Полная версия

Полная версияПолная версия:

A Journal of the Plague Year

As to the suddenness of people's dying at this time, more than before, there were innumerable instances of it, and I could name several in my neighbourhood. One family without the Bars, and not far from me, were all seemingly well on the Monday, being ten in family. That evening one maid and one apprentice were taken ill and died the next morning – when the other apprentice and two children were touched, whereof one died the same evening, and the other two on Wednesday. In a word, by Saturday at noon the master, mistress, four children, and four servants were all gone, and the house left entirely empty, except an ancient woman who came in to take charge of the goods for the master of the family's brother, who lived not far off, and who had not been sick.

Many houses were then left desolate, all the people being carried away dead, and especially in an alley farther on the same side beyond the Bars, going in at the sign of Moses and Aaron, there were several houses together which, they said, had not one person left alive in them; and some that died last in several of those houses were left a little too long before they were fetched out to be buried; the reason of which was not, as some have written very untruly, that the living were not sufficient to bury the dead, but that the mortality was so great in the yard or alley that there was nobody left to give notice to the buriers or sextons that there were any dead bodies there to be buried. It was said, how true I know not, that some of those bodies were so much corrupted and so rotten that it was with difficulty they were carried; and as the carts could not come any nearer than to the Alley Gate in the High Street, it was so much the more difficult to bring them along; but I am not certain how many bodies were then left. I am sure that ordinarily it was not so.

As I have mentioned how the people were brought into a condition to despair of life and abandon themselves, so this very thing had a strange effect among us for three or four weeks; that is, it made them bold and venturous: they were no more shy of one another, or restrained within doors, but went anywhere and everywhere, and began to converse. One would say to another, 'I do not ask you how you are, or say how I am; it is certain we shall all go; so 'tis no matter who is all sick or who is sound'; and so they ran desperately into any place or any company.

As it brought the people into public company, so it was surprising how it brought them to crowd into the churches. They inquired no more into whom they sat near to or far from, what offensive smells they met with, or what condition the people seemed to be in; but, looking upon themselves all as so many dead corpses, they came to the churches without the least caution, and crowded together as if their lives were of no consequence compared to the work which they came about there. Indeed, the zeal which they showed in coming, and the earnestness and affection they showed in their attention to what they heard, made it manifest what a value people would all put upon the worship of God if they thought every day they attended at the church that it would be their last.

Nor was it without other strange effects, for it took away, all manner of prejudice at or scruple about the person whom they found in the pulpit when they came to the churches. It cannot be doubted but that many of the ministers of the parish churches were cut off, among others, in so common and dreadful a calamity; and others had not courage enough to stand it, but removed into the country as they found means for escape. As then some parish churches were quite vacant and forsaken, the people made no scruple of desiring such Dissenters as had been a few years before deprived of their livings by virtue of the Act of Parliament called the Act of Uniformity to preach in the churches; nor did the church ministers in that case make any difficulty of accepting their assistance; so that many of those whom they called silenced ministers had their mouths opened on this occasion and preached publicly to the people.

Here we may observe and I hope it will not be amiss to take notice of it that a near view of death would soon reconcile men of good principles one to another, and that it is chiefly owing to our easy situation in life and our putting these things far from us that our breaches are fomented, ill blood continued, prejudices, breach of charity and of Christian union, so much kept and so far carried on among us as it is. Another plague year would reconcile all these differences; a close conversing with death, or with diseases that threaten death, would scum off the gall from our tempers, remove the animosities among us, and bring us to see with differing eyes than those which we looked on things with before. As the people who had been used to join with the Church were reconciled at this time with the admitting the Dissenters to preach to them, so the Dissenters, who with an uncommon prejudice had broken off from the communion of the Church of England, were now content to come to their parish churches and to conform to the worship which they did not approve of before; but as the terror of the infection abated, those things all returned again to their less desirable channel and to the course they were in before.

I mention this but historically. I have no mind to enter into arguments to move either or both sides to a more charitable compliance one with another. I do not see that it is probable such a discourse would be either suitable or successful; the breaches seem rather to widen, and tend to a widening further, than to closing, and who am I that I should think myself able to influence either one side or other? But this I may repeat again, that 'tis evident death will reconcile us all; on the other side the grave we shall be all brethren again. In heaven, whither I hope we may come from all parties and persuasions, we shall find neither prejudice or scruple; there we shall be of one principle and of one opinion. Why we cannot be content to go hand in hand to the Place where we shall join heart and hand without the least hesitation, and with the most complete harmony and affection – I say, why we cannot do so here I can say nothing to, neither shall I say anything more of it but that it remains to be lamented.

I could dwell a great while upon the calamities of this dreadful time, and go on to describe the objects that appeared among us every day, the dreadful extravagancies which the distraction of sick people drove them into; how the streets began now to be fuller of frightful objects, and families to be made even a terror to themselves. But after I have told you, as I have above, that one man, being tied in his bed, and finding no other way to deliver himself, set the bed on fire with his candle, which unhappily stood within his reach, and burnt himself in his bed; and how another, by the insufferable torment he bore, danced and sung naked in the streets, not knowing one ecstasy from another; I say, after I have mentioned these things, what can be added more? What can be said to represent the misery of these times more lively to the reader, or to give him a more perfect idea of a complicated distress?

I must acknowledge that this time was terrible, that I was sometimes at the end of all my resolutions, and that I had not the courage that I had at the beginning. As the extremity brought other people abroad, it drove me home, and except having made my voyage down to Blackwall and Greenwich, as I have related, which was an excursion, I kept afterwards very much within doors, as I had for about a fortnight before. I have said already that I repented several times that I had ventured to stay in town, and had not gone away with my brother and his family, but it was too late for that now; and after I had retreated and stayed within doors a good while before my impatience led me abroad, then they called me, as I have said, to an ugly and dangerous office which brought me out again; but as that was expired while the height of the distemper lasted, I retired again, and continued close ten or twelve days more, during which many dismal spectacles represented themselves in my view out of my own windows and in our own street – as that particularly from Harrow Alley, of the poor outrageous creature which danced and sung in his agony; and many others there were. Scarce a day or night passed over but some dismal thing or other happened at the end of that Harrow Alley, which was a place full of poor people, most of them belonging to the butchers or to employments depending upon the butchery.

Sometimes heaps and throngs of people would burst out of the alley, most of them women, making a dreadful clamour, mixed or compounded of screeches, cryings, and calling one another, that we could not conceive what to make of it. Almost all the dead part of the night the dead-cart stood at the end of that alley, for if it went in it could not well turn again, and could go in but a little way. There, I say, it stood to receive dead bodies, and as the churchyard was but a little way off, if it went away full it would soon be back again. It is impossible to describe the most horrible cries and noise the poor people would make at their bringing the dead bodies of their children and friends out of the cart, and by the number one would have thought there had been none left behind, or that there were people enough for a small city living in those places. Several times they cried 'Murder', sometimes 'Fire'; but it was easy to perceive it was all distraction, and the complaints of distressed and distempered people.

I believe it was everywhere thus as that time, for the plague raged for six or seven weeks beyond all that I have expressed, and came even to such a height that, in the extremity, they began to break into that excellent order of which I have spoken so much in behalf of the magistrates; namely, that no dead bodies were seen in the street or burials in the daytime: for there was a necessity in this extremity to bear with its being otherwise for a little while.

One thing I cannot omit here, and indeed I thought it was extraordinary, at least it seemed a remarkable hand of Divine justice: viz., that all the predictors, astrologers, fortune-tellers, and what they called cunning-men, conjurers, and the like: calculators of nativities and dreamers of dream, and such people, were gone and vanished; not one of them was to be found. I am verily persuaded that a great number of them fell in the heat of the calamity, having ventured to stay upon the prospect of getting great estates; and indeed their gain was but too great for a time, through the madness and folly of the people. But now they were silent; many of them went to their long home, not able to foretell their own fate or to calculate their own nativities. Some have been critical enough to say that every one of them died. I dare not affirm that; but this I must own, that I never heard of one of them that ever appeared after the calamity was over.

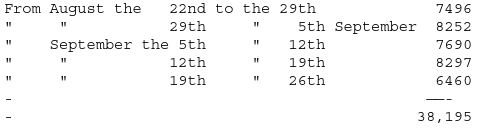

But to return to my particular observations during this dreadful part of the visitation. I am now come, as I have said, to the month of September, which was the most dreadful of its kind, I believe, that ever London saw; for, by all the accounts which I have seen of the preceding visitations which have been in London, nothing has been like it, the number in the weekly bill amounting to almost 40,000 from the 22nd of August to the 26th of September, being but five weeks. The particulars of the bills are as follows, viz.: —

This was a prodigious number of itself, but if I should add the reasons which I have to believe that this account was deficient, and how deficient it was, you would, with me, make no scruple to believe that there died above ten thousand a week for all those weeks, one week with another, and a proportion for several weeks both before and after. The confusion among the people, especially within the city, at that time, was inexpressible. The terror was so great at last that the courage of the people appointed to carry away the dead began to fail them; nay, several of them died, although they had the distemper before and were recovered, and some of them dropped down when they have been carrying the bodies even at the pit side, and just ready to throw them in; and this confusion was greater in the city because they had flattered themselves with hopes of escaping, and thought the bitterness of death was past. One cart, they told us, going up Shoreditch was forsaken of the drivers, or being left to one man to drive, he died in the street; and the horses going on overthrew the cart, and left the bodies, some thrown out here, some there, in a dismal manner. Another cart was, it seems, found in the great pit in Finsbury Fields, the driver being dead, or having been gone and abandoned it, and the horses running too near it, the cart fell in and drew the horses in also. It was suggested that the driver was thrown in with it and that the cart fell upon him, by reason his whip was seen to be in the pit among the bodies; but that, I suppose, could not be certain.

In our parish of Aldgate the dead-carts were several times, as I have heard, found standing at the churchyard gate full of dead bodies, but neither bellman or driver or any one else with it; neither in these or many other cases did they know what bodies they had in their cart, for sometimes they were let down with ropes out of balconies and out of windows, and sometimes the bearers brought them to the cart, sometimes other people; nor, as the men themselves said, did they trouble themselves to keep any account of the numbers.

The vigilance of the magistrates was now put to the utmost trial – and, it must be confessed, can never be enough acknowledged on this occasion also; whatever expense or trouble they were at, two things were never neglected in the city or suburbs either: —

(1) Provisions were always to be had in full plenty, and the price not much raised neither, hardly worth speaking.

(2) No dead bodies lay unburied or uncovered; and if one walked from one end of the city to another, no funeral or sign of it was to be seen in the daytime, except a little, as I have said above, in the three first weeks in September.

This last article perhaps will hardly be believed when some accounts which others have published since that shall be seen, wherein they say that the dead lay unburied, which I am assured was utterly false; at least, if it had been anywhere so, it must have been in houses where the living were gone from the dead (having found means, as I have observed, to escape) and where no notice was given to the officers. All which amounts to nothing at all in the case in hand; for this I am positive in, having myself been employed a little in the direction of that part in the parish in which I lived, and where as great a desolation was made in proportion to the number of inhabitants as was anywhere; I say, I am sure that there were no dead bodies remained unburied; that is to say, none that the proper officers knew of; none for want of people to carry them off, and buriers to put them into the ground and cover them; and this is sufficient to the argument; for what might lie in houses and holes, as in Moses and Aaron Alley, is nothing; for it is most certain they were buried as soon as they were found. As to the first article (namely, of provisions, the scarcity or dearness), though I have mentioned it before and shall speak of it again, yet I must observe here: —

(1) The price of bread in particular was not much raised; for in the beginning of the year, viz., in the first week in March, the penny wheaten loaf was ten ounces and a half; and in the height of the contagion it was to be had at nine ounces and a half, and never dearer, no, not all that season. And about the beginning of November it was sold ten ounces and a half again; the like of which, I believe, was never heard of in any city, under so dreadful a visitation, before.

(2) Neither was there (which I wondered much at) any want of bakers or ovens kept open to supply the people with the bread; but this was indeed alleged by some families, viz., that their maidservants, going to the bakehouses with their dough to be baked, which was then the custom, sometimes came home with the sickness (that is to say the plague) upon them.

In all this dreadful visitation there were, as I have said before, but two pest-houses made use of, viz., one in the fields beyond Old Street and one in Westminster; neither was there any compulsion used in carrying people thither. Indeed there was no need of compulsion in the case, for there were thousands of poor distressed people who, having no help or conveniences or supplies but of charity, would have been very glad to have been carried thither and been taken care of; which, indeed, was the only thing that I think was wanting in the whole public management of the city, seeing nobody was here allowed to be brought to the pest-house but where money was given, or security for money, either at their introducing or upon their being cured and sent out – for very many were sent out again whole; and very good physicians were appointed to those places, so that many people did very well there, of which I shall make mention again. The principal sort of people sent thither were, as I have said, servants who got the distemper by going on errands to fetch necessaries to the families where they lived, and who in that case, if they came home sick, were removed to preserve the rest of the house; and they were so well looked after there in all the time of the visitation that there was but 156 buried in all at the London pest-house, and 159 at that of Westminster.

By having more pest-houses I am far from meaning a forcing all people into such places. Had the shutting up of houses been omitted and the sick hurried out of their dwellings to pest-houses, as some proposed, it seems, at that time as well as since, it would certainly have been much worse than it was. The very removing the sick would have been a spreading of the infection, and rather because that removing could not effectually clear the house where the sick person was of the distemper; and the rest of the family, being then left at liberty, would certainly spread it among others.

The methods also in private families, which would have been universally used to have concealed the distemper and to have concealed the persons being sick, would have been such that the distemper would sometimes have seized a whole family before any visitors or examiners could have known of it. On the other hand, the prodigious numbers which would have been sick at a time would have exceeded all the capacity of public pest-houses to receive them, or of public officers to discover and remove them.

This was well considered in those days, and I have heard them talk of it often. The magistrates had enough to do to bring people to submit to having their houses shut up, and many ways they deceived the watchmen and got out, as I have observed. But that difficulty made it apparent that they would have found it impracticable to have gone the other way to work, for they could never have forced the sick people out of their beds and out of their dwellings. It must not have been my Lord Mayor's officers, but an army of officers, that must have attempted it; and the people, on the other hand, would have been enraged and desperate, and would have killed those that should have offered to have meddled with them or with their children and relations, whatever had befallen them for it; so that they would have made the people, who, as it was, were in the most terrible distraction imaginable, I say, they would have made them stark mad; whereas the magistrates found it proper on several accounts to treat them with lenity and compassion, and not with violence and terror, such as dragging the sick out of their houses or obliging them to remove themselves, would have been.

This leads me again to mention the time when the plague first began; that is to say, when it became certain that it would spread over the whole town, when, as I have said, the better sort of people first took the alarm and began to hurry themselves out of town. It was true, as I observed in its place, that the throng was so great, and the coaches, horses, waggons, and carts were so many, driving and dragging the people away, that it looked as if all the city was running away; and had any regulations been published that had been terrifying at that time, especially such as would pretend to dispose of the people otherwise than they would dispose of themselves, it would have put both the city and suburbs into the utmost confusion.

But the magistrates wisely caused the people to be encouraged, made very good bye-laws for the regulating the citizens, keeping good order in the streets, and making everything as eligible as possible to all sorts of people.

In the first place, the Lord Mayor and the sheriffs, the Court of Aldermen, and a certain number of the Common Council men, or their deputies, came to a resolution and published it, viz., that they would not quit the city themselves, but that they would be always at hand for the preserving good order in every place and for the doing justice on all occasions; as also for the distributing the public charity to the poor; and, in a word, for the doing the duty and discharging the trust reposed in them by the citizens to the utmost of their power.

In pursuance of these orders, the Lord Mayor, sheriffs, &c., held councils every day, more or less, for making such dispositions as they found needful for preserving the civil peace; and though they used the people with all possible gentleness and clemency, yet all manner of presumptuous rogues such as thieves, housebreakers, plunderers of the dead or of the sick, were duly punished, and several declarations were continually published by the Lord Mayor and Court of Aldermen against such.

Also all constables and churchwardens were enjoined to stay in the city upon severe penalties, or to depute such able and sufficient housekeepers as the deputy aldermen or Common Council men of the precinct should approve, and for whom they should give security; and also security in case of mortality that they would forthwith constitute other constables in their stead.

These things re-established the minds of the people very much, especially in the first of their fright, when they talked of making so universal a flight that the city would have been in danger of being entirely deserted of its inhabitants except the poor, and the country of being plundered and laid waste by the multitude. Nor were the magistrates deficient in performing their part as boldly as they promised it; for my Lord Mayor and the sheriffs were continually in the streets and at places of the greatest danger, and though they did not care for having too great a resort of people crowding about them, yet in emergent cases they never denied the people access to them, and heard with patience all their grievances and complaints. My Lord Mayor had a low gallery built on purpose in his hall, where he stood a little removed from the crowd when any complaint came to be heard, that he might appear with as much safety as possible.

Likewise the proper officers, called my Lord Mayor's officers, constantly attended in their turns, as they were in waiting; and if any of them were sick or infected, as some of them were, others were instantly employed to fill up and officiate in their places till it was known whether the other should live or die.

In like manner the sheriffs and aldermen did in their several stations and wards, where they were placed by office, and the sheriff's officers or sergeants were appointed to receive orders from the respective aldermen in their turn, so that justice was executed in all cases without interruption. In the next place, it was one of their particular cares to see the orders for the freedom of the markets observed, and in this part either the Lord Mayor or one or both of the sheriffs were every market-day on horseback to see their orders executed and to see that the country people had all possible encouragement and freedom in their coming to the markets and going back again, and that no nuisances or frightful objects should be seen in the streets to terrify them or make them unwilling to come. Also the bakers were taken under particular order, and the Master of the Bakers' Company was, with his court of assistants, directed to see the order of my Lord Mayor for their regulation put in execution, and the due assize of bread (which was weekly appointed by my Lord Mayor) observed; and all the bakers were obliged to keep their oven going constantly, on pain of losing the privileges of a freeman of the city of London.