Полная версия

Полная версияOn the Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection

I have as yet spoken as if the varieties of the same species were invariably fertile when intercrossed. But it seems to me impossible to resist the evidence of the existence of a certain amount of sterility in the few following cases, which I will briefly abstract. The evidence is at least as good as that from which we believe in the sterility of a multitude of species. The evidence is, also, derived from hostile witnesses, who in all other cases consider fertility and sterility as safe criterions of specific distinction. Gartner kept during several years a dwarf kind of maize with yellow seeds, and a tall variety with red seeds, growing near each other in his garden; and although these plants have separated sexes, they never naturally crossed. He then fertilised thirteen flowers of the one with the pollen of the other; but only a single head produced any seed, and this one head produced only five grains. Manipulation in this case could not have been injurious, as the plants have separated sexes. No one, I believe, has suspected that these varieties of maize are distinct species; and it is important to notice that the hybrid plants thus raised were themselves PERFECTLY fertile; so that even Gartner did not venture to consider the two varieties as specifically distinct.

Girou de Buzareingues crossed three varieties of gourd, which like the maize has separated sexes, and he asserts that their mutual fertilisation is by so much the less easy as their differences are greater. How far these experiments may be trusted, I know not; but the forms experimentised on, are ranked by Sagaret, who mainly founds his classification by the test of infertility, as varieties.

The following case is far more remarkable, and seems at first quite incredible; but it is the result of an astonishing number of experiments made during many years on nine species of Verbascum, by so good an observer and so hostile a witness, as Gartner: namely, that yellow and white varieties of the same species of Verbascum when intercrossed produce less seed, than do either coloured varieties when fertilised with pollen from their own coloured flowers. Moreover, he asserts that when yellow and white varieties of one species are crossed with yellow and white varieties of a DISTINCT species, more seed is produced by the crosses between the same coloured flowers, than between those which are differently coloured. Yet these varieties of Verbascum present no other difference besides the mere colour of the flower; and one variety can sometimes be raised from the seed of the other.

From observations which I have made on certain varieties of hollyhock, I am inclined to suspect that they present analogous facts.

Kolreuter, whose accuracy has been confirmed by every subsequent observer, has proved the remarkable fact, that one variety of the common tobacco is more fertile, when crossed with a widely distinct species, than are the other varieties. He experimentised on five forms, which are commonly reputed to be varieties, and which he tested by the severest trial, namely, by reciprocal crosses, and he found their mongrel offspring perfectly fertile. But one of these five varieties, when used either as father or mother, and crossed with the Nicotiana glutinosa, always yielded hybrids not so sterile as those which were produced from the four other varieties when crossed with N. glutinosa. Hence the reproductive system of this one variety must have been in some manner and in some degree modified.

From these facts; from the great difficulty of ascertaining the infertility of varieties in a state of nature, for a supposed variety if infertile in any degree would generally be ranked as species; from man selecting only external characters in the production of the most distinct domestic varieties, and from not wishing or being able to produce recondite and functional differences in the reproductive system; from these several considerations and facts, I do not think that the very general fertility of varieties can be proved to be of universal occurrence, or to form a fundamental distinction between varieties and species. The general fertility of varieties does not seem to me sufficient to overthrow the view which I have taken with respect to the very general, but not invariable, sterility of first crosses and of hybrids, namely, that it is not a special endowment, but is incidental on slowly acquired modifications, more especially in the reproductive systems of the forms which are crossed.

HYBRIDS AND MONGRELS COMPARED, INDEPENDENTLY OF THEIR FERTILITY.

Independently of the question of fertility, the offspring of species when crossed and of varieties when crossed may be compared in several other respects. Gartner, whose strong wish was to draw a marked line of distinction between species and varieties, could find very few and, as it seems to me, quite unimportant differences between the so-called hybrid offspring of species, and the so-called mongrel offspring of varieties. And, on the other hand, they agree most closely in very many important respects.

I shall here discuss this subject with extreme brevity. The most important distinction is, that in the first generation mongrels are more variable than hybrids; but Gartner admits that hybrids from species which have long been cultivated are often variable in the first generation; and I have myself seen striking instances of this fact. Gartner further admits that hybrids between very closely allied species are more variable than those from very distinct species; and this shows that the difference in the degree of variability graduates away. When mongrels and the more fertile hybrids are propagated for several generations an extreme amount of variability in their offspring is notorious; but some few cases both of hybrids and mongrels long retaining uniformity of character could be given. The variability, however, in the successive generations of mongrels is, perhaps, greater than in hybrids.

This greater variability of mongrels than of hybrids does not seem to me at all surprising. For the parents of mongrels are varieties, and mostly domestic varieties (very few experiments having been tried on natural varieties), and this implies in most cases that there has been recent variability; and therefore we might expect that such variability would often continue and be super-added to that arising from the mere act of crossing. The slight degree of variability in hybrids from the first cross or in the first generation, in contrast with their extreme variability in the succeeding generations, is a curious fact and deserves attention. For it bears on and corroborates the view which I have taken on the cause of ordinary variability; namely, that it is due to the reproductive system being eminently sensitive to any change in the conditions of life, being thus often rendered either impotent or at least incapable of its proper function of producing offspring identical with the parent-form. Now hybrids in the first generation are descended from species (excluding those long cultivated) which have not had their reproductive systems in any way affected, and they are not variable; but hybrids themselves have their reproductive systems seriously affected, and their descendants are highly variable.

But to return to our comparison of mongrels and hybrids: Gartner states that mongrels are more liable than hybrids to revert to either parent-form; but this, if it be true, is certainly only a difference in degree. Gartner further insists that when any two species, although most closely allied to each other, are crossed with a third species, the hybrids are widely different from each other; whereas if two very distinct varieties of one species are crossed with another species, the hybrids do not differ much. But this conclusion, as far as I can make out, is founded on a single experiment; and seems directly opposed to the results of several experiments made by Kolreuter.

These alone are the unimportant differences, which Gartner is able to point out, between hybrid and mongrel plants. On the other hand, the resemblance in mongrels and in hybrids to their respective parents, more especially in hybrids produced from nearly related species, follows according to Gartner the same laws. When two species are crossed, one has sometimes a prepotent power of impressing its likeness on the hybrid; and so I believe it to be with varieties of plants. With animals one variety certainly often has this prepotent power over another variety. Hybrid plants produced from a reciprocal cross, generally resemble each other closely; and so it is with mongrels from a reciprocal cross. Both hybrids and mongrels can be reduced to either pure parent-form, by repeated crosses in successive generations with either parent.

These several remarks are apparently applicable to animals; but the subject is here excessively complicated, partly owing to the existence of secondary sexual characters; but more especially owing to prepotency in transmitting likeness running more strongly in one sex than in the other, both when one species is crossed with another, and when one variety is crossed with another variety. For instance, I think those authors are right, who maintain that the ass has a prepotent power over the horse, so that both the mule and the hinny more resemble the ass than the horse; but that the prepotency runs more strongly in the male-ass than in the female, so that the mule, which is the offspring of the male-ass and mare, is more like an ass, than is the hinny, which is the offspring of the female-ass and stallion.

Much stress has been laid by some authors on the supposed fact, that mongrel animals alone are born closely like one of their parents; but it can be shown that this does sometimes occur with hybrids; yet I grant much less frequently with hybrids than with mongrels. Looking to the cases which I have collected of cross-bred animals closely resembling one parent, the resemblances seem chiefly confined to characters almost monstrous in their nature, and which have suddenly appeared – such as albinism, melanism, deficiency of tail or horns, or additional fingers and toes; and do not relate to characters which have been slowly acquired by selection. Consequently, sudden reversions to the perfect character of either parent would be more likely to occur with mongrels, which are descended from varieties often suddenly produced and semi-monstrous in character, than with hybrids, which are descended from species slowly and naturally produced. On the whole I entirely agree with Dr. Prosper Lucas, who, after arranging an enormous body of facts with respect to animals, comes to the conclusion, that the laws of resemblance of the child to its parents are the same, whether the two parents differ much or little from each other, namely in the union of individuals of the same variety, or of different varieties, or of distinct species.

Laying aside the question of fertility and sterility, in all other respects there seems to be a general and close similarity in the offspring of crossed species, and of crossed varieties. If we look at species as having been specially created, and at varieties as having been produced by secondary laws, this similarity would be an astonishing fact. But it harmonises perfectly with the view that there is no essential distinction between species and varieties.

SUMMARY OF CHAPTER.

First crosses between forms sufficiently distinct to be ranked as species, and their hybrids, are very generally, but not universally, sterile. The sterility is of all degrees, and is often so slight that the two most careful experimentalists who have ever lived, have come to diametrically opposite conclusions in ranking forms by this test. The sterility is innately variable in individuals of the same species, and is eminently susceptible of favourable and unfavourable conditions. The degree of sterility does not strictly follow systematic affinity, but is governed by several curious and complex laws. It is generally different, and sometimes widely different, in reciprocal crosses between the same two species. It is not always equal in degree in a first cross and in the hybrid produced from this cross.

In the same manner as in grafting trees, the capacity of one species or variety to take on another, is incidental on generally unknown differences in their vegetative systems, so in crossing, the greater or less facility of one species to unite with another, is incidental on unknown differences in their reproductive systems. There is no more reason to think that species have been specially endowed with various degrees of sterility to prevent them crossing and blending in nature, than to think that trees have been specially endowed with various and somewhat analogous degrees of difficulty in being grafted together in order to prevent them becoming inarched in our forests.

The sterility of first crosses between pure species, which have their reproductive systems perfect, seems to depend on several circumstances; in some cases largely on the early death of the embryo. The sterility of hybrids, which have their reproductive systems imperfect, and which have had this system and their whole organisation disturbed by being compounded of two distinct species, seems closely allied to that sterility which so frequently affects pure species, when their natural conditions of life have been disturbed. This view is supported by a parallelism of another kind; – namely, that the crossing of forms only slightly different is favourable to the vigour and fertility of their offspring; and that slight changes in the conditions of life are apparently favourable to the vigour and fertility of all organic beings. It is not surprising that the degree of difficulty in uniting two species, and the degree of sterility of their hybrid-offspring should generally correspond, though due to distinct causes; for both depend on the amount of difference of some kind between the species which are crossed. Nor is it surprising that the facility of effecting a first cross, the fertility of the hybrids produced, and the capacity of being grafted together – though this latter capacity evidently depends on widely different circumstances – should all run, to a certain extent, parallel with the systematic affinity of the forms which are subjected to experiment; for systematic affinity attempts to express all kinds of resemblance between all species.

First crosses between forms known to be varieties, or sufficiently alike to be considered as varieties, and their mongrel offspring, are very generally, but not quite universally, fertile. Nor is this nearly general and perfect fertility surprising, when we remember how liable we are to argue in a circle with respect to varieties in a state of nature; and when we remember that the greater number of varieties have been produced under domestication by the selection of mere external differences, and not of differences in the reproductive system. In all other respects, excluding fertility, there is a close general resemblance between hybrids and mongrels. Finally, then, the facts briefly given in this chapter do not seem to me opposed to, but even rather to support the view, that there is no fundamental distinction between species and varieties.

9. ON THE IMPERFECTION OF THE GEOLOGICAL RECORD

On the absence of intermediate varieties at the present day. On the nature of extinct intermediate varieties; on their number. On the vast lapse of time, as inferred from the rate of deposition and of denudation. On the poorness of our palaeontological collections. On the intermittence of geological formations. On the absence of intermediate varieties in any one formation. On the sudden appearance of groups of species. On their sudden appearance in the lowest known fossiliferous strata.

In the sixth chapter I enumerated the chief objections which might be justly urged against the views maintained in this volume. Most of them have now been discussed. One, namely the distinctness of specific forms, and their not being blended together by innumerable transitional links, is a very obvious difficulty. I assigned reasons why such links do not commonly occur at the present day, under the circumstances apparently most favourable for their presence, namely on an extensive and continuous area with graduated physical conditions. I endeavoured to show, that the life of each species depends in a more important manner on the presence of other already defined organic forms, than on climate; and, therefore, that the really governing conditions of life do not graduate away quite insensibly like heat or moisture. I endeavoured, also, to show that intermediate varieties, from existing in lesser numbers than the forms which they connect, will generally be beaten out and exterminated during the course of further modification and improvement. The main cause, however, of innumerable intermediate links not now occurring everywhere throughout nature depends on the very process of natural selection, through which new varieties continually take the places of and exterminate their parent-forms. But just in proportion as this process of extermination has acted on an enormous scale, so must the number of intermediate varieties, which have formerly existed on the earth, be truly enormous. Why then is not every geological formation and every stratum full of such intermediate links? Geology assuredly does not reveal any such finely graduated organic chain; and this, perhaps, is the most obvious and gravest objection which can be urged against my theory. The explanation lies, as I believe, in the extreme imperfection of the geological record.

In the first place it should always be borne in mind what sort of intermediate forms must, on my theory, have formerly existed. I have found it difficult, when looking at any two species, to avoid picturing to myself, forms DIRECTLY intermediate between them. But this is a wholly false view; we should always look for forms intermediate between each species and a common but unknown progenitor; and the progenitor will generally have differed in some respects from all its modified descendants. To give a simple illustration: the fantail and pouter pigeons have both descended from the rock-pigeon; if we possessed all the intermediate varieties which have ever existed, we should have an extremely close series between both and the rock-pigeon; but we should have no varieties directly intermediate between the fantail and pouter; none, for instance, combining a tail somewhat expanded with a crop somewhat enlarged, the characteristic features of these two breeds. These two breeds, moreover, have become so much modified, that if we had no historical or indirect evidence regarding their origin, it would not have been possible to have determined from a mere comparison of their structure with that of the rock-pigeon, whether they had descended from this species or from some other allied species, such as C. oenas.

So with natural species, if we look to forms very distinct, for instance to the horse and tapir, we have no reason to suppose that links ever existed directly intermediate between them, but between each and an unknown common parent. The common parent will have had in its whole organisation much general resemblance to the tapir and to the horse; but in some points of structure may have differed considerably from both, even perhaps more than they differ from each other. Hence in all such cases, we should be unable to recognise the parent-form of any two or more species, even if we closely compared the structure of the parent with that of its modified descendants, unless at the same time we had a nearly perfect chain of the intermediate links.

It is just possible by my theory, that one of two living forms might have descended from the other; for instance, a horse from a tapir; and in this case DIRECT intermediate links will have existed between them. But such a case would imply that one form had remained for a very long period unaltered, whilst its descendants had undergone a vast amount of change; and the principle of competition between organism and organism, between child and parent, will render this a very rare event; for in all cases the new and improved forms of life will tend to supplant the old and unimproved forms.

By the theory of natural selection all living species have been connected with the parent-species of each genus, by differences not greater than we see between the varieties of the same species at the present day; and these parent-species, now generally extinct, have in their turn been similarly connected with more ancient species; and so on backwards, always converging to the common ancestor of each great class. So that the number of intermediate and transitional links, between all living and extinct species, must have been inconceivably great. But assuredly, if this theory be true, such have lived upon this earth.

ON THE LAPSE OF TIME.

Independently of our not finding fossil remains of such infinitely numerous connecting links, it may be objected, that time will not have sufficed for so great an amount of organic change, all changes having been effected very slowly through natural selection. It is hardly possible for me even to recall to the reader, who may not be a practical geologist, the facts leading the mind feebly to comprehend the lapse of time. He who can read Sir Charles Lyell's grand work on the Principles of Geology, which the future historian will recognise as having produced a revolution in natural science, yet does not admit how incomprehensibly vast have been the past periods of time, may at once close this volume. Not that it suffices to study the Principles of Geology, or to read special treatises by different observers on separate formations, and to mark how each author attempts to give an inadequate idea of the duration of each formation or even each stratum. A man must for years examine for himself great piles of superimposed strata, and watch the sea at work grinding down old rocks and making fresh sediment, before he can hope to comprehend anything of the lapse of time, the monuments of which we see around us.

It is good to wander along lines of sea-coast, when formed of moderately hard rocks, and mark the process of degradation. The tides in most cases reach the cliffs only for a short time twice a day, and the waves eat into them only when they are charged with sand or pebbles; for there is reason to believe that pure water can effect little or nothing in wearing away rock. At last the base of the cliff is undermined, huge fragments fall down, and these remaining fixed, have to be worn away, atom by atom, until reduced in size they can be rolled about by the waves, and then are more quickly ground into pebbles, sand, or mud. But how often do we see along the bases of retreating cliffs rounded boulders, all thickly clothed by marine productions, showing how little they are abraded and how seldom they are rolled about! Moreover, if we follow for a few miles any line of rocky cliff, which is undergoing degradation, we find that it is only here and there, along a short length or round a promontory, that the cliffs are at the present time suffering. The appearance of the surface and the vegetation show that elsewhere years have elapsed since the waters washed their base.

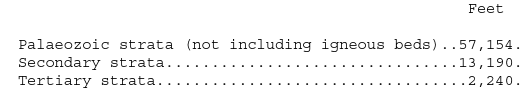

He who most closely studies the action of the sea on our shores, will, I believe, be most deeply impressed with the slowness with which rocky coasts are worn away. The observations on this head by Hugh Miller, and by that excellent observer Mr. Smith of Jordan Hill, are most impressive. With the mind thus impressed, let any one examine beds of conglomerate many thousand feet in thickness, which, though probably formed at a quicker rate than many other deposits, yet, from being formed of worn and rounded pebbles, each of which bears the stamp of time, are good to show how slowly the mass has been accumulated. Let him remember Lyell's profound remark, that the thickness and extent of sedimentary formations are the result and measure of the degradation which the earth's crust has elsewhere suffered. And what an amount of degradation is implied by the sedimentary deposits of many countries! Professor Ramsay has given me the maximum thickness, in most cases from actual measurement, in a few cases from estimate, of each formation in different parts of Great Britain; and this is the result: —

– making altogether 72,584 feet; that is, very nearly thirteen and three-quarters British miles. Some of these formations, which are represented in England by thin beds, are thousands of feet in thickness on the Continent. Moreover, between each successive formation, we have, in the opinion of most geologists, enormously long blank periods. So that the lofty pile of sedimentary rocks in Britain, gives but an inadequate idea of the time which has elapsed during their accumulation; yet what time this must have consumed! Good observers have estimated that sediment is deposited by the great Mississippi river at the rate of only 600 feet in a hundred thousand years. This estimate may be quite erroneous; yet, considering over what wide spaces very fine sediment is transported by the currents of the sea, the process of accumulation in any one area must be extremely slow.