Полная версия:

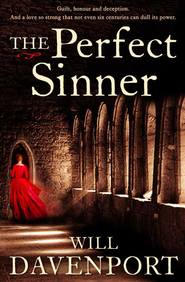

The Perfect Sinner

‘What’s this?’ she asked.

‘I’m doing some restoration,’ Lewis said. ‘It came from the Chantry tower. They want me to put it back together if I can.’

‘Who’s they? English Heritage?’

‘No. The tower’s privately owned. The house and the tower. Don’t you remember? I think it’s changed hands since your time.’

She did remember, vaguely. The great tower had never been an important part of her life in Slapton, having no function.

‘What is this? A memorial of some sort?’

‘Maybe.’

‘Do you know what it says?’

‘Only part of it. You’ve heard of Guy de Bryan?’

‘No.’

He looked surprised for a moment then glanced at his watch yet again. ‘I really should get going. Come back when you’ve got a bit of time. I’ll tell you all about it.’

So then he was gone and she was alone again, outside the quarry, watching him drive away and pushing down the memories which seemed too childish to be allowed. She turned back to the path to Eliza’s, knowing there was no alternative but to walk on down it and knowing that at the far end was the wonderful, dreadful woman who was her grandmother and who loved her and disapproved of her in equal measure.

She sighed and started walking. It had never before struck her as odd that when the path bent around to the left and delivered her, still unprepared, to the house, it was the rear of the house that she saw and not the front. The house sat in a clearing in the trees facing the wrong way, as if it had one day heaved itself up in a sulk and turned its back on its visitors. The garden was here, on this side. The front faced nothing but the dense and ragged trees which Eliza had left untended for years so that they pressed against the front windows, scraping the glass when the wind blew and shading the sitting room. Eliza never bothered to open the curtains. She lived in the kitchen most of the time, except when she was out in her sheds doing obscure jobs with the wrong tools.

Eliza was standing there outside the back door as if she had been expecting her.

‘Have you come by yourself?’ was the first thing she said, taking the shopping bag and peering past Beth at the trees as though she might have to repel an invading horde.

‘Yes,’ said Beth ‘Hello Gran.’

‘You’d better come in before anyone sees you.’

That made Beth look around too, but all was quiet in the clearing in the trees and there was no one there but the two of them.

Eliza’s kitchen was the same as ever. In the middle stood an old oak table and around it were a sofa and three armchairs which, even before they had sagged with half a century of use, had been much too low for the table. Since Beth had first known this room, which was as far back as she could remember, she had always had to lean forward from the swaying nest of springs and horsehair to reach up to the table for her plate or cup. Meals at Quarry Cottage were eaten on your lap, and if Eliza was sitting opposite, you wound up talking to the top of her head because that was all you could see.

‘I’ve got elderflower or mead,’ said Eliza. ‘The mead’s sweeter but the elderflower’s older.’

‘Could I just have a glass of water?’ Beth nearly said mineral water before she remembered where she was.

‘From the tap?’ Eliza sounded shocked. ‘I’d have to boil it.’

‘Oh.’

‘It’s coming out a bit green. The pump’s been greased.’

‘A cup of tea then?’

Eliza went into the larder and came out with two tumblers of a thick amber liquid. Beth recognised the sweet honey smell of her mead and resigned herself. Her grandmother put one on the table and drained most of the other one at a gulp. She was the same as ever, as thin as a kipper, as she always said, and much the same colour. Eliza’s skin was as tough as tanned leather. She looked as if she’d been smoked. Scorning hairdressers after a woman in Dartmouth had once tried to charge her a pound for a cut and wash in the nineteen seventies, she had bought a pair of electric clippers and kept her white hair shorn in a bristly crew cut. She was not much more than five feet two inches tall, but she was not in the slightest bit fragile.

She stood looking down at Beth, who was trying to find a section of the sofa where the ends of the springs weren’t so sharp.

‘You’ve got yourself in a pickle, girl,’ she observed. ‘I never thought going off to London was a good idea. Don’t know what’s wrong with Slapton.’

Eliza didn’t read the papers. She said bad news would come and find you soon enough if it mattered. There wasn’t a radio in the house and Beth was pretty sure her grandmother had never watched television in her entire life.

‘I asked Lewis,’ the old woman said, divining Beth’s puzzlement. ‘They were talking in the churchyard yesterday. I heard your name before they saw me.’

So Lewis knew all about it too.

‘You got thinner,’ Eliza observed, inspecting her.

Thank you.’

‘Don’t thank me. That’s not a compliment. You look like a refugee. Have you been doing what I said? A mug of hot milk every night, with local honey in it? Got to be local. The bees give you what you need, see? The pollen from the flowers around about where you live, that’s the best thing for you.’

There’re not many bees in central London, Gran.’

Eliza snorted. ‘Course there are. There’s bees everywhere. You’re just too busy to notice as well as too busy to eat properly. Well, I suppose I thought you’d be more different.’

‘I haven’t been away that long.’

‘Oh yes you have. Two letters and one postcard in getting on for three years? I suppose I should be counting myself lucky. It’s more than your dad’s had.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Полная версия книги

Всего 10 форматов