Полная версия:

Leviathan: The Rise of Britain as a World Power

LEVIATHAN

The Rise of Britain as a World Power

DAVID SCOTT

For Sarah

CONTENTS

Title Page

Dedication

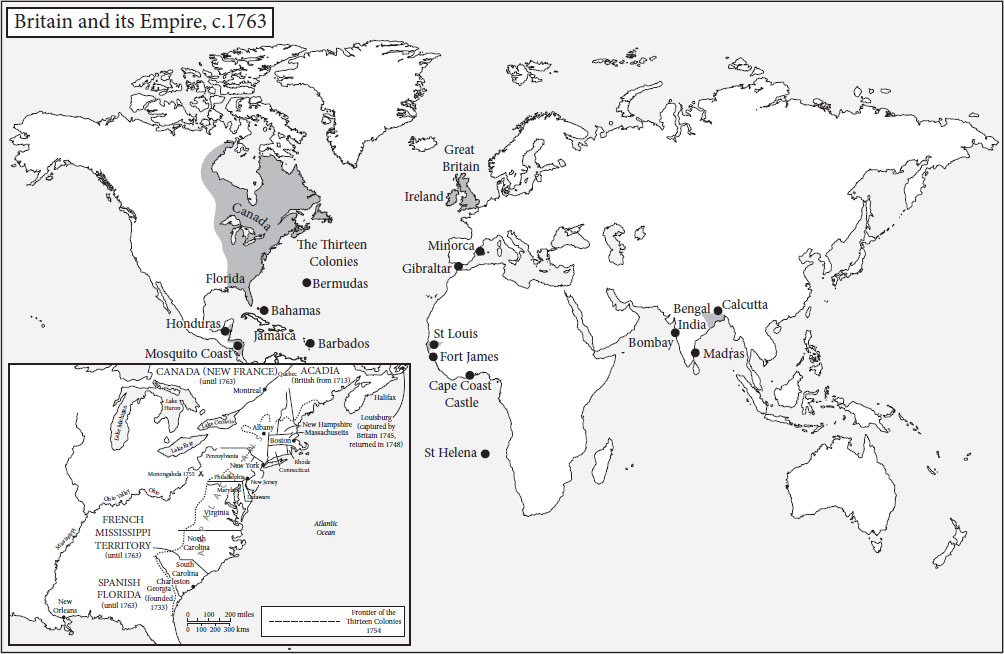

Maps

List of Illustrations

Preface

Lost Kingdoms, 1485–1526

The Protestant Cause, 1527–1603

Free Monarchy, 1603–37

Behemoth and Leviathan, 1637–60

The French Connection, 1660–1714

The Balance of Europe, 1714–54

Greatness of Empire

New World Order, 1754–83

Epilogue

Bibliography

Notes

Picture Section

Acknowledgements

Also by David Scott

Copyright

About the Publisher

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. King Henry VII by unknown Flemish artist, 1505 (© National Portrait Gallery, London. NPG 416)

2. From The Image of Irelande by John Derrick, 1581 (Courtesy Edinburgh University Library)

3. Armada playing cards, 1588 (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PU0214; PU0183; PU0181; PU0179)

4. From Narratio regionum indicarum per Hispanos quosdam devastatarum verissima, 1598 (Courtesy Bibliothèque Nationale de France. BNF C43328)

5. Equestrian portrait of Charles I by Anthony Van Dyck, 1633 (Supplied by Royal Collection Trust / © HM Queen Elizabeth II 2013. RCIN 405322)

6. The Tiger by William Van de Velde the elder, c.1681 (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PZ7304)

7. View of the beheading of Charles I by unknown artist (Private Collection / © Look and Learn / Peter Jackson Collection / The Bridgeman Art Library)

8. East India Company Ships at Deptford by unknown artist, c.1660 (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. BHC1873)

9. Duke’s plan of New York, 1664 (© The British Library Board. Maps K.Top.CXXI.35. 008318)

10. Engraving of London before the Great Fire by Pieter Hendricksz Schut, mid-17th century (Courtesy Guildhall Library, City of London)

11. A Representation of the Popish Plot in 29 figures, c.1678 (© The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 1871,1209.6512)

12. The Common wealth ruleing with a standing Army, 1683 (© The Trustees of the British Museum. All rights reserved. 1868,0808.3297)

13. Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme by William Hogarth, 1721

14. Excise in Triumph, c.1733 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

15. Idol-Worship or The Way to Preferment, 1740 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

16. The Lyon in Love, 1738 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

17. O the Roast Beef of Old England (The Gate of Calais) by William Hogarth, 1748, engraved by C. Mosley (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

18. Beer Street by William Hogarth, 1751

19. Gin Lane by William Hogarth, 1751

20. The Abolition of the Slave Trade by Isaac Cruikshank, 1792 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

21. Slaves processing sugar cane, c.1667–71 (© The British Library Board. C13236-18)

22. Fort St George on the Coromandel Coast by Jan van Ryne, 1754 (© National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. PU1845)

23. The Ballance, or The American’s Triumphant, 1766 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

24. The Mob destroying & Setting Fire to the Kings Bench Prison & House of Correction in St Georges Fields, 1780 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

25. The Free-born Briton or A Perspective of Taxation, 1786 (Courtesy of The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University)

While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material reproduced herein, the publishers would like to apologise for any omissions and would be pleased to incorporate missing acknowledgements in future editions.

PREFACE

As Britain entered upon another global war with her old enemy France in the mid-1750s, the Royal Navy took timely delivery of the largest warship in the world. Built at Woolwich Dockyard and launched in 1756, the three-decker Royal George was a vast and intricately designed killing machine. Her construction had taken almost ten years and had consumed the wood of more than 5,000 oak and elm trees. She carried the tallest masts and the greatest spread of canvas of any ship in the navy. A crew of 867 men and boys was needed not only to sail her but also to work the hundred guns she mounted, which included twenty-eight massive ‘full cannon’ – the heaviest pieces of ordnance afloat – each firing a hull-smashing 42-pound ball. One broadside alone would throw over 1,000 lb weight of metal. Two broadsides were enough to sink the French 74-gun Superbe at the battle of Quiberon Bay in 1759 – the decisive naval engagement of the Seven Years War. Nelson’s flagship at Trafalgar in 1805, named Victory to commemorate Britain’s ‘year of victories’ in 1759, would be modelled on the Royal George. Ships of the line such as these were the ultimate expression of Britain’s determination to stamp her naval superiority on every European rival, or indeed combination of rivals. The British would tolerate no balance of power at sea as they would on the Continent. But the Georgian navy served a larger purpose than engaging enemy fleets, for it kept the sea lanes open to the stream of goods to and from Britain that invigorated its industries, powered its economy towards the industrial revolution, and sustained the military expenditure of an altogether deadlier war machine: the British imperial state.

This book is partly about how and why the British and Irish peoples acquired the kind of state that could outdo the French and every other European power; that could build the Royal George and keep her, and hundreds more warships, at sea around the globe for months on end. It is a story that grew to encompass all of Britain and Ireland, and many other lands besides. But it began life in England. And here I must pause to make the familiar confession of English historians writing supposedly ‘British’ history. It was said of Georgian Britain’s longest-serving prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, that his political genius consisted in ‘understanding his own country, and his foible, inattention to every other country, by which it was impossible he could thoroughly understand his own’.1 Though I do not lay claim to Walpole’s superlative mastery of his art, there is no doubt that I share his foible. In my own defence I would argue that in writing a narrative history that covers (if only loosely) Britain and Ireland, it is almost impossible to avoid focusing on England. There is no ignoring the fact that England was the largest, the most populous and the most aggressive of the states that occupied the British Isles during the period covered by this book. Events in London and lowland England were bound to exert a greater influence over Scotland and Ireland than the other way round.

This unavoidable Anglocentrism is also apparent in the period I have chosen to cover – that is, from 1485 to 1783. Henry Tudor’s victory at Bosworth in 1485 was, or would become, an event of immense significance in English history, but it looks rather less of a turning-point when viewed from a Scottish or Irish perspective. The capacity of the English to throw their weight around in the British Isles was unusually weak at the end of the fifteenth century – a legacy of the Wars of the Roses. Henry’s seizure of the crown took some time to disturb the pattern of English rule in Ireland, and longer still to make any great impact on the Stuart kingdom of Scotland. By contrast, the cataclysm of the American War of Independence, with which this book ends, reverberated immediately and powerfully across the British Isles. Yet although Bosworth itself was more of an Anglo-French event than a British or Irish one, the year 1485 is of larger significance than simply as a boundary marker between the Plantagenets and the Tudors. Henry VII’s reign (1485–1509), it is now recognised, did much to reshape and reinvigorate the English monarchy – which was, after all, the most powerful political institution in the British Isles. Moreover, the decades around 1500 have often been taken to mark the end of the Middle Ages in Britain and the beginning of a new era, the ‘early modern period’. Although historians (myself included) are vague about the timing and nature of this transition, the early modern period is generally assumed to have included the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and some, or most, of the eighteenth century – in other words, roughly the period covered by this book.

Writing history entails the risk of imposing order and meaning where none existed. Whether the early modern period has themes and trends that are peculiarly its own, or is merely a convenient label for the centuries between the end of the Middle Ages and the first stirrings of the industrial revolution, is too large a question for a preface, and too abstract for a narrative history. What is certainly true is that this period covers some very important historical territory for a proper understanding of modern Britain. The Reformation in England and Scotland in the sixteenth century wrought perhaps the most profound and enduring transformation in British and Irish society – for Catholics as well as Protestants – of anything that has happened in these islands since the Norman Conquest. The consequences of Britain’s traumatic break with medieval Christendom are still with us today, as are those of another innovation closely associated with the Reformation, and the early modern period more generally: printing. Britain’s first printing press was set up by William Caxton in 1476. The print revolution changed the way people read and wrote, thought and communicated, and how they perceived their nation and their relationship to the crown. Print was a vital medium by which London in particular, but also Edinburgh and Dublin, extended their authority and influence across the British Isles to create at least some of the attributes of a single political and cultural system. The partial incorporation of Ireland and Scotland by a London-dominated British state took place largely during the early modern period. And running through this story of the forging of modern Britain are the plot-lines, the dramatic twists and the heroes and villains of a true epic: the rise and fall of the ‘first’ British empire across the Atlantic.

These themes will carry the burden of my story, but there are also significant subplots that I thought worth unravelling. The development of representative institutions in the British Atlantic; the deepening and widening commitment to ideas of freedom and the rule of law (which ultimately enabled the colonial American cubs to defy the parental British lion); the consolidation of a political culture built around ideas of rights and the answerability of monarchs to their subjects – a process that was fitful, occasionally bloody, and at various times highly uncertain of outcome – and the emergence, by the late seventeenth century, of a degree of religious tolerance that had no parallel in any major European state.

Yet if the history of early modern Britain is not devoid of overarching themes, nor is it without deep fissures. Two are central to my narrative. The first and most obvious is the Reformation of the sixteenth century and, in particular, the way Protestantism altered how people in Britain related to the rest of Europe. From the 1550s there was a growing number of British Protestants who recognised no greater cause than fighting alongside their co-religionists in Europe in the great cosmic struggle against ‘popery’ – Catholicism understood as political and spiritual tyranny. Mere national security by means of a strong navy was the very least of their demands. They continually urged their monarchs to send armies to the Continent, and fleets to the New World, to uphold the Protestant cause. A few would be bolder still, and embrace the idea of the new and massively enlarged state that the British would have to build if they were properly to challenge the might of Catholic Europe.

The second great fissure in the history of early modern Britain occurred in the 1640s, and would see precisely that: the construction of a monstrous, militaristic state. And yet the circumstances surrounding the birth of this Leviathan would frustrate the dreams of a Protestant crusade abroad for half a century. In the end it would require a Dutch invasion to put Britain firmly and unstoppably on the path to global ascendancy. That ascendancy, both real and imagined, would frequently be challenged by the Dutch themselves, the French, the Spanish, and by Britain’s own colonial subjects. What was special about the state that emerged in Britain in the mid-seventeenth century was not so much its power as its resilience. One of my aims has been to explain how the growth of such a state enabled the British not simply to win an empire, but to survive and indeed flourish after losing more than half of it – a setback that would have overwhelmed a lesser imperial power.

There are many ways of telling this story of wars and empire, and of the fears and dreams that made them. I have chosen to look more closely at those pursuing and exercising power than at the instruments and victims of their ambition. If this too is a foible on my part, it also has some grounding in historical fact. In our democratic society, the wishes and opinions of the majority are constitutive of the political order. Until the 1800s, however, democracy was merely a polite word for mob rule, and barely a thought was given to empowering women. The social, economic and intellectual structures that prevailed in early modern Britain allowed small groups of men to exercise a disproportionately large influence over the affairs of their communities. This book reflects that reality. It is about monarchs and their courts; about Parliament-men and religious reformers; and about those who observed and anatomised these worlds, or whose convictions and learning transformed them. The constraints of time and space inevitably make this a highly select cast. I am particularly conscious that I all but ignore, for example, Britain’s great experimental scientists and inventors of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Men such as John Harrison (1693–1776), whose ‘sea clock’ for determining longitude, first successfully tested in 1761, ensured that the Royal George was far less likely to run aground than its French or Spanish rivals. I also have relatively little to say about the lives of ordinary men and women, or the squalor and deprivation that often accompanied them. I take it largely for granted that a society with rudimentary sewerage and welfare systems was disease-ridden and very hard on the poor who made up the vast majority of the population.

Another constant across the period that I do make much of, but which is worth emphasising from the outset, is a matter of simple topography. To the east and west, England and Wales were separated from their neighbours by water. The observation of the Italian philosopher Giovanni Botero in the 1590s holds true throughout the early modern era: ‘In strength of situation no kingdome excelleth England: for it hath these two properties … one is, that it be difficult to besiege; the other, that it be easie to convey in and out all things necessarie: these two commodities hath England by the sea, which to the inhabitants is a deep trench against hostile invasions, and an easie passage to take in or sende out all commodities whatsoever.’2 Here was the starting-point for England’s and, later, Britain’s rulers as they sized up the world beyond their shores.

The aim of this book is first and foremost to provide a clear narrative and explanation of events. With that in mind, I have tried not to fill my canvas with too many figures. Similarly, I have opted for a traditional rendering of places and names – thus Bombay rather than Mumbai; Philip II of Spain, rather than Felipe II, and so on. The most significant exception to this rule has been French kings named Henry, who have been given their native ‘Henri’ in order to distinguish them more clearly from their English counterparts. I have employed the words ‘Britain’ and ‘British’ generously, usually with reference to the Protestants of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, but also as a shorthand for the British and Irish peoples as a collective political unit. ‘The Irish’ I generally reserve for Ireland’s Catholics, whether Gaelic or of Anglo-Norman extraction. There is no single word that accurately denotes the islands of Britain and Ireland as a geographic whole. I have used the phrases ‘the British Isles’, or simply ‘Britain and Ireland’. Neither is entirely satisfactory, but they are preferable to the recently in vogue ‘Atlantic Archipelago’ – a designation that can be claimed, with equal entitlement, by more than two dozen island groups fringing the Atlantic from the Canaries to the Bahamas.

The realm over which successive Tudor, Stuart and Hanoverian monarchs imposed their rule was a composite of many overlapping, and often conflicting, communities. To combine such disparate elements, and then to erect on this shifting base the superstructure of a global empire, would be a fraught and lengthy process. Taking the long view, as I have in this book, has distinct advantages in trying to understand the forces that have shaped modern Britain. Issues and tensions that took centuries to resolve can be traced with a clarity that is sometimes missing when the analysis is confined to a shorter timeframe. A three-centuries viewpoint is particularly revealing of the shifting patterns in Britain’s relations with the rest of Europe, and of the frequent and often substantial impact of European events and ideas on domestic developments. Britain was in many ways an ‘exceptional’ state in the early modern period. But equally it was an integral part of Europe. If the peoples of Britain and Ireland clung more tenaciously to their particular locality than we generally do today, they were also much more likely to see themselves as part of transnational communities of faith and political culture that were centred on the Continent. Many of their greatest exploits during the early modern period – from the Henrician Reformation to the forging of an empire – were undertaken with conscious reference to this European dimension. ‘The utmost rational aim of our Ambition’, declared one Georgian pamphleteer, ‘ought to be, to possess a just Weight, and Consideration in Europe.’3 What follows is an exploration of why, how, and with what success that ambition was pursued.

1

Lost Kingdoms, 1485–1526

But what miserie, what murder, and what execrable plagues this famous region hath suffered by the devision and discencion of the renoumed [sic] houses of Lancastre and Yorke, my witte cannot comprehende nor my toung declare nether yet my penne fully set furthe … All the other discordes, sectes and faccions almoste lively florishe and continue at this presente tyme, to the greate displesure and preiudice of all the christian publike welth. But the olde devided controversie betwene the fornamed families of Lancastre and Yorke, by the union of Matrimony celebrate and consummate betwene the high and mighty Prince Kyng Henry the seventh and the lady Elizabeth his moste worthy Quene, the one beeyng indubitate heire of the hous of Lancastre, and the other of Yorke was suspended and appalled in the person of their moste noble puissant and mighty heire kyng Henry the eight, and by hym clerely buried and perpetually extinct.

Edward Hall, The Union of the Two Noble and Illustre Famelies of

Lancastre [and] Yorke (London, 1548), fo. 1

The men who would be king

On 22 August 1485 the grandson of an obscure Welsh squire seized the throne of England after a brief and relatively bloodless battle. He was a mere twenty-eight years of age, and had spent all of his adult life in exile on the Continent. His invasion force had consisted of a few thousand French and Scottish mercenaries, whose services he had paid for by mortgaging all he owned. And he was acclaimed king on the field of a battle – Bosworth – in which his opponent’s army had outnumbered his own by perhaps two to one. How had Henry Tudor, this unlikely king, this foreigner almost, succeeded? And what does his success tell us about the state of late medieval England, the most powerful territory of his new realm?

An important clue to this seemingly bizarre twist of fate that had put Henry on the throne lies in the manner of Richard III’s defeat. There is much that we do not know about the battle of Bosworth, including where exactly it took place – beyond the fact that it was in the vicinity of the Leicestershire village of Market Bosworth. But one thing is clear: many of Richard’s soldiers either did not fight for him or they switched sides. His headlong charge at Henry’s standard was probably intended to settle the issue quickly before his army disintegrated entirely. In the event, it was the cue for his supposed ally, Sir William Stanley, to bring his sizeable contingent of troops over to Henry’s side. Unable to penetrate the phalanx of French pikemen that protected Henry, the royal guard, surrounded and outnumbered, was cut down. Scorning the opportunity of escape or surrender, Richard was killed ‘fyghting manfully in the thickkest presse of his enemyes’ – the last king of England to perish in battle.1

For Shakespeare, writing over a hundred years later, Bosworth provided a fitting conclusion to Richard III – man and play – and to the Wars of the Roses. ‘The bloody dog is dead …’ declares Henry after killing Richard, supposedly in single combat. ‘Now civil wounds are stopp’d; peace lives again.’2 But in fact the battle resolved very little. The hesitation and treachery that marked many of Richard’s followers at Bosworth were symptomatic of a malaise that had afflicted the English monarchy since the 1450s. Admittedly, Richard had been a peculiarly unpopular king. Even in an age accustomed to over-mighty subjects challenging under-mighty kings, his lèse-majesté following the death of his brother, Edward IV, in 1483 had appeared peculiarly monstrous. For rather than be satisfied with the role of lord protector during his nephew Edward V’s minority, he had seized the young prince and his brother, imprisoned them in the Tower, declared himself king, and had then had them murdered. An uncle killing his nephews, defenceless children, in a naked bid for power was as shocking then as now.

Yet neither Edward V’s fate nor Richard’s was exceptional. The mental and physical feebleness of Henry VI (1421–71), in the context of a deep and prolonged economic recession, and military humiliation abroad, had profoundly weakened the monarchy as an institution. Between 1461 and 1485 the crown had changed hands violently on five occasions – six, if we take the story back to Henry Bolingbroke (the future Henry IV) toppling Richard II in 1399. Nor was there any certainty, in the aftermath of Bosworth Field, that the series of noble revolts, battles and executions for treason that had intermittently convulsed England since 1455 would come to an end any time soon. Not until 1485 did anyone think of these events as part of a single narrative, with Bosworth its final denouement; indeed, the term ‘the Wars of the Roses’ was not popularised until 1829, when it was taken up by the romantic novelist Sir Walter Scott. Henry was fortunate in that Richard III had died without an heir, and that in disposing of the rightful claimants to the throne (the princes in the Tower) he had alienated many of his subjects. But Henry was aware how much he owed to the god of battles, and how weak his title to the crown remained. The vulnerability of the English monarchy by 1485 was plain for all to see, and Bosworth merely raised the question of who was Henry Tudor anyway? To most of his subjects he was merely the latest in a series of royal usurpers, and a largely unknown one at that.