Полная версия:

The Eddie Stobart Story

COPYRIGHT

HarperNonFiction

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2001

Copyright © Hunter Davies 2001

Hunter Davies asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007336616

Ebook Edition © OCTOBER 2016 ISBN: 9780008226503

Version: 2016-10-11

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Illustrations

Introduction

Where it all Began …

The Stobarts

Young Edward

Edward Goes to Work

Edward Goes to Town

Haulage – the Long Haul

Hello Carlisle

Pink Elephants

A Wedding and a Warehouse

Motorways Cometh

Edward Faces a Dilemma

The New Management Men

Branching Out

What Edward Did Upstairs

The Birth of the Fan Club

Bad-Mouthing

Money Matters

Daventry

The Fan Club Today

The Fans

Spin-Offs

Up the Management Men

Problems, Problems

Up the Workers

The Firm Today – and its Future

Expert Witnesses

The Stobarts Today

Edward Today

Appendices

A Haulage Glossary

B The Stobarts: a Who’s Who

C Eddie Stobart Limited: Chronology

D Lorry Names

E Eddie Stobart Fan Club

F Eddie Stobart Depots

G Top Haulage Firms: 2000

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

ILLUSTRATIONS

Section One

1 John Stobart’s wedding

2 Young Eddie Stobart with his family

3 Caldbeck, Cumberland

4 Eddie and Nora’s wedding

5 Edward, Anne and John

6 Edward at primary school

7 Edward, Anne, William and John

8 The family: (sitting, left to right) William, Nora, Eddie, Anne (standing) Edward and John

9 The farm shop at Wigton

10 Eddie Stobart Ltd at the Cumberland show in the early Seventies

11 An early Scania lorry, drives through Hesket

12 Freshly washed lorries at Greystone Road

13 Edward with drivers Bob McKinnel and Neville Jackson

14 Edward at Greystone Road

15 The new Kingstown site, bought in 1980

16 William and Edward in the early Kingstown days

17 Edward’s wedding to Sylvia, in 1980

18 William with his truck

19 The first Stobart vehicle in Metal Box livery – 1987 (left to right) Colin Rutherford, Stuart Allan, Edward

Section Two

1 The Wurzels performing ‘I Want to be an Eddie Stobart Driver’

2 The Blackpool illuminations, featuring Eddie Stobart Ltd – 1995

3 Charity panto event

4 Eddie Stobart trucks setting off for Romania

5 The Kingstown depot

6 Princess Anne and Edward, at the opening of the Daventry site

7 The huge Daventry depot today

8 The beginning of 25-anniversary celebrations at the Dorchester

9 Edward celebrating with Jools Holland

10 Celebrating with the truck Twiggy

11 Barrie Thomas

12 David Jackson

13 Colin Rutherford

14 Norman Bell’s retirement in 1990

15 Linda Shore in the fan club shop

16 Truck driver Billy Dowell

17 Carlisle United Football Club – 1997

18 William today

19 Edward and Nora today

20 Edward with William Hague

21 Edward receiving the ‘Haulier of the Year’ award

22 Edward with Deborah Rodgers

INTRODUCTION

Edward Stobart is Cumbria’s greatest living Cumbrian. Not a great deal of competition, you might think, as Cumbria is a rural county, with only twenty settlements with a population greater than 2500. But our native sons do include Lord Bragg.

I used to say the greatest living Cumbrian was Alfred Wainwright, though he was a newcomer, who assumed Cumbrian nationality when he fell in love with Lakeland and then moved to Kendal. Wainwright, like Eddie Stobart, became a cult, acquiring an enormous following without ever really trying. In fact Wainwright discouraged fans, refusing to speak to other walkers when he met them, not allowing his photograph to appear on his guide books, never doing signing sessions. Yet he went on to sell millions of copies of his books.

Edward Stobart, the hero of this book, not to be confused with his father, Eddie Stobart, still lives in Cumbria and the world HQ of Eddie Stobart Limited is still in Carlisle. In the last ten years, it has become a household name all over the country, at least in households who have chanced to drive along one of our motorways, which means most of us. Today, the largest part of his business is now situated elsewhere in England, yet Edward remains close to his roots.

I am a fellow Cumbrian, so I boast, if not quite a genuine one as I was born in Scotland, only moving to Carlisle when I was aged four. But I know whence the Stobarts have come, know well their little Cumbrian home village, know many of their friends – and that to me is one of the many intriguing aspects of their rise. How did they get here, from there of all places?

I had met Edward, before beginning this book, at the House of Lords, guests of the late Lord Whitelaw. It was a reception for Ambassadors for Cumbria, a purely honorary title, dreamed up by some marketing whiz. I talked to Edward for a while, but didn’t get very far. He doesn’t go in for idle chat, doesn’t care for social occasions, doesn’t really like talking much, being hesitant with strangers, very reserved and private. Despite the firm’s present-day fame, I can’t remember seeing him interviewed on television, hearing him on the radio and I seldom see his face in the newspapers.

So this was another thought that struck me. Having got from there, that little village I used to know so well, how did Edward Stobart then become a national force, when he himself appears so unpushy, unfluent, undynamic?

The fact that he has risen to fame and fortune through lorries, creating the biggest private firm in Britain, is also interesting. It’s so unmodern, unglamorous. He’s now regularly on The Sunday Times list of the wealthiest people in Britain but, unlike so many of the other entries, he actually owns things. There is a concrete, physical presence to his fortune. The wealth of many of our present-day self-made millionaires is very often abstract, either on paper or out there on the ether; liable to fall and disappear in a puff of smoke or a blank screen.

Haulage is old technology; so old it’s practically prehistoric. Hauling stuff from A to B, real stuff as opposed to messages and information, has always been with us. And over the centuries it has sent out its own messages, giving us clues to the state of the economy, the state of the nation. By following the rise of our leading haulage firm over the last thirty years, since Eddie Stobart Limited was created in 1970, we should also be able to observe glimpses of the history of our times.

The cult of Eddie Stobart: that’s perhaps the most surprising aspect of all. How on earth has a lorry firm acquired a fan club of over 25,000 paid-up members? You expect it in films or football, in TV or the theatre, with people in the public eye, who have staff to push or polish their name and image. But lorries are just objects. They don’t sign autographs. Hard to get them to smile to the camera. Not many have been seen drunk or stoned in the Groucho Club. Some would say they are nasty, noisy, environmentally-unfriendly, inanimate objects – not the sort of thing you’d expect right-thinking persons to fall in love with.

I wanted to find out some of the answers to these questions, some sort of explanation or insight. I also wanted to celebrate my fellow Cumbrian. Hold tight then, here we go, full speed ahead, with possibly a few diversions along the way, for a ride on the inside with Eddie Stobart.

Hunter Davies

Loweswater, August 2001.

WHERE IT ALL BEGAN …

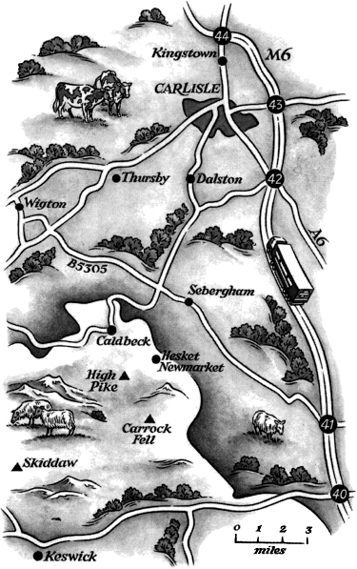

Caldbeck and Hesket Newmarket are two small neighbouring villages on the northern fringes of the Lake District in Cumbria, England. They are known as fell villages, being on the edges of the fells, or hills, where the laid out, captured fields and civilized hedges and obedient tarmac roads give way to unreconstructed, open countryside. A place where neatness and tidiness meet the rough and the unregimented. A bit like some of the people.

The first of the two most prominent local fells is High Pike, 2159 feet high, which looms over Caldbeck and Hesket, with Carrock Fell hovering round the side. Behind them, in the interior, there are further fells, unfolding in the distance, till you reach Skiddaw, 3053 feet high, Big Brother of the Northern Fells. A mere pimple compared with mountains in the Himalayas, but Skiddaw dominates the landscape and the minds of the natives who have always referred to themselves as living ‘Back O’ Skiddaw’.

Once you leave the fields, the little empty roads, and get on to the fell side, in half an hour you can be on your own, communing with nature. People think it can’t be done, that the whole of Lakeland is full, the kagouls rule, but this corner is always empty. My wife and I had a cottage at Caldbeck for ten years and we used to do fifteen-mile walks, up and across the Caldbeck Fells, round Skiddaw, down to Keswick and, in eight hours, meet only two or three other walkers. Then we got a taxi back, being cheats.

You see few people because this is not the glamorous, touristy Lake District. There are no local lakes. It’s hard to get to, especially if you are coming up from the South, as most of the hordes do. There used to be a lot of mining, so you still come across scarred valleys, jagged holes, dumps of debris. It’s an acquired taste, being rather barren and treeless, often windy and misty, colourless for much of the year, though, in the autumn, the fell slopes turn a paler shade of yellow.

At first sight, first impression, it’s not exactly a welcoming place. The people and the landscape tend to hide their delights away. Like the fells, friendships unfold. ‘They’ll winter you, summer you, winter you again,’ so we were told when we first moved to Caldbeck. ‘Then they might say hello.’

The nearest big town is Carlisle, some fifteen miles away, a historic city with a castle and cathedral, small as cities go, with only 70,000 citizens. It is, however, important as the capital of Cumbria, the second largest county in England – only in area, though; in population, Cumbria is one of the smallest, with only 400,000 people. Carlisle is in the far north-western corner of England, hidden away on the map and in the minds of many English people, who usually know the name but aren’t quite sure if it might be in Scotland or even Wales.

The region, it would seem at first glance, is an unlikely, unpromising setting to produce such a family as the Stobarts. At a second glance, when you look further into their two home villages, you find more colour, more depth, more riches hidden away.

Caldbeck is the bigger village of the two, population six hundred, and has a busy, semi-industrial past. The old mill buildings have now been nicely refurbished to provide smart homes or workshops. It still is a thriving village, a genuine, working village, as all the locals will tell you. It does not depend on tourists, trippers or second-homers. It’s got a very active Young Farmers Club, a tennis club, amateur dramatics. There are agricultural families who have been there for centuries, mixing well with a good sprinkling of newer, middle-class professionals who work in Carlisle.

Caldbeck’s claims to national fame lie in its graveyard. At the parish church is buried the body of John Peel, a local huntsman, commemorated in a song which is Cumbria’s national anthem and gets sung all round the English-speaking world. (Peel never heard it himself – the words were put to the present tune after his death.) Near him lies Mary Robinson, the Maid of Buttermere, a Lakeland beauty who was wronged by a rotter in 1802. He bigamously married her and was later hanged, a drama which thrilled the nation and became a London musical. More recently, it was turned into a successful novel by Melvyn Bragg. Lord Bragg, as he now is called, was brought up and educated at Wigton, a small town, about ten miles from Caldbeck. He is a great lover of the Caldbeck Fells and still has a country home locally at Ireby.

Caldbeck’s church is named after St Kentigern, known as St Mungo in Scotland, who was a bishop of Glasgow. He visited the Caldbeck area in 553 and did a spot of converting after he heard that, ‘many amongst the mountains were given to idolatory’. Much later, the early Quakers were very active in this corner of Cumbria, as were Methodist missionaries.

Hesket Newmarket, just over a mile away from Caldbeck, is very small, with only a few dozen houses. It is quieter, quainter than Caldbeck, a leftover hamlet from another age, one of the most attractive villages in all Cumbria and very popular with second-homers, many of whom live and work in the north-east. It’s basically one street which has some pretty eighteenth-century cottages lining a long, rolling village green. In the middle is the old Market Cross, admired by Pevsner for its ‘four round pillars carrying a pyramid roof with a ball finial.’ Until recently, it was used as the village’s garage.

There were five pubs here at one time. Now there’s only one, the Old Crown, well known in real beer circles as it brews its own beer. There used to be a local school, known as Howbeck, just outside the village, which all the Stobarts attended but it is now a private home. It was opened, along with Caldbeck’s village school (still going strong) in 1875 to ensure rural children received the same education as urban children. A School Inspector’s report for 14 May 1890, observed that: ‘a remarkable occurrence took place on Monday afternoon – viz, every child was present.’

Hesket Newmarket did have a market, established in 1751 for sheep and cattle, but it was discontinued by the middle of the nineteenth century. Hesket’s annual agricultural show, held since 1877, is still a big event, featuring Cumberland and Westmorland wrestling, hound trails as well as agricultural exhibits. It draws crowds and entrants from all over the county.

William Wordsworth, plus sister Dorothy and Coleridge, stayed at Hesket on 14 August 1803. Dorothy recorded their visit in her journal: ‘Slept at Mr Young-husband’s publick house, Hesket Newmarket. In the evening walked to Caldbeck Fells.’

Coleridge described the inn’s little parlour. ‘The sanded stone floor with the spitting pot full of sand dust, two pictures of young Master and Miss, she with a rose in her hand … the whole room struck me as cleanliness quarrelling with tobacco ghosts.’

In September 1857, Charles Dickens and fellow novelist Wilkie Collins visited the village in order to climb Carrock Fell. They later wrote up their trip in The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices. They managed to get to the top of Carrock Fell in the rain, moaning all the way, but coming down, Wilkie Collins sprained an ankle.

They, too, described the parlour in which they stayed, amazed by all the ‘little ornaments and nick-nacks … it was so very pleasant to see these things in such a lonesome by-place … what a wonder this room must be to the little children born in the gloomy village, what grand impressions of those who became wanderers over the earth, how at distant ends of the world some old voyagers would die, cherishing the belief that the finest apartment known to men was once in the Hesket Newmarket Inn, in rare old Cumberland …’

I’m sure the locals didn’t like the reference to their ‘gloomy’ village but it shows that Hesket, however hidden away, has attracted some eminent people over the centuries.

The present-day best-known resident of Hesket is Sir Chris Bonington, the mountaineer and writer: a Londoner by birth, but a Cumbrian by adoption. He bought a cottage at Nether Row, just outside Hesket, on the slopes of High Pike, in 1971 and has lived there full time since 1974. He is a co-owner of the Old Crown pub. It doesn’t quite put him on the level of a Scottish and Newcastle or Guinness director: the Old Crown is now a co-operative, with sixty local co-owners.

Chris has no intention of ever leaving the area. He likes the local climbing, either doing hair-raising rock stuff over in Borrowdale or brisk fell walks straight up High Pike from his own back garden. In summer, he can manage two days in one: a working day, writing inside, then an evening day, outside at play till at least ten o’clock, as the nights are so light. ‘I love the quietness up here,’ he says, ‘well away from the Lake District rush. I also think it’s beautiful. I like the rolling quality, the open fells merging with the countryside. In fact, my favourite view in all Lakeland is a local one: from the road up above Uldale, looking back towards Skiddaw.’

As a neighbour of the Stobart clan, Chris has watched their rise and rise, but doesn’t think you can make generalizations about them or their background: ‘What I will say, from my observations, is that the Cumbrian is shrewd.’

Chris is currently watching the rise of another local family business from a similar background: known, so far, only in the immediate area. The founder, George Steadman, was the village blacksmith in Caldbeck in the 1900s. His son built barns. In turn, his son, Brian the present Managing Director, moved on to roofing and cladding for industrial buildings. Over the last twenty years, Brian Steadman and his wife, Doreen, have been doubling their business every year. They now employ sixty people and last year turned over nine million pounds.

Visitors to the Caldbeck area driving back into Carlisle, down Warnell Fell, will notice the Steadmans’ new factory on the left-hand side. When I drive past, I always turn my head in admiration, taking care not to crash as it is a very steep hill. Their front lawns are so immaculate, their buildings all gleaming, yet it’s only a boring old factory, producing boring old roofing material.

‘We didn’t used to be so tidy when we were based in Caldbeck,’ says Brian. ‘It was partly the influence of Eddie Stobart Ltd. We did a big roofing job for them in Carlisle, big for us: £400,000 it was and they paid us on the dot, which very few firms do these days.

‘Anyway, while we were doing that job, I noticed how neat and tidy all his lorries were, and his premises, and how smart his staff were. We all know how successful Eddie Stobart Ltd has been. I thought we’d try to follow his lead.’

The Steadmans are following Eddie Stobart from the same local environment. Is this just by chance, perhaps, or do they think there are any connections, any generalizations to be made? ‘I think what it shows,’ says Doreen, ‘is that people who leave school early, such as Brian and the Stobarts, who are no good academically but are good with their hands, can still create good businesses.’

‘I think with us and the Stobarts,’ says Brian, ‘it’s been an advantage being country people. Country staff are loyal, reliable people. They stick with you, through thick and thin. You need that in the difficult times, which all firms go through.’

Perhaps, then, it’s not at all surprising for successful businesses to come out of a remote, rural area. Country folk are shrewd, says Bonington. Country folk are loyal, says Steadman.

Country folk can do it, as has been shown in the past. One of Cumbria’s all-time successful business families came from Sebergham, the very next village after Hesket. In 1874, the village stonemason, John Laing, moved into Carlisle and set himself up as a builder. Today, Laing’s are still building all over the civilized world. So much for nothing happening, nothing ever coming out of such a remote rural region.

THE STOBARTS

The Cumbrian branch of the Stobarts can trace their family back pretty clearly for around one hundred years, all of them humble farming folk in the Caldbeck Fells area. Before that, it gets a bit cloudy. Sometime early in the nineteenth century, so they think, the original Stobart is supposed to have come over to Cumberland from Northumberland, but that is just a family rumour. Originally, they could have been Scottish, or at least Border folk, as their surname is thought to have derived from ‘Stob’, an old Scottish word for a small wooden post or stump of a tree.

The founder of the present family was John Stobart, father of Eddie and grandfather of Edward. He was born at Howgill, Sebergham, in 1903 and worked at his father’s farm on leaving school. In 1930, he secured his own smallholding of some thirty-two acres at Bankdale Head, Hesket Newmarket. By this time he had got married to Adelaide, known as Addie, and they had a baby son, Edward Pears Stobart – always known as Eddie – who was born in 1929. Eddie was followed by a second son, Ronnie, in 1936.

On John’s smallholding, he kept eight cows, a bull, some horses and three hundred hens. Farming, and life in general, was hard at the end of the 1930s so, to bring in a bit more money and feed his young family, John managed to secure some work with the Cumberland County Council, hiring out himself plus his horse and cart, on occasional contract jobs.

John’s wife, Addie, died in 1942. John then married again, to Ruth Crame, whose family had come up from Hastings to Hesket Newmarket during the War to escape the bombing. He went on to have six other children by Ruth: Jim, Alan, Mary, Ruth, Dorothy and Isobel. Hence the reason why there are so many Stobarts in and around the Hesket area today.