Полная версия

Полная версияNotes on the Floridian Peninsula; its Literary History, Indian Tribes and Antiquities

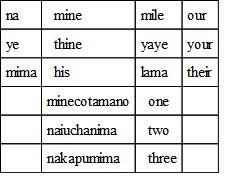

Without altogether differing from the learned abbé in his position, for it savors strongly of truth, it might be well, with what material we have at hand, to see whether other analogies could be discovered. The pronominal adjectives and the first three numerals are as follows;—

Now, bearing in mind that the pronouns of the first and second persons and the numerals are primitive words, and that in American philology it is a rule almost without exception that personal pronouns and pronominal adjectives are identical in their consonants,241 we have five primitive words before us. On comparing them with other aboriginal tongues, the n of the first person singular is found common to the Algonquin Lenape family, but in all other points they are such contrasts that this must pass for an accidental similarity. A resemblance may be detected between the Uchee nowah, two, nokah, three, and naiucha-mima, naka-pumima. Taken together, iti-na, my father, sounds not unlike the Cherokee etawta, and Adelung notices the slight difference there is between niha, eldest brother, and the Illinois nika, my brother. But these are trifling compared to the affinities to the Carib, and I should not be astonished if a comparison of Pareja with Gilü and D’Orbigny placed beyond doubt its relationship to this family of languages. Should this brief notice give rise to such an investigation, my object in inserting it will have been accomplished.

The French voyagers occasionally noted down a word or two of the tongues they encountered, and indeed Laudonniére assures us that he could understand the greater part of what they said. Such were tapagu tapola, little baskets of corn, sieroa pira, red metal, antipola bonnasson, a term of welcome meaning, brother, friend, or something of that sort (qui vaut autant à dire comme frère, amy, ou chose semblable).242 Albert Gallatin243 subjected these to a critical examination, but deciphered none except the last. This he derives from the Choktah itapola, allies, literally, they help each other, while “in Muskohgee, inhisse, is, his friends, and ponhisse, our friends,” which seems a satisfactory solution. It was used as a friendly greeting both at the mouth of the St. Johns and thirty leagues north of that river; but this does not necessarily prove the natives of those localities belonged to the Chahta family, as an expression of this sort would naturally gain wide prevalence among very diverse tribes.

Fontanedo has also preserved some words of the more southern languages, but none of much importance.

CHAPTER IV.

LATER TRIBES

§ 1. Yemassees.—Uchees.—Apalachicolos.—Migrations northward.

§ 2. Seminoles.

§ 1.—Yemassees and other Tribes

About the close of the seventeenth century, when the tribes who originally possessed the peninsula had become dismembered and reduced by prolonged conflicts with the whites and between themselves, various bands from the more northern regions, driven from their ancestral homes partly by the English and partly by a spirit of restlessness, sought to fix their habitations in various parts of Florida.

The earliest of these were the Savannahs or Yemassees (Yammassees, Jamasees, Eamuses,) a branch of the Muskogeh or Creek nation, who originally inhabited the shores of the Savannah river and the low country of Carolina. Here they generally maintained friendly relations with the Spanish, who at one period established missions among them, until the arrival of the English. These purchased their land, won their friendship, and embittered them against their former friends. As the colony extended, they gradually migrated southward, obtaining a home by wresting from their red and white possessors the islands and mainland along the coast of Georgia and Florida. The most disastrous of these inroads was in 1686, when they drove the Spanish colonists from all the islands north of the St. Johns, and laid waste the missions and plantations that had been commenced upon them. Subsequently, spreading over the savannas of Alachua and the fertile plains of Middle Florida, they conjoined with the fragments of older nations to form separate tribes, as the Chias, Canaake, Tomocos or Atimucas, and others. Of these the last-mentioned were the most important. They dwelt between the St. Johns and the Suwannee, and possessed the towns of Jurlo Noca, Alachua, Nuvoalla, and others. At the devastation of their settlements by the English and Creeks in 1704, 1705 and 1706, they removed to the shores of Musquito Lagoon, sixty-five miles south of St. Augustine, where they had a village, long known as the Pueblo de Atimucas.

A portion of the tribe remained in Carolina, dwelling on Port Royal Island, whence they made frequent attacks on the Christian Indians of Florida, carrying them into captivity, and selling them to the English. In April, 1715, however, instigated as was supposed by the Spanish, they made a sudden attack on the neighboring settlements, but were repulsed and driven from the country. They hastened to St. Augustine, “where they were received with bells ringing and guns firing,”244 and given a spot of ground within a mile of the city. Here they resided till the attack of Colonel Palmer in 1727, who burnt their village and destroyed most of its inhabitants. Some, however, escaped, and to the number of twenty men, lived in St. Augustine about the middle of the century. Finally, this last miserable remnant was enslaved by the Seminoles, and sunk in the Ocklawaha branch of that tribe.245

Originating from near the same spot as the Yemassees were the Uchees. When first encountered by the whites, they possessed the country on the Carolina side of the Savannah river for more than one hundred and fifty miles, commencing sixty miles from its mouth, and, consequently, just west of the Yemassees. Closely associated with them here, were the Palachoclas or Apalachicolos. About the year 1716, nearly all the latter, together with a portion of the Uchees, removed to the south under the guidance of Cherokee Leechee, their chief, and located on the banks of the stream called by the English the Flint river, but which subsequently received the name of Apalachicola.

The rest of the Uchees clung tenaciously to their ancestral seats in spite of the threats and persuasion of the English, till after the middle of the century, when a second and complete migration took place. Instead of joining their kinsmen, however, they kept more to the east, occupying sites first on the head-waters of the Altamaha, then on the Santilla, (St. Tillis,) St. Marys, and St. Johns, where we hear of them as early as 1786. At the cession to the United States, (1821,) they had a village ten miles south of Volusia, near Spring Gardens. At this period, though intermarrying with their neighbors, they still maintained their identity, and when, at the close of the Seminole war in 1845, two hundred and fifty Indians embarked at Tampa for New Orleans and the West, it is said a number of them belonged to this tribe, and probably constituted the last of the race.246

Both on the Apalachicola and Savannah rivers this tribe was remarkable for its unusually agricultural and civilized habits, though of a tricky and dishonest character. Bartram247 gives the following description of their town of Chata on the Chatauchee:—“It is the most compact and best situated Indian town I ever saw; the habitations are large and neatly built; the walls of the houses are constructed of a wooden frame, then lathed and plastered inside and out, with a reddish, well-tempered clay or mortar, which gives them the appearance of red brick walls, and these houses are neatly covered or roofed with cypress bark or shingles of that tree.” This, together with the Savanuca town on the Tallapoosa or Oakfuske river, comprised the whole of the tribe at that time resident in this vicinity.

Their language was called the Savanuca tongue, from the town of that name. It was peculiar to themselves and radically different from the Creek tongue or Lingo, by which they were surrounded; “It seems,” says Bartram, “to be a more northern tongue;” by which he probably means it sounded harsher to the ear. It was said to be a dialect of the Shawanese, but a comparison of the vocabularies indicates no connection, and it appears more probable that it stands quite alone in the philology of that part of the continent.

While these movements were taking place from the north toward the south, there were also others in a contrary direction. One of the principal of these occurred while Francisco de la Guerra was Governor-General of Florida, (1684-1690,) in consequence of an attempt made by Don Juan Marquez to remove the natives to the West India islands and enslave them. We have no certain knowledge how extensive it was, though it seems to have left quite a number of missions deserted.248

What has excited more general attention is the tradition of the Shawnees, (Shawanees, Sawannees, Shawanos,) that they originally came from the Suwannee river in Florida, whose name has been said to be “a corruption of Shawanese,” and that they were driven thence by the Cherokees.249 That such was the origin of the name is quite false, as its present appellation is merely a corruption of the Spanish San Juan, the river having been called the Little San Juan, in contradistinction to the St. Johns, (el rio de San Juan,) on the eastern coast.250 Nor did they ever live in this region, but were scions of the Savannah stem of the Creeks, accolents of the river of that name, and consequently were kinsmen of the Yemassees.

§ 2.—The Seminoles

The Creek nation, so called says Adair from the number of streams that intersected the lowlands they inhabited, more properly Muskogeh, (corrupted into Muscows,) sometimes Western Indians, as they were supposed to have come later than the Uchees,251 and on the early maps Cowetas (Couitias,) and Allibamons from their chief towns, was the last of those waves of migration which poured across the Mississippi for several centuries prior to Columbus. Their hunting grounds at one period embraced a vast extent of country reaching from the Atlantic coast almost to the Mississippi. After the settlement of the English among them, they diminished very rapidly from various causes, principally wars and the ravages of the smallpox, till about 1740 the whole number of their warriors did not exceed fifteen hundred. The majority of these belonged to that branch of the nation, called from its more southern position the Lower Creeks, of mongrel origin, made up of the fragments of numerous reduced and broken tribes, dwelling north and northwest of the Floridian peninsula.252

When Governor Moore of South Carolina made his attack on St. Augustine, he included in his complement a considerable band of this nation. After he had been repulsed they kept possession of all the land north of the St. Johns, and, uniting with certain negroes from the English and Spanish colonies, formed the nucleus of the nation, subsequently called Ishti semoli, wild men,253 corrupted into Seminolies and Seminoles, who subsequently possessed themselves of the whole peninsula and still remain there. Others were introduced by the English in their subsequent invasions, by Governor Moore, by Col. Palmer, and by General Oglethorpe. As early as 1732, they had founded the town of Coweta on the Flint river, and laid claim to all the country from there to St. Augustine.254 They soon began to make incursions independent of the whites, as that led by Toonahowi in 1741, as that which in 1750, under the guidance of Secoffee, forsook the banks of the Apalachicola, and settled the fertile savannas of Alachua, and as the band that in 1808 followed Micco Hadjo to the vicinity of Tallahassie. They divided themselves into seven independent bands, the Latchivue or Latchione, inhabiting the level banks of the St. Johns, and the sand hills to the west, near the ancient fort Poppa, (San Francisco de Pappa,) opposite Picolati, the Oklevuaha, or Oklewaha on the river that bears their name, the Chokechatti, the Pyaklekaha, the Talehouyana or Fatehennyaha, the Topkelake, and a seventh, whose name I cannot find.

According to a writer in 1791,255 they lived in a state of frightful barbarity and indigence, and were “poor and miserable beyond description.” When the mother was burdened with too many children, she hesitated not to strangle the new-born infant, without remorse for her cruelty or odium among her companions. This is the only instance that I have ever met in the history of the American Indians where infanticide was in vogue for these reasons, and it gives us a fearfully low idea of the social and moral condition of those induced by indolence to resort to it. Yet other and by far the majority of writers give us a very different opinion, assure us that they built comfortable houses of logs, made a good, well-baked article of pottery, raised plenteous crops of corn, beans, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, tobacco, swamp and upland rice, peas, melons and squashes, while in an emergency the potatoe-like roots of the china brier or red coonta, the tap root of the white coonta,256 the not unpleasant cabbage of the palma royal and palmetto, and the abundant game and fish, would keep at a distance all real want.257

As may readily be supposed from their vagrant and unsettled mode of life, their religious ideas were very simple. Their notion of a God was vague and ill-defined; they celebrated certain festivals at corn planting and harvest; they had a superstition regarding the transmigration of souls and for this purpose held the infant over the face of the dying mother;258 and from their great reluctance to divulge their real names, it is probable they believed in a personal guardian spirit, through fear of offending whom a like hesitation prevailed among other Indian tribes, as well as among the ancient Romans, and, strange to say, is in force to this day among the lower class of Italians.259 They usually interred the dead, and carefully concealed the grave for fear it should be plundered and desecrated by enemies, though at other times, as after a battle, they piled the slain indiscriminately together, and heaped over them a mound of earth. One instance is recorded260 where a female slave of a deceased princess was decapitated on her tomb to be her companion and servant on the journey to the land of the dead.

A comparison of the Seminole with the Muskogeh vocabulary affords a most instructive lesson to the philologist. With such rapidity did the former undergo a vital change that as early as 1791 “it was hardly understood by the Upper Creeks.”261 The later changes are still more marked and can be readily studied as we have quite a number of vocabularies preserved by different writers.

Ever since the first settlement of these Indians in Florida they have been engaged in a strife with the whites,262 sometimes desultory and partial, but usually bitter, general, and barbarous beyond precedent in the bloody annals of border warfare. In the unanimous judgment of unprejudiced writers, the whites have ever been in the wrong, have ever enraged the Indians by wanton and unprovoked outrages, but they have likewise ever been the superior and victorious party. The particulars of these contests have formed the subjects of separate histories by able writers, and consequently do not form a part of the present work.

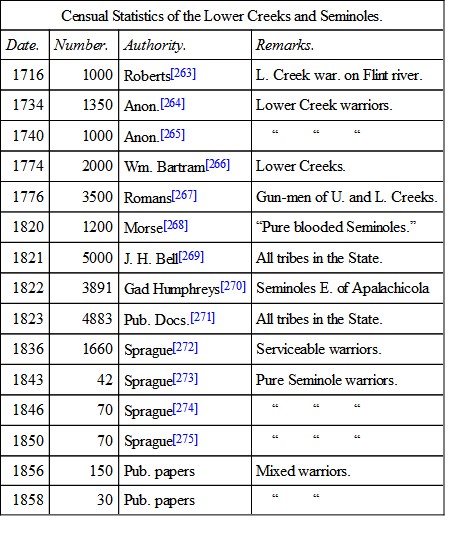

Without attempting a more minute specification, it will be sufficient to point out the swift and steady decrease of this and associated tribes by a tabular arrangement of such censual statistics as appear most worthy of trust.

[263] Roberts, First Disc. of Fla., p. 90.

[264] Collections of Georgia Hist. Soc. Vol. II., p. 318.

[265] Ibid., p. 73.

[266] Travels, p. 211.

[267] Nat. History, p. 91.

[268] Report on Indian Affairs, p. 33.

[269] Cohen, Notices of Florida, p. 48.

[270] Sprague, Hist. of the Fla. War, p. 19.

[271] American State Papers, Vol. VI., p. 439.

[272] Hist. of the Fla. War, p. 97.

[273] Ibid., p. 409.

[274] Ibid., p. 512.

[275] Ibid.

Probably within the present year (1859) the last of this nation, the only free representatives of those many tribes east of the Mississippi that two centuries since held undisturbed sway, will bid an eternal farewell to their ancient abodes, and leave them to the quiet possession of that race that seems destined to supplant them.

CHAPTER V.

THE SPANISH MISSIONS

Early Attempts.—Efforts of Aviles.—Later Missions.—Extent during the most flourishing period.—Decay.

It was ever the characteristic of the Spanish conqueror that first in his thoughts and aims was the extension of the religion in which he was born and bred. The complete history of the Romish Church in America would embrace the whole conquest and settlement of those portions held originally by France and Spain. The earliest and most energetic explorers of the New and much of the Old World have been the pious priests and lay brethren of this religion. While others sought gold they labored for souls, and in all the perils and sufferings of long journeys and tedious voyages cheerfully bore a part, well rewarded by one convert or a single baptism. With the same zeal that distinguished them everywhere else did they labor in the unfruitful vineyard of Florida, and as the story of their endeavors is inseparably bound up with the condition of the natives and progress of the Spanish arms, it is with peculiar fitness that the noble toils of these self-denying men become the theme of our investigation.

The earliest explorers, De Leon, Narvaez, and De Soto, took pains to have with them devout priests as well as bold lancers, and remembered, which cannot be said of all their cotemporaries, that though the natives might possess gold, they were not devoid of souls. The latter included in his complement no less than twelve priests, eight lay brethren, and four clergymen of inferior rank; but their endeavors seem to have achieved only a very paltry and transient success.

The first wholly missionary voyage to the coast of Florida, and indeed to any part of America north of Mexico, was undertaken by Luis Cancel de Balbastro, a Dominican friar, who in 1547 petitioned Charles I. of Spain to fit out an armament for converting the heathen of that country. A gracious ear was lent to his proposal, and two years afterwards, in the spring of 1549, a vessel set sail from the port of Vera Cruz in Mexico, commanded by the skillful pilot Juan de Arana, and bearing to their pious duty Luis Cancel with three other equally zealous brethren, Juan Garcia, Diego de Tolosa, and Gregorio Beteta. Their story is brief and sad. Going by way of Havana they first struck the western coast of the peninsula about 28° north latitude the day after Ascension day. After two months wasted in fruitless efforts to conciliate the natives in various parts, when all but Beteta had fallen martyrs to their devotion to the cause of Christianity, the vessel put back from her bootless voyage, and returned to Vera Cruz.263

Some years afterwards (1559), when Don Tristan de Luna y Arellano founded the colony of Santa Maria de Felipina near where Pensacola was subsequently built, he was accompanied by a provincial bishop and a considerable corps of priests, but as his attempt was unsuccessful and his colony soon disbanded, they could have made no impression on the natives.264

It was not till the establishment of a permanent garrison at St. Augustine by the Adelantado Pedro Menendez de Aviles, that the Catholic religion took firm root in Floridian soil. In the terms of his outfit is enumerated the enrollment of four Jesuit priests and twelve lay brethren. Everywhere he displayed the utmost energy in the cause of religion; wherever he placed a garrison, there was also a spiritual father stationed. In 1567 he sent the two learned and zealous missionaries Rogel and Villareal to the Caloosas, among whom a settlement had already been formed under Francescso de Reinoso. At their suggestion a seminary for the more complete instruction of youthful converts was established at Havana, to which among others the son of the head chief was sent, with what success we have previously seen.

The following year ten other missionaries arrived, one of whom, Jean Babtista Segura, had been appointed Vice Provincial. The majority of these worked with small profit in the southern provinces, but Padre Antonio Sedeño settled in the island of Guale,265 and is to be remembered as the first who drew up a grammar and catechism of any aboriginal tongue north of Mexico; but he reaped a sparse harvest from his toil; for though five others labored with him, we hear of only seven conversions, and four of these infants in articulo mortis. Yet it is also stated that as early as 1566 the Adelantado himself had brought about the conversion of these Indians en masse. A drought of eight months had reduced them to the verge of starvation. By his advice a large cross was erected and public prayer held. A tremendous storm shortly set in, proving abundantly to the savages the truth of his teachings. But they seem to have turned afresh to their wallowing in the mire.

In 1569, the Padre Rogel gave up in despair the still more intractable Caloosas; and among the more cultivated nations surrounding San Felipe, north of the Savannah river, sought a happier field for his efforts. In six months he had learned the language and at first flattered himself much on their aptness for religious instruction. But in the fall, when the acorns ripened, all his converts hastened to decamp, leaving the good father alone in his church. And though he followed them untiringly into woods and swamps, yet “with incredible wickedness they would learn nothing, nor listen to his exhortations, but rather ridiculed them, jeopardizing daily more and more their salvation.” With infinite pains he collected some few into a village, gave them many gifts, and furnished them food and mattocks; but again they most ungratefully deserted him “with no other motive than their natural laziness and fickleness.” Finding his best efforts thrown away on such stiff-necked heathen, with a heavy heart he tore down his house and church, and, shaking the dust off his feet, quitted the country entirely.

At this period the Spanish settlements consisted of three colonies: St. Augustine, originally built south of where it now stands on St. Nicholas creek, and changed in 1566, San Matteo at the mouth of the river of the same name, now the St. Johns,266 and fifty leagues north of this San Felipe in the province of Orista or Santa Helena, now South Carolina. In addition to these there were five block-houses, (casas fuertes), two, Tocobaga and Carlos, on the western coast, one at its southern extremity, Tegesta, one in the province of Ais or Santa Lucea, and a fifth, which Juan Pardo had founded one hundred and fifty leagues inland at the foot of certain lofty mountains, where a cacique Coava ruled the large province Axacàn.267 There seem also to have been several minor settlements on the St. Johns.

Such was the flourishing condition of the country when that “terrible heretic and runaway galley slave,” as the Spanish chronicler calls him, Dominique de Gourgues of Mont Marsain, aided by Pierre le Breu, who had escaped the massacre of the French in 1565, and the potent chief Soturiba, demolished the most important posts (1567). Writers have over-rated the injury this foray did the colony. In reality it served but to stimulate the indomitable energy of Aviles. Though he himself was at the court of Spain and obliged to remain there, with the greatest promptness he dispatched Estevan de las Alas with two hundred and seventy-three men, who rebuilt and equipped San Matheo, and with one hundred and fifty of his force quartered himself in San Felipe.

With him had gone out quite a number of priests. The majority of these set out for the province of Axacàn, under the guidance of the brother of its chief, who had been taken by Aviles to Spain, and there baptized, in honor of the viceroy of New Spain, Don Luis de Velasco. His conversion, however, was only simulation, as no sooner did he see the company entirely remote from assistance, than, with the aid of some other natives, he butchered them all, except one boy, who escaped and returned to San Felipe. Three years after (1569), the Adelantado made an attempt to revenge this murder, but the perpetrators escaped him.