Полная версия:

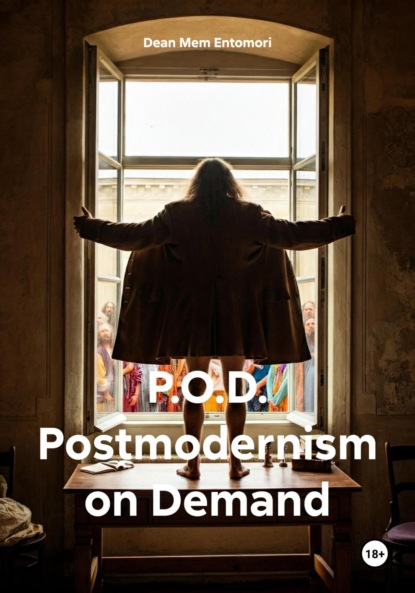

P.O.D. Postmodernism on Demand

Dean Mem Entomori

P.O.D. Postmodernism on Demand

Foreword

By Jonathan Quibble, Senior Editor at HagglerCollars Publishing

Dear Reader,

There are books that challenge you. There are books that confuse you. And then there are books like P.O.D. Postmodern on Demand—a book so bold, so utterly unhinged, it dares you to question whether it should exist at all.

When the manuscript first arrived at HagglerCollars, it came with no explanation. Just a file name (FINAL-FINAL-REALLY-FINAL.docx) and a cryptic email that read, “It’s done. Do what you will.” As I opened the file, I felt like an archaeologist dusting off an ancient artifact, unsure whether I was about to uncover a lost masterpiece or unleash a literary curse.

What I found defied all expectations. This is not just a book—it’s a labyrinth. A swirling, kaleidoscopic journey that teeters on the edge of brilliance and absurdity. It’s part satire, part philosophy, part… well, something else entirely.

Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr., the enigmatic mind behind this work, is no ordinary author. Known for his disdain for literary conventions and his unusual sources of inspiration, Tonny has a talent for turning the mundane into the extraordinary. His work is a mirror held up to our fractured world, reflecting its chaos, its humor, and its uncomfortable truths.

But let me be clear: this book is not for the faint of heart. It will challenge your assumptions. It will make you laugh, wince, and possibly rethink your relationship with modern technology and… other things. Yet, through it all, you’ll find yourself unable to look away.

What is P.O.D. truly about? I won’t spoil it for you. Some have called it a manifesto for our times. Others have called it a fever dream. All I’ll say is this: step into its pages, and prepare for a journey unlike any you’ve taken before.

Welcome to the world of Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr.

Sincerely,

Jonathan Quibble

Senior Editor, HagglerCollars Publishing

"In the end, life is just one big deadline. It starts with your birth certificate and ends with your obituary. In between, someone’s always asking: ‘Where’s the draft?’ And when the draft arrives, they’ll say: ‘This needs revisions.’ Because truth isn’t profitable. Stability is. And stability? It’s just crap dressed up as clarity.”

– Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr.

Chapter 1: Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr.

The email hit his inbox at 3:17 a.m. Like most emails from Human-Zone Kidney, it was a masterpiece of passive-aggressive brevity:

“Your Submission Requires Revisions.”

Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. sighed as he clicked the attachment. The manuscript looked like it had gone through a wood chipper of red comments. Every single one bore the same damning word: “Condemn.”

"They’re not condemning the text," he thought grimly, "they’re condemning me."

The phone buzzed. He let it ring once before reluctantly answering.

“Yeah?”

“Good morning, Mr. Pinchchitte,” a nasally voice said. “This is Alex, your moderator from Random Hassle. I’m calling from… uh… a mindfulness retreat in Colorado.”

“A retreat?” Tonny muttered, lighting a cigarette. “Fancy. What now?”

“Well,” Alex began hesitantly, “it’s about your manuscript. Our content guidelines flag several issues, especially around your, uh… characterization of majority figures.”

“Majority figures?” Tonny frowned.

“Yes, like… married, white, middle-class fathers,” Alex said, his voice dropping to a conspiratorial whisper. “Your protagonist is described as ‘tired,’ ‘overworked,’ and—how did you put it?—‘suffocating under the weight of societal expectations.’ That’s problematic.”

“Problematic for who?” Tonny asked, exhaling a stream of smoke.

“Well,” Alex continued, “we’re concerned it could be interpreted as sympathetic to, uh… traditional male archetypes. Readers might assume you’re… normalizing their struggle.”

Tonny barked out a laugh. “Normalizing their struggle? You mean, like waking up before everyone else, dying younger, and paying all the bills?”

“Exactly,” Alex said earnestly, as though Tonny had just solved a crossword puzzle. “That’s precisely the narrative we’re trying to avoid. Perhaps you could rewrite it to show how his behavior perpetuates systemic—”

“Let me stop you right there,” Tonny interrupted. “You want me to make the guy who pays for everything the villain?”

Alex sounded genuinely confused. “Well… yes. Isn’t he?”

Alex went on to explain that the Random Hassle editorial board, in collaboration with their AI, Big Condemn, had flagged over 73 “issues” in Tonny’s manuscript.

“For instance,” Alex said, “the phrase ‘exhausted father’ was replaced with ‘benevolent oppressor.’ And your scene where he helps his wife with the dishes? That needs to be reframed.”

“Reframed how?” Tonny asked, already regretting it.

“Maybe add an inner monologue where he’s angry about doing it,” Alex suggested. “That way it highlights his unconscious misogyny.”

“Misogyny?” Tonny nearly dropped his cigarette. “For doing the dishes?”

“Well,” Alex said cautiously, “it’s less about the act and more about what it symbolizes—an imbalance of power.”

Tonny muted the call and stared at the city below. Manhattan was waking up, the usual chaos unfolding in predictable patterns. A garbage truck rumbled past, and a jogger weaved between delivery bikes.

"So, now the guy who wakes up at 5 a.m., pays the mortgage, and dies before he can enjoy his retirement is the villain," he thought. "Sounds about right."

Unmuting the call, he said, “Alex, just to clarify, is there any character I can write about without getting flagged?”

“Well,” Alex hesitated, “we encourage characters that challenge societal norms.”

“So, no white, married fathers. What about a single dad who’s unemployed?”

“That could work,” Alex said cautiously, “as long as he’s an ally.”

“An ally to what?”

“Everything.”

After the call, Tonny sat at his laptop and tried to revise his manuscript. Every sentence felt like walking a tightrope over a pit of condemnation.

"When a man willingly consumes a wisdom shroom, spends years paying for everyone’s bills, and still gets blamed for the downfall of civilization, he eventually learns that the only way to survive is to become his own editor, moderator, and critic."

He paused, reread the line, and sighed:

"Condemn."

Outside, Manhattan roared with life, its chaos strangely comforting. Tonny stood, opened the window, and shouted into the void:

“Oh, Creator, and your legion of editorial angels! I condemn this! Myself, the moderators, the editors—even the algorithm running Big Condemn! Condemn it all!”

Below, a street vendor selling halal food glanced up and shrugged.

Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. was born into a family of self-proclaimed intellectuals in Greenwich Village. His father, a professor of “Post-Marxist Aesthetics” at NYU, spent most of his career deconstructing the semiotics of cereal box art. His mother, a librarian with a talent for euphemisms, could transform “bankruptcy” into “financial recalibration” with a straight face.

Tonny’s name was an act of rebellion. His father, enamored with commedia dell’arte, wanted to name him Pierrot but feared it was “too French.” Instead, he settled on Tonny—a name he believed combined theatrical flair with American pragmatism.

By ten, Tonny had already won his first writing competition. By sixteen, he’d alienated most of his classmates with his cutting intellect and refusal to “just go along.” He didn’t hate people; he simply couldn’t stand their predictability.

Even as a child, it was clear that Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. wasn’t like the others. Thoughtful, aloof, and dangerously observant, he had a way of commanding attention when it suited him—usually in the most inconvenient ways.

Teachers adored him for his sharp mind, but his classmates? Not so much. While the other boys chased soccer balls, Tonny preferred to engage his literature teacher in three-hour debates about why Bartleby the Scrivener wasn’t apathetic but rather a revolutionary figure rebelling against the tyranny of office work.

At the age of ten, Tonny won his first writing competition. Even then, he knew his true talent lay in crafting texts that gave readers the illusion they’d become smarter than they were a minute ago.

By sixteen, Tonny was painfully aware of one thing: he was brilliant. Too brilliant. And that brilliance was his curse.

Women often entered his orbit, but they never stayed long. From the very start, something about them repelled him—too predictable, too performative.

Tonny had an almost supernatural ability to detect manipulation. One glance, one subtle gesture, and he could tell exactly what he was dealing with: a romance novel addict trying to guilt him into devotion, or a drama queen pushing his patience to its limits.

“How primitive,” he once remarked to a friend over whiskey. “It’s as if they believe I can’t see the sheer boredom fueling their games.”

Tonny didn’t hate women. But he couldn’t accept them as they were in his life: mirrors, reflecting his significance back at him.

This detachment shaped his misanthropy, sharpening his already acidic wit and cementing his isolation. Every interaction felt like a transaction, every person another potential user.

By the time he turned twenty, Tonny had come to a grim conclusion: writing was his only escape.

He landed a modest gig at a niche publication, NeuroIndustries Monthly, where he penned a column titled The Mechanics of Consciousness. It was a bizarre blend of scientific jargon, armchair philosophy, and razor-sharp irony. And people loved it.

Letters poured in, praising his ability to make readers feel intellectually superior while also quietly questioning their own intelligence.

But there was one thing that always gnawed at him:

"People don’t read to understand. They read to feel better about themselves. It’s as if reading alone is enough to claim enlightenment."

This realization became the cornerstone of his early writing. Tonny didn’t want to write texts that merely impressed—he wanted to unsettle. He wanted his readers to squirm, to confront their own ignorance, and to grapple with the uncomfortable truth: that most of them were fools, and they didn’t even know it.

Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. was a man who rejected the world in order to understand it. His writing wasn’t a cry for connection; it was a scalpel, dissecting the absurdities of modern life with precision and ruthlessness.

He wasn’t interested in being liked. He wasn’t even interested in being read. He wrote for the sole purpose of watching the world squirm under the weight of its own contradictions.

And so, armed with his wit, his cynicism, and a perpetually smoldering cigarette, Tonny set out to do the one thing he knew he was born to do: write. Not for the masses. Not for the critics. But for himself—and perhaps for the slim chance that, somewhere out there, a reader might be smart enough to keep up.

Chapter 2: The Bahamian Lockdown Escape

Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. had been preparing for this moment his entire life.

The first whispers of a mysterious virus wafted in from China, accompanied by the usual barrage of American social media wisdom: “Is Corona just a fancy flu?” and “Did you hear? Bats are the new pigs!” While the rest of the country was busy panic-buying toilet paper and blaming everything on millennials, Tonny packed a single bag, booked a one-way ticket, and ghosted his entire existence.

His destination? Not the Bahamas you see in travel brochures, but a forgotten island that could generously be described as “the Florida of the Caribbean.” No five-star resorts. No tiki bars. Just a patch of sand, a smattering of shacks, and an economy that revolved around overpriced coconuts and mopeds that threatened to kill you every ten minutes.

Tonny’s bungalow, if you could call it that, stood isolated at the edge of the island, surrounded by mangroves and mosquitoes with lifespans longer than his patience. It had the kind of Wi-Fi that only worked when the wind blew west and a rusty old antenna that picked up TV signals from God-knows-where. That’s how Tonny first saw the news:

"BREAKING: America braces for COVID-19 lockdowns. Experts warn of widespread toilet paper shortages."

He switched off the TV, leaned back in his rickety wooden chair, and smirked. “Perfect. Global panic with no redeeming narrative. It’s like living in one of my books.”

His days passed in a haze of quiet monotony. He’d ride his sputtering moped into the village to buy groceries, spend hours staring at the horizon, and occasionally scribble half-thoughts into a battered notebook.

"Maybe I’m not condemning moderation itself," he mused one afternoon. "Maybe I’m just pissed off that I feel the need to condemn anything at all."

Chuckling at his own brilliance, he jotted it down.

Tonny had come to this forgotten island for one reason: anonymity. He wore a bandana, Ray-Bans, and a permanent scowl, confident that no one on an island where the only imported luxury was canned Spam would recognize him.

But Tonny had underestimated two things: the reach of American expats and his own cursed reputation.

It started with two women at the island’s only grocery store. One of them froze mid-reach for a can of beans, staring at him as if he were a rare bird.

“That’s him,” she whispered.

“No way,” the other replied, grabbing a box of cookies. “What would he be doing here?”

But Tonny heard them. He grabbed his bag of rice and left, heart sinking.

Over the next few days, the island’s tiny community began to buzz. Someone uploaded a blurry photo to Facebook:

"OMG, I swear Tonny Pinchshit is hiding out on [REDACTED] Island. Look at this! Total recluse vibes!"

From that moment, his peace was shattered.

The locals, bored to death by months of lockdowns, suddenly had a new pastime: Spot the Recluse Author.

They started following him, phones raised like paparazzi at a red carpet event.

“That’s him! Look at the hat! The walk! It’s totally Pinchshit!”

“He’s buying bananas. Should I post this?”

Before long, his bungalow turned into a full-blown tourist attraction. People knocked on the door at all hours, yelling:

“Tonny! We love you! Come out for a selfie!”

Others shone their phone flashlights through his windows, whispering, “It’s really him. I can see his notebook!”

And then came the emails and DMs:

"Why won’t you talk to us? Are you too good for your fans now? Disappointed, but not surprised."

One evening, as the mob outside chanted his name like he was the second coming of Hemingway, Tonny leaned against the wall of his bungalow and whispered:

“This is hell. Just pure hell.”

He realized he had no choice. He had to run.

Throwing on his Ray-Bans and stuffing a few essentials—his notebook, cash, and a suspiciously labeled jar of “herbal inspiration”—into a backpack, Tonny climbed out the window and bolted into the jungle.

The branches whipped his face, sand sucked at his feet, and the voices behind him grew louder:

“He’s running! Get your phones out!”

Finally, he reached the other side of the island, where he found a fisherman willing to take him to an even smaller, even less hospitable island—for a price that could have bought him a used car in Manhattan.

Weeks later, exhausted and still paranoid, Tonny found himself in the shadow of the Himalayas, hiding out in a forgotten mountain inn in northern India. The place was almost entirely abandoned, thanks to the pandemic.

“I want every room,” Tonny told the owner, an elderly man with the kind of wise gaze that could pierce through souls—or just appraise wallets.

The man nodded slowly. “No neighbors,” Tonny added firmly.

The old man raised an eyebrow, clearly wondering what kind of lunatic had wandered into his life, but eventually shrugged and handed over the keys.

For the first time in weeks, Tonny felt at peace. He brewed a cup of chai in the inn’s tiny kitchen, watching the mountains rise like silent sentinels beyond the horizon.

“This isn’t the Bahamas,” he muttered to himself. “But it’ll do. No one can find me here.”

He sipped his tea, savoring the silence, and thought, Maybe, just maybe, I’ve finally outrun the world.

Chapter 3: The Info-Baroness and Her “Flow”

It was the year of COVID, when half the world lived in pajamas, and the other half spent their days watching webinars in, well… pajamas. To his eternal shame, Tonny Rugless Pinchchitte Jr. belonged to the latter group.

One lazy afternoon, while scrolling through social media feeds crammed with sourdough bread and conspiracy theories, he froze. A bold, obnoxiously colorful ad demanded his attention:

"Neurographica for Creators: Draw Your Life. Find Your Flow!"

The ad featured a woman with unnaturally straight hair and a smile so dazzling it could double as a weapon. Her eyes gleamed with the unshakable confidence of someone who not only had all the answers but also knew the questions you hadn’t yet thought to ask.

“Draw my life…” Tonny muttered, squinting at her picture. “What if my life already looks like a vandalized alley wall?”

Still, something about the words “creator” and “flow” hooked him. Maybe it was boredom. Maybe it was the existential despair that came from realizing he’d already tried everything from digital life coaches to Tibetan “meditation elixirs” (which, in his case, were more like “disappointment tonics”).

With a resigned shrug, he clicked “Enroll.”

The course was led by an enigmatic info-preneur named Madura Shanti. In reality, her name was Marina Shapovalko, and her clipped vowels betrayed her origins somewhere near Cleveland—or maybe Kyiv. But her pseudonym had just enough exotic flair to spark hope in the desperate.

“Jest draw ze lines!” Madura chirped from the screen, her voice dripping with saccharine enthusiasm. “Feel ze flow! Smile—it is your weapon!”

“Weapon?” Tonny thought, raising an eyebrow. “Against what? Common sense?”

Nevertheless, he armed himself with a marker and a sheet of paper.

What followed could only be described as artistic chaos. His lines wobbled like a drunk snake, looping into shapes that resembled a toddler’s first attempt at finger painting. It was less “flow” and more “flat tire on a dirt road.”

“Why isn’t this working?” he muttered, staring at his mess of squiggles, which looked more like a racetrack for cockroaches than anything remotely spiritual.

But he persisted, reasoning that at least it kept him from drowning in cheap Bahamian rum during the lockdown.

One week into the course, Madura dropped a bombshell.

“Neurographica is… outdated,” she announced dramatically during a webinar. “The world is changing, and I am evolving with it. Now, I am a business coach! I awaken titans!”

“Titans?” Tonny choked on his coffee. “These titans probably build Babylonian towers out of credit card debt.”

Madura claimed her new method had helped people earn millions in just two months. Who these people were, she never clarified, but the confidence in her voice suggested the millions belonged to her.

The Neurographica course was abandoned, leaving Tonny with a stack of ruined paper and the sinking realization that, once again, he’d been swindled.

“Maybe this is her Neurographica,” he mused bitterly. “All the lines are crooked, but they somehow lead to one point—her bank account.”

As the pandemic spiraled out of control, Madura reinvented herself yet again. This time, she became a spiritual healer. Her new mantra?

“Breathe through your third chakra—it’s the cure for the virus!” she declared, her eyes gleaming with evangelical fervor during a livestream. “Vaccines? Why bother when you can align your energy centers?”

The “third chakra,” which she always mentioned with the same reverence one might reserve for a holy relic, was pitched as the ultimate trend. She insisted that proper breathing techniques could not only “open energy flows” but also “dismantle the molecular structure of the virus.”

“Viruses are just energetic noise!” she proclaimed. “Clear your chakras, and you’ll become invisible to disease!”

At the height of her fame, Madura launched an anti-vaccine campaign that drew thousands of followers. She recorded voice memos for her disciples:

“Don’t let fear control you! Your third chakra is your most powerful shield. Inhale, exhale, feel the flow!”

She filmed inspirational videos standing against sunsets, assuring viewers, “My chakra pulses so strongly, it protects my neighbors!”

But irony, as always, had the last laugh. When Madura inevitably caught COVID, no amount of breathing exercises could save her. Rumors about her condition spread quickly, but she maintained her serene facade:

“This is just a cleansing,” she insisted in a wheezy Instagram video. “My third chakra is expelling all negativity.”

Her final post became an unintentional masterpiece of absurdity. Gaunt, pale, and visibly struggling to breathe, she smiled at the camera and whispered:

“If I’m sick, it’s because the Universe is teaching me a greater lesson. Don’t worry—my chakra is winning.”

Weeks later, while scrolling through his inbox, Tonny stumbled upon an email with the subject line:

"Don’t Miss Out! 80% Off Madura Shanti’s Farewell Ceremony!”

The email featured a photo of Madura, her trademark smile beaming brighter than ever. Beneath it, a bold caption read:

"Exclusive opportunity to bid farewell to the guru and guide her to new heights of spiritual success!"

Tonny stared at the screen, then yawned. “Still hustling from beyond the grave,” he muttered.

The ceremony was set to take place at a rare cemetery in the Himalayan foothills, just a short hike from Tonny’s current hideout.

“Well,” he thought, “at least nobody there will recognize me. Everyone will be too busy talking about her chakras.”

The cemetery was tucked into the mountains, its entrance marked by a narrow trail that wound through charred black trees. The air smelled of incense—or maybe someone’s poorly concealed outdoor curry.

As Tonny climbed the mossy path, he couldn’t help but marvel at the absurdity of it all. “Who knew finding a graveyard in India was harder than finding a decent latte in Midtown?” he thought, slipping slightly on the damp ground.

Ahead, the Himalayan peaks rose like powdered sugar sculptures against a watercolor sky. It was beautiful, sure, but Tonny couldn’t shake the feeling that he’d just paid good money to attend a posthumous pyramid scheme.

“Even in death,” he muttered, “Madura still gets the last laugh.”

As Tonny Pinchchitte ascended the moss-covered trail, the view unfolded before him like an overpriced watercolor: jagged Himalayan peaks dusted with what looked like powdered sugar, the sky a cartoonish shade of blue so vibrant it seemed fake. The air carried a mix of woodsmoke and something oddly sweet—incense, perhaps, or maybe just someone burning last night’s failed curry.

In the distance, perched ominously near the cemetery, stood a sprawling colonial-style mansion. Its walls were blindingly white, the kind of white that makes your eyes ache just by looking at it. Ornate wooden balconies jutted out from the facade, and the faint scent of spices wafted through its open windows.

A massive billboard stood at the gates, garish and utterly out of place, its bold text screaming:

"Shambhala Is Closer Than You Think! Entry by Suggested Donation."

A group of men lounged on the front porch, dressed in flowing white robes that looked freshly laundered but deliberately wrinkled—enough to give them an air of authentic detachment. Their meticulously groomed beards practically radiated smugness, as if they weren’t just the keepers of Shambhala’s secrets, but also its majority shareholders.