Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 1, 1833-1856

I have two floors here —entresol and first – in a doll's house, but really pretty within, and the view without astounding, as you will say when you come. The house is on the Exposition side, about half a quarter of a mile above Franconi's, of course on the other side of the way, and close to the Jardin d'Hîver. Each room has but one window in it, but we have no fewer than six rooms (besides the back ones) looking on the Champs Elysées, with the wonderful life perpetually flowing up and down. We have no spare-room, but excellent stowage for the whole family, including a capital dressing-room for me, and a really slap-up kitchen near the stairs. Damage for the whole, seven hundred francs a month.

But, sir – but – when Georgina, the servants, and I were here for the first night (Catherine and the rest being at Boulogne), I heard Georgy restless – turned out – asked: "What's the matter?" "Oh, it's dreadfully dirty. I can't sleep for the smell of my room." Imagine all my stage-managerial energies multiplied at daybreak by a thousand. Imagine the porter, the porter's wife, the porter's wife's sister, a feeble upholsterer of enormous age from round the corner, and all his workmen (four boys), summoned. Imagine the partners in the proprietorship of the apartment, and martial little man with François-Prussian beard, also summoned. Imagine your inimitable chief briefly explaining that dirt is not in his way, and that he is driven to madness, and that he devotes himself to no coat and a dirty face, until the apartment is thoroughly purified. Imagine co-proprietors at first astounded, then urging that "it's not the custom," then wavering, then affected, then confiding their utmost private sorrows to the Inimitable, offering new carpets (accepted), embraces (not accepted), and really responding like French bricks. Sallow, unbrushed, unshorn, awful, stalks the Inimitable through the apartment until last night. Then all the improvements were concluded, and I do really believe the place to be now worth eight or nine hundred francs per month. You must picture it as the smallest place you ever saw, but as exquisitely cheerful and vivacious, clean as anything human can be, and with a moving panorama always outside, which is Paris in itself.

You mention a letter from Miss Coutts as to Mrs. Brown's illness, which you say is "enclosed to Mrs. Charles Dickens."

It is not enclosed, and I am mad to know where she writes from that I may write to her. Pray set this right, for her uneasiness will be greatly intensified if she have no word from me.

I thought we were to give £1,700 for the house at Gad's Hill. Are we bound to £1,800? Considering the improvements to be made, it is a little too much, isn't it? I have a strong impression that at the utmost we were only to divide the difference, and not to pass £1,750. You will set me right if I am wrong. But I don't think I am.

I write very hastily, with the piano playing and Alfred looking for this.

Ever, my dear Wills, faithfully.Mr. W. H. Wills49, Avenue des Champs Elysées,Wednesday, Oct. 24th, 1855.My dear Wills,

In the Gad's Hill matter, I too would like to try the effect of "not budging." So do not go beyond the £1,700. Considering what I should have to expend on the one hand, and the low price of stock on the other, I do not feel disposed to go beyond that mark. They won't let a purchaser escape for the sake of the £100, I think. And Austin was strongly of opinion, when I saw him last, that £1,700 was enough.

You cannot think how pleasant it is to me to find myself generally known and liked here. If I go into a shop to buy anything, and give my card, the officiating priest or priestess brightens up, and says: "Ah! c'est l'écrivain célèbre! Monsieur porte un nom très-distingué. Mais! je suis honoré et intéressé de voir Monsieur Dick-in. Je lis un des livres de monsieur tous les jours" (in the Moniteur). And a man who brought some little vases home last night, said: "On connaît bien en France que Monsieur Dick-in prend sa position sur la dignité de la littérature. Ah! c'est grande chose! Et ses caractères" (this was to Georgina, while he unpacked) "sont si spirituellement tournées! Cette Madame Tojare" (Todgers), "ah! qu'elle est drôle et précisément comme une dame que je connais à Calais."

You cannot have any doubt about this place, if you will only recollect it is the great main road from the Place de la Concorde to the Barrière de l'Étoile.

Ever faithfully.Monsieur RegnierWednesday, November 21st, 1855.My dear Regnier,

In thanking you for the box you kindly sent me the day before yesterday, let me thank you a thousand times for the delight we derived from the representation of your beautiful and admirable piece. I have hardly ever been so affected and interested in any theatre. Its construction is in the highest degree excellent, the interest absorbing, and the whole conducted by a masterly hand to a touching and natural conclusion.

Through the whole story from beginning to end, I recognise the true spirit and feeling of an artist, and I most heartily offer you and your fellow-labourer my felicitations on the success you have achieved. That it will prove a very great and a lasting one, I cannot for a moment doubt.

O my friend! If I could see an English actress with but one hundredth part of the nature and art of Madame Plessy, I should believe our English theatre to be in a fair way towards its regeneration. But I have no hope of ever beholding such a phenomenon. I may as well expect ever to see upon an English stage an accomplished artist, able to write and to embody what he writes, like you.

Faithfully yours ever.Madame Viardot49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, Monday, Dec. 3rd, 1855.Dear Madame Viardot,

Mrs. Dickens tells me that you have only borrowed the first number of "Little Dorrit," and are going to send it back. Pray do nothing of the sort, and allow me to have the great pleasure of sending you the succeeding numbers as they reach me. I have had such delight in your great genius, and have so high an interest in it and admiration of it, that I am proud of the honour of giving you a moment's intellectual pleasure.

Believe me, very faithfully yours.The Hon. Mrs. WatsonTavistock House, Sunday, Dec. 23rd, 1855.My dear Mrs. Watson,

I have a moment in which to redeem my promise, of putting you in possession of my Little Friend No. 2, before the general public. It is, of course, at the disposal of your circle, but until the month is out, is understood to be a prisoner in the castle.

If I had time to write anything, I should still quite vainly try to tell you what interest and happiness I had in once more seeing you among your dear children. Let me congratulate you on your Eton boys. They are so handsome, frank, and genuinely modest, that they charmed me. A kiss to the little fair-haired darling and the rest; the love of my heart to every stone in the old house.

Enormous effect at Sheffield. But really not a better audience perceptively than at Peterboro', for that could hardly be, but they were more enthusiastically demonstrative, and they took the line, "and to Tiny Tim who did not die," with a most prodigious shout and roll of thunder.

Ever, my dear Friend, most faithfully yours.1856

NARRATIVECharles Dickens having taken an appartement in Paris for the winter months, 49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, was there with his family until the middle of May. He much enjoyed this winter sojourn, meeting many old friends, making new friends, and interchanging hospitalities with the French artistic world. He had also many friends from England to visit him. Mr. Wilkie Collins had an appartement de garçon hard by, and the two companions were constantly together. The Rev. James White and his family also spent their winter at Paris, having taken an appartement at 49, Avenue des Champs Elysées, and the girls of the two families had the same masters, and took their lessons together. After the Whites' departure, Mr. Macready paid Charles Dickens a visit, occupying the vacant appartement.

During this winter Charles Dickens was, however, constantly backwards and forwards between Paris and London on "Household Words" business, and was also at work on his "Little Dorrit."

While in Paris he sat for his portrait to the great Ary Scheffer. It was exhibited at the Royal Academy Exhibition of this year, and is now in the National Portrait Gallery.

The summer was again spent at Boulogne, and once more at the Villa des Moulineaux, where he received constant visits from English friends, Mr. Wilkie Collins taking up his quarters for many weeks at a little cottage in the garden; and there the idea of another play, to be acted at Tavistock House, was first started. Many of our letters for this year have reference to this play, and will show the interest which Charles Dickens took in it, and the immense amount of care and pains given by him to the careful carrying out of this favourite amusement.

The Christmas number of "Household Words," written by Charles Dickens and Mr. Collins, called "The Wreck of the Golden Mary," was planned by the two friends during this summer holiday.

It was in this year that one of the great wishes of his life was to be realised, the much-coveted house – Gad's Hill Place – having been purchased by him, and the cheque written on the 14th of March – on a "Friday," as he writes to his sister-in-law, in the letter of this date. He frequently remarked that all the important, and so far fortunate, events of his life had happened to him on a Friday. So that, contrary to the usual superstition, that day had come to be looked upon by his family as his "lucky" day.

The allusion to the "plainness" of Miss Boyle's handwriting is good-humouredly ironical; that lady's writing being by no means famous for its legibility.

The "Anne" mentioned in the letter to his sister-in-law, which follows the one to Miss Boyle, was the faithful servant who had lived with the family so long; and who, having left to be married the previous year, had found it a very difficult matter to recover from her sorrow at this parting. And the "godfather's present" was for a son of Mr. Edmund Yates.

"The Humble Petition" was written to Mr. Wilkie Collins during that gentleman's visit to Paris.

The explanation of the remark to Mr. Wills (6th April), that he had paid the money to Mr. Poole, is that Charles Dickens was the trustee through whom the dramatist received his pension.

The letter to the Duke of Devonshire has reference to the peace illuminations after the Crimean war.

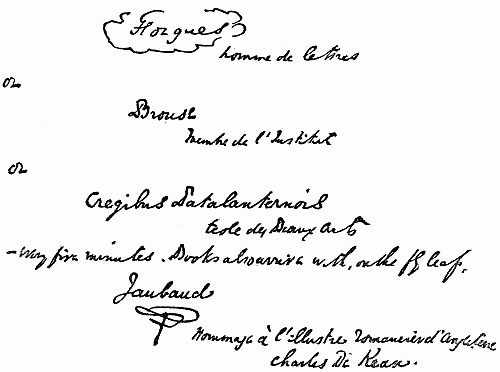

The M. Forgues for whom, at Mr. Collins's request, he writes a short biography of himself, was the editor of the Revue des Deux Mondes.

The speech at the London Tavern was on behalf of the Artists' Benevolent Fund.

Miss Kate Macready had sent some clever poems to "Household Words," with which Charles Dickens had been much pleased. He makes allusion to these, in our two remaining letters to Mr. Macready.

"I did write it for you" (letter to Mrs. Watson, 17th October), refers to that part of "Little Dorrit" which treats of the visit of the Dorrit family to the Great St. Bernard. An expedition which it will be remembered he made himself, in company with Mr. and Mrs. Watson and other friends.

The letter to Mrs. Horne refers to a joke about the name of a friend of this lady's, who had once been brought by her to Tavistock House. The letter to Mr. Mitton concerns the lighting of the little theatre at Tavistock House.

Our last letter is in answer to one from Mr. Kent, asking him to sit to Mr. John Watkins for his photograph. We should add, however, that he did subsequently give this gentleman some sittings.

Mr. W. H. Wills49, Champs Elysées, Sunday, Jan. 6th, 1856.My dear Wills,

I should like Morley to do a Strike article, and to work into it the greater part of what is here. But I cannot represent myself as holding the opinion that all strikes among this unhappy class of society, who find it so difficult to get a peaceful hearing, are always necessarily wrong, because I don't think so. To open a discussion of the question by saying that the men are "of course entirely and painfully in the wrong," surely would be monstrous in any one. Show them to be in the wrong here, but in the name of the eternal heavens show why, upon the merits of this question. Nor can I possibly adopt the representation that these men are wrong because by throwing themselves out of work they throw other people, possibly without their consent. If such a principle had anything in it, there could have been no civil war, no raising by Hampden of a troop of horse, to the detriment of Buckinghamshire agriculture, no self-sacrifice in the political world. And O, good God, when – treats of the suffering of wife and children, can he suppose that these mistaken men don't feel it in the depths of their hearts, and don't honestly and honourably, most devoutly and faithfully believe that for those very children, when they shall have children, they are bearing all these miseries now!

I hear from Mrs. Fillonneau that her husband was obliged to leave town suddenly before he could get your parcel, consequently he has not brought it; and White's sovereigns – unless you have got them back again – are either lying out of circulation somewhere, or are being spent by somebody else. I will write again on Tuesday. My article is to begin the enclosed.

Ever faithfully.Mr. Mark Lemon49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Monday, Jan. 7th, 1856.My dear Mark,

I want to know how "Jack and the Beanstalk" goes. I have a notion from a notice – a favourable notice, however – which I saw in Galignani, that Webster has let down the comic business.

In a piece at the Ambigu, called the "Rentrée à Paris," a mere scene in honour of the return of the troops from the Crimea the other day, there is a novelty which I think it worth letting you know of, as it is easily available, either for a serious or a comic interest – the introduction of a supposed electric telegraph. The scene is the railway terminus at Paris, with the electric telegraph office on the prompt side, and the clerks with their backs to the audience– much more real than if they were, as they infallibly would be, staring about the house – working the needles; and the little bell perpetually ringing. There are assembled to greet the soldiers, all the easily and naturally imagined elements of interest – old veteran fathers, young children, agonised mothers, sisters and brothers, girl lovers – each impatient to know of his or her own object of solicitude. Enter to these a certain marquis, full of sympathy for all, who says: "My friends, I am one of you. My brother has no commission yet. He is a common soldier. I wait for him as well as all brothers and sisters here wait for their brothers. Tell me whom you are expecting." Then they all tell him. Then he goes into the telegraph-office, and sends a message down the line to know how long the troops will be. Bell rings. Answer handed out on slip of paper. "Delay on the line. Troops will not arrive for a quarter of an hour." General disappointment. "But we have this brave electric telegraph, my friends," says the marquis. "Give me your little messages, and I'll send them off." General rush round the marquis. Exclamations: "How's Henri?" "My love to Georges;" "Has Guillaume forgotten Elise?" "Is my son wounded?" "Is my brother promoted?" etc. etc. Marquis composes tumult. Sends message – such a regiment, such a company – "Elise's love to Georges." Little bell rings, slip of paper handed out – "Georges in ten minutes will embrace his Elise. Sends her a thousand kisses." Marquis sends message – such a regiment, such a company – "Is my son wounded?" Little bell rings. Slip of paper handed out – "No. He has not yet upon him those marks of bravery in the glorious service of his country which his dear old father bears" (father being lamed and invalided). Last of all, the widowed mother. Marquis sends message – such a regiment, such a company – "Is my only son safe?" Little bell rings. Slip of paper handed out – "He was first upon the heights of Alma." General cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. "He was made a sergeant at Inkermann." Another cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. "He was made colour-sergeant at Sebastopol." Another cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. "He was the first man who leaped with the French banner on the Malakhoff tower." Tremendous cheer. Bell rings again, another slip of paper handed out. "But he was struck down there by a musket-ball, and – Troops have proceeded. Will arrive in half a minute after this." Mother abandons all hope; general commiseration; troops rush in, down a platform; son only wounded, and embraces her.

As I have said, and as you will see, this is available for any purpose. But done with equal distinction and rapidity, it is a tremendous effect, and got by the simplest means in the world. There is nothing in the piece, but it was impossible not to be moved and excited by the telegraph part of it.

I hope you have seen something of Stanny, and have been to pantomimes with him, and have drunk to the absent Dick. I miss you, my dear old boy, at the play, woefully, and miss the walk home, and the partings at the corner of Tavistock Square. And when I go by myself, I come home stewing "Little Dorrit" in my head; and the best part of my play is (or ought to be) in Gordon Street.

I have written to Beaucourt about taking that breezy house – a little improved – for the summer, and I hope you and yours will come there often and stay there long. My present idea, if nothing should arise to unroot me sooner, is to stay here until the middle of May, then plant the family at Boulogne, and come with Catherine and Georgy home for two or three weeks. When I shall next run across I don't know, but I suppose next month.

We are up to our knees in mud here. Literally in vehement despair, I walked down the avenue outside the Barrière de l'Étoile here yesterday, and went straight on among the trees. I came back with top-boots of mud on. Nothing will cleanse the streets. Numbers of men and women are for ever scooping and sweeping in them, and they are always one lake of yellow mud. All my trousers go to the tailor's every day, and are ravelled out at the heels every night. Washing is awful.

Tell Mrs. Lemon, with my love, that I have bought her some Eau d'Or, in grateful remembrance of her knowing what it is, and crushing the tyrant of her existence by resolutely refusing to be put down when that monster would have silenced her. You may imagine the loves and messages that are now being poured in upon me by all of them, so I will give none of them; though I am pretending to be very scrupulous about it, and am looking (I have no doubt) as if I were writing them down with the greatest care.

Ever affectionately.Mr. W. Wilkie Collins49, Champs Elysées, Saturday, Jan. 19th, 1856.My dear Collins,

I had no idea you were so far on with your book, and heartily congratulate you on being within sight of land.

It is excessively pleasant to me to get your letter, as it opens a perspective of theatrical and other lounging evenings, and also of articles in "Household Words." It will not be the first time that we shall have got on well in Paris, and I hope it will not be by many a time the last.

I purpose coming over, early in February (as soon, in fact, as I shall have knocked out No. 5 of "Little D."), and therefore we can return in a jovial manner together. As soon as I know my day of coming over, I will write to you again, and (as the merchants – say Charley – would add) "communicate same" to you.

The lodging, en garçon, shall be duly looked up, and I shall of course make a point of finding it close here. There will be no difficulty in that. I will have concluded the treaty before starting for London, and will take it by the month, both because that is the cheapest way, and because desirable places don't let for shorter terms.

I have been sitting to Scheffer to-day – conceive this, if you please, with No. 5 upon my soul – four hours!! I am so addleheaded and bored, that if you were here, I should propose an instantaneous rush to the Trois Frères. Under existing circumstances I have no consolation.

I think the portrait23 is the most astounding thing ever beheld upon this globe. It has been shrieked over by the united family as "Oh! the very image!" I went down to the entresol the moment I opened it, and submitted it to the Plorn – then engaged, with a half-franc musket, in capturing a Malakhoff of chairs. He looked at it very hard, and gave it as his opinion that it was Misser Hegg. We suppose him to have confounded the Colonel with Jollins. I met Madame Georges Sand the other day at a dinner got up by Madame Viardot for that great purpose. The human mind cannot conceive any one more astonishingly opposed to all my preconceptions. If I had been shown her in a state of repose, and asked what I thought her to be, I should have said: "The Queen's monthly nurse." Au reste, she has nothing of the bas bleu about her, and is very quiet and agreeable.

The way in which mysterious Frenchmen call and want to embrace me, suggests to any one who knows me intimately, such infamous lurking, slinking, getting behind doors, evading, lying – so much mean resort to craven flights, dastard subterfuges, and miserable poltroonery – on my part, that I merely suggest the arrival of cards like this:

– and I then write letters of terrific empressement, with assurances of all sorts of profound considerations, and never by any chance become visible to the naked eye.

At the Porte St. Martin they are doing the "Orestes," put into French verse by Alexandre Dumas. Really one of the absurdest things I ever saw. The scene of the tomb, with all manner of classical females, in black, grouping themselves on the lid, and on the steps, and on each other, and in every conceivable aspect of obtrusive impossibility, is just like the window of one of those artists in hair, who address the friends of deceased persons. To-morrow week a fête is coming off at the Jardin d'Hîver, next door but one here, which I must certainly go to. The fête of the company of the Folies Nouvelles! The ladies of the company are to keep stalls, and are to sell to Messieurs the Amateurs orange-water and lemonade. Paul le Grand is to promenade among the company, dressed as Pierrot. Kalm, the big-faced comic singer, is to do the like, dressed as a Russian Cossack. The entertainments are to conclude with "La Polka des Bêtes féroces, par la Troupe entière des Folies Nouvelles." I wish, without invasion of the rights of British subjects, or risk of war, – could be seized by French troops, brought over, and made to assist.

The appartement has not grown any bigger since you last had the joy of beholding me, and upon my honour and word I live in terror of asking – to dinner, lest she should not be able to get in at the dining-room door. I think (am not sure) the dining-room would hold her, if she could be once passed in, but I don't see my way to that. Nevertheless, we manage our own family dinners very snugly there, and have good ones, as I think you will say, every day at half-past five.

I have a notion that we may knock out a series of descriptions for H. W. without much trouble. It is very difficult to get into the Catacombs, but my name is so well known here that I think I may succeed. I find that the guillotine can be got set up in private, like Punch's show. What do you think of that for an article? I find myself underlining words constantly. It is not my nature. It is mere imbecility after the four hours' sitting.

All unite in kindest remembrances to you, your mother and brother.

Ever cordially.Miss Mary Boyle49, Champs Elysées, Paris, Jan. 28th, 1856.My dear Mary,

I am afraid you will think me an abandoned ruffian for not having acknowledged your more than handsome warm-hearted letter before now. But, as usual, I have been so occupied, and so glad to get up from my desk and wallow in the mud (at present about six feet deep here), that pleasure correspondence is just the last thing in the world I have had leisure to take to. Business correspondence with all sorts and conditions of men and women, O my Mary! is one of the dragons I am perpetually fighting; and the more I throw it, the more it stands upon its hind legs, rampant, and throws me.