Полная версия:

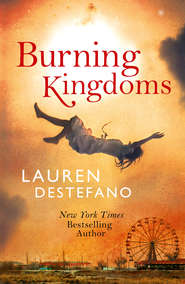

Burning Kingdoms

I understand why the professor won’t leave it.

In my observing, I’ve wandered away from the others, but Nimble has followed me. “I’m impressed that it flew,” he says.

“Me too,” I say. “I might not have boarded it if I’d had much of a choice.”

I shut my mouth immediately. I’ve said too much. What will Jack Piper and his family do if they realize we’re all fugitives? All of us but the princess, anyway, and Thomas, who was dragged along as her hostage.

Then again, what would it matter to anyone down here how the people carry about on that tiny floating rock so very high above them?

“Sounds as though there was some trouble in paradise,” Nimble says.

“Paradise?”

“Your perfect little island,” he says, nodding upward. I follow his gaze, hoping for a glimpse of Internment. But there’s only a sky heavy with clouds. These clouds are not like the ones I know—light airy things that soared around and over me every day. These clouds are burdened and gray, and I sense that they are grieving.

“There are no perfect places,” I say. The clouds move away from the sun just enough for the light to blind me, and I shield my eyes.

“You know that and I know that,” he says. “Try telling our king, and you’ll be run out of the kingdom. He thinks that if we plan an aerial attack over the right places, once the ashes clear, we’ll be in our own utopia.”

I don’t know the capabilities of a bomb, but surely it wouldn’t take much to destroy a small city like Internment.

“Firecrackers, bombs,” I say. “You people sure do like things that burn.”

“I imagine there aren’t many fires on Internment?” he says.

“Even a small one is cause to panic,” I say. I suppose something like the fire at the flower shop would be nothing to the people down here, but it was enough to throw all of Internment into upheaval.

I can feel his gaze on me as I look for a trace of Internment in the sky. I know what he’s thinking. That we were foolish to come here. We left our safe little island and descended straight into a kingdom at war. But while they fight with explosives down here, different battles are being waged in the sky. Silent revolutions. Equally silent murders.

“You don’t know anything,” I whisper. I’m not sure if the words are for him, or for me.

The door of the metal bird creaks open and Amy descends the ladder alone. She’s talking to Jack and his men, and by their disappointed expressions it becomes clear that her attempt to lure the professor out wasn’t a successful one.

“All right, all right. It looks like there will be another storm coming. Let’s reconvene once I’ve spoken to His Majesty. Nim, please see our guests home.”

“Can do, Father.”

Once we’re back in the car, Amy says, “My grandfather will come out in time. He’s just got an awful lot of love for that metal bird. He’s afraid they’ll destroy it if he leaves.”

“What makes you so sure he’ll come out, then?” Nimble asks.

“He’ll run out of food soon. He asked me to bring him some more just now, and I told him that if he wants to eat, he’ll have to come out.” She dusts the snow from the shoulders of her plaid coat.

“But if he’s so stubborn, what makes you sure he won’t starve to death rather than come out?” Nimble says.

“He won’t. He’s far too curious about this place. He’ll be taking a magnifying glass to the insects and collecting soil samples soon enough. You’ll see.”

The car starts to move. Overhead, the sky has begun to darken. The sun is behind the clouds like light trying to hatch from an egg. I feel as though I’m being smothered.

Amy seems better now, though. Her eyes are their usual blue and her mouth hangs open as she watches the city in the distance.

“What did you call that place where you bury your dead?” she asks.

“A graveyard,” Nimble says.

“Can anyone visit?”

“You want to visit the graveyard?” he says.

“If I can.”

“I guess it can’t hurt,” Nimble says. “It’s not much to see, though. People go to visit their loved ones, and kids go at night to spook each other, and that’s all the action these places get.”

“Do you always bury your dead?” I say, trying to hide how appalling I think the whole thing is.

“Not always,” Nimble says, his tone cheery to the point of sarcasm. “Sometimes we cremate. I’m guessing that’s what your kind does up there, with so little land.”

“It makes the most sense,” I say.

“It isn’t that we don’t like to burn stuff down here,” Nimble says. “Most homes have a fire altar. There’s one at the hotel, in fact. Even guests use it.”

“You burn bodies out on your lawn?” I say, my stomach beginning to turn.

“Not bodies. Offerings,” Nimble says. “If there’s something you really want to ask of our god, you burn something that’s of equal importance to you.”

At last a ritual I don’t find wasteful. It seems poetic, even. “We have something like that on Internment,” I say. “Once a year we burn our highest request and set it up on the wind to be heard.”

“Once a year.” Nim whistles. “You could burn things all day down here if you wanted. People have no shortage of things to ask for.”

“So you burn things often, then,” I say.

“I don’t, personally. Don’t take much stock in it.”

As soon as the car has stopped at the graveyard, Amy is gone, leaving the open car door behind her to fill the car with cold.

“We won’t be long,” I say apologetically. I don’t expect him to understand a girl like Amy. He can’t appreciate what the edge has done to her.

I expect some sort of judgment or another remark about how odd she is, but “I’ll keep the car warm for you,” is all he says.

The graveyard is framed by hedges, and the entrance is through a pair of elaborate iron doors ingrained with flying children holding some sort of stringed instrument.

Amy is knelt in the snow when I find her. She clears away the brambles until the words on the headstone before her are revealed. “Lila Pike. It says she died the year she was born,” Amy says.

“That’s miserable,” I say.

“I wonder what happened.”

I don’t.

I look up from the stone. It is only one among hundreds of untold stories. Names, dates, flowers in vases left to wilt under all this white.

There’s so much land on the ground that they can make a garden of all their dead. It’s no matter whether anyone ever comes to visit.

Amy looks over her shoulder at me. Her brow is raised. “What do you think happens when they bury you here, and years pass, and everyone who knew you is dead? Who comes to visit? Or do they mow this down and start over?”

“I don’t know,” I say. “It seems like such a waste—all of it.”

“Maybe not,” Amy says. “If there were a place I could go and visit my sister, talk to her—I think I’d like that.”

“I don’t think I could visit my parents in a place like this,” I say. “There are no spirits here. Only stones.”

“There are spirits,” Amy says with certainty. “But these spirits aren’t our spirits.”

I don’t know what she means. She’s a peculiar little girl who says peculiar things, but her outlandish remarks are different from the kind that other children tell. She speaks assuredly. And when she awakens from her fits, there’s real sadness, and that sadness lingers with her for days.

And though I don’t entirely believe in the things she claims, I don’t think it’s all her imagination. A normal girl would want to imagine happy things.

A breeze disturbs the bare branches and I hug my arms when it reaches me.

I’d much like to leave now, but Amy may well miss out on much of the exploring, due to her fits and Judas’s overprotectiveness, and if this is all she wants, she should get to see it.

The wind picks up, as though it means to force us away. The rusted gate swings on its hinge, an invitation to leave.

But the squealing gate isn’t the only noise. There’s a low whistle, and then a crack so loud Amy jumps to her feet. “What was that?” she says. Another crack. Louder, so much louder, than the thunder that horrified us the other night when we heard it for the first time.

Straight ahead of us, the headstones make a path to the horizon. They offer no answers. And they have no reaction to that black billowing smoke where a building stood only seconds ago.

I think of what Nimble said. Bomb.

“Come on!” I grab her arm and run for the gate. I don’t look back. She’s gasping for breath beside me, but she manages to keep up. I have a fleeting thought that this could trigger one of her fits, but I don’t know what caused that explosion or if there will be another.

The day the flower shop caught fire, I thought it had the power to end my little world. How was I to know that there were bigger fires happening below us? I don’t know what it would take to end a world this size, if anything could. All I’ve seen are more terrifying ways to destroy, to no end at all.

Nimble is speeding away even before I’ve had a chance to close the door. The car lurches and swerves on the ice.

“Looks like you ladies arrived just in time for the fun to begin,” he says.

4

The black clouds are visible from the hotel by the time we’ve returned to it. I see them rolling in the distance, moving the way that giant body of water moves, snuffing out the bereft gray clouds. The sun has made a wise decision to hide from us completely.

The car jolts to a stop by the front door. “Go on inside,” Nimble says.

“Aren’t you coming?” I ask.

“After I park,” he says. “Aerial warfare’s bad for the paint.”

The front door swings open and there the Piper children stand, perfectly in order, all of them with the same frightened eyes. “Nim!” Birdie calls as he speeds around the building.

“Where’s he going?” Riles asks.

“To park in the carriage house. Him and his love for that stupid bus,” Birdie says.

“I’ll help,” Riles says, but Birdie catches him by the collar as he tries to run outside.

“Don’t be a pest.” She ruffles his hair. “Leave the door open for him.”

“What happened?” Basil says.

Everyone is full of questions. Everyone is talking. The words bounce off my skin, never reaching me, not really. I move to the nearest window and I step behind those gold curtains to watch the smoke blend into the sky.

“It’s like the flower shop fire times a thousand, isn’t it?” Celeste’s voice startles me. She’s standing beside me, both of us tented off from the others.

“You wouldn’t know, would you?” I say. “Or did you see it from your clock tower window?”

“I was out hunting with my brother that day, I’ll have you know,” she says. “True, we were some distance away, but I could smell the smoke.”

Snapping at the princess won’t do any good. Even if her father and his henchmen did start that fire in an attempt to cease the rebellion, she had nothing to do with it. She hasn’t made her sinister side a secret, but when she held Pen and me hostage, I got a sense for how little she knew of her father’s plans. She wasn’t interested in or aware of any of them. She only wanted me to help her get to the ground. Nothing more.

“So this is what you left your floating kingdom for,” I say, nodding ahead. “Are you glad you came?”

She takes a deep breath, straightens her shoulders. “I understand that you’re frightened, so I’m going to let this bitterness slide,” she says. “But I’ll have you know that you’re beginning to sound like that brazen friend of yours, and I know you’re better than that. Anyway, I wasn’t looking to argue.”

“What were you looking for, then?” I say.

“I wanted to check on you, of course,” she says.

I look at her from the corners of my eyes.

“Oh, all right. I also wanted to ask what you saw out there.”

“I heard an explosion and then I saw the smoke,” I say. “Nimble called it an aerial attack.”

Celeste arranges her thumbs and index fingers like a frame and holds them to the glass, considering. “Do you suppose this has been going on below us the whole time?” she says.

“I don’t know,” I say. “I don’t know how anyone can live in a world where this happens frequently.”

Celeste looks at me. Her smile is toothy and bright. “Then we’ve come just in time to save them, wouldn’t you say?”

I bring a tray of food to Alice and Lex. I can’t think of any other way to make myself useful. I tell them about the explosion, and the smoke. And I tell them about the graveyard.

How much can the people of the ground value life when they have so much land with which to bury their dead? What’s a few more stones? But I don’t say that. “The princess thinks we can help them,” is what I say.

Alice looks concerned. “Did she say why she came with us?”

“No,” I say. “But she seemed pretty desperate. Enough that she interrogated Pen and me, and held Thomas at knifepoint so we wouldn’t kick her off the bird.”

Lex’s transcriber sits on the floor near the bed, and the lack of smell that its coppery motor usually emits tells me he hasn’t used it since we arrived. We all left in a hurry the night I was poisoned. I was unconscious and dying in Basil’s arms. But Alice thought to grab the one thing that will surely keep Lex sane; she must have known there would be no turning back.

Lex sits on the floor beside the thing, his legs folded, worrying a square metal clock in his hands. The ticking provides an anchor, reminds him that even in his persistent darkness, the seconds never cease. He doesn’t need to know the hour; he only needs to know that they’re still passing.

“This war may just be getting started,” Alice says.

“Basil says that the Pipers will want to collect on their kindness in taking us in,” I say. “I’ve been giving it a lot of thought, but I can’t imagine how we could help. It isn’t as though we have any more ties to home than they do. We can’t go back.”

“They don’t know that,” Lex says. His head is down, and his voice is scratchy. “We’d better hope they don’t figure out how powerless we are.”

Alice frowns into her tea. Then she kneels before Lex and replaces the clock in his hands with the cup. “Drink this,” she says. “And then we should eat something. We’re going to need our strength.”

“Strength for what?” Lex says.

“For living,” she says, with that persistent vivacity I’ve always loved her for. “I don’t know what’s to come, but we’d better prepare ourselves to face it.” She brings the cup to his lips, forcing it on him. She kisses his forehead when he scowls at her. “Drink it.”

Hours pass and Jack Piper doesn’t return. The smaller children occupy themselves with some sort of game that involves a board of squares.

Nimble enters through the front door.

“I didn’t realize you’d gone outside,” Birdie says, looking up from her mathematics sheet.

He’s tucking a cloth into his pocket. “There was a smudge on the seat of the car that was nagging me.”

“You risked your safety going outside for that? After a bombing? Sometimes I think you value that car more than you do us.”

“Don’t be silly, Birds,” he says, and flicks her hair. “Of course I care more about the car.”

She rolls her eyes, blows at a bit of eraser dust on the page.

That car is his only haven, I realize. The Piper children live in this very large home, and yet every corner belongs to their father, and every move they make is scrutinized. That small place belongs only to Nimble, though, and it can take him anywhere he may ever wish to go.

Some phantom part of me keeps expecting a patrolman to come around and turn on the screen so there can be a broadcast with some news. But there are no patrolmen. There are no screens. There’s only something called a transistor radio, the knobs of which are arranged to make a permanently startled face. And it isn’t giving us any news right now. It’s only playing some sort of jaunty music that reminds me that this is not my home.

Celeste and Nimble sit by the fireplace, stacks of books between them. The pages are open in their laps, but they’re looking at each other. I catch bits of what they’re saying. Kings. Death. Something called a biplane. She is fascinated and excited.

Basil, Pen, Thomas, and I sit together on the lush floor. A carpet, they call it; it’s nothing at all like the tiny rugs my mother and Lex used to weave from old clothing scraps. “You know what this reminds me of?” Pen says.

“Don’t tell me you can liken a passage from our history book to this,” Thomas says.

“Of course I can.” She raises her chin. “This is like the story of the dark time. Hundreds of years ago, Phinneas Hart discovered a way to store the sun’s energy and use it as fuel. He knew it would revolutionize the way Internment worked, but his greedy brother, the banker, advised him to charge money for the new technology. The god of the sky was so displeased by this display of greed that the sky filled with clouds, and the clouds covered the sun completely. Crops wilted. Children and the elderly grew ill first, but slowly the illness began to overtake everyone.

“Phinneas recognized what was happening, and he abandoned his brother’s ideas, and he toiled for months laying the groundwork for the glasslands, and he wouldn’t take a page of money for it.”

“Yes, I’ve always found that story a bit hard to believe,” Thomas says.

“Because you’re a heathen,” Pen says. “In any case, the god of the sky returned the sunlight with a warning about charging for what should be free. If people were going to be greedy, he could take the source of that greed away. That’s why it’s against the law for any king to pass a bill that would charge for wind or solar energy.”

“Why does this remind you of the dark time?” Basil asks.

Pen stares at her betrothal band, twisting it round and round her finger. “Because,” she says. “This is what happens when there’s greed. Everything gets destroyed until there’s nothing left to take.”

Thomas puts his arm around her shoulders, and in a rare display of fondness she leans against him.

“It isn’t as bad as all that,” I tell her, though I don’t entirely believe it. “The ground is much bigger than Internment. These bombs couldn’t possibly end it all.”

“Don’t you see it?” she says. “All this space has made them cocky. Look at how big their houses are. Look at how many children they have. A cloud of smoke and a few explosions are only the start, Morgan. These people are doomed, and it doesn’t matter where we’re from. We’re along for the ride now, all of us.”

“I’m so fortunate to be betrothed to an optimist,” Thomas says.

She sighs, irritated. “Don’t take me seriously, then. You’ll see.”

“I do take you seriously, Pen. I just worry you’ll go spiraling if you talk like this.”

She opens her mouth to argue, but I say, “Let’s see if the others will let us join their game.”

For me, Pen relinquishes her side of the argument.

The board games are all simple, quick, and mindless. Birdie often forgets it’s her turn because she’s staring worriedly at the door. When it finally opens, she about jumps from her skin. She rushes to take her father’s coat.

Nimble looks up from his book. “What did you find out?”

“The banks are gone,” Jack says.

“The hospital?”

“No, though it may only be a matter of time.”

Marjorie, Riles, and Annette are wide-eyed, and Jack smiles at them. “Nothing to be alarmed about, children,” he says. “It’s all just a game that our King Ingram is playing with King Erasmus.”

“What will the winner get?” Annette asks.

“Something very precious,” Jack says. “A very important place.” He nods to Celeste, who is rising to her feet from across the room. “Princess, if I may speak with you privately,” he says.

“Certainly,” she says. She follows him from the room, Nimble at her heels. Birdie rushes after them, only to have the door closed in her face.

She scowls and presses her ear to the door, nearly stumbling when it opens and Nimble pokes his head out at her. “Father says to go on and have dinner without us.”

“But—”

The door closes again.

“Riles,” Birdie whispers. He has already read her mind. He scales the back of the couch and climbs onto her shoulders. He’s just high enough now to reach a crack in the plaster wall. He presses his ear to his drinking glass to amplify the sound, and listens. Clearly the two of them have this down to a science.

“Anything?” she asks.

“Not if you keep yapping.”

He listens a few seconds more, and Birdie arches her back uncomfortably. And just when I think she can carry his weight no longer, he climbs down.

“No one died,” Riles says. “That’s all I could get. That’s good, isn’t it?”

Birdie looks worried. “I don’t know,” she says, and then she blinks away her melancholy. “I owe you some ice cream after dinner, but don’t tell your sisters.”

“Pleasure doing business,” he says.

5

“I don’t like this one bit,” Pen says, scouring her face with a wet cloth. “Her Duplicitous Highness has been at conference with Jack Piper for hours now.”

I lie back in the drained tub, letting my legs dangle over the edge. “What do you suppose they’re talking about?” I say.

“If she’s smart, she isn’t telling him all about the way Internment is run. But she’s as dumb as a rock, and she loves to hear her own voice.” Pen begins furiously braiding her hair. “When I think of my mother and all those people up there, I just—I can’t stand it.”

“What?”

“How powerless they’d all be against something like what I saw today. One bomb, and it would all be gone. And down here they fire them off like it’s nothing.”

She drops her braid and struggles to fix it, but she can’t seem to steady her hands.

“Pen.” I reach for her. She sits on the edge of the tub, sulking. I fix her hair. “There’s no sense thinking about it. All the bombs they’ve got on the ground can’t reach Internment. Nothing can. Not even that bird we saw this morning.”

“Not even us,” Pen whispers, broken.

I wrap my arms around her waist and pull her into the tub with me. I was hoping to make her laugh, but she flops unceremoniously against me.

“Tell me another story from the history book,” I say. “What about the tree that grew endless fruit after the infestation killed the crops?”

“It wasn’t an infestation,” Pen says. “You always get that part confused. It was a drought. The lakes weren’t replenishing. The people were losing faith in the god of the sky. Fish were rotting in the sun.”

“And then?” I say.

“You know the story,” she sighs. She flails until she’s able to free herself from the tub. “I’m going to bed.”

She reaches her hand out to me, and I let her pull me to my feet. I’m not tired at all, but there isn’t anything more to do. The sooner we sleep, the sooner it will be morning. And maybe there will be some answers then.

Celeste still hasn’t returned by the time I turn out the light. Pen’s bed and mine are separated by a small table that holds a black book and an alarm clock. The ticking feels louder in the darkness, drowned only by Pen’s tosses and turns.

I don’t move. Guilt has made me fear the days to come. If experiencing this war is the price I must pay for my curiosity, then I accept. But Pen never asked for this. Nor did Basil and Thomas. And they’re all here, one way or another, because of me.

The door creaks open, letting in the faint glow of the fireplace down in the lobby.

“About bloody time, Princess,” Pen mutters. “Don’t even think about blinding us with the light.”

“It’s me,” Birdie whispers. “I’m sorry, but Father is still downstairs and I—I need that tree.”

She sounds as frightened as I feel.

I sit up. “Is it safe to be out there?”

“I don’t care about safe,” she says.

“We have something in common, then,” Pen says. “Take us with you.”

“Or you’ll tell on me?” Birdie says unhappily.