Полная версия

Полная версияThe Posthumous Works of Thomas De Quincey, Vol. 1

XIX. INCREASED POSSIBILITIES OF SYMPATHY

IN THE PRESENT AGE

Some years ago I had occasion to remark that a new era was coming on by hasty strides for national politics, a new organ was maturing itself for public effects. Sympathy—how great a power is that! Conscious sympathy—how immeasurable! Now, for the total development of this power, time is the most critical of elements. Thirty years ago, when the Edinburgh mail took ninety-six hours in its transit from London, how slow was the reaction of the Scottish capital upon the English! Eight days for the diaulos27 of the journey, and two, suppose, for getting up a public meeting, composed a cycle of ten before an act received its commentary, before a speech received its refutation, or an appeal its damnatory answer. What was the consequence? The sound was disconnected from its echo, the kick was severed from the recalcitration, the 'Take you this!' was unlinked from the 'And take you that!' Vengeance was defeated, and sympathy dissolved into the air. But now mark the difference. A meeting on Monday in Liverpool is by possibility reported in the London Standard of Monday evening. On Tuesday, the splendid merchant, suppose his name were Thomas Sands, who had just sent a vibration through all the pulses of Liverpool, of Manchester, of Warrington, sees this great rolling fire (which hardly yet has reached his own outlying neighbourhoods) taken up afar off, redoubled, multiplied, peal after peal, through the vast artilleries of London. Back comes rolling upon him the smoke and the thunder—the defiance to the slanderer and the warning to the offender—groans that have been extorted from wounded honour, aspirations rising from the fervent heart—truth that had been hidden, wisdom that challenged co-operation.

And thus it is that all the nation, thus 'all that mighty heart,' through nine hundred miles of space, from Sutherlandshire by London to the myrtle climate of Cornwall, has become and is ever more becoming one infinite harp, swept by the same breeze of sentiment, reverberating the same sympathies

'Here, there, and in all places at one time.'28Time, therefore, that ancient enemy of man and his frail purposes, how potent an ally has it become in combination with great mechanic changes! Many an imperfect hemisphere of thought, action, desire, that could not heretofore unite with its corresponding hemisphere, because separated by ten or fourteen days of suspense, now moves electrically to its integration, hurries to its complement, realizes its orbicular perfection, spherical completion, through that simple series of improvements which to man have given the wings and talaria of Gods, for the heralds have dimly suggested a future rivalship with the velocities of light, and even now have inaugurated a race between the child of mortality and the North Wind.

FOOTNOTES:

XX. THE PRINCIPLE OF EVIL

We are not to suppose the rebel, or, more properly, corrupted angels—the rebellion being in the result, not in the intention (which is as little conceivable in an exalted spirit as that man should prepare to make war on gravitation)—were essentially evil. Whether a principle of evil—essential evil—anywhere exists can only be guessed. So gloomy an idea is shut up from man. Yet, if so, possibly the angels and man were nearing it continually.

Possibly after a certain approach to that Maelstrom recall might be hopeless. Possibly many anchors had been thrown out to pick up, had all dragged, and last of all came to the Jewish trial. (Of course, under the Pagan absence of sin, a fall was impossible. A return was impossible, in the sense that you cannot return to a place which you have never left. Have I ever noticed this?) We are not to suppose that the angels were really in a state of rebellion. So far from that, it was evidently amongst the purposes of God that what are called false Gods, and are so in the ultimate sense of resting on tainted principles and tending to ruin—perhaps irretrievable (though it would be the same thing practically if no restoration were possible but through vast æons of unhappy incarnations)—but otherwise were as real as anything can be into whose nature a germ of evil has entered, should effect a secondary ministration of the last importance to man's welfare. Doubt there can be little that without any religion, any sense of dependency, or gratitude, or reverence as to superior natures, man would rapidly have deteriorated; and that would have tended to such destruction of all nobler principles—patriotism (strong in the old world as with us), humanity, ties of parentage or neighbourhood—as would soon have thinned the world; so that the Jewish process thus going on must have failed for want of correspondencies to the scheme—possibly endless oscillations which, however coincident with plagues, would extirpate the human race. We may see in manufacturing neighbourhoods, so long as no dependency exists on masters, where wages show that not work, but workmen, are scarce, how unamiable, insolent, fierce, are the people; the poor cottagers on a great estate may sometimes offend you by too obsequious a spirit towards all gentry. That was a transition state in England during the first half of the eighteenth century, when few manufacturers and merchants had risen to such a generous model. But this leaves room for many domestic virtues that would suffer greatly in the other state. Yet this is but a faint image of the total independency. Oaths were sacred only through the temporal judgments supposed to overtake those who insulted the Gods by summoning them to witness a false contract. But this would have been only part of the evil. So long as men acknowledged higher natures, they were doubtful about futurity. This doubt had little strength on the side of hope, but much on the side of fear. The blessings of any future state were cheerless and insipid mockeries; so Achilles—how he bemoans his state! But the torments were real. By far more, however, they, through this coarse agency of syllogistic dread, would act to show man the degradation of his nature when all light of a higher existence had disappeared. That which did not exist for natures supposed capable originally of immortality, how should it exist for him? And that man must have observed with little attention what takes place in this world if he needs to be told that nothing tends to make his own species cheap and hateful in his eyes so certainly as moral degradation driven to a point of no hope. So in squalid dungeons, in captivities of slaves, nay, in absolute pauperism, all hate each other fiercely. Even with us, how sad is the thought—that, just as a man needs pity, as he is stript of all things, when most the sympathy of men should settle on him, then most is he contemplated with a hard-hearted contempt! The Jews when injured by our own oppressive princes were despised and hated. Had they raised an empire, licked their oppressors well, they would have been compassionately loved. So lunatics heretofore; so galley-slaves—Toulon, Marseilles, etc. This brutal principle of degradation soon developed in man. The Gods, therefore, performed a great agency for man. And it is clear that God did not discourage common rites or rights for His altar or theirs. Nay, he sent Israel to Egypt—as one reason—to learn ceremonies amongst a people who sequestered them. In evil the Jews always clove to their religion. Next the difficulty of people, miracles, though less for false Gods, and least of all for the meanest, was alike for both. Astarte does not kill Sayth on the spot, but by a judgment. Gods, no more their God, spake an instant law. Even the prophets are properly no prophets, but only the mode of speech by God,—as clear as He can speak. Men mistake God's hate by their own. So neither could He reveal Himself. A vast age would be required for seeing God.

But for the thought of man as evil (or of any other form of evil), as reconcilable with their idea of a perfect God, a happy idea may, like the categories, proceed upon a necessity for a perfect inversion of the methodus conspiciendi. Let us retrace, but in such a form as to be apprehensible by all readers. Analytic and synthetic propositions at once throw light upon the notion of a category. Once it had been a mere abstraction; of no possible use except as a convenient cell for referring (as in a nest of boxes), which may perhaps as much degrade the idea as a relative of my own degraded the image of the crescent moon by saying, in his abhorrence of sentimentality, that it reminded him of the segment from his own thumb-nail when clean cut by an instrument called a nail-cutter. This was the Aristotelian notion. But Kant could not content himself with this idea. His own theory (1) as to time and space, (2) the refutation of Hume's notion of cause, and (3) his own great discovery of synthetic and analytic propositions, all prepared the way for a totally new view. But, now, what is the origin of this necessity applied to the category as founded in the synthesis? How does a synthesis make itself or anything else necessary? Explain me that.

This was written perhaps a fortnight ago. Now, Monday, May 23 (day fixed for Dan Good's execution), I do explain it by what this moment I seem to have discovered—the necessity of cause, of substance, etc., lies in the intervening synthesis. This you must pass through in the course tending to and finally reaching the idea; for the analytical presupposes this synthesis.

Not only must the energies of destruction be equal to those of creation, but, in fact, perhaps by the trespassing a little of the first upon the last, is the true advance sustained; for it must be an advance as well as a balance. But you say this will but in other words mean that forces devoted (and properly so) to production or creation are absorbed by destruction. True; but the opposing phenomena will be going on in a large ratio, and each must react on the other. The productive must meet and correspond to the destructive. The destructive must revise and stimulate the continued production.

XXI. ON MIRACLES

What else is the laying of such a stress on miracles but the case of 'a wicked and adulterous generation asking a sign'?

But what are these miracles for? To prove a legislation from God. But, first, this could not be proved, even if miracle-working were the test of Divine mission, by doing miracles until we knew whether the power were genuine; i.e., not, like the magicians of Pharaoh or the witch of Endor, from below. Secondly, you are a poor, pitiful creature, that think the power to do miracles, or power of any kind that can exhibit itself in an act, the note of a god-like commission. Better is one ray of truth (not seen previously by man), of moral truth, e.g., forgiveness of enemies, than all the powers which could create the world.

'Oh yes!' says the objector; 'but Christ was holy as a man.' This we know first; then we judge by His power that He must have been from God. But if it were doubtful whether His power were from God, then, until this doubt is otherwise, is independently removed, you cannot decide if He was holy by a test of holiness absolutely irrelevant. With other holiness—apparent holiness—a simulation might be combined. You can never tell that a man is holy; and for the plain reason that God only can read the heart.

'Let Him come down from the cross, and we,' etc. Yes; they fancied so. But see what would really have followed. They would have been stunned and confounded for the moment, but not at all converted in heart. Their hatred to Christ was not built on their unbelief, but their unbelief in Christ was built on their hatred; and this hatred would not have been mitigated by another (however astounding) miracle. This I wrote (Monday morning, June 7, 1847) in reference to my saying on the general question of miracles: Why these dubious miracles?—such as curing blindness that may have been cured by a process?—since the unity given to the act of healing is probably (more probably than otherwise) but the figurative unity of the tendency to mythus; or else it is that unity misapprehended and mistranslated by the reporters. Such, again, as the miracles of the loaves—so liable to be utterly gossip, so incapable of being watched or examined amongst a crowd of 7,000 people. Besides, were these people mad? The very fact which is said to have drawn Christ's pity, viz., their situation in the desert, surely could not have escaped their own attention on going thither. Think of 7,000 people rushing to a sort of destruction; for if less than that the mere inconvenience was not worthy of Divine attention. Now, said I, why not give us (if miracles are required) one that nobody could doubt—removing a mountain, e.g.? Yes; but here the other party begin to see the evil of miracles. Oh, this would have coerced people into believing! Rest you safe as to that. It would have been no believing in any proper sense: it would, at the utmost—and supposing no vital demur to popular miracle—have led people into that belief which Christ Himself describes (and regrets) as calling Him Lord! Lord! The pretended belief would have left them just where they were as to any real belief in Christ. Previously, however, or over and above all this, there would be the demur (let the miracle have been what it might) of, By what power, by whose agency or help? For if Christ does a miracle, probably He may do it by alliance with some Z standing behind, out of sight. Or if by His own skill, how or whence derived, or of what nature? This obstinately recurrent question remains.

There is not the meanest court in Christendom or Islam that would not say, if called on to adjudicate the rights of an estate on such evidence as the mere facts of the Gospel: 'O good God, how can we do this? Which of us knows who this Matthew was—whether he ever lived, or, if so, whether he ever wrote a line of all this? or, if he did, how situated as to motives, as to means of information, as to judgment and discrimination? Who knows anything of the contrivances or the various personal interests in which the whole narrative originated, or when? All is dark and dusty.' Nothing in such a case can be proved but what shines by its own light. Nay, God Himself could not attest a miracle, but (listen to this!)—but by the internal revelation or visiting of the Spirit—to evade which, to dispense with which, a miracle is ever resorted to.

Besides the objection to miracles that they are not capable of attestation, Hume's objection is not that they are false, but that they are incommunicable. Two different duties arise for the man who witnesses a miracle and for him who receives traditionally. The duty of the first is to confide in his own experience, which may, besides, have been repeated; of the second, to confide in his understanding, which says: 'Less marvel that the reporter should have erred than that nature should have been violated.'

How dearly do these people betray their own hypocrisy about the divinity of Christianity, and at the same time the meanness of their own natures, who think the Messiah, or God's Messenger, must first prove His own commission by an act of power; whereas (1) a new revelation of moral forces could not be invented by all generations, and (2) an act of power much more probably argues an alliance with the devil. I should gloomily suspect a man who came forward as a magician.

Suppose the Gospels written thirty years after the events, and by ignorant, superstitious men who have adopted the fables that old women had surrounded Christ with—how does this supposition vitiate the report of Christ's parables? But, on the other hand, they could no more have invented the parables than a man alleging a diamond-mine could invent a diamond as attestation. The parables prove themselves.

XXII. 'LET HIM COME DOWN FROM THE CROSS.'

Now, this is exceedingly well worth consideration. I know not at all whether what I am going to say has been said already—life would not suffice in every field or section of a field to search every nook and section of a nook for the possibilities of chance utterance given to any stray opinion. But this I know without any doubt at all, that it cannot have been said effectually, cannot have been so said as to publish and disperse itself; else it is impossible that the crazy logic current upon these topics should have lived, or that many separate arguments should ever for very shame have been uttered. Said or not said, let us presume it unsaid, and let me state the true answer as if de novo, even if by accident somewhere the darkness shelters this same answer as uttered long ago.

Now, therefore, I will suppose that He had come down from the Cross. No case can so powerfully illustrate the filthy falsehood and pollution of that idea which men generally entertain, which the sole creditable books universally build upon. What would have followed? This would have followed: that, inverting the order of every true emanation from God, instead of growing and expanding for ever like a <, it would have attained its maximum at the first. The effect for the half-hour would have been prodigious, and from that moment when it began to flag it would degrade rapidly, until, in three days, a far fiercer hatred against Christ would have been moulded. For observe: into what state of mind would this marvel have been received? Into any good-will towards Christ, which previously had been defeated by the belief that He was an impostor in the sense that He pretended to a power of miracles which in fact He had not? By no means. The sense in which Christ had been an impostor for them was in assuming a commission, a spiritual embassy with appropriate functions, promises, prospects, to which He had no title. How had that notion—not, viz., of miraculous impostorship, but of spiritual impostorship—been able to maintain itself? Why, what should have reasonably destroyed the notion? This, viz., the sublimity of His moral system. But does the reader imagine that this sublimity is of a nature to be seen intellectually—that is, insulated and in vacuo for the intellect? No more than by geometry or by a sorites any man constitutionally imperfect could come to understand the nature of the sexual appetite; or a man born deaf could make representable to himself the living truth of music, a man born blind could make representable the living truth of colours. All men are not equally deaf in heart—far from it—the differences are infinite, and some men never could comprehend the beauty of spiritual truth. But no man could comprehend it without preparation. That preparation was found in his training of Judaism; which to those whose hearts were hearts of flesh, not stony and charmed against hearing, had already anticipated the first outlines of Christian ideas. Sin, purity, holiness unimaginable, these had already been inoculated into the Jewish mind. And amongst the race inoculated Christ found enough for a central nucleus to His future Church. But the natural tendency under the fever-mist of strife and passion, evoked by the present position in the world operating upon robust, full-blooded life, unshaken by grief or tenderness of nature, or constitutional sadness, is to fail altogether of seeing the features which so powerfully mark Christianity. Those features, instead of coming out into strong relief, resemble what we see in mountainous regions where the mist covers the loftiest peaks.

We have heard of a man saying: 'Give me such titles of honour, so many myriads of pounds, and then I will consider your proposal that I should turn Christian.' Now, survey—pause for one moment to survey—the immeasurable effrontery of this speech. First, it replies to a proposal having what object—our happiness or his? Why, of course, his: how are we interested, except on a sublime principle of benevolence, in his faith being right? Secondly, it is a reply presuming money, the most fleshly of objects, to modify or any way control religion, i.e., a spiritual concern. This in itself is already monstrous, and pretty much the same as it would be to order a charge of bayonets against gravitation, or against an avalanche, or against an earthquake, or against a deluge. But, suppose it were not so, what incomprehensible reasoning justifies the notion that not we are to be paid, but that he is to be paid for a change not concerning or affecting our happiness, but his?

XXIII. IS THE HUMAN RACE ON THE DOWN GRADE?

As to individual nations, it is matter of notoriety that they are often improgressive. As a whole, it may be true that the human race is under a necessity of slowly advancing; and it may be a necessity, also, that the current of the moving waters should finally absorb into its motion that part of the waters which, left to itself, would stagnate. All this may be true—and yet it will not follow that the human race must be moving constantly upon an ascending line, as thus:

nor even upon such a line, with continual pauses or rests interposed, as thus:

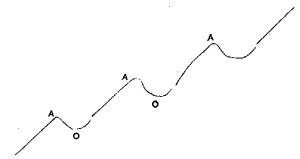

where there is no going back, though a constant interruption to the going forward; but a third hypothesis is possible: there may be continual loss of ground, yet so that continually the loss is more than compensated, and the total result, for any considerable period of observation, may be that progress is maintained:

At O, by comparison with the previous elevation at A, there is a repeated falling back; but still upon the whole, and pursuing the inquiry through a sufficiently large segment of time, the constant report is—ascent.

Upon this explanation it is perfectly consistent with a general belief in the going forward of man—that this particular age in which we live might be stationary, or might even have gone back. It cannot, therefore, be upon any à priori principle that I maintain the superiority of this age. It is, and must be upon special examination, applied to the phenomena of this special age. The last century, in its first thirty years, offered the spectacle of a death-like collapse in the national energies. All great interests suffered together. The intellectual power of the country, spite of the brilliant display in a lower element, made by one or two men of genius, languished as a whole. The religious feeling was torpid, and in a degree which insured the strong reaction of some irritating galvanism, or quickening impulse such as that which was in fact supplied by Methodism. It is not with that age that I wish to compare the present. I compare it with the age which terminated thirty years ago—roused, invigorated, searched as that age was through all its sensibilities by the electric shock of the French Revolution. It is by comparison with an age so keenly alive, penetrated by ideas stirring and uprooting, that I would compare it; and even then the balance of gain in well-calculated resource, fixed yet stimulating ideals, I hold to be in our favour—and this in opposition to much argument in an adverse spirit from many and influential quarters. Indeed, it is a remark which more than once I have been led to make in print: that if a foreigner were to inquire for the moral philosophy, the ethics, and even for the metaphysics, of our English literature, the answer would be, 'Look for them in the great body of our Divinity.' Not merely the more scholastic works on theology, but the occasional sermons of our English divines contain a body of richer philosophical speculation than is elsewhere to be found; and, to say the truth, far more instructive than anything in our Lockes, Berkeleys, or other express and professional philosophers. Having said this by way of showing that I do not overlook their just pretensions, let me have leave to notice a foible in these writers which is not merely somewhat ludicrous, but even seriously injurious to truth. One and all, through a long series of two hundred and fifty years, think themselves called upon to tax their countrymen—each severally in his own age—with a separate, peculiar, and unexampled guilt of infidelity and irreligion. Each worthy man, in his turn, sees in his own age overt signs of these offences not to be matched in any other. Five-and-twenty periods of ten years each may be taken, concerning each of which some excellent writer may be cited to prove that it had reached a maximum of atrocity, such as should not easily have been susceptible of aggravation, but which invariably the relays through all the subsequent periods affirm their own contemporaries to have attained. Every decennium is regularly worse than that which precedes it, until the mind is perfectly confounded by the Pelion upon Ossa which must overwhelm the last term of the twenty-five. It is the mere necessity of a logical sorites, that such a horrible race of villains as the men of the twenty-fifth decennium ought not to be suffered to breathe. Now, the whole error arises out of an imbecile self-surrender to the first impressions from the process of abstraction as applied to remote objects. Survey a town under the benefit of a ten miles' distance, combined with a dreamy sunshine, and it will appear a city of celestial palaces. Enter it, and you will find the same filth, the same ruins, the same disproportions as anywhere else. So of past ages, seen through the haze of an abstraction which removes all circumstantial features of deformity. Call up any one of those ages, if it were possible, into the realities of life, and these worthy praisers of the past would be surprised to find every feature repeated which they had fancied peculiar to their own times. Meanwhile this erroneous doctrine of sermons has a double ill consequence: first, the whole chain of twenty-five writers, when brought together, consecutively reflect a colouring of absurdity upon each other; separately they might be endurable, but all at once, predicating (each of his own period exclusively) what runs with a rolling fire through twenty-five such periods in succession, cannot but recall to the reader that senseless doctrine of a physical decay in man, as if man were once stronger, broader, taller, etc.—upon which hypothesis of a gradual descent why should it have stopped at any special point? How could the human race have failed long ago to reach the point of zero? But, secondly, such a doctrine is most injurious and insulting to Christianity. If, after eighteen hundred years of development, it could be seriously true of Christianity that it had left any age or generation of men worse in conduct, or in feeling, or in belief, than all their predecessors, what reasonable expectation could we have that in eighteen hundred years more the case would be better? Such thoughtless opinions make Christianity to be a failure.