Полная версия

Полная версияAn Essay Upon Projects

Words, and even usages in style, may be altered by custom, and proprieties in speech differ according to the several dialects of the country, and according to the different manner in which several languages do severally express themselves.

But there is a direct signification of words, or a cadence in expression, which we call speaking sense; this, like truth, is sullen and the same, ever was and will be so, in what manner, and in what language soever it is expressed. Words without it are only noise, which any brute can make as well as we, and birds much better; for words without sense make but dull music. Thus a man may speak in words, but perfectly unintelligible as to meaning; he may talk a great deal, but say nothing. But it is the proper position of words, adapted to their significations, which makes them intelligible, and conveys the meaning of the speaker to the understanding of the hearer; the contrary to which we call nonsense; and there is a superfluous crowding in of insignificant words, more than are needful to express the thing intended, and this is impertinence; and that again, carried to an extreme, is ridiculous.

Thus when our discourse is interlined with needless oaths, curses, and long parentheses of imprecations, and with some of very indirect signification, they become very impertinent; and these being run to the extravagant degree instanced in before, become perfectly ridiculous and nonsense, and without forming it into an argument, it appears to be nonsense by the contradictoriness; and it appears impertinent by the insignificancy of the expression.

After all, how little it becomes a gentleman to debauch his mouth with foul language, I refer to themselves in a few particulars.

This vicious custom has prevailed upon good manners too far; but yet there are some degrees to which it has not yet arrived.

As, first, the worst slaves to this folly will neither teach it to nor approve of it in their children. Some of the most careless will indeed negatively teach it by not reproving them for it; but sure no man ever ordered his children to be taught to curse or swear.

2. The grace of swearing has not obtained to be a mode yet among the women: “God damn ye” does not fit well upon a female tongue; it seems to be a masculine vice, which the women are not arrived to yet; and I would only desire those gentlemen who practice it themselves to hear a woman swear: it has no music at all there, I am sure; and just as little does it become any gentleman, if he would suffer himself to be judged by all the laws of sense or good manners in the world.

It is a senseless, foolish, ridiculous practice; it is a mean to no manner of end; it is words spoken which signify nothing; it is folly acted for the sake of folly, which is a thing even the devil himself don’t practice. The devil does evil, we say, but it is for some design, either to seduce others, or, as some divines say, from a principle of enmity to his Maker. Men steal for gain, and murder to gratify their avarice or revenge; whoredoms and ravishments, adulteries and sodomy, are committed to please a vicious appetite, and have always alluring objects; and generally all vices have some previous cause, and some visible tendency. But this, of all vicious practices, seems the most nonsensical and ridiculous; there is neither pleasure nor profit, no design pursued, no lust gratified, but is a mere frenzy of the tongue, a vomit of the brain, which works by putting a contrary upon the course of nature.

Again, other vices men find some reason or other to give for, or excuses to palliate. Men plead want to extenuate theft, and strong provocations to excuse murders, and many a lame excuse they will bring for whoring; but this sordid habit even those that practise it will own to be a crime, and make no excuse for it; and the most I could ever hear a man say for it was that he could not help it.

Besides, as it is an inexcusable impertinence, so it is a breach upon good manners and conversation, for a man to impose the clamour of his oaths upon the company he converses with; if there be any one person in the company that does not approve the way, it is an imposing upon him with a freedom beyond civility.

To suppress this, laws, Acts of Parliament, and proclamations are baubles and banters, the laughter of the lewd party, and never had, as I could perceive, any influence upon the practice; nor are any of our magistrates fond or forward of putting them in execution.

It must be example, not penalties, must sink this crime; and if the gentlemen of England would once drop it as a mode, the vice is so foolish and ridiculous in itself, it would soon grow odious and out of fashion.

This work such an academy might begin, and I believe nothing would so soon explode the practice as the public discouragement of it by such a society; where all our customs and habits, both in speech and behaviour, should receive an authority. All the disputes about precedency of wit, with the manners, customs, and usages of the theatre, would be decided here; plays should pass here before they were acted, and the critics might give their censures and damn at their pleasure; nothing would ever die which once received life at this original. The two theatres might end their jangle, and dispute for priority no more; wit and real worth should decide the controversy, and here should be the infallible judge.

The strife would then be only to do well,And he alone be crowned who did excel.Ye call them Whigs, who from the church withdrew,But now we have our stage dissenters too,Who scruple ceremonies of pit and box,And very few are sound and orthodox,But love disorder so, and are so nice,They hate conformity, though ’tis in vice.Some are for patent hierarchy; and some,Like the old Gauls, seek out for elbow room;Their arbitrary governors disown,And build a conventicle stage of their own.Fanatic beaux make up the gaudy show,And wit alone appears incognito.Wit and religion suffer equal fate;Neglect of both attends the warm debate.For while the parties strive and countermine,Wit will as well as piety decline.Next to this, which I esteem as the most noble and most useful proposal in this book, I proceed to academies for military studies, and because I design rather to express my meaning than make a large book, I bring them all into one chapter.

I allow the war is the best academy in the world, where men study by necessity and practice by force, and both to some purpose, with duty in the action, and a reward in the end; and it is evident to any man who knows the world, or has made any observations on things, what an improvement the English nation has made during this seven years’ war.

But should you ask how clear it first cost, and what a condition England was in for a war at first on this account – how almost all our engineers and great officers were foreigners, it may put us in mind how necessary it is to have our people so practised in the arts of war that they may not be novices when they come to the experiment.

I have heard some who were no great friends to the Government take advantage to reflect upon the king, in the beginning of his wars in Ireland, that he did not care to trust the English, but all his great officers, his generals, and engineers were foreigners. And though the case was so plain as to need no answer, and the persons such as deserved none, yet this must be observed, though it was very strange: that when the present king took possession of this kingdom, and, seeing himself entering upon the bloodiest war this age has known, began to regulate his army, he found but very few among the whole martial part of the nation fit to make use of for general officers, and was forced to employ strangers, and make them Englishmen (as the Counts Schomberg, Ginkel, Solms, Ruvigny, and others); and yet it is to be observed also that all the encouragement imaginable was given to the English gentlemen to qualify themselves, by giving no less than sixteen regiments to gentlemen of good families who had never been in any service and knew but very little how to command them. Of these, several are now in the army, and have the rewards suitable to their merit, being major-generals, brigadiers, and the like.

If, then, a long peace had so reduced us to a degree of ignorance that might have been dangerous to us, had we not a king who is always followed by the greatest masters in the world, who knows what peace and different governors may bring us to again?

The manner of making war differs perhaps as much as anything in the world; and if we look no further back than our civil wars, it is plain a general then would hardly be fit to be a colonel now, saving his capacity of improvement. The defensive art always follows the offensive; and though the latter has extremely got the start of the former in this age, yet the other is mightily improving also.

We saw in England a bloody civil war, where, according to the old temper of the English, fighting was the business. To have an army lying in such a post as not to be able to come at them was a thing never heard of in that war; even the weakest party would always come out and fight (Dunbar fight, for instance); and they that were beaten to-day would fight again to-morrow, and seek one another out with such eagerness, as if they had been in haste to have their brains knocked out. Encampments, intrenchments, batteries, counter-marchings, fortifying of camps, and cannonadings were strange and almost unknown things; and whole campaigns were passed over, and hardly any tents made use of. Battles, surprises, storming of towns, skirmishes, sieges, ambuscades, and beating up quarters was the news of every day. Now it is frequent to have armies of fifty thousand men of a side stand at bay within view of one another, and spend a whole campaign in dodging (or, as it is genteelly called, observing) one another, and then march off into winter quarters. The difference is in the maxims of war, which now differ as much from what they were formerly as long perukes do from piqued beards, or as the habits of the people do now from what they then were. The present maxims of the war are:

“Never fight without a manifest advantage.”

“And always encamp so as not to be forced to it.”

And if two opposite generals nicely observe both these rules, it is impossible they should ever come to fight.

I grant that this way of making war spends generally more money and less blood than former wars did; but then it spins wars out to a greater length; and I almost question whether, if this had been the way of fighting of old, our civil war had not lasted till this day. Their maxim was:

“Wherever you meet your enemy, fight him.”

But the case is quite different now; and I think it is plain in the present war that it is not he who has the longest sword, so much as he who has the longest purse, will hold the war out best. Europe is all engaged in the war, and the men will never be exhausted while either party can find money; but he who finds himself poorest must give out first; and this is evident in the French king, who now inclines to peace, and owns it, while at the same time his armies are numerous and whole. But the sinews fail; he finds his exchequer fail, his kingdom drained, and money hard to come at: not that I believe half the reports we have had of the misery and poverty of the French are true; but it is manifest the King of France finds, whatever his armies may do, his money won’t hold out so long as the Confederates, and therefore he uses all the means possible to procure a peace, while he may do it with the most advantage.

There is no question but the French may hold the war out several years longer; but their king is too wise to let things run to extremity. He will rather condescend to peace upon hard terms now than stay longer, if he finds himself in danger to be forced to worse.

This being the only digression I design to be guilty of, I hope I shall be excused it.

The sum of all is this: that, since it is so necessary to be in a condition for war in a time of peace, our people should be inured to it. It is strange that everything should be ready but the soldier: ships are ready, and our trade keeps the seamen always taught, and breeds up more; but soldiers, horsemen, engineers, gunners, and the like must be bred and taught; men are not born with muskets on their shoulders, nor fortifications in their heads; it is not natural to shoot bombs and undermine towns: for which purpose I propose a

Royal Academy for Military ExercisesThe founder the king himself; the charge to be paid by the public, and settled by a revenue from the Crown, to be paid yearly.

I propose this to consist of four parts:

1. A college for breeding up of artists in the useful practice of all military exercises; the scholars to be taken in young, and be maintained, and afterwards under the king’s care for preferment, as their merit and His Majesty’s favour shall recommend them; from whence His Majesty would at all times be furnished with able engineers, gunners, fire-masters. bombardiers, miners, and the like.

The second college for voluntary students in the same exercises; who should all upon certain limited conditions be entertained, and have all the advantages of the lectures, experiments, and learning of the college, and be also capable of several titles, profits, and settlements in the said college, answerable to the Fellows in the Universities.

The third college for temporary study, into which any person who is a gentleman and an Englishman, entering his name and conforming to the orders of the house, shall be entertained like a gentleman for one whole year gratis, and taught by masters appointed out of the second college.

The fourth college, of schools only, where all persons whatsoever for a small allowance shall be taught and entered in all the particular exercises they desire; and this to be supplied by the proficients of the first college.

I could lay out the dimensions and necessary incidents of all this work, but since the method of such a foundation is easy and regular from the model of other colleges, I shall only state the economy of the house.

The building must be very large, and should rather be stately and magnificent in figure than gay and costly in ornament: and I think such a house as Chelsea College, only about four times as big, would answer it; and yet, I believe, might be finished for as little charge as has been laid out in that palace-like hospital.

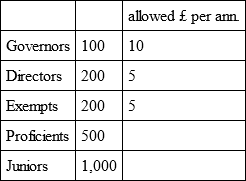

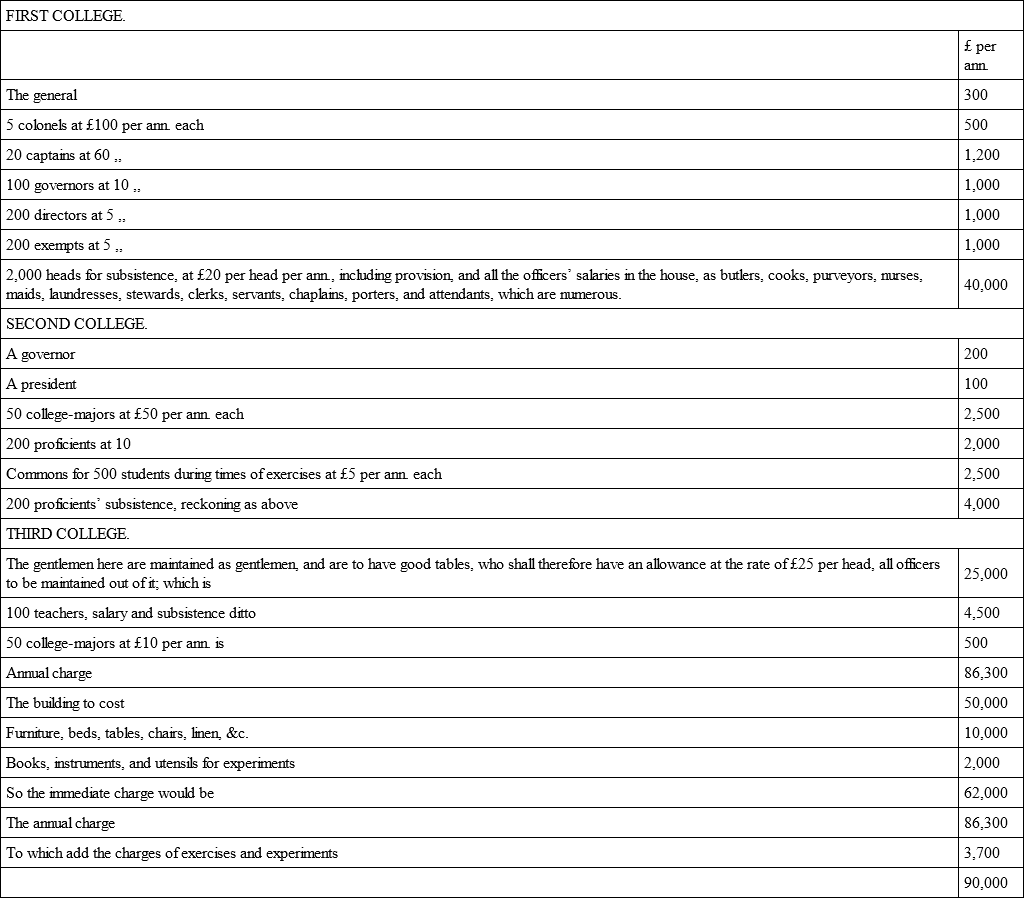

The first college should consist of one general, five colonels, twenty captains.

Being such as graduates by preferment, at first named by the founder; and after the first settlement to be chosen out of the first or second colleges; with apartments in the college, and salaries.

2,000 scholars, among whom shall be the following degrees:

The general to be named by the founder, out of the colonels; the colonels to be named by the general, out of the captains; the captains out of the governors; the governors from the directors; and the directors from the exempts; and so on.

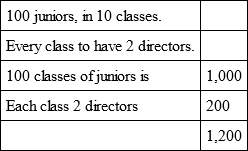

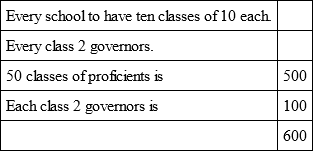

The juniors to be divided into ten schools; the schools to be thus governed: every school has

The proficients to be divided into five schools:

The exempts to be supernumerary, having a small allowance, and maintained in the college till preferment offer.

The second college to consist of voluntary students, to be taken in, after a certain degree of learning, from among the proficients of the first, or from any other schools, after such and such limitations of learning; who study at their own charge, being allowed certain privileges; as —

Chambers rent-free on condition of residence.

Commons gratis, for certain fixed terms.

Preferment, on condition of a term of years’ residence.

Use of libraries, instruments, and lectures of the college.

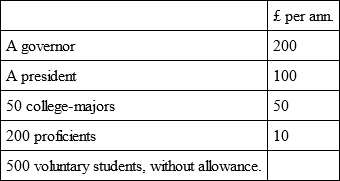

This college should have the following preferments, with salaries

The third and fourth colleges, consisting only of schools for temporary study, may be thus:

The third – being for gentlemen to learn the necessary arts and exercises to qualify them for the service of their country, and entertaining them one whole year at the public charge – may be supposed to have always one thousand persons on its hands, and cannot have less than 100 teachers, whom I would thus order:

Every teacher shall continue at least one year, but by allowance two years at most; shall have £20 per annum extraordinary allowance; shall be bound to give their constant attendance; and shall have always five college-majors of the second college to supervise them, who shall command a month, and then be succeeded by five others, and, so on – £10 per annum extraordinary to be paid them for their attendance.

The gentlemen who practise to be put to no manner of charge, but to be obliged strictly to the following articles:

1. To constant residence, not to lie out of the house without leave of the college-major.

2. To perform all the college exercises, as appointed by the masters, without dispute.

3. To submit to the orders of the house.

To quarrel or give ill-language should be a crime to be punished by way of fine only, the college-major to be judge, and the offender be put into custody till he ask pardon of the person wronged; by which means every gentleman who has been affronted has sufficient satisfaction.

But to strike challenge, draw, or fight, should be more severely punished; the offender to be declared no gentleman, his name posted up at the college-gate, his person expelled the house, and to be pumped as a rake if ever he is taken within the college-walls.

The teachers of this college to be chosen, one half out of the exempts of the first college, and the other out of the proficients of the second.

The fourth college, being only of schools, will be neither chargeable nor troublesome, but may consist of as many as shall offer themselves to be taught, and supplied with teachers from the other schools.

The proposal, being of so large an extent, must have a proportionable settlement for its maintenance; and the benefit being to the whole kingdom, the charge will naturally lie upon the public, and cannot well be less, considering the number of persons to be maintained, than as follows.

The king’s magazines to furnish them with 500 barrels of gunpowder per annum for the public uses of exercises and experiments.

In the first of these colleges should remain the governing part, and all the preferments to be made from thence, to be supplied in course from the other; the general of the first to give orders to the other, and be subject only to the founder.

The government should be all military, with a constitution for the same regulated for that purpose, and a council to hear and determine the differences and trespasses by the college laws.

The public exercises likewise military, and all the schools be disciplined under proper officers, who are so in turn or by order of the general, and continue but for the day.

The several classes to perform several studies, and but one study to a distinct class, and the persons, as they remove from one study to another, to change their classes, but so as that in the general exercises all the scholars may be qualified to act all the several parts as they may be ordered.

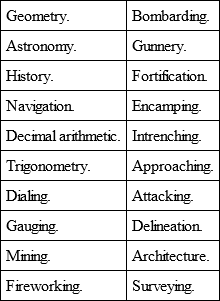

The proper studies of this college should be the following:

And all arts or sciences appendices to such as these, with exercises for the body, to which all should be obliged, as their genius and capacities led them, as:

1. Swimming; which no soldier, and, indeed, no man whatever, ought to be without.

2. Handling all sorts of firearms.

3. Marching and counter-marching in form.

4. Fencing and the long-staff.

5. Riding and managing, or horsemanship.

6. Running, leaping, and wrestling.

And herewith should also be preserved and carefully taught all the customs, usages, terms of war, and terms of art used in sieges, marches of armies and encampments, that so a gentleman taught in this college should be no novice when he comes into the king’s armies, though he has seen no service abroad. I remember the story of an English gentleman, an officer at the siege of Limerick, in Ireland, who, though he was brave enough upon action, yet for the only matter of being ignorant in the terms of art, and knowing not how to talk camp language, was exposed to be laughed at by the whole army for mistaking the opening of the trenches, which he thought had been a mine against the town.

The experiments of these colleges would be as well worth publishing as the acts of the Royal Society. To which purpose the house must be built where they may have ground to cast bombs, to raise regular works, as batteries, bastions, half-moons, redoubts, horn-works, forts, and the like; with the convenience of water to draw round such works, to exercise the engineers in all the necessary experiments of draining and mining under ditches. There must be room to fire great shot at a distance, to cannonade a camp, to throw all sorts of fireworks and machines that are, or shall be, invented; to open trenches, form camps, &c.

Their public exercises will be also very diverting, and more worth while for any gentleman to see than the sights or shows which our people in England are so fond of.

I believe as a constitution might be formed from these generals, this would be the greatest, the gallantest and the most useful foundation in the world. The English gentry would be the best qualified, and consequently best accepted abroad, and most useful at home of any people in the world; and His Majesty should never more be exposed to the necessity of employing foreigners in the posts of trust and service in his armies.

And that the whole kingdom might in some degree be better qualified for service, I think the following project would be very useful:

When our military weapon was the long-bow, at which our English nation in some measure excelled the whole world, the meanest countryman was a good archer; and that which qualified them so much for service in the war was their diversion in times of peace, which also had this good effect – that when an army was to be raised they needed no disciplining: and for the encouragement of the people to an exercise so publicly profitable an Act of Parliament was made to oblige every parish to maintain butts for the youth in the country to shoot at.

Since our way of fighting is now altered, and this destructive engine the musket is the proper arms for the soldier, I could wish the diversion also of the English would change too, that our pleasures and profit might correspond. It is a great hindrance to this nation, especially where standing armies are a grievance, that if ever a war commence, men must have at least a year before they are thought fit to face an enemy, to instruct them how to handle their arms; and new-raised men are called raw soldiers. To help this – at least, in some, measure – I would propose that the public exercises of our youth should by some public encouragement (for penalties won’t do it) be drawn off from the foolish boyish sports of cocking and cricketing, and from tippling, to shooting with a firelock (an exercise as pleasant as it is manly and generous) and swimming, which is a thing so many ways profitable, besides its being a great preservative of health, that methinks no man ought to be without it.

1. For shooting, the colleges I have mentioned above, having provided for the instructing the gentry at the king’s charge, that the gentry, in return of a favour, should introduce it among the country people, which might easily be done thus: