Consul,” answered this son to the god of dance in an Italian accent that the family had never been able to eradicate, “we are pleased to have just the dance for you, a gavotte I composed for Mademoiselle de Coigny. Madame Récamier and Mademoiselle de Sourdis dance it like angels. All we need is a harp and a horn,” he said, rolling his “r”s, “if Mademoiselle de Sourdis is willing to play the tambourine as she dances. As for Madame Récamier, you know that she is unbeatable in the shawl dance.”

“Come, my ladies,” said the First Consul. “You surely cannot refuse the request that Monsieur Vestris has made and which I support with all my power.”

Mademoiselle de Sourdis would have been happy to escape the ovation given to her, but once her dancing master Vestris had chosen her, and after the First Consul had added his bidding, she did not wait to be asked again.

She was dressed perfectly for this dance. Her white dress, accented by her dark skin, had two clusters of grapes on the shoulders, while grape leaves in reddish autumn colors ran the length of her gown. She also wore grape leaves in her hair.

Madame Récamier was wearing her customary white dress and her red Indian cashmere shawl. The creator of the shawl dance, which had so successfully been taken from the ballroom to the theater, Madame Récamier performed her invention with no want of modesty yet without a hint of constraint as no theater bayadère or professional actress has demonstrated since. Beneath the undulations of the supple cashmere cloth, she was able to reveal her charms at the same time she was pretending to hide them.

The dance lasted nearly a quarter of an hour and ended in a crescendo of applause, to which the First Consul added his own. At his signal, the entire room exploded in bravos. Amidst the boisterous praise, Vestris seemed to be walking on air as he took full credit for all that poetry of form and movement, of expression and attitude.

Once the gavotte had finished, a servant in livery whispered a few words to the Comtesse de Sourdis, to which she responded, “Open the drawing room.”

Two doors slid open, and in the marvelously elegant drawing room, brightly lit, two men of the law were seated at a table lit by two candelabras, between which the marriage contract was awaiting the signatures with which it would soon be honored. The only people authorized to enter the drawing room were the twenty or so who would be signing the contract, which would first be read aloud for the benefit of the other wedding guests.

As the contract was being read, a second lackey in livery entered. As unobtrusively as he could, he slipped over to the Comte de Sainte-Hermine and in a whisper said, “Monsieur le Chevalier de Mahalin asks to speak to you at this very moment.”

“Have him wait,” said Sainte-Hermine, who was standing attendant in the small study at one side of the drawing room.

“Monsieur le Comte, he says that he must see you at this very instant. Even if you were to have the pen in your hand, he would request that you lay it down on the table and come to see him before you sign … oh, there he is at the door.”

With what looked like a gesture of despair, the count joined the Chevalier outside the drawing room. Few people noticed the discreet exit, and those who did were unaware of its unfortunate significance.

After the contract had been read, Bonaparte, always in a hurry to finish what was under way, as eager to leave the Tuileries when he was there as he was to return when he was out, picked up the pen that was lying on the table. Without wondering whether he should be the first to sign, he hastily placed his signature on the contract, and then, just as four years later he would take the crown from the pope’s hands and place it himself on Josephine’s head, he handed his wife the pen.

Josephine signed, then passed the pen to Mademoiselle de Sourdis, who instinctively looked around worriedly, but in vain, for the Comte de Sainte-Hermine. Filled with anxiety, she signed her name and tried to hide her concern. But it was the Comte’s turn next to sign.

A murmur disturbed the drawing room as heads turned in search of the bridegroom. Soon there was no choice but to call out for him. Only there was no answer.

For a long moment, in surprised silence, the guests looked at each other, all of them, wondering what could have happened to the count at the very moment his presence was indispensable and his absence a complete lapse of etiquette.

Finally someone mentioned that during the reading of the contract, a young well-dressed stranger had appeared in the dorway to the drawing room and had exchanged a few whispered words with the count before leading him off, more like his executioner than his friend.

Still, the count might not have left the house. Madame de Sourdis rang for a servant and ordered him to organize a search for the absent bridegroom. For several minutes, amidst the buzz of six hundred stunned wedding guess, servants could be heard calling out to each other from one floor to the next.

Then one of the servants thought to ask the coachmen out in the courtyard if they had seen two young men. Several of them had, as it happened. They’d noticed that one of the young men had been hatless in spite of the rain. They reported that the two men had rushed down the steps and leaped into a carriage, shouting, “To the stagecoach house!” and the carriage had galloped off. One of the coachmen was certain he had recognized the young man without a hat: It was the Comte de Sainte-Hermine.

The guests looked at each other in stupefaction. Then, out of the silence, they heard a voice shout: “The carriage and escort for the First Consul!” They all respectfully allowed Monsieur and Madame Bonaparte, along with Madame Louis Bonaparte, to pass. And as soon as they had left, pandemonium struck.

Everyone rushed from the elegant rooms of Madame de Sourdis’s grand house as if there were a fire.

Neither Madame de Sourdis nor Claire, however, had any inclination to stop them. Fifteen minutes later they found themselves alone.

Madame de Sourdis, with a painful cry, rushed to her daughter’s side. Claire was trembling, about to faint. “Oh, Mother, Mother!” she cried, bursting into sobs as she collapsed into the countess’s arms, “it is just what the prophetess predicted! My widowhood has begun.”

XXIII The Burning Brigades

WE SHOULD EXPLAIN why Mademoiselle de Sourdis’s fiancé disappeared so incomprehensibly just as the marriage contract was to be signed. For the guests, his disappearance was the cause for surprise; for the countess, it prompted all sorts of speculations, each new one more improbable than the last. For her daughter, it elicited incessant tears.

We have seen that Fouché summoned the Chevalier de Mahalin to his office the day before news of his dismissal was to be publicly announced. Hoping to get back his ministry, Fouché then planned with Mahalin the organization of burning brigades in the West.

The bands of incendiaries had soon begun to appear, and already they had left their mark. Scarcely two weeks after the Chevalier had left Paris, it was learned that two landowners had been burned, one in Buré and the other in Saulnaye. Again, terror was spreading throughout the Morbihan.

For five years civil war had raged in that unfortunate region, but even in the midst of its most horrible outrages against humanity, never had such banditry as this been practiced. To find robbery and torture of the kind that accompanied these burnings, one had to go back to the worst days of Louis XV and to the horrors of religious discrimination under Louis XIV.

Terror came in bands of ten, fifteen, or twenty men who seemed to rise out of the earth and move like shadows over the land, following ravines, leaping across stiles; and any peasants who had ventured out late in the night had to hide behind trees or throw themselves facedown behind hedges, or else fall prey to the brigands. Then, suddenly, through a half-open window or a poorly closed door, they would burst into some farmhouse or chateau and, taking the servants by surprise, bind them up. Next, they would light a fire in the middle of the kitchen; they’d drag the master or mistress of the house over to it and lay their victim down on the floor with his feet to the flames until pain forced him to reveal where his money was hidden. Sometimes they would then free their prisoner. Other times, once they’d got the money, if they feared they might be identified, they would stab, hang, or bludgeon to death the unfortunate they had robbed.

After the third or fourth episode of that kind, after the authorities had indeed confirmed the fires and murders, the rumor began to spread, at first secretly, then quite openly, that Cadoudal himself strode at the head of those gangs. The brigands and their leader always wore masks, but some who had seen the largest of the bands stalk through the night were sure they had recognized the leader as George Cadoudal—by his size, by his bearing, and especially by his large round head.

This was difficult to believe. How could George Cadoudal, who acted so honorably in all things, have suddenly become the contemptible chief of a shameless, pitiless burning brigade?

Yet the rumor kept growing. More and more people claimed they had recognized George, and soon Le Journal de Paris officially announced that Cadoudal, in spite of his promise not to be the first to open hostilities—Cadoudal who had disbanded his Royalist forces—had now scraped together fifty or so bandits with whom he was terrorizing the countryside.

In London, Cadoudal himself might not have happened upon the article in Le Journal de Paris, but a friend showed it to him. He took the official announcement as an accusation against him, and he saw the accusation as a flagrant attack on his honor and loyalty.

“Very well,” he said, “by attacking me the French authorities have broken the pact we swore between us. They were unable to kill me with gun and sword, so now they are trying to kill me with calumny. They want war, and war they shall have.”

That very evening George embarked on a fishing boat. Five days later it landed him on the French coast, between Port-Louis and the Quiberon peninsula.

At the same time, two other men, Saint-Régeant and Limoëlan, were also leaving London to go to Paris. As they would be traveling through Normandy, they’d enter the country by the cliffs near Biville. They had spent one hour with George the day they left, to receive their instructions. Limoëlan had considerable experience in the intrigues of civil war, and Saint-Régeant was a former naval officer, skilled and resourceful, a sea pirate who had become a land pirate.

It was on such lost men—rather than the likes of Guillemot and Sol de Grisolles—that Cadoudal was now forced to depend to execute his plans. In any case, it was clear that his goals and theirs were one and the same.

This is what transpired.

Near the end of April 1804, at about five in the afternoon, a man wrapped in a greatcoat galloped into the courtyard of the Plescop farm owned by Jacques Doley. A wealthy farmer, Doley lived there with his sixty-year-old mother-in-law and his thirty-year-old wife, with whom he had two children: one a boy of ten, the other a girl of seven. He had ten servants, both men and women, who helped him run the farm.

The man in the greatcoat asked to speak to the master of the house and closed himself up in the milk room with him for a half hour, but then failed to reappear. Jacques Doley came back out of the room alone.

During dinner, everyone noticed how quiet and preoccupied Jacques seemed to be. Several times his wife spoke to him, but he did not answer. After the meal, when the children tried to play with him as they usually did, he gently pushed them away.

In Brittany, as you know, the servants eat at the master’s table. On that day, they too noticed how sad Doley was, and found it surprising because by nature he was quite jovial. Just a few days before, the Château de Buré had been burned, and that is what the servants were talking quietly about during the meal. As Doley listened to them, he raised his head a few times as if he were about to ask something, but each time without interrupting them. From time to time, though, the old mother made the sign of the cross, and near the end of the servants’ tale, Madame Doley, no longer able to control her fear, moved closer to her husband.

By eight in the evening, it was completely dark. That was when all of the servants usually retired, some to the barn, some to the stables, but Doley seemed to be trying to delay them, as he gave them a series of orders that kept them from leaving. Also, now and then he would glance at the two or three double-barreled shotguns hanging on nails above the fireplace, like a man who would rather have them in hand.

Soon, however, each servant had left in turn, and the old woman went to put the children in their cribs, which stood between their parents’ bed and the outside wall. She returned from the bedroom to kiss her daughter and son-in-law good-night, then went to her own bed in a little cabinet attached to the kitchen.

Doley and his wife retired to the bedroom, which was separated from the kitchen by a glass door. Its two windows, protected by tightly closed oak shutters, opened out onto the garden. Near the top of the shutters, two small diamond-shaped openings admitted daylight even when the shutters were closed.

Although it was the time that Madame Doley, like all farm people, normally got undressed and went to bed, that evening, some vague worry troubled her out of her routine. She did finally get into her nightclothes, but before she’d actually get into bed she insisted that her husband check all the doors to be sure they were securely locked.

The farmer agreed, shrugging his shoulders like a man who thinks it is an unnecessary precaution. The first door he checked was the one that led from the kitchen to the milk room, but since it had only a few openings for light and no outside entrance, she did not disagree when her husband said, “To get in there, anyone would have to come in through the kitchen, and we have been in the kitchen all afternoon.”

He checked the courtyard gate; it was firmly locked with an iron bar and two bolts. The window too was secure. The door of the bake house had only one lock, but it was an oak door and a prison lock. Finally, there was the garden door, but to get to it, you would have to scale a ten-foot-high wall or break down the courtyard door, itself impregnable.

Somewhat reassured, Madame Doley went back into the bedroom but she still couldn’t keep from trembling. Doley sat down at his desk and pretended to be looking over his papers. Yet, whatever power he had over himself, he was unable to hide his worry, and the slightest sound would give him a start.

If he had begun to worry because of what he had learned during the day, he indeed had valid reasons. Roughly one hour from Plescop, a band of about twenty men was leaving the woods near Meucon and starting across open fields. Four were on horseback, riding in front like a vanguard and wearing uniforms of the Gendarmerie Nationale. The fifteen or sixteen others following on foot were not in uniform, and they were armed with guns and pitchforks. They were trying their best not to be seen. They stuck to the hedgerow, walked along ravines, crawled up hillsides, and got closer and closer to Plescop. Soon they were only a hundred paces away. They stopped to hold council.

One of the men moved out from the band and circled his way around to the farm. The others waited. They could hear a dog barking, but they could not tell if it came from inside the farm or a neighboring house.

The scout came back. He had walked around the farmhouse but had found no way in. Again they held council. They decided that they would have to force their way in.

They advanced. They stopped only when they reached the wall. That’s when they realized that the barking dog was on the wall’s other side, in the garden.

They started toward the gate. On its side, so did the dog, barking even more ferociously. They had been discovered; their element of surprise was lost.

The four horsemen in gendarme uniforms went to the gate, while the bandits on foot pressed themselves back against the wall. Now sticking its nose under the gate, the dog was barking desperately.

A voice called out, a man’s voice: “What’s the matter, Blaireau? What’s wrong, old boy?”

The dog turned toward the voice and howled plaintively.

Another voice called out from a little farther away, a woman’s voice: “You are not going to open the gate, I hope!”

“And why not?” the man’s voice asked.

“Because it could be brigands, you imbecile!”

Both voices went quiet.

“In the name of the law,” someone shouted on the other side of the gate: “Open up!”

“Who are you, to speak in the name of the law?” the man’s voice asked.

“The gendarmerie from Vannes. We have come to search Monsieur Doley’s farm. He has been accused of giving refuge to Chouans.”

“Don’t listen to them, Jean,” said the woman. “It’s a trick. They’re just saying that to get you to open the gate.”

Jean, the gardener, was of the same opinion as his wife, for he had quietly carried a ladder over to the courtyard wall and climbed up to its top. Looking over, he could see not only the four men on horseback but also roughly fifteen men crowded up against the wall.

Meanwhile, the men dressed like gendarmes kept shouting: “Open up in the name of the law.” And three of them began pounding at the gate with the butt end of their guns while threatening to break it down if it was not opened.

The noise of their pounding reached all the way to the farmer’s bedroom. Madame Doley’s terror increased. Shaken by his wife’s alarm, Doley was still trying to bring himself to leave the house and open the gate when the stranger emerged from the milk room, grabbed the farmer’s arm, and said: “What are you waiting for? Did I not tell you I’d take care of everything?”

“Who are you speaking to?” cried Madame Doley.

“Nobody at all,” Doley answered, hurrying out from the kitchen.

As soon as he opened the door, he could hear the gardener and his wife talking to the bandits, and although he was not duped by the bandits’ trickery, he called out: “Well, Jean, why are you so stubbornly refusing to open up to the police? You know that it is wrong to try to resist them. Please excuse this man, gentlemen,” Doley continued, walking toward the gate. “He is not acting on my orders.”

Jean had recognized Monsieur Doley. He ran up to him. “Oh, Master Doley,” he said. “I’m not mistaken. You are. They aren’t real gendarmes. In the name of heaven, don’t open up.”

“I know what’s happening and what I have to do,” said Jacques Doley. “Go back to your rooms and lock yourself in. Or if you are afraid, take your wife and go hide in the willows. They will never look there for you.”

“But you! What about you?”

“There’s someone here who has promised to defend me.”

“Come on, are you going to open up?” roared the leader of the supposed gendarmes, “or must I break the gate down?” And once again they pounded three or four times on the gate with the butts of their guns, which threatened to knock the gate off its hinges.

“I said I was going to open up,” shouted Jacques Doley.

And he did.

The brigands swarmed over Jacques Doley, grabbing him by the collar. “Gentlemen,” he said. “Don’t forget that I willingly opened the gate for you. You realize that I have ten or eleven men working here. I could have given them weapons. We could have defended ourselves from behind these walls and done severe damage before surrendering.”

“But you didn’t. Because you thought you were dealing with gendarmes and not with us.”

Jacques showed them the ladder placed against the wall. “Yes, except that Jean saw you all from up on that ladder.”

“Since you did open the gate, what do you expect?”

“That you will be less demanding. If I had not opened the gate, you might have burned my farm in a moment of rage!”

“And who’s to say that we won’t burn your farm in a moment of joy?”

“That would be unnecessary cruelty. You want my money, fine. But you do not wish my ruin.”