Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

The Letters of Charles Dickens. Vol. 1, 1833-1856

The sad affair of the Preston strike remains unsettled; and I hear, on strong authority, that if that were settled, the Manchester people are prepared to strike next. Provisions very dear, but the people very temperate and quiet in general. So ends this jumble, which looks like the index to a chapter in a book, I find, when I read it over.

Ever, my dear Cerjat, heartily your Friend.Mr. Arthur RylandTavistock House, January 18th, 1854.My dear Sir,

I am quite delighted to find that you are so well satisfied, and that the enterprise has such a light upon it. I think I never was better pleased in my life than I was with my Birmingham friends.

That principle of fair representation of all orders carefully carried out, I believe, will do more good than any of us can yet foresee. Does it not seem a strange thing to consider that I have never yet seen with these eyes of mine, a mechanic in any recognised position on the platform of a Mechanics' Institution?

Mr. Wills may be expected to sink, shortly, under the ravages of letters from all parts of England, Ireland, and Scotland, proposing readings. He keeps up his spirits, but I don't see how they are to carry him through.

Mrs. Dickens and Miss Hogarth beg their kindest regards; and I am, my dear sir, with much regard, too,

Very faithfully yours.Mr. Charles KnightTavistock House, January 30th, 1854.My dear Knight,

Indeed there is no fear of my thinking you the owner of a cold heart. I am more than three parts disposed, however, to be ferocious with you for ever writing down such a preposterous truism.

My satire is against those who see figures and averages, and nothing else – the representatives of the wickedest and most enormous vice of this time – the men who, through long years to come, will do more to damage the real useful truths of political economy than I could do (if I tried) in my whole life; the addled heads who would take the average of cold in the Crimea during twelve months as a reason for clothing a soldier in nankeens on a night when he would be frozen to death in fur, and who would comfort the labourer in travelling twelve miles a day to and from his work, by telling him that the average distance of one inhabited place from another in the whole area of England, is not more than four miles. Bah! What have you to do with these?

I shall put the book upon a private shelf (after reading it) by "Once upon a Time." I should have buried my pipe of peace and sent you this blast of my war-horn three or four days ago, but that I have been reading to a little audience of three thousand five hundred at Bradford.

Ever affectionately yours.Rev. James WhiteTavistock House, Tuesday, March 7th, 1854.My dear White,

I am tardy in answering your letter; but "Hard Times," and an immense amount of enforced correspondence, are my excuse. To you a sufficient one, I know.

As I should judge from outward and visible appearances, I have exactly as much chance of seeing the Russian fleet reviewed by the Czar as I have of seeing the English fleet reviewed by the Queen.

"Club Law" made me laugh very much when I went over it in the proof yesterday. It is most capitally done, and not (as I feared it might be) too directly. It is in the next number but one.

Mrs. – has gone stark mad – and stark naked – on the spirit-rapping imposition. She was found t'other day in the street, clothed only in her chastity, a pocket-handkerchief and a visiting card. She had been informed, it appeared, by the spirits, that if she went out in that trim she would be invisible. She is now in a madhouse, and, I fear, hopelessly insane. One of the curious manifestations of her disorder is that she can bear nothing black. There is a terrific business to be done, even when they are obliged to put coals on her fire.

– has a thing called a Psycho-grapher, which writes at the dictation of spirits. It delivered itself, a few nights ago, of this extraordinarily lucid message:

x. y. z!upon which it was gravely explained by the true believers that "the spirits were out of temper about something." Said – had a great party on Sunday, when it was rumoured "a count was going to raise the dead." I stayed till the ghostly hour, but the rumour was unfounded, for neither count nor plebeian came up to the spiritual scratch. It is really inexplicable to me that a man of his calibre can be run away with by such small deer.

À propos of spiritual messages comes in Georgina, and, hearing that I am writing to you, delivers the following enigma to be conveyed to Mrs. White:

"Wyon of the Mint lives at the Mint."Feeling my brain going after this, I only trust it with loves from all to all.

Ever faithfully.Mr. Charles KnightTavistock House, March 17th, 1854.My dear Knight,

I have read the article with much interest. It is most conscientiously done, and presents a great mass of curious information condensed into a surprisingly small space.

I have made a slight note or two here and there, with a soft pencil, so that a touch of indiarubber will make all blank again.

And I earnestly entreat your attention to the point (I have been working upon it, weeks past, in "Hard Times") which I have jocosely suggested on the last page but one. The English are, so far as I know, the hardest-worked people on whom the sun shines. Be content if, in their wretched intervals of pleasure, they read for amusement and do no worse. They are born at the oar, and they live and die at it. Good God, what would we have of them!

Affectionately yours always.Mr. W. H. WillsOffice of "Household Words,"No. 16, Wellington Street, North Strand,Wednesday, April 12th, 1854.* * * * * *I know all the walks for many and many miles round about Malvern, and delightful walks they are. I suppose you are already getting very stout, very red, very jovial (in a physical point of view) altogether.

Mark and I walked to Dartford from Greenwich, last Monday, and found Mrs. – acting "The Stranger" (with a strolling company from the Standard Theatre) in Mr. Munn's schoolroom. The stage was a little wider than your table here, and its surface was composed of loose boards laid on the school forms. Dogs sniffed about it during the performances, and the carpenter's highlows were ostentatiously taken off and displayed in the proscenium.

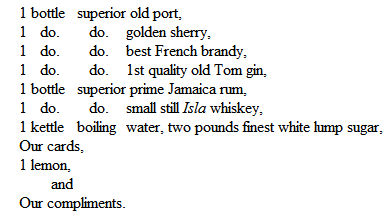

We stayed until a quarter to ten, when we were obliged to fly to the railroad, but we sent the landlord of the hotel down with the following articles:

The effect we had previously made upon the theatrical company by being beheld in the first two chairs – there was nearly a pound in the house – was altogether electrical.

My ladies send their kindest regards, and are disappointed at your not saying that you drink two-and-twenty tumblers of the limpid element, every day. The children also unite in "loves," and the Plornishghenter, on being asked if he would send his, replies "Yes – man," which we understand to signify cordial acquiescence.

Forster just come back from lecturing at Sherborne. Describes said lecture as "Blaze of Triumph."

H. W. againMiss – I mean Mrs. – Bell's story very nice. I have sent it to the printer, and entitled it "The Green Ring and the Gold Ring."

This apartment looks desolate in your absence; but, O Heavens, how tidy!

F. WMrs. Wills supposed to have gone into a convent at Somers Town.

My dear Wills,Ever faithfully yours.Mr. B. W. ProcterTavistock House, Saturday Night, April 15th, 1854.My dear Procter,

I have read the "Fatal Revenge." Don't do what the minor theatrical people call "despi-ser" me, but I think it's very bad. The concluding narrative is by far the most meritorious part of the business. Still, the people are so very convulsive and tumble down so many places, and are always knocking other people's bones about in such a very irrational way, that I object. The way in which earthquakes won't swallow the monsters, and volcanoes in eruption won't boil them, is extremely aggravating. Also their habit of bolting when they are going to explain anything.

You have sent me a very different and a much better book; and for that I am truly grateful. With the dust of "Maturin" in my eyes, I sat down and read "The Death of Friends," and the dust melted away in some of those tears it is good to shed. I remember to have read "The Backroom Window" some years ago, and I have associated it with you ever since. It is a most delightful paper. But the two volumes are all delightful, and I have put them on a shelf where you sit down with Charles Lamb again, with Talfourd's vindication of him hard by.

We never meet. I hope it is not irreligious, but in this strange London I have an inclination to adapt a portion of the Church Service to our common experience. Thus:

"We have left unmet the people whom we ought to have met, and we have met the people whom we ought not to have met, and there seems to be no help in us."

But I am always, my dear Procter,(At a distance),Very cordially yours.Mrs. GaskellTavistock House, April 21st, 1854.My dear Mrs. Gaskell,

I safely received the paper from Mr. Shaen, welcomed it with three cheers, and instantly despatched it to the printer, who has it in hand now.

I have no intention of striking. The monstrous claims at domination made by a certain class of manufacturers, and the extent to which the way is made easy for working men to slide down into discontent under such hands, are within my scheme; but I am not going to strike, so don't be afraid of me. But I wish you would look at the story yourself, and judge where and how near I seem to be approaching what you have in your mind. The first two months of it will show that.

I will "make my will" on the first favourable occasion. We were playing games last night, and were fearfully clever. With kind regards to Mr. Gaskell, always, my dear Mrs. Gaskell,

Faithfully yours.Mr. Frank Stone, A.R.ATavistock House, May 30th, 1854.My dear Stone,

I cannot stand a total absence of ventilation, and I should have liked (in an amiable and persuasive manner) to have punched – 's head, and opened the register stoves. I saw the supper tables, sir, in an empty state, and was charmed with them. Likewise I recovered myself from a swoon, occasioned by long contact with an unventilated man of a strong flavour from Copenhagen, by drinking an unknown species of celestial lemonade in that enchanted apartment.

I am grieved to say that on Saturday I stand engaged to dine, at three weeks' notice, with one – , a man who has read every book that ever was written, and is a perfect gulf of information. Before exploding a mine of knowledge he has a habit of closing one eye and wrinkling up his nose, so that he seems perpetually to be taking aim at you and knocking you over with a terrific charge. Then he looks again, and takes another aim. So you are always on your back, with your legs in the air.

How can a man be conversed with, or walked with, in the county of Middlesex, when he is reviewing the Kentish Militia on the shores of Dover, or sailing, every day for three weeks, between Dover and Calais?

Ever affectionately.P.S. – "Humphry Clinker" is certainly Smollett's best. I am rather divided between "Peregrine Pickle" and "Roderick Random," both extraordinarily good in their way, which is a way without tenderness; but you will have to read them both, and I send the first volume of "Peregrine" as the richer of the two.

Mr. Peter CunninghamTavistock House, June 7th, 1854.My dear Cunningham,

I cannot become one of the committee for Wilson's statue, after entertaining so strong an opinion against the expediency of such a memorial in poor dear Talfourd's case. But I will subscribe my three guineas, and will pay that sum to the account at Coutts's when I go there next week, before leaving town.

"The Goldsmiths" admirably done throughout. It is a book I have long desired to see done, and never expected to see half so well done. Many thanks to you for it.

Ever faithfully yours.P.S. – Please to observe the address at Boulogne: "Villa du Camp de Droite."

Mr. W. H. WillsVilla du Camp de Droite, Thursday, June 22nd, 1854.My dear Wills,

I have nothing to say, but having heard from you this morning, think I may as well report all well.

We have a most charming place here. It beats the former residence all to nothing. We have a beautiful garden, with all its fruits and flowers, and a field of our own, and a road of our own away to the Column, and everything that is airy and fresh. The great Beaucourt hovers about us like a guardian genius, and I imagine that no English person in a carriage could by any possibility find the place.

Of the wonderful inventions and contrivances with which a certain inimitable creature has made the most of it, I will say nothing, until you have an opportunity of inspecting the same. At present I will only observe that I have written exactly seventy-two words of "Hard Times," since I have been here.

The children arrived on Tuesday night, by London boat, in every stage and aspect of sea-sickness.

The camp is about a mile off, and huts are now building for (they say) sixty thousand soldiers. I don't imagine it to be near enough to bother us.

If the weather ever should be fine, it might do you good sometimes to come over with the proofs on a Saturday, when the tide serves well, before you and Mrs. W. make your annual visit. Recollect there is always a bed, and no sudden appearance will put us out.

Kind regards.Ever faithfully.Mr. W. Wilkie CollinsVilla du Camp de Droite, Boulogne,Wednesday Night, July 12th, 1854.My dear Collins,

Bobbing up, corkwise, from a sea of "Hard Times" I beg to report this tenement – amazing!!! Range of view and air, most free and delightful; hill-side garden, delicious; field, stupendous; speculations in haycocks already effected by the undersigned, with the view to the keeping up of a "home" at rounders.

I hope to finish and get to town by next Wednesday night, the 19th; what do you say to coming back with me on the following Tuesday? The interval I propose to pass in a career of amiable dissipation and unbounded license in the metropolis. If you will come and breakfast with me about midnight – anywhere – any day, and go to bed no more until we fly to these pastoral retreats, I shall be delighted to have so vicious an associate.

Will you undertake to let Ward know that if he still wishes me to sit to him, he shall have me as long as he likes, at Tavistock House, on Monday, the 24th, from ten a. m.?

I have made it understood here that we shall want to be taken the greatest care of this summer, and to be fed on nourishing meats. Several new dishes have been rehearsed and have come out very well. I have met with what they call in the City "a parcel" of the celebrated 1846 champagne. It is a very fine wine, and calculated to do us good when weak.

The camp is about a mile off. Voluptuous English authors reposing from their literary fatigues (on their laurels) are expected, when all other things fail, to lie on straw in the midst of it when the days are sunny, and stare at the blue sea until they fall asleep. (About one hundred and fifty soldiers have been at various times billeted on Beaucourt since we have been here, and he has clinked glasses with them every one, and read a MS. book of his father's, on soldiers in general, to them all.)

I shall be glad to hear what you say to these various proposals. I write with the Emperor in the town, and a great expenditure of tricolour floating thereabouts, but no stir makes its way to this inaccessible retreat. It is like being up in a balloon. Lionising Englishmen and Germans start to call, and are found lying imbecile in the road halfway up. Ha! ha! ha!

Kindest regards from all. The Plornishghenter adds Mr. and Mrs. Goose's duty.

Ever faithfully.P.S. – The cobbler has been ill these many months, and unable to work; has had a carbuncle in his back, and has it cut three times a week. The little dog sits at the door so unhappy and anxious to help, that I every day expect to see him beginning a pair of top boots.

Miss HogarthOffice of "Household Words," Saturday, July 22nd, 1854.My dear Georgina,

Neither you nor Catherine did justice to Collins's book.17 I think it far away the cleverest novel I have ever seen written by a new hand. It is in some respects masterly. "Valentine Blyth" is as original, and as well done as anything can be. The scene where he shows his pictures is full of an admirable humour. Old Mat is admirably done. In short, I call it a very remarkable book, and have been very much surprised by its great merit.

Tell Kate, with my love, that she will receive to-morrow in a little parcel, the complete proofs of "Hard Times." They will not be corrected, but she will find them pretty plain. I am just now going to put them up for her. I saw Grisi the night before last in "Lucrezia Borgia" – finer than ever. Last night I was drinking gin-slings till daylight, with Buckstone of all people, who saw me looking at the Spanish dancers, and insisted on being convivial. I have been in a blaze of dissipation altogether, and have succeeded (I think), in knocking the remembrance of my work out.

Loves to all the darlings, from the Plornish-Maroon upward. London is far hotter than Naples.

Ever affectionately.Mrs. GaskellVilla du Camp de Droite, Boulogne,Thursday, Aug. 17th, 1854.My dear Mrs. Gaskell,

I sent your MS. off to Wills yesterday, with instructions to forward it to you without delay. I hope you will have received it before this notification comes to hand.

The usual festivity of this place at present – which is the blessing of soldiers by the ten thousand – has just now been varied by the baptising of some new bells, lately hung up (to my sorrow and lunacy) in a neighbouring church. An English lady was godmother; and there was a procession afterwards, wherein an English gentleman carried "the relics" in a highly suspicious box, like a barrel organ; and innumerable English ladies in white gowns and bridal wreaths walked two and two, as if they had all gone to school again.

At a review, on the same day, I was particularly struck by the commencement of the proceedings, and its singular contrast to the usual military operations in Hyde Park. Nothing would induce the general commanding in chief to begin, until chairs were brought for all the lady-spectators. And a detachment of about a hundred men deployed into all manner of farmhouses to find the chairs. Nobody seemed to lose any dignity by the transaction, either.

With kindest regards, my dear Mrs. Gaskell,Faithfully yours always.Rev. William HarnessVilla du Camp de Droite, Boulogne,Saturday, Aug. 19th, 1854.My dear Harness,

Yes. The book came from me. I could not put a memorandum to that effect on the title-page, in consequence of my being here.

I am heartily glad you like it. I know the piece you mention, but am far from being convinced by it. A great misgiving is upon me, that in many things (this thing among the rest) too many are martyrs to our complacency and satisfaction, and that we must give up something thereof for their poor sakes.

My kindest regards to your sister, and my love (if I may send it) to another of your relations.

Always, very faithfully yours.Mr. Henry AustinVilla du Camp de Droite, Boulogne,Wednesday, Sept. 6th, 1854.* * * * * *Any Saturday on which the tide serves your purpose (next Saturday excepted) will suit me for the flying visit you hint at; and we shall be delighted to see you. Although the camp is not above a mile from this gate, we never see or hear of it, unless we choose. If you could come here in dry weather you would find it as pretty, airy, and pleasant a situation as you ever saw. We illuminated the whole front of the house last night – eighteen windows – and an immense palace of light was seen sparkling on this hill-top for miles and miles away. I rushed to a distance to look at it, and never saw anything of the same kind half so pretty.

The town18 looks like one immense flag, it is so decked out with streamers; and as the royal yacht approached yesterday – the whole range of the cliff tops lined with troops, and the artillery matches in hand, all ready to fire the great guns the moment she made the harbour; the sailors standing up in the prow of the yacht, the Prince in a blazing uniform, left alone on the deck for everybody to see – a stupendous silence, and then such an infernal blazing and banging as never was heard. It was almost as fine a sight as one could see under a deep blue sky. In our own proper illumination I laid on all the servants, all the children now at home, all the visitors (it is the annual "Household Words" time), one to every window, with everything ready to light up on the ringing of a big dinner-bell by your humble correspondent. St. Peter's on Easter Monday was the result.

Best love from all.Ever affectionately.Mr. W. Wilkie CollinsBoulogne, Tuesday, Sept. 26th, 1854.My dear Collins,

First, I have to report that I received your letter with much pleasure.

Secondly, that the weather has entirely changed. It is so cool that we have not only a fire in the drawing-room regularly, but another to dine by. The delicious freshness of the air is charming, and it is generally bright and windy besides.

Thirdly, that – 's intellectual faculties appear to have developed suddenly. He has taken to borrowing money; from which I infer (as he has no intention whatever of repaying) that his mental powers are of a high order. Having got a franc from me, he fell upon Mrs. Dickens for five sous. She declining to enter into the transaction, he beleaguered that feeble little couple, Harry and Sydney, into paying two sous each for "tickets" to behold the ravishing spectacle of an utterly-non-existent-and-there-fore-impossible-to-be-produced toy theatre. He eats stony apples, and harbours designs upon his fellow-creatures until he has become light-headed. From the couch rendered uneasy by this disorder he has arisen with an excessively protuberant forehead, a dull slow eye, a complexion of a leaden hue, and a croaky voice. He has become a horror to me, and I resort to the most cowardly expedients to avoid meeting him. He, on the other hand, wanting another franc, dodges me round those trees at the corner, and at the back door; and I have a presentiment upon me that I shall fall a sacrifice to his cupidity at last.

On the Sunday night after you left, or rather on the Monday morning at half-past one, Mary was taken very ill. English cholera. She was sinking so fast, and the sickness was so exceedingly alarming, that it evidently would not do to wait for Elliotson. I caused everything to be done that we had naturally often thought of, in a lonely house so full of children, and fell back upon the old remedy; though the difficulty of giving even it was rendered very great by the frightful sickness. Thank God, she recovered so favourably that by breakfast time she was fast asleep. She slept twenty-four hours, and has never had the least uneasiness since. I heard – of course afterwards – that she had had an attack of sickness two nights before. I think that long ride and those late dinners had been too much for her. Without them I am inclined to doubt whether she would have been ill.

Last Sunday as ever was, the theatre took fire at half-past eleven in the forenoon. Being close by the English church, it showered hot sparks into that temple through the open windows. Whereupon the congregation shrieked and rose and tumbled out into the street; – benignly observing to the only ancient female who would listen to him, "I fear we must part;" and afterwards being beheld in the street – in his robes and with a kind of sacred wildness on him – handing ladies over the kennel into shops and other structures, where they had no business whatever, or the least desire to go. I got to the back of the theatre, where I could see in through some great doors that had been forced open, and whence the spectacle of the whole interior, burning like a red-hot cavern, was really very fine, even in the daylight. Meantime the soldiers were at work, "saving" the scenery by pitching it into the next street; and the poor little properties (one spinning-wheel, a feeble imitation of a water-mill, and a basketful of the dismalest artificial flowers very conspicuous) were being passed from hand to hand with the greatest excitement, as if they were rescued children or lovely women. In four or five hours the whole place was burnt down, except the outer walls. Never in my days did I behold such feeble endeavours in the way of extinguishment. On an average I should say it took ten minutes to throw half a gallon of water on the great roaring heap; and every time it was insulted in this way it gave a ferocious burst, and everybody ran off. Beaucourt has been going about for two days in a clean collar; which phenomenon evidently means something, but I don't know what. Elliotson reports that the great conjuror lives at his hotel, has extra wine every day, and fares expensively. Is he the devil?