Полная версия:

The Frozen River

The government rate was 25 rupees a day per horse.

4 horses @ 25 rupees a day = 100 rupees a day for 14 days = 1,400 Rs

2 men @ 10 rupees a day with double allowance for the cold = 280 Rs

Grand total = 1,680 Rs

I paid them an advance. Their wives watched intently as the men counted the money and then handed it over to them. The men now had to get the horses shod and fed with barley. We would leave the next day in the afternoon.

A grave situation

In between these negotiations I went to find two graves in a willow grove at the back of the village. The teacher had tipped me off. The first was an army officer’s, a fine sarcophagus:

IN EVER LOVING MEMORY OF HERBERT W. CHRISTIAN

CAPTAIN KING’S ROYAL RIFLES FIFTH SON OF GEORGE AND MARY CHRISTIAN BIGHTON WOOD ALRESFORD ENGLAND DIED OF FEVER AT SURU MAY 21ST 1896 AGED 29

A corner of a foreign land that was forever Hampshire, with magnificent views of the Nun Kun massif. His regiment, the 60th Rifles, had been involved in the Relief of Chitral, a small beleaguered fortress right up on the Afghan border. He had used his leave to hunt ibex and markhor.

The other grave was that of a Ladakhi Christian, his name carved on a slate slab about eighteen inches square. Simple and minimalist.

IN LOVING MEMORY

OF SC GERGAN

LEH LADAKH BORN

29 12 1900 KILLED

BY KUTH RAIDERS

AT PENTSE LA AGED 29 ON

14. 6. 1929 WHILE ON DUTY

Both men, I noticed, were twenty-nine when they died. I had no intention of joining them just yet. As I was only twenty-two, it gave me seven years’ grace.

The Gergans were well known. Back down in Srinagar in Sonwar bazaar I had met Sonam Skyabldan Gergan, Chimed Gergan’s brother, and he told me the story. Chimed had been a forest and game officer for the Maharajah of Jammu and Kashmir. The previous summer he had apprehended some Kishtwari smugglers of kuth, a valuable plant found on the Pense La. Kuth had a high value as it was used as a drug, dye and medicine. Gergan confiscated their haul and took them down to Kargil to see the magistrate as they had evaded customs duties, but they managed to bribe their way out of trouble. The next year they were not afraid of Gergan, so when he tried to re-arrest them they simply knifed him, left him on the pass to die and fled back to Kishtwar.

After this tragic death, Sonam Skyabldan Gergan was given his brother’s job and was able to check up on all his father’s historical observations about the history of Ladakh. His father, Joseph Gergan, had helped translate the Bible into Ladakhi for the Moravian missionaries. When I told Mr Gergan that I was going to Zangskar for the winter he looked at me quizzically and simply said, ‘Is that wise?’

Snuff and silver horse bell

In the mountains you were always judged by the amount of baggage you had and the number of pack animals. In the summer some caravans had a hundred horses. That was very respectable. A large caravan on the move had a wonderful rhythm and life all of its own. Now my own small caravan from Suru was made up of two horsemen and four horses. So in the eyes of the village I was only a four-horse wallah.

Loading was simple. First, rough horse blankets were slung over the backs of the horses to cushion the load and prevent chafing sores, then homemade wooden pack saddles were secured in place. Next, the girth strap, which was only two strands of rope, was tightened several times. While this was going on, the packhorses were given nosebags full of barley and chaff. Loading all the horses took at least half an hour each morning, often before dawn when your fingers were at their coldest. You got going as quickly as possible.

Each load was carefully organised, weighed and balanced. Each day the horses had the same load, and if the load slipped at any point on the journey they simply stopped and waited for the two horsemen to readjust and tighten the load. Everyone knew what they were doing. It was often far too cold to talk.

Day one. We set out in the middle of the afternoon and began to walk towards the fine snow-capped pyramid of Nun, which at 23,500ft was the highest peak for many miles. An elegant curved plume of spindrift was blowing off the summit, the speed of the jet stream probably in excess of 100 mph, icy winds that sooner or later would come down to the valley floor.

As we walked along the path beneath the mountain there was complete silence. The streams were all frozen – just the odd gurgle coming from beneath the ice. Icicles hung down from overhangs, cliffs and crevices. The road had its own path and we simply followed, not speaking a word. We knew the risks. We were just glad to get going and bask in what was left of the afternoon sunshine.

The Nun Kun massif towered above us, a wonderfully cosmopolitan mountain group that attracted climbers of many different nationalities: British and Nepalese as well as American, Italian, French and Swiss. These mountains were worshipped by the local villagers, who thought that foreign mountaineers were climbing to find God. Why else go to those lengths or heights? Maybe they were right. God was always over the next ridge. But then if there were many mountains, surely there must be many gods, not just one?

The packhorses moved in line ahead slowly but surely, pacing along the unmade road. On dried-up river beds small mushrooms of dust emanated from their hooves. Occasionally they jockeyed for position, but often they were content to go at their own measured pace. Very soon the rhythm of the caravan took hold of us and we settled down, as all caravans do. The sort of pace you could keep up for weeks on end.

In front was Fazal Din with the leading rein. He smoked cigarettes through a clenched fist. He took a deep breath every few paces and was almost in a trance. The other horseman, Jamal Din, at the rear, chewed naswar, Afghan snuff, and every so often exuded a long jet of green spittle that congealed in the dust.17 In the Hindu Kush I had seen the effect of opium on porters. It delayed their progress by hours, even days, as they slowly lost track of time or where they were going. Every man has his poison.

I can still smell the caravan, an earthy, pungent smell that reeks of warm horse, sweat, leather and straining muscles. Even in sub-zero temperatures it had a certain je ne sais quoi – a musky stable odour of horse dung with a bit of hay and fodder thrown in for good measure. Eau de cheval. Wolves would have picked the scent up many miles away on the cold wind and licked their lips.

The packhorses stood patiently every morning, waiting to be loaded. Three were brown or bay – the fourth was black. They all had a white blaze on their foreheads, a makeshift bridle and leading rein. They say that Zangskari horses are some of the toughest in the world, second only to Yarkandi horses. They can carry loads and even people over the main Karakoram Pass at over 18,000ft, and the Indian army often used them for the resupply of troops at high altitude.

The relief of walking was enormous. And then out of the silence came the sound of a bell approaching us. Clear and insistent – a silver horse bell. The horse was ridden at a trot by a red lama. Over the saddle was an ornate Tibetan saddle rug with dragons and snow lions. An imposing man with a broad, bronzed face and good stirrups. A fine and inspiring sight. The lama passed without a word, but smiled and raised his hand. It was as if he were in meditation. These mountains have that effect on you without you even thinking.

The sound of the bell was so clear that it stayed with me for several hours. The pace of the horse and demeanour of the rider were so very different to ours. He was probably a monastery manager making his way back to Leh before the snows came. Just a silver horse bell, and yet the space within which it rang seemed so vast.

Parkachik glacier

Sleeping outside was positively parky, -15°C, sometimes -20°C. First night, a field beyond Parkachik. I sheltered behind the hampers. Making tea was not easy as water had to be gleaned from small streams that only flowed under the ice for a few hours a day. The ice axe came into its own.

All during that first night, as I lay on the frozen earth, I could hear the glacier creaking and groaning to itself as it slowly crept down the slopes of Nun Kun towards the cold green waters of the Suru river. The Parkachik glacier is over eight miles long and sounded like some wild animal turning over in its sleep, stretching and yawning. A wild beast that fed off avalanches. Its snout came right down into the water.

Day two. We set off before dawn. A crescent moon, pale amid the stars. I watched as a 100ft pinnacle of ice hovered, teetered and then toppled into the water in slow motion. Hardly a splash, just a ripple reaching out. The glacier once came right across the river. In the past this was the beginning of Buddhist territory and grazing rights. Somewhere nearby there was a rock inscription in Tibetan that demarcated the boundary of Rangdom. Invisible boundaries of influence and ideas. It was difficult to tell where autumn ended and winter began. Fluid frontiers.

The Suru river was clear, green and sedate. Ice floes from the glacier were joined by thousands of other smaller ones from upstream. A continuous process, and fascinating to watch. Ice in another dimension, like ice ferns but on a vast scale. The freezing-up of a large Himalayan river was a long and tedious process that took many months. Yet few people witnessed it. Sometimes great sheets of ice formed in the shallows and froze over. But the river level often changed. If the sun shone for a day or two, the glaciers would melt a bit and the river would rise, and if it was very cold the side streams froze up and the river level fell. The ice sheets would then collapse, break up and flow downstream. A continuous process of ice forming and breaking, ice being carried downstream. Hundreds of ice floes were on the move. A dignified procession. And the green of the river not dissimilar to the one green pane of glass in my room, only a slightly darker shade.

When there was deep, still water, the river froze right over and then you heard the eerie scraping noise as all the ice floes invisibly passed underneath, dragged along by the current. But it would be quite a while before you could walk on the ice. The river in winter was alive, organic and took its time to freeze.

In the upper reaches of the Suru valley I had the distinct feeling of being in no man’s land, limbo, trapped between two very different worlds. A strange zone with few, if any, signs of habitation, as if passing from one country to another, from one language, belief system and philosophy to another more colourful, expansive world. This was like walking on thin air down a vast mountain corridor wracked with harsh, cold winds, low cloud and occasion snow flurries. Very occasionally peaks could be glimpsed. All unclimbed, apart from the twin summits of Nun Kun. All beckoning. Maybe the mountains talked to each other. Maybe the glaciers had a language of their own, crevasses their own code of practice. Humans were almost superfluous unless they meditated.

The more I walked, the more the mountain silence began to penetrate my bones and my way of thinking. If you looked carefully there were many different zones, all related to altitude, grazing and snowline. Near the villages were the zones of farmers, then the zones of shepherds and yak herders, and the more subtle Buddhist zones of monasteries, monks and nuns, where meditators spent weeks, even years, surveying the peaks and glaciers. It was this last zone that interested me most of all. Zangskar beckoned from afar.

As the path began to rise towards the yellowy light of dawn I caught sight of movement far below. Unusual … a figure, a man who crossed the river above a waterfall with a bundle of dried grass strapped to his back. Quite where he had come from I could not make out, or even where he was going, but he must have been out there all night.

And then he came up towards the road and I saw that our paths would cross. He was cheerful, despite being very cold, and had taken his rough homespun trousers off to cross the river. His legs were still bare and dripping; in his cummerbund, stowed away, a small sickle about six inches across. We greeted him warmly and I marvelled at his tenacity. I was put in mind of Matsuo Basho, the famous Japanese haiku poet, and his observations on Japanese peasants in his Narrow Road to the Deep North.18 I felt as if I were on my own narrow road, only I was going south and east not north. But our feelings about winter were the same. This unkempt but cheerful man was on a voyage all of his own. There were no villages up here and what he was doing was something of a mystery.

Only an old man clutching a sickle –

Drops of water – dried grass

Silvery beneath the crescent moon

His cloak covered in patches.

Feet and legs bare

Shades of things to come.

We passed like ships in the night. His greeting a handshake. His smile infectious. More than anything else this cheerful old man and his small parcel of fodder strapped to his back told me about the precariousness of their lives. Here every blade of dried grass counted. Maybe he was searching for an animal, like the famous ox-herding pictures used in Zen teachings, or returning from a trip over the other side of the mountains leading a yak or dzo for sale. You never knew how long winter was going to last. It was always a gamble.

Boundary of Buddhism

Sometimes where a stream crossed the road, it froze over into a great ice sheet maybe a hundred yards long. Each horse was gently coaxed across. We dug out frozen earth with a stick and scattered it on the ice so their hooves could get a grip. A broken leg up here would have been a disaster, for a horse could not survive the night. And if we lost one horse, the other three could not carry the extra load. Slowly I began to admire the horses’ tenacity. They were bred in Zangskar, so in a sense they were going home.

Usually we stopped around midday for an hour. With three pieces of dried yak dung you can make a good fire set between three stones. If it was dry it broke with a crack. There was often no firewood, just scrub. Dried dung from the summer’s grazing was essential. No fire – no warm food.

At one point we passed three small lakes that were so still they reflected the mountains perfectly. Half frozen over. Each line, like a ripple, led right round the pond, a night’s frost creeping out from the shore, an inch, then six inches, then a foot, then several feet at a time, until, like the previous night, it covered half the lake, the contours in the ice like tree rings recording the frost’s nocturnal advances. The following night it would freeze over completely. At one point I looked back at the Nun Kun peaks and saw a great rock face towering over the valley. Even from twenty miles it looked magnificent.

After the second day’s long march I saw the first prayer flags. The boundary of Buddhism, a psychological, social, linguistic and religious frontier. This was where Zangskar really began. From now on I was in Buddhist territory and despite the cold wind it felt very different. I felt like I was coming home and repeated the odd mantra under my breath. I sensed a degree of protection, as if the local gods were now on my side. Buddhists left nothing to chance.

Scores of prayer flags were strung out from long, thin willow poles anchored into small cairns. They are usually found on the summits of passes or at other key points on the journey such as river crossings. It is where the spirit of the pass or the mountain or the village resides. A place of offering and worship.

These flags were faded and fluttered in the cold, dry wind, each colour symbolising a particular Buddhist idea or element. Yellow is earth, green is water, red is fire, white is wind and blue is outer space. Five elements instead of four. On each cotton flag there were mantras and Buddhist prayers. A wind horse is often printed in the centre, special horses (lungta) that carry the prayers galloping on the wind. In each corner there are mythological creatures: a Garuda bird – wisdom; the dragon – gentle power; the Tibetan snow lion – fearlessness and joy; the tiger – confidence. This was a complex spiritual world, a potent mixture of Tibetan Buddhism and shamanic, pre-Buddhist folk beliefs still very important in the mountains, particularly when the elements are unpredictable. Compassion and inner strength transmitted on the wind.

These prayer flags are often hand printed from old wood blocks that have seen many seasons. Flags are replaced at certain times of year by local villagers and they have a distinct psychological effect, as if harnessing the powers of nature. A powerful political and territorial statement, for although the path gets tougher and the altitude higher, at least you know that you are on Buddhist soil at long last.

You have entered the land of Buddha’s teaching, where following the path to enlightenment is the aspiration of many. Indeed, the word for Buddhists is simply nangpa – the ‘insiders’. It means they are inside the teaching, and that they are seeking the solutions to existence and philosophy and life’s perplexing questions within the very nature of mind itself, a radical quest based on long experience of silence and inner common sense.

Nangpa is not to be confused with nan pa, which means bar-headed goose, the species that flies over the main Himalayan range twice a year on migration. They breed in Ladakh and the lakes of Tibet, then fly over the Himalaya to winter on the wetland areas of north India, reversing the journey in spring. They have been seen flying close to very high mountains – even over Everest – and are very strong flyers indeed. One Tibetan source says, ‘You cannot see the summit from nearby, but you can see the summit from nine directions and a bird that flies as high as the summit goes blind.’19 Maybe the geese are temporarily snowblind.

Geese are mentioned many times in Buddhist teachings to symbolise the mind’s migration and the wisdom of non-attachment, as well as being a metaphor for enlightenment, which is ‘like a goose arriving at a great lake’.

Mantra

Having passed the first prayer flags we camped for the second night beside the track, sleeping out rough as always. We had collected twigs and dried yak dung as we walked. To make lighting a fire easier, small pieces of dried horse dung were soaked in kerosene and then ignited. You knelt down and blew till the fire took. Another trick was not to camp anywhere near a village. All the firewood and scrub would have been collected and there would be little or no grazing at this time of year. The villagers needed every scrap of fuel they could find.

That second night we slept out in what must have been a summer grazing camp with low walls. Darkness came quickly to our shivering fingers. Lighting stoves and using matches became a major preoccupation. Tying bootlaces and doing up buttons became a chore. The stubbornness of numb fingers lingered in your mind, for without your fingers you can do nothing. Not even strike a match.

The stillness was remarkable. Only the odd noise of horses moving from foot to foot as they slept standing upright in among the rocks. Our breath froze. No one else was on the move in the mountains at this time of year. The snow was already a month late, so we were cutting it very fine indeed. The frosts were unbelievably hard.

Boiling point is always lower at high altitude – pressure cookers are useful when cooking rice, so long as they don’t explode – and mountaineers use the boiling-point temperature as a guide to height. There were graphs that could be used to measure the altitude. Roughly speaking, at 13,000ft the boiling temperature would be about 87°C, which made tea less appetising and porridge a little gloopy, and you lost 1°C for every thousand feet you climbed. So at 20,000ft your tea would boil at roughly 80°C. A good rule of thumb. I had my own altimeter in a leather case and wore it round my neck. I consulted it every day. It was my compass, my lucky charm, my amulet.

On the third day I saw the first Buddhist monastery, perched on its lone rock far away in the distance. Here was something to aim for, a navigational aid, but in the end we took a short cut to one side. The main building was whitewashed but the Temple of the Guardian Deities (the Gonkhang) at the rear was red, which made a great contrast. This was Rangdom Gompa, a Gelugpa monastery, yellow-hat followers of Tsongkhapa, the great 14th-century sage.20

The valley opened out into a vast flood plain, barren in winter but with a great sense of freedom. Five valleys meant five winds and five rivers. The monastery stood alone on its great rock, a wonderful spectacle but also cold, desolate and dusty. There were two villages: Zhuldok, the nearer one, and Tashi Tanze, tucked away on the other side of the monastery.

In November you walk on borrowed time. In Zhuldok I counted about twenty houses, roofs all heavily laden with neatly stacked fodder and firewood, ready for a long winter. The houses were not crammed together but separate, about thirty yards apart. Windows were larger than those down in Suru. More wood, more glass, more windows, more prosperous, their main wealth coming from selling horses, cattle and yaks in the autumn.

There were also fewer people. Monkish celibacy and fraternal polyandry saw to that, although I was never quite sure how the women felt about it with two or even three husbands. But in the Buddhist world women can only inherit land if there are no brothers. They are then in a very strong position, and can even hire and fire husbands if they want. It often depended on the size of their landholding and how many workers they needed. Arrangements seemed to be very flexible. Some men had two wives. Some women had two husbands. Divorce was not uncommon. Then there were nuns. As a culture they had learnt to keep the population down. The land can only support so many, and in winter food becomes scarce. Who can predict how long a winter will last? Instinct, intuition and ancient customs have a way of keeping you on the straight and narrow.

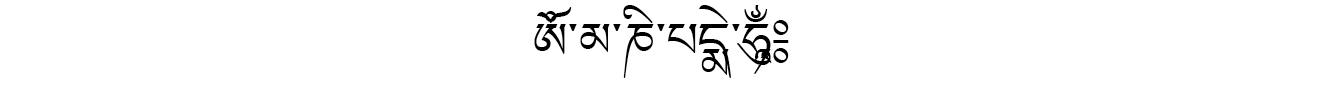

Om mani padme hum

In Zhuldok each house was daubed with the mantra Om mani padme hum, six syllables invoking wisdom and the inner path.21 They also had a line of red dots along the wall at waist height to keep the ghosts and evil spirits away, and the odd red triangle daubed on the corners of the house – Buddhism and Central Asian shamanism in one convenient package. Even wooden windows were outlined in ochre and black to give them a greater presence. The windows were the eyes of the house.

Heady stuff early in the morning. Om mani padme hum. Not a bad mantra to be walking to, repeated softly under one’s breath, each step a syllable.

Wind horse

Outside one house a woman leaned out wearing a perag, her headdress covered in rough-cut turquoise. She offered me a jug of yogurt that she had just made, saying, ‘Dun, dun, dun’ (‘Drink, drink, drink’). It was the old rule of travelling, a curious friendship that exists between those who are on a journey and those they pass. And yet I was a stranger in winter. I accepted the yogurt willingly. Such generosity.

The yogurt had a smoky flavour a bit like peat smoke, which gave it a fine edge. It was sharp. How they keep their yogurt cultures alive in the winter was remarkable. Yaks stood around the village loitering and were then driven off to some last patch of grazing by a young girl with a long willow wand.

All over Ladakh and Tibet the mantra Om mani padme hum is repeated thousands and thousands of times every day in monasteries, on prayer wheels, in private contemplation, fluttering on the prayer flags in the carved stones and in the murmured repetitions that accompany every walk of life. Then there are the 100,000 prostrations that can take several months to complete. In Phuktal Gompa I once saw an old but very fit man doing his prostrations on a wooden board. He had small white pebbles that he moved every time he completed ten, then a hundred, then a thousand. I think he did a thousand prostrations a day, so it would have taken him a hundred days. Sometimes pilgrims prostrated themselves full length along a road or path, mile upon mile. Humility itself.