Полная версия:

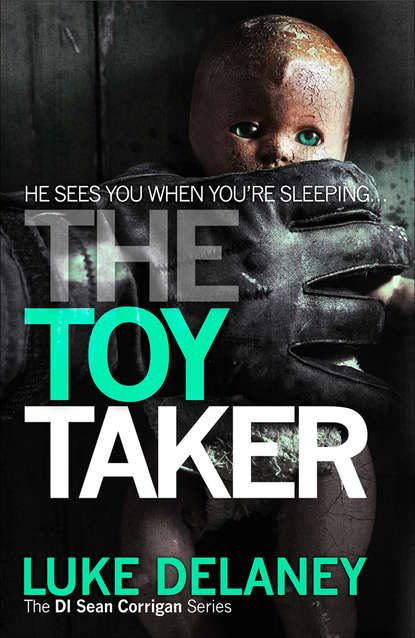

The Toy Taker

‘I’ve just been speaking with the Beiersdorfs from number 5. I took the liberty of asking them your name. I hope you don’t mind.’

‘No,’ she lied. ‘I assume this is about the little boy from next door?’

‘You heard then?’

‘Couldn’t help hearing with all the police walking up and down the street. Have you found him yet?’

‘No,’ Donnelly answered. ‘Sadly not.’

‘His poor mother,’ Mrs Howells said without feeling, ‘she must be besides herself with worry.’

‘She’s holding up. Sorry I didn’t catch your first name.’

‘Philippa,’ she told him.

‘Well, Philippa, I was wondering if I could come inside and speak with you a minute?’

‘It’s very late. I was expecting someone from the police to call here earlier. Perhaps you could come back tomorrow?’

‘Better to get it out of the way now,’ Donnelly quickly told her, sensing she was about to close the door. ‘Anything that might help us find the little boy – right?’

‘Very well,’ she relented, flicking the chain off the hook and swinging the door open for him. ‘You’d better come inside.’

‘That’s very kind of you,’ Donnelly said as he skipped up the stairs. ‘Is Mr Howells also at home by any chance?’ he asked.

‘No,’ she answered curtly while closing the door, ‘he’s away on business.’

‘Pity,’ he told her. ‘Ideally I would have liked to speak to both of you.’

‘I don’t suppose my husband would know any more than I do,’ she explained, leading him through the house to the large kitchen diner – a common feature in the houses of the street. ‘We hardly know them − they only moved in a few weeks ago. But I suppose you already know that. Please, take a seat,’ she told him, indicating a stool at the breakfast bar.

‘And you popped round to introduce yourself?’ Donnelly asked, keen to speed things along.

‘Of course. This is a friendly street. We had a street party for the Jubilee and every Christmas we have a big party for all the kids at the local tennis club, that sort of thing.’

‘But the Bridgemans didn’t want to know?’

‘You could say that. She seemed keener than her husband, but not exactly over-friendly.’

‘So the husband seemed to be the one wanting them to keep their distance – is that fair?’

‘I suppose so,’ she answered. ‘I assumed they were just shy and preferred to keep themselves to themselves.’

‘Fair enough,’ Donnelly encouraged.

‘Exactly, but they’d only been here a few days when … well, quite frankly, the arguments started. Believe me, the walls of these houses are pretty solid, but you could still hear them – or rather him.’

‘So it was Mr Bridgeman doing the shouting?’

‘She joined in, but yes, mainly him.’

‘Could you hear what they were arguing about?’

‘Not really, although I did hear him calling her a lying bitch one time. I think at that point my husband and I vowed to have as little to do with them as possible and that’s the way it’s been.’

‘What about the kids? How did they seem?’

‘All right, considering.’

‘And the children’s behaviour?’

‘Fine. The little girl …’

‘Sophia.’

‘Yes, Sophia, seemed to have a lot to say for herself, but the little boy …’

‘George.’

‘Yes, sorry, George was a very quiet boy, from what I could tell. But like I said, we don’t really know them.’

‘But on the occasions you did see them,’ Donnelly pressed, ‘maybe in the back garden or out the front there, how did the parents seem towards the children?’ Donnelly’s chirping mobile broke the flow of questions and answers, making him curse under his breath. The caller ID told him it was Sean. He answered without excusing himself. ‘Guv’nor.’

‘Where are you?’ Sean asked.

‘Door-to-door, as assigned. Speaking to the Bridgemans’ neighbours, who are being very helpful,’ he added for the benefit of the listening Mrs Howells.

‘Good,’ Sean told him. ‘While you’re doing that you should bear in mind the house has now been searched properly and the boy hasn’t been found.’

Donnelly cursed inwardly twice: once for not being right about the boy’s body being found in the house and again for not making sure DC Goodwin tipped him off about the search before he told Sean. The news must have come through while he was in with the Beiersdorfs. Damn it. Not to worry. His theory still held water. After killing the boy the Bridgemans could have easily moved the body from the house – perhaps to a secure place while they waited for the heat to die down before getting rid of it permanently. Or maybe they had already disposed of it. ‘Is that so,’ he finally answered.

‘Yes, and the one we have in custody is shaping up nicely,’ Sean continued.

‘Has he admitted it yet?’ Donnelly asked, disappointment at the prospect of being proved wrong mingling with satisfaction that the person responsible was in custody. He had no problem swallowing his pride for the sake of getting a conviction on some sick bastard kiddie-fiddler.

‘No,’ Sean told him. ‘But he hasn’t denied it either, and you have to ask yourself why he wouldn’t deny it if he wasn’t involved.’

‘Because he’s insane?’ Donnelly offered.

‘Not this one,’ Sean explained. ‘He’s wired wrong, but he’s not insane. Seems to want to play games too.’

‘With us?’

‘Apparently. Finish up where you are and try and get some sleep. Tomorrow’s going to be an early start and a late finish, as is every day until we find George – one way or the other.’ Donnelly heard the connection go dead.

‘Sorry about that. Where were we?’ Donnelly asked Mrs Howells.

‘The Bridgeman children,’ she reminded him.

‘Aye, indeed. From what you could see, how did the parents behave towards their children?’

‘OK,’ she answered. ‘Although …’

‘Although what?’ Donnelly seized on it.

‘From the bits and pieces I’ve seen, they were fine towards Sophia, but …’

‘But …?’ he pushed her.

‘Not Celia, but Mr Bridgeman always seemed a little … well, a little cold towards George.’

‘Any idea why?’

‘As I said, I barely know them. I’m just telling you what struck me from the little I’ve observed.’

‘That’s very interesting,’ Donnelly told her. ‘But he’s fine towards Sophia?’

‘Kisses and cuddles on the doorstep when he comes home – plays with her in the garden at the weekends.’

‘Nothing unusual about a daddy’s girl. I have a few kids of my own and my ten-year-old only has eyes for her old dad – much to the annoyance of her mother.’

‘It’s getting very late now,’ Mrs Howells said with a polite smile Donnelly had seen a thousand times before. ‘I really ought to check on the children.’

‘Have you ever seen him, maybe, hit the boy?’ Donnelly ignored her hints.

‘No. No. Of course not.’

‘Ever see him touch George in an inappropriate way?’

‘I really don’t think I should say any more.’

‘Anything you tell me will be treated as confidential, Mrs Howells.’

‘I’ve told you all I know. I never saw him abuse George in any way. It’s just … he was …’

‘Cold towards him,’ Donnelly reminded her.

‘Yes,’ she admitted.

‘And your mother’s instinct told you something was wrong?’ Donnelly tried to seduce her with praise.

‘Yes – I mean no. I’m not sure, really I’m not. It’s late, detective. I must …’

Donnelly tapped the top of the breakfast bar before standing and fastening his overcoat against the cold that waited for him outside. ‘Of course,’ he told her. ‘You’ve been a great help.’

‘I just hope I haven’t misled you,’ she told him.

‘Oh, I don’t think you’ve done that, Mrs Howells. I don’t think you’ve done that at all.’

Sean cursed his nine-to-five neighbours as he searched and failed to find a parking spot anywhere close to the front door of his modest three-bedroom terraced house in East Dulwich, bought just before the wealth spread into the area from Dulwich Village and Blackheath. Maybe Kate was right – they should cash in while it was worth as much as it was and flee to New Zealand; perhaps then he would be able to afford somewhere with off-street parking instead of going through this nightly ritual of imagining his neighbours smugly tucked up in their beds while they thought of him having to park a couple of streets away. At least it wasn’t raining. Finally he parked up and trudged back towards his house, passing cars that he knew would still be parked in the same places as he headed back to his own the next morning. Last home and first to leave – same as usual.

His head was still buzzing with the day’s events: the office move, the new case, meeting the missing boy’s parents, and most of all the interview with McKenzie and all the questions he’d thought of on the way home that he’d forgotten to ask during the interview. He had only a few hours before it would be time to head back to work and pick up where he left off, and experience told him that if he was to get any rest at all he needed to unwind; sit alone and watch something on the TV unrelated to any type of policework while he consumed as much bourbon as he dared to slow his racing mind without leaving him groggy in the morning. To his disappointment, as he entered the house he sensed Kate was still up, a sinking feeling in his belly making him feel guilty for seeking solitude. He eased the door shut behind him and headed for the kitchen where he knew she would be waiting.

‘You’re late,’ she said, unconfrontationally. ‘Or at least, later than you’ve been for a while.’

‘They finally gave us a new case,’ he told her, trying not to show his excitement and relief at once again being gainfully employed, once again leading the hunt.

‘Oh,’ she responded, not hiding her disappointment.

‘They weren’t going to leave me alone for ever.’ He gave an apologetic shrug.

‘No,’ she agreed. ‘I realize that. It’s just, I was getting used to having you around a bit more than usual, and so were the girls.’

‘We’ve had a good run, perhaps we should just be grateful for that.’

‘Grateful!’ Kate snapped, then immediately softened her tone: ‘You were shot, Sean. I think you earned some time off.’

‘Maybe,’ he answered, desperately wishing he could just be alone as he pulled a glass and a bottle of bourbon from a cupboard the kids couldn’t reach and poured two fingers before emptying his pockets on the kitchen table and slumping into a chair on the other side to his wife.

‘Haven’t seen you do that in a while,’ she told him, her eyes accusing the drink in his hand.

‘I need to sleep tonight and this’ll help.’

‘If I didn’t know better, I’d say you look pretty pleased with yourself,’ she told him.

‘What’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Sitting there, drink in hand, hardly speaking, holier-than-thou look on your face.’ He couldn’t help but grin a little. Maybe she was right. Maybe he was enjoying being back in the same old shit. ‘Yeah, that smile says it all.’

‘Don’t be so pissed off,’ he told her. ‘I’m a detective. They pay me to solve cases, catch the bad guys, save the day, remember?’

‘I’m pissed off because I was worried, Sean. I called you, several times, and left messages, but you didn’t call back – not even a text.’

He lifted his mobile from the table and checked for missed calls. Sure enough she’d called him several times. ‘Sorry,’ he told her. ‘I must have been in the middle of an interview.’

‘I don’t know, Sean – it feels like we’re heading back to the bad old days: me here alone with the kids while you run around trying to get yourself … We can do better than this, can’t we?’

‘It’s only been one night,’ he reminded her.

‘You said it’s a new case, so we all know what that means.’ Sean didn’t respond as a silence fell between them that only increased his yearning to be alone. ‘So what is it?’

‘What’s what?’ he asked unnecessarily.

‘The new case.’

‘A four-year-old boy gone missing from his home in Hampstead,’ he answered, immediately regretting mentioning Hampstead.

‘Hampstead?’ Kate seized on it. ‘Why are you investigating something that happened in Hampstead?’

He took a gulp of the bourbon before answering. ‘They’ve moved us to the Yard.’

‘Why would they do that?’ she asked, her voice heavy with suspicion.

He swallowed the liquid he’d been holding in his mouth and waited for the burning in his throat to cease before answering. ‘They’ve changed my brief,’ he told her. ‘We’re to investigate murders and crimes of special interest across the whole of London, not just the south-east.’

‘Have they centralized all the Murder Teams?’ she asked, her voice tightening with concern.

‘No. Just mine.’

Kate took a few seconds to comprehend what it could mean. ‘So now they can dump anything from anywhere on you? That’s just fucking great, Sean. I mean that’s really just fucking great.’

‘What d’you want me to do?’ he asked. ‘I had no choice.’

‘Don’t be so damn weak,’ she chastised him. ‘You could have said no.’

‘That’s not how it works – you know that.’

‘Sean, it doesn’t work at all. God, it was bad enough before and now it’s going to be even worse, if that’s at all possible. Everything we’ve planned for the next few weeks I might as well just scrap – just chuck it in the bin?’

The frustration at not being alone finally snapped him. ‘I’m sorry if I’m fucking up your social calendar. I thought it was a bit more important to find this four-year-old boy before some paedophile bastard rapes and murders him. I’ll tell his parents I can’t help them any more because my wife’s made dinner reservations – will that make you happy?’

‘Fuck you, Sean, and your self-important, arrogant bullshit. I’m going to bed.’ She sprang to her feet, almost knocking the chair over, then looked across the table accusingly. ‘I don’t suppose there’s much point in asking when you’ll next be home at a reasonable time?’

‘That’s not really up to me, is it? That’s up to whoever took—’

‘I’ve had enough of this crap,’ she told him and turned her back on him as she headed for the stairs. He considered calling after her, trying to make the peace before it was too late, but that would mean more sitting and talking, lessening any chance he’d have of calming his mind enough to think as he needed, to think about who could have taken George Bridgeman. But the damage had already been done and the fight with Kate had only added more turmoil to the mix. Now he wouldn’t be able to think or sleep.

‘Fuck it,’ he swore at the room and drained his glass. ‘Why do I always have to be such a prick?’

4

The only window in the prison cell was made of heavy, opaque, square glass bricks through which the rising sunlight outside struggled to penetrate, but it was enough to stir Mark McKenzie from his shallow sleep. He’d grown used to sleeping in prison cells, at police stations or more permanent institutions. Although he slept better than most, he was still frequently disturbed by the comings and goings of prisoners elsewhere in the custody area – drunken fights and the screams of the mentally ill, locked up until the system decided what to do with them.

He pulled the regulation blue prisoners’ blanket off and padded barefoot on the cold stone floor to the stainless-steel toilet which had been bolted to the wall in a purpose-built alcove of the small room to afford the user some degree of privacy if the cell was being shared. Mercifully he was on his own – the white paper forensic suit ensuring he would not be expected to share this Victorian hole with anyone else. But the suit also marked him out to police and villains alike as something special, and the other criminals had a dog-sense born of the need to survive that told them at a glance that he was no armed robber to be respected and revered; no suspected gangland assassin to be avoided or sucked-up to. No, they knew what he was – a sex case – a rapist or kiddie-fiddler. Either way, he wouldn’t be sharing his accommodation with anyone – just in case. He didn’t fear too much for his safety while he was banged up with the Old Bill – he knew they wouldn’t let the other prisoners near him, and thanks to the advent of CCTV inside custody areas the risk of a visit from a uniformed Neanderthal administering summary justice was unlikely. But if he ended up going back to prison things would be different, even on Rule 43, segregated from the main prison population. He would be constantly living on his nerves, always aware that a vindictive prison officer – or, more likely, a bribed one – might leave a door unlocked just at the right time.

He tried not to dwell on the subject as he finished emptying his bladder and returned to his bed – a flat, blue, plastic mattress on a completely solid wooden bench affixed to the wall on three sides. He pulled the blue blanket back over himself to keep out the morning chill. Clearly some police bastard had turned the heating off in his cell knowing he only had a paper suit and thin blanket to keep out the cold.

As he lay on his back staring at the off-green ceiling his mind wandered back to his life as a young teenager living with his drunken stepfather who beat him for light entertainment and a mother who was too busy with much younger children from her new husband and too in need of the income he provided to do anything about it. And then the stepfather had started making accusations – whispering evil things in his mother’s ear about how he seemed a bit too keen to help bathe the younger children – how he’d caught him sneaking out of their bedrooms in the middle of the night. Even though they couldn’t prove anything, when he was only sixteen years old they had pushed him out of the door with a suitcase and two hundred pounds cash, given to him only once he’d promised never to come back. His pleas to his mother had fallen on deaf ears, but alone in the world he’d survived, living off a pittance of unemployment benefit in godforsaken bedsits until finally he’d been forced to take a job as an apprentice locksmith as part of his Job Seeker programme. After a few months he realized he was actually enjoying the job. Getting up every day knowing he had a purpose. Everybody in the small family business treated him with respect – treated him indeed as if he was part of their family as he watched and learned from the more experienced locksmiths. Soon he could fit almost any type of lock to almost any type of door and had even begun to learn the finer art of picking the locks open – a company speciality that had saved many a customer the expense of fitting new locks to doors that had unexpectedly swung shut on them. It started innocently enough as far as he was concerned – just a bit of harmless thrill-seeking – crouching in the dark at the doors of shops closed for the night, working his fine tools until the locks popped open, pushing the doors inwards until the burglar alarms were activated, then watching from a safe distance as the attending police berated the shopkeeper who they’d dragged out in the middle of the night to turn off the terrible noise, warning them that police would stop responding to their alarms if they couldn’t even be bothered to make sure they’d shut their doors properly. His night-time games were amusing as well as giving him the opportunity to hone his new-found skills, but soon their appeal began to wear thin. He needed more.

The first few years of his life had been happy enough, – as far as he could remember – living with his mother and real father as an only child, but the admiring looks his mother drew from other men drove his father insane with jealousy – an insanity he tried to drown in drink, until finally his alcoholism chased him from the family home never to be seen again. He’d died a few years later and was buried in a pauper’s grave somewhere in the Midlands. After that it had been a succession of strange men he was told to call uncle until such time as they became more permanent in his mother’s life. Some had been decent enough, but most saw him at best as an inconvenience, while a few had treated him as something to be used and abused. All the while he’d had to watch the children of other families being loved and cherished by their parents – knowing that, while he was unwelcome in his own home, they would be sleeping soundly in warm, comfortable beds. If only he could share some of their life.

Finally he could wait no longer and at last he perfected the method of becoming part of another family without anyone ever knowing. He slipped into their houses through silently opened windows and doors, his lock-picking skills improving with each adventure, standing in the kitchens and living rooms of the families as they slept upstairs, knowing that if he was caught he would be accused of terrible things. But all he wanted was to be alone with them, safe and accepted – part of a real family.

For a long time he was too afraid to venture upstairs and stand in the same rooms as the sleeping children. Instead he’d settled for taking things to remind him of his innocent visits; not things of value, just little keepsakes no one would miss. But eventually that was no longer enough, and his fear of walking up the long, creaking staircases was overwhelmed by his need to see the sleeping children. So he took his first terrifying walk up the stairs, struggling to control his bladder and bowels as he slid past the parents’ room and entered the room of a little girl bathed in her blue night-light.

It had been everything he’d dreamed it would be – standing, watching her little chest rise and fall under the covers, her long curly hair draped over her face like a beautiful veil. Her room was warm and pretty, with princesses and rainbows on her wallpaper, toys and dolls on every surface as she slept in her soft, comfortable bed, wrapped in a floral-patterned duvet that smelled of fresh orchids on a spring day. So this was how the other children had lived – cared for and adored, as far from his own childhood as it was possible to imagine. Tears had rolled down his face as he’d stood watching her – tears of happiness for her and sadness for his own lost childhood. After what seemed an age he left her room and slipped away as quietly as he’d arrived, taking one of her dolls from the shelf as he did so – being sure to lock the window behind him, leaving it just as he found it.

Time and again he paid his visits to the sleeping, always taking something small and personal from the child’s room – just another toy lost or misplaced, soon forgotten by both parents and child alike. His collection of soft toys and dolls was squeezed into a suitcase stored under his bed for when he needed their help to relive his innocent little visits.

But his wage as an apprentice remained small and while he was in the houses he saw many things of value: watches, jewellery, cash in purses and wallets. Small things at first, but as he became bolder the things he took grew larger: laptops, iPads, Blu-ray players. He knew just the landlord in just the pub to sell them to – no questions asked, cash over the counter. Finally his luck ran out as he let himself out of the back door of a semi-detached in Tufnell Park, straight into the arms of a waiting uniform police constable who was quietly investigating a call from a concerned neighbour who thought they’d heard something suspicious in next-door’s garden. Obviously he’d been unable to explain the laptop and iPhone they’d found in his bag and once it was established he was not the lawful occupier of the semi-detached he was arrested for residential burglary and handed over to the local CID for further investigation.

He could still clearly remember the abject terror he’d felt when the detectives had handcuffed him and said they were going to take him back to his bedsit to search it for further stolen goods – his mind suddenly unable to think of anything other than the suitcase under the bed and the damning evidence it contained. Trying not to sound too desperate, he told the police he’d happily admit to the burglary and that therefore there was really no need to search his home. But his pleas had been ignored.