Полная версия:

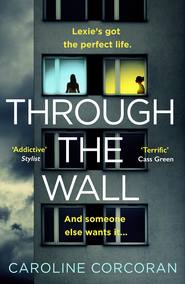

Through the Wall

I know about Harriet’s love for karaoke as her friends laugh and groan that they have work tomorrow. But then the intro kicks in and they stay and there is whooping. More friends join them. The joy multiplies. And there is always so much noise.

Now, the piano. I put pillows over both of my ears, but her sounds – always there, competing against our quiet home – are impossible to drown out.

Harriet writes songs for musicals that thousands of people hum on the bus home from the West End. She’s interviewed regularly for industry websites, sounding intimidating-smart. She is successful and rich, I presume, if she lives here. In this building, Tom and I are the exceptions with our normal salaries, and we can only be here because Tom’s parents own our flat and they’ve let us rent it for way below market value.

I realise I’m googling her again. I look at the picture of Harriet on her professional website. She is tall, striking and handsome and she looks powerful. I like her mouth. I envy her smooth, silky blonde hair. At school, she was undoubtedly the popular girl; a person who wouldn’t have sought me out as a friend as I battled my fringe of frizz and Play-Doh thighs.

In her flat, which doubles as a studio, Harriet writes and rewrites lines, her bare foot on the pedal of her piano; painted, unchipped fingernails flicking up and down before she scribbles down what she’s created. Harriet is a creator, she creates, she is creative. Purposeful, she is often so lost in her work that she forgets her plans and is late as she dashes to meet friends for brunch. She picks up flowers at Columbia Road, to sit on top of her piano and make a bright home even more colourful. She knows her own mind and tastes, never decorating her flat with something generic from a chain store, and to men, she is the whole package: smart, buckets brimming full of fun and utterly gorgeous.

Oh, I’ve never met her, of course.

I saw her once getting out of the lift when I had taken the stairs during a low-level fitness drive. I’ve found her mail in our postbox and shoved it into hers, and sometimes, like now, I Google her name. And yet I feel, somehow, like I know her.

From my home-office, aka the sofa next to the wall, I see my next-door neighbour, Harriet’s, existence happening, and it is plump and full and bursting.

Meanwhile, I have been here for three hours now with the start of back pain, flapjack on my chin and only seven sentences of my 2,000-word copywriting project on the page.

I wipe crumbs from my lap. I am no Harriet.

Just getting on the tube, says Tom’s text, later. Curry?

As I reply, I notice the stain on my – his – pyjamas and mean to change, but then I get distracted looking at the Thai menu.

Curry is bad. Curry means my size 12 jeans will dig into my skin. Curry means that we are unlikely to have sex tonight, when we should be doing it any chance we get.

Our impromptu and erotic sofa sex didn’t reap rewards and now almost a month has passed.

My ovulation sticks don’t say we’re in the window yet, but Great Doctor Google, alongside freaking me out about everything I do, have ever done and will ever do in my life, suggested that the more, the better is currently on-trend in medical policy. The idea that there is an ‘on-trend’ in medical policy is a worry if I think about it, so I don’t and instead choose my side dishes. I add duck spring rolls to a list of things I worry are stopping me from getting pregnant. They have many, many companions on that list.

In reality, we have no idea yet why I’m not pregnant. We have no idea why I got pregnant once, miscarried, and why it never happened again. And why, two years later, we are still static, waiting to move on and realising that we were so sure that I would get pregnant again, we never even properly grieved.

With every month that passes, anxiety wraps itself around me more tightly as I convince myself that it’s my fault. Despite trying everything. Despite following Tom, who works away sometimes making TV documentaries, around the country to have sex at the right time. Despite once buying a sexy nightie from Figleaves lingerie and staying in a Travelodge in Hull for a whole bloody week.

But beating myself up is something that’s been happening more lately, increasing alongside calories and sleeping as I do other things less: see friends, pluck my eyebrows, wear clothing items without an elasticated waistband. Laugh.

Through the wall, to snap me out of my internal chatter, comes Harriet. She slams her piano in frustration and then I hear a phone ring.

‘Yeah?’ she says, brusque, like people who are busy do. I am not even busy in this, the week before Christmas, the busiest week there is.

It must be a delivery driver, because ten seconds later I hear her buzz someone up and answer the door, shrieking about the beauty of the flowers. An early Christmas present? From a boyfriend? A friend? Her mum?

I peel myself away from the wall and nestle into the sofa. I’m home so much now that I work for myself that Harriet constitutes a concerning amount of my human interaction.

I picture her in heels, phone snuggling into her palm, hopping into her taxi, running out to dinner, to lates at a gallery, to taste potent festive cocktails. And I’m reminded of the old me, the me before fertility worries happened and sprawled over my life.

I shuffle to our bedroom in my worn-out slipper boots and rummage around in the wardrobe until I find the box I’m looking for. It is, as they always are, an old shoe box, full of photos that were supposed to be filed away in albums that were never bought and now live sandwiched between thank-you cards and badges from hen dos and birthday invites and leaving cards filled with in-jokes and old ticket stubs.

Somewhere along the line I stopped being this person who inspired people to turn cards around and write up the sides, who brought on exclamation marks and capital letters and leading parentheses.

I picture myself in my old job at a women’s magazine, where I had a reputation for always coming up with the best interview ideas.

‘Lexie will nail it,’ people would say, and I had the confidence to agree. I shared in-jokes, suggested new places for lunch. And then I shrunk. Now, as people sing Christmas songs outside my window and eat their fifth turkey roast of the month, I am alone, again, waiting.

I don’t know how life became this limited little space. I don’t know when I crammed myself into a box that was only just big enough for me, because I used to be a Harriet, too. And I am envious.

5

Harriet

December

I’m halfway to a work Christmas meal – the kind where I preordered my soup, turkey, tiramisu in October – when I realise that I’ve forgotten my phone and have to head back to the flat.

I nearly trip when I get off the bus, swear under my breath.

I’m too clumsy and tall for these heels, and I make a note to switch them for sneakers when I get home, despite the fact that I will never rock a trainer in the breezy way I’ve seen other girls do – in the way Iris does – that bares a chic, non-icy ankle. How are the ankles of all of these people not freezing?

On me, a sneaker–jeans combo will look as though it belongs on an awkward thirteen-year-old on a school trip, not a thirty-something who should have mastered her classic look by now. I look down at myself: far from it.

I swipe my fob against the screen and pull the door to just as someone is getting in the elevator. I curse my timing, because there is an unwritten code in this building that no one shares elevators, when I notice the man who has beaten me to it.

His hair is dark, curly, wildly untamed. He shoves it impatiently out of his eyes with each hand, alternately.

And I breathe like I am due to jump out of a plane in two seconds because an alarm bell has gone off and is drowning out everything else.

It’s not just this man’s hair. It’s his dark eyes, it’s the hunching of his shoulders as he heaves his large rucksack onto his back and puts a takeout food bag on the floor. It’s the sigh he does, so internal for an external noise. It’s his long legs and his straight jeans and it’s his nose, slightly too Roman for most but not for me.

This man and my ex-fiancé, Luke, who used to live here in this flat and get in this elevator with me, do not share a passing resemblance. Instead, they are doubles. Identical. Interchangeable.

For once, I climb the stairs and slam the door of my flat behind me. But like the Thai spices, the man from the elevator has crept in anyway. I know – rationally, I know – that it wasn’t Luke, that it couldn’t be Luke, that my ex-fiancé isn’t here, in London, clutching his takeout in the elevator of my building. That after what happened, his former home is the last place he would ever come. But there is a part of my brain that the message hasn’t reached and that’s the part that is making my heart hammer into my chest, surely audible through the wall to next door, I think, as I realise I am leaning against it. I gasp for air.

After a few seconds I hear Lexie, her tiny voice quiet, gentle, the opposite of my own. A northern lilt, I sometimes think, though English accents are still not my forte.

‘Tom?’ she asks, raising her voice to carry into the kitchen. ‘Can you bring me a …’

But the end of the sentence falls away. As ever, there’s just enough wall between us to mask life’s detail.

But Tom. Not Luke, Tom. Tom from next door. I must remember that, when my heart starts racing, when my mind starts racing and at 4 a.m. Especially at 4 a.m. I pour a glass of wine, down it and – forgetting to switch my shoes – kick the generic flowers that were delivered from a generic former colleague to say a generic thank you out of the way and head out with my phone, trying to fight a feeling that Lexie from next door has stolen my Luke. That Lexie from next door has stolen my fucking life.

6

Lexie

December

‘I miss Islington,’ sighs Anais as I flick the kettle on and she yanks off a tan Chelsea boot in the hall behind me. ‘Bloody Clapton.’

I’ve known she was coming round for a week now – she had a Christmas lunch around the corner – but still I had run around flustered for five minutes before she arrived. Endeavouring to put on eyeliner, remember how real people (I haven’t really considered myself to be one of those since I started working from home) dress and shove piles of post into drawers. Tom’s been away for a week now. I am flailing.

‘Remember why you live in Clapton, though,’ I say, brandishing a mint tea box and something ridiculously expensive from Planet Organic at her, and she nods to the latter, of course, because we are middle-class Londoners. ‘You own your place. No chucking your money away on rent.’ I sigh. ‘We’ll be here forever, because Tom’s dad will never put up the rent and we’ll never get anything better so we’ll never have the motivation to get a mortgage.’

It’s not just Anais; I say this to everyone, all the time. It’s my only response to my self-consciousness over how lucky we are to have moved this year into a Central London flat that has its very own swimming pool in the basement.

It’s still such a surprise to me, too; my own parents have barely lent me twenty pounds in my life – they’re of the ‘learn the value of money’ school of parenting. I’ve been encouraged to be utterly independent. Which makes this whole scenario pretty ironic.

Now, for less rent than my friends pay in Zone Six hellholes, I live somewhere where there is no paint chipped in the communal areas but walls that are freshly covered in high-end magnolia once a year. Where cleaners spirit away dead flies or discarded ticket stubs with the speed of a five-star hotel and then fling the windows open so that the feeling is hospital sterility. Where every type of night and day life we could need is in walking distance.

Right now, Islington’s anonymity soothes me. I walk out of my flat with nowhere marked out as my final destination and I wander up the high street past hipster thirty-somethings with children dressed in fifty-pound jumpers on scooters. At weekends, I clamber onto the bookshop on the barge on the canal, picking out piles of worn, second-hand classics. I smell the brunch that’s being eaten in seven-degree cold on the pavement like we are in Madrid in July and I know that that wouldn’t happen anywhere else in this country, but does here, because we are in a bubble. Nothing is real. Nothing gets inside.

Round here, CEOs play tennis at Highbury Fields with their friends like they are fifteen. In summer, I watch thirty-somethings charging around a rounders circle with friends. At the pub, there will be no locals but there will always be someone who is twenty-two and excited, who has just discovered that they can get drunk on a Monday and eat an assortment of crisps for dinner without anyone telling them otherwise.

On sunny evenings, we drink gin and tonics in overpopulated beer gardens that spill onto pavements. For Christmas, I have bought everything I need within the radius of a ten-minute walk from my flat. We are spoilt children and I adore it. It’s not a feeling I’ve ever known before.

But by repeating my mortgage conversation on loop, it’s become true to me. I’ve started to care about ownership and getting my hands on an enormous loan that will never be paid off. Whatever I had, it turns out, I would look over my shoulder to see what someone else had and want it, too. This is me. Perhaps it is everyone.

And there are downsides to life in this part of London.

We’re transient because we know this isn’t where we will settle.

It does happen: I look up at the family houses that surround Highbury Fields and like everyone, I wonder who could possibly have that life, that real life, living here beyond their thirties and becoming a family here, becoming old. But there are bins outside, spilling out with pizza boxes and wine bottles and toilet roll holders and nappies. It’s real.

Most of us, though, will never be the 0.000001 per cent with their pizza boxes. If you’re thirty-nine, Islington looks at you sadly like you’ve stayed at the party a little too long. Perhaps you could have a quick Sunday afternoon picnic on the green on your way out but then yes, it will be time for you to head off to the suburbs.

Anais is doing just that and building a life. Where she goes to sleep, there are old food markets and boozers and there are people who have lived there forever, who sell vegetables loudly and look at you blankly when you talk about brunch. There are new people, sure, but it’s not like here. Here, heritage ebbs away every time a greengrocer’s becomes a gin bar and a rental notice goes up in the window of the old pub. We are all to blame: I spend Sundays strolling in between market stalls selling lockets and trinkets and soaking up the feeling of it all, and then I spend my money in Waitrose. I am part of the problem. I am at its heart.

‘Mortgages are overrated and I have no idea why everyone is so obsessed with them,’ Anais says as she rummages in her bag for the box of brownies she’s brought with her. ‘Very much like babies.’

I bristle. She puts the brownies on the side.

‘Salted caramel,’ I say, reading the label and trying to distract myself from the irritation that’s surging through me over her flippancy. ‘Thanks.’

Since we were at university together, Anais has been vehemently opposed to procreating and didn’t change her mind even when she met Rafael. He’s Spanish; she’s Barbadian. If you were the kind of person who wheeled out terrible clichés, you’d tell them they’d make beautiful babies.

I’m not and I don’t. If struggling to conceive has any upsides, it’s taught me emotional intelligence. I make promises to myself that whatever happens, I will never be one of those people who don’t consider for one second that by proffering their opinions on your position on having children, they might have just ruined your whole week. You don’t know. You never know.

Anais and I did our journalism postgraduate course together and while the rest of us only manage yearly get-togethers, Anais and I are still proper friends. Her: a political editor for a broadsheet. Me: a copywriter for various dull brands who pay me to produce words about their products. I’m currently writing instructions for a washing machine. This isn’t how I saw it going when I turned up ten years ago for my first day at university, clutching a copy of Empire magazine and declaring my intentions of becoming a film critic.

But I left my last job at a magazine because I returned home four nights out of five stressed and panicked about something that had happened to do with internal politics. The sort that at the time seem like the centre of the universe and really are part of some distant solar system that no one should care about, ever.

And, mostly, because Tom and I had been trying for a baby for two years and, since the miscarriage, nothing else had happened. I wanted to alter something. I wanted to relax, get some work-life balance and go to Pilates at 2 p.m. if I fancied it. The problem was that I rarely fancied it. The problem was that being at home alone all day without the distraction of those internal politics and a 10 a.m. meeting to prep for left me depressed and so anxious that a two-minute walk to the post office felt far beyond me. I zoned in obsessively on the absence of a baby. As time went on I grieved more, not less, for that baby who didn’t make it. I’m not saying that leaving my job was the wrong decision. But it certainly hasn’t been a quick fix.

‘It’s been such a ridiculous run-up to Christmas at our place,’ Anais says, taking her tea from me as she frames herself, beautiful, in the entrance to the kitchen. ‘I’m still so jealous of you working for yourself.’

And I look down at my one Official Seeing People outfit, pulled on two minutes before she arrived and to be discarded one minute after she leaves, and glance at her phone on the side, lighting up with messages and urgency, and I think sure, Anais, sure.

‘Working from home, all that flexibility.’

Then she comes up with a very specific example of this.

‘You can bake a potato while you work.’

That’s it. That’s what I was after when I held that copy of Empire. Baked potatoes. While I work.

‘You can go for a run at 3 p.m.’

Because I do. Often.

She pads in her tights through to the living room.

‘Jesus, what the hell is that noise?’ she says as she sips her tea. Something with fennel.

I head back to the kitchen.

‘Oh, just Harriet!’ I yell as I press my own teabag against the side of the mug and fish it out. I decant the brownies onto a plate then I follow her in and laugh, because she is stood, ear pressed to the wall, to listen to Harriet’s latest composition involving chickens and a farm.

‘Get away from there,’ I stage-whisper, even though we both know she probably can’t hear us over that level of farmyard-based noise. There is a chicken impression, in rhythmic form. We are folded, creased, with laughter.

When we calm down, Anais sits, doing a noiseless impression of someone earnestly singing an opera as she curls her feet under her on the sofa.

She leans and takes a brownie from the plate that is sat on our tiny coffee table.

‘Does she do that all the time?’ she asks.

I think about it.

Suddenly it seems weird that I have started to think this is so normal, this woman singing loudly about love, dreams, emotions and chickens. I hear her pound the piano in frustration. I hear her ARRRGGGHH out loud when something doesn’t go well. And I live alongside it, like her cellmate.

‘Yeah, pretty much. There you go, another downside of our Islington life. Successful music writers move in next door and sing weird songs about farmyard animals.’

We laugh, a lot, but then there is a lull.

‘So, how are you?’ I ask.

As I eat my brownie, she tells me about the new app Rafael just designed, a Korean place they’d tried at the weekend and the trip to Mexico they’ve just booked. And then, when I can’t stop her any longer with my questions, questions, questions, she asks me the dreaded one from her side: ‘How about you – any news?’

I mime a full mouth and take a second.

It’s loaded, that question, once you get into your thirties. It means ‘Are you getting married, having a baby, buying a house? Do you have an awesome, game-changing new job that pays you so much money you can buy in Notting Hill?’ And if you don’t, if none of those things exist, you feel like you have failed at news. Sometimes I think I want a baby partly so I can succeed at news.

‘Not really,’ I say before spinning some mundane work and a trip to the theatre with Tom’s parents into news.

Because you can’t actually have no news. We must be busy and rammed and manic and constantly doing, and no news isn’t allowed. I dust brownie crumbs off my chin and onto a plate.

After Anais leaves I change back into my – Tom’s - pyjamas and consider why I didn’t speak to her about The Baby Thing.

Every time we’ve done this and I’ve omitted it, I’ve surprised myself. Because that is my news. That’s my story. Anais is my friend and I am a sharer. And not mentioning it means I have a low level of nausea about the unknown elephant in the room every time we meet. I didn’t even tell her about my miscarriage. Anais, my best friend, doesn’t know that I was pregnant. Doesn’t know about the biggest thing that ever happened to me. That seems crazy now but at the time I had hoped it would be a footnote to some good news, to the best news.

Not telling Anais what is going on in my head also means that we are drifting. I know it and she knows it; I can feel the chasm getting wider but I can’t do what I need to do to close it. So why?

I come to this conclusion: once it’s out there, there’s no taking it back. Once you say you’re trying, that’s your thing. That’s the ‘news’ they mean. That’s the black cloud over my head that everyone will see.

‘Are you okay?’ Anais asked into my ear as she left, hugging me close. ‘You seem …’

But I avoided her eyes, shrugging out of our cuddle and seeing her out with some paint-by-numbers thirty-something rambling about a busy week and work worries.

I eat the rest of the brownies, alone, leaning over the kitchen sink. It’s a while before I hear from Anais again; definitely longer than normal.

7

Harriet

December

Suddenly, there is a loud giggle from next door that makes me jump. It’s not Lexie, it’s a woman who is less softly spoken, and I can hear Lexie replying, louder than normal to match her friend, and laughing heartily.

Tom has been away for a few days now, I think, so Lexie’s spending some time with the rest of the people in her life. I am irked at her greed. A beautiful boyfriend who brings her curry and loves her and friends, proper friends, who share in-jokes with her and pop round for tea. Does this really happen?

‘Just Harriet,’ she shouts as I stop playing my piano for a second and jolt.

It is the incongruity of my name, heard through the wall where I thought that I did not exist. But like they exist to me, I exist to them. I look down and see my hand shaking. The spell is broken and I can’t even focus on my piano.

Then they laugh again, loudly and together.

Through the wall, I am a person. They acknowledge me. They speak about me. They laugh at me. If there’s one thing I can’t take, Lexie, it’s people laughing at me.

My heart is pounding.

It’s been three days since I saw Tom/Luke getting into the lift with his curry. The hair. The shoulders. That nose. I shiver. I can’t sleep and I’m behind on a deadline for the score on a children’s musical. The guy I am working for is getting twitchy and my usual desire to impress has deserted me. I don’t care. I am focused on Lexie. I feel a surge of rage.