скачать книгу бесплатно

Through the Kurdish underground, he reached the American operations headquarters in the Kurdish town of Zakho. The Americans, wary at first, flew in four intelligence officers to debrief him. His wife, who had gone into hiding, was helped out by the same Kurdish underground, and their baby daughter was smuggled to Jordan by friends.

With the help of the Americans, he was granted political asylum in Vienna where many Iraqis live. But an import-export company he set up has failed to prosper and, because of Vienna’s close connections with Baghdad, the city has a high number of Iraqi government representatives. Any one of them, he fears, might be a potential assassin.

His anxiety heightened last September when he received a letter from the Iraqi embassy saying he had been granted an amnesty and should return to Baghdad. The message came on his personal fax machine, even though he is living in hiding and gives the number only to close personal friends.

Yahia is afraid to send his daughter, Tamara, now five, to school in case his whereabouts can be traced through her. He keeps his wife, daughter and Omar, their 18-month son, with him even at the office.

Most of all, he finds it difficult to recover any sense of himself. ‘Uday stole my life, my future, my identity,’ he said. His wife agrees. Watching videos of Yahia posing as Uday in Baghdad, she shivered when she saw the man on the screen roughly grab a tissue proffered by an aide.

‘He changed so much in his manners,’ she said. ‘Before, he was a normal person, but after he was tough and violent. He would hit me or kick me, and many times I thought of getting divorced. But I know now he is trying very hard to recover himself.’

Blood feud at the heart of darkness

8 September 1996

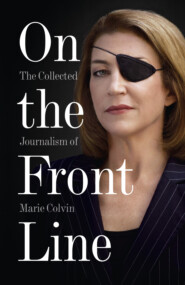

Terrible deaths in the family of Saddam Hussein illlustrate the brutality of a tyrant still powerful enough to shake the world. Marie Colvin reports from Oman.

In the glistening marble and gilt palace of Hashemiya, high on a hilltop overlooking the Jordanian capital, Ali Kamel, nine, spent many hours of his exile drawing brightly coloured pictures for his grandfather. Ali never learnt why he was living in this strange place. He was too young to be told his family had fled there in terror of the grandfather he loved: Saddam Hussein.

Hussein Kamel, Ali’s father, had been the Iraqi tyrant’s closest adviser. He had risen from lowly bodyguard to head of military procurement, and had been put in charge of rebuilding his country after the Gulf War. Kamel even married Saddam’s favourite daughter, Ragda. But he fell out with the dictator’s son, Uday, a thug who had repeatedly killed on impulse.

In August last year, Kamel was in such fear of his life that he took Ragda, Ali and his two daughters across the barren Iraqi desert to seek safety in Jordan. Other members of the family accompanied him in a fleet of black Mercedes.

There was a brother, Saddam Kamel, who had been responsible for the dictator’s personal security. His wife Rana, Saddam’s second daughter, came too, clutching their three children. A second brother followed, with a sister, her husband and their five children.

The family’s terrible fate, details of which are disclosed here for the first time, gives a chilling insight into the methods used by Saddam to retain power despite isolation from the world and hatred at home.

The defection of so many family members was a devastating blow to the tyrant. In the days that followed he retaliated: scores of Kamel’s relatives and followers disappeared. For months afterwards Saddam plotted his revenge with the cunning and lethal aggression that was so much in evidence again last week in his latest challenge to the international order.

Kamel’s family settled comfortably at first into the luxury of the palace provided for them by King Hussein of Jordan. Stuffed with Persian carpets and other finery, it provided them with a secure home behind the shelter of tall, white stone walls.

Ali took lessons from a private tutor. Although the boy did not excel in his academic work, it did not take him long to work out that all was not well with his parents. Kamel had expected to be seen by the world as the potential successor to Saddam. But he had too much blood on his own hands. The Americans came only to pump him for information about the Iraqi military establishment. Even the Iraqi opposition shunned him.

Early in February, Ali often saw his father walking in the palace garden despite the cold and rain, speaking on his cellular telephone. Hussein Kamel had become so disillusioned with exile that he had begun discreet negotiations to return to Baghdad.

It was part of Saddam’s game plan that he responded by making strenuous demands. Not only would Kamel be obliged to return millions of dollars he had hidden in a German bank; he would also have to provide a detailed written account of everything he had told his western interrogators, a lengthy process for a man who was barely literate.

His departure was precipitated by the growing impatience of his hosts with public statements in which he criticised the king. On the first day of the Muslim feast of Eid, he was visited by Prince Talal of Jordan, who told him he was ‘free to go’, the unspoken message being that he had outstayed his welcome.

Kamel strapped a pistol to his hip, drove to the home of the Iraqi ambassador and sat in animated discussion with him in the reception hall. Then they went to the embassy and telephoned Baghdad.

Once he was sure that Kamel had fulfilled the conditions set for his return, Saddam sent a video of himself, in which he promised he had forgiven his son-in-law. ‘Come during the feast,’ he said. ‘The family will be together.’ He implored him to bring all his relatives back with him. A written amnesty followed from the Iraqi leadership council.

Kamel made his decision abruptly. ‘We are going home,’ he announced to a family gathering. Ragda and Rana, suddenly frightened, began crying. At the last moment, Ragda telephoned her mother, seeking reassurance. But the phone was answered by Uday, who, in his latest outrage, had shot an uncle in the leg in an argument over an Italian car that he wanted to add to his collection of classics.

Ragda begged her brother to tell her the truth: would they be safe if they came home? ‘Habibti [Arabic for my love], I give you my word,’ he said.

Hours before he left, Kamel telephoned one of his few friends to say goodbye. The man, a fellow Iraqi, was appalled. ‘You know you are going to your death,’ he said. Kamel bragged that he had obtained personal assurances from Saddam. ‘To this day, I don’t know why he trusted Saddam,’ the friend said last week. ‘He was one of them. He should have known.’

Arriving at the border, the returning defectors were greeted by a smiling Uday in sunglasses and suit. The men were separated from their wives and children. Kamel would never see Ragda and Ali again.

With his brothers, he was taken to one of Saddam’s presidential palaces, where they were rigorously questioned about their experiences in Jordan and their contacts with western representatives and opponents of the Iraqi regime. After three days, they were released and went to the home of Taher Abdel Kadr, a cousin. Here, they were joined by two sisters and the women’s children. But their relief and jubilation were short-lived. Within 48 hours, they learnt from a statement broadcast on television that their wives had denounced them as traitors and had been granted divorces.

As dawn filtered through the windows of their villa on 20 February, a cousin who still worked at the presidential palace woke them with the news that they had been betrayed. He brought weapons. Grimly, the Kamels prepared for their assassins as the children slept on.

Their killing was a family affair. While army vehicles and police cars blocked off the neighbourhood, an armed gang led by Uday and Qusay Hussein, Saddam’s second son, surrounded the house. Uday and Qusay were accompanied inside by the former husband of one of Kamel’s sisters. He showed his loyalty to Saddam by opening the firing on his family’s house.

The attack, carried out with assault weapons, was ferocious. Although Kamel’s men fired back, they were swiftly overwhelmed. Some of the family were killed in the initial onslaught; others when the armed men entered the house. They included Kamel’s elderly father, all the women and at least five young children, gunned down in their nightclothes.

Outside in a parked Mercedes sat Ali Hassan Al-Majeed, a cousin of Saddam’s who had earned the nickname ‘The Hammer of the Kurds’ after gassing villages in northern Iraq with chemical weapons in 1989. Al-Majeed was on a mobile phone, describing each step of the assault to Saddam as it happened.

‘We have 17 bodies,’ he said. The only member of the family who was missing was Kamel himself. Saddam barked: ‘I want his body.’

As bulldozers were brought in to destroy the house, Kamel, naked to the waist, wounded and bleeding, burst from a hiding place inside and appeared at a door brandishing his personal pistol and a machinegun.

He had barely fired a shot before he was riddled with bullets. When the gunfire ceased, Al-Majeed walked up to the body and emptied his pistol into it. He dragged Kamel by one foot through the sand, yelling to his men and to neighbours cowering behind closed doors: ‘Come and see the fate of a traitor.’ The bulldozers moved in and the house was razed.

The massacre was a vivid reminder to the people of the ruthlessness of the regime under which they live. If Saddam was willing to eliminate close and even innocent members of his own family in such a fashion, there was no limit to what he could do to them.

During the summer, however, came two further reminders of the apparent futility of resistance. In June a member of the presidential bodyguard fired shots at Saddam and was executed. Less than a month later, according to western diplomats and Iraqi exiles, a rebel group of Iraqi officers planned to kill Saddam by bombing a presidential palace from a plane that was to have taken off from Rasheed airport in Baghdad.

The conspiracy was discovered and hundreds of members of Saddam’s armed forces were arrested. Between 1 and 3 August, 120 of the officers were executed.

Iraqis have grown used to atrocities since Saddam came to prominence. His first known political act was an attempt in 1959 to gun down Abdel-Karim Qassem, then the Iraqi leader. When he became president 20 years later, he began by accusing 21 senior members of the leadership of treason. He formed a firing squad with his remaining colleagues, and together they shot all the condemned men.

In the years that followed, his people learned to voice their opposition only to close friends and family. Criticism of Saddam is punishable by death, and the security services are ubiquitous. Iraqi couples do not even speak in front of their own children for fear they might innocently repeat something and bring down the wrath of the regime.

The long series of confrontations into which Saddam has led Iraq has made life immensely difficult in a country whose citizens should be as pampered as those of Saudi Arabia. Iraq, unlike most Arab states, has both oil and water. Two huge rivers, the Tigris and Euphrates, nourish the land, and before the imposition of United Nations sanctions following the invasion of Kuwait in August 1990, Iraq earned $10 billion a year by lifting 3m barrels of oil a day.

Much of the money was spent on creating not comfort, but the largest army in the Middle East. Within a year of taking power, Saddam ordered the invasion of Iran, starting a bitter war that lasted for eight years and left 1 million people dead.

The attack on Kuwait was another miscalculation. The 43 days of allied bombing, supported by Arab countries afraid of his might, destroyed not only military sites but roads, bridges, oil refineries, communications, sewage facilities and the rest of an extensive infrastructure built by oil revenues.

Last week’s conflict, in which Iraqi support for one group of Kurds against another provoked two waves of bombardment with American cruise missiles, was by no means the first test of the allies’ resolve since the Gulf War. But after previous confrontations, Saddam has simply waited out his enemies. Those close to him say he is proud to have outlasted in office both George Bush and Margaret Thatcher, who led the coalition against him in 1990.

The few who have risen in revolt have been crushed, but his inner circle has tightened around him and now consists almost solely of relatives from Tikrit, his home town.

According to Arab dignitaries who have visited Saddam, he has become so paranoid about his security since the Gulf War that he maintains 250 safe homes. The staff in each house prepares dinner every night as if he is to arrive; nobody knows where he will sleep until he shows up at the door.

The Kamel clan was not the first to betray him. Last June he was shaken by a coup attempt led by the powerful Dulaimi clan from his Sunni heartland that had been a pillar of his armed forces. Provoked by the torture and death of a clan member accused of involvement in a previous coup attempt, General Turki al-Dulaimi led his troops in a bold but suicidal march on Baghdad. The rebels were defeated in a day.

It has not escaped the attention of most Iraqis that while the latest confrontation has occurred less than six years after the Gulf War, the reaction around the world this time has been quite different. America’s use of missiles was backed wholeheartedly only by Britain, Canada and Germany. Although he lost a few isolated radar and anti-aircraft batteries, Saddam succeeded in dividing the coalition that had been ranged against him.

The main reason for the change was the nature of Saddam’s offensive. He did not roll his army across an international border and occupy another country, but sent a limited force of tanks and infantry into Arbil, a Kurdish city 12 miles inside the Kurdish ‘safe haven’ patrolled by allied jets.

He was also invited in by the Kurdish faction that represents the majority of Kurds, the Kurdish Democratic party (KDP). Other Middle Eastern countries saw the American intervention as a blatantly inconsistent piece of interference in an internal problem. The United States had not objected when Turkey sent 35,000 troops into northern Iraq last year to attack bases of rebellious Kurds; nor when Iran sent 3,000 troops across the border into northern Iraq last month.

Turkey and Saudi Arabia, among the countries that are the closest allies in the Middle East, refused Washington permission to launch strikes from their soil. The Arab League, for once in agreement, denounced the attacks on Iraq.

Just as striking, the first criticism of the American bombing came from a Gulf newspaper, condemning the action and saying that all Arabs should oppose it ‘as a matter of honour’. It was the first time since the Gulf War that any paper in the region used the word ‘brothers’ to refer to Iraqis.

France was critical and Britain was unable to get a resolution denouncing the Iraqi incursion through the UN security council following strong opposition from Russia. By the end of the week, Saddam’s tanks were still dug in in northern Iraq and the allied coalition was in tatters.

For now, Saddam may have little choice but to accept the establishment of a security zone inside its territory by Turkey, which says this is needed to fight Kurds battling for independence from Ankara. He should not be expected to be quiescent forever, however. He has every prospect of increasing his power and has a lot of grudges to settle. Those who know Saddam say the one certainty is that he never forgets and never forgives.

For the ordinary Iraqi, life seems likely to get harder. While the so-called ‘war rich’ who have profited from the black market in Baghdad continue to work on new palaces, most people are worried about food prices driven to new peaks by the crisis.

Privations, large and small, continued last week. People had to shower at 4am because electricity cuts meant there was no water during daytime. In a hospital in Baghdad, surgeons who no longer had paediatric surgical equipment operated on children with adult-sized instruments. ‘It is butchery,’ one doctor agonised.

Saddam’s offensive put into limbo a UN-negotiated deal that would have enabled him to sell oil for food. There now seems little hope of relief in the near future.

Life is more comfortable but barely less bleak for Saddam’s two daughters and their six young children. They were not in the villa where Kamel and his other relatives were killed, but face a dark future.

The two young widows were forced to move into the house of their mother’s sister, where they are virtual prisoners. They cannot go out. Their children were taken away and they have been told they may never see them again. Sources in Baghdad said Rana, who was close to her husband Saddam Kamel, tried to kill herself and had to be hospitalised.

Ali, his sisters and cousins are living a sequestered life in Tikrit, Saddam Hussein’s birthplace. Ali may still be drawing pictures for his grandfather in vain. He and the other children are being raised to know that their parents were traitors.

Middle East

The Hawk who downed a dove: assassination of Yitzhak Rabin

12 November 1995

Marie Colvin and Jon Swain

Her name was Nava, and she was everything that Yigal Amir, a rather serious student at the religious university of Bar Ilan, wanted. Amir, his friends say, was an arrogant man, lonely and aloof, who had never had a girlfriend before because no girl had been good enough.

He began pursuing her as soon as they met in the spring of 1994. ‘She was rich, pretty, clever, pure and religious. She had it all,’ said a fellow student. They dated for five months. ‘They never broke the limits of what is permissible between a religious pair, but there was a huge commitment.’ So intense was the relationship, they planned to marry.

Then, in January this year, she abruptly left him for his best friend, Shmuel Rosenblum. Amir was stunned. ‘The talk on campus was that her parents had disapproved of her marrying him because he was poor and of Yemeni extraction,’ the friend said. A month later Nava married her new boyfriend.

Amir changed. He had always been fiercely nationalist, with a deep religious belief that God’s holy land had to be zealously guarded by the Jews. He was utterly opposed to Yitzhak Rabin, the prime minister, and his policy of trading land for peace with the Palestinians.

Now he became outrageous, outspoken and dangerous. The extremist, angered and rejected, had tipped over into a potential assassin. ‘I think that not only political views caused the murder, but also his feeling of disappointment in his personal life,’ the friend said. ‘Suddenly we heard him talking about the duty to kill Rabin.’

A fellow student, Shmulik, recalled: ‘His arguments were always based on the Torah [the body of Jewish sacred writings and traditions].’ Amir would tell his friends that, since Rabin had given up parts of the land of Israel, it was a mitzvah (positive obligation) to kill him.

Eight days ago, on a Saturday night in Tel Aviv, he walked up to Rabin, pumped two exploding bullets into him, and discharged that obligation.

In the weeks before, Amir was on such a public rampage that it now seems astonishing that he was able to get near the prime minister with a gun in his hand and a clear line of fire. All last week, stunned Israelis asked why nobody had been watching him.

Amir had made no secret of his deadly intentions. He was a member of an extremist Jewish group that denounced Rabin for treason; he was dragged away by security guards for heckling Rabin at meetings; before he succeeded last Saturday, he had already made two unsuccessful assassination runs. Weren’t the groups of fundamentalist Jews who vowed to stop the peace process at all costs under any kind of surveillance?

The murder raised other, more profound questions. Nobody had believed a Jew would ever kill a Jew; despite the venomous rhetoric that had followed Rabin’s peace treaty with Yasser Arafat, the Palestinian leader, nobody believed that taboo would be broken. So what was this nation of Jews if the land had become more important than an individual’s life?

The shock and incomprehension deepened as Israelis learned more details about the killer in their midst. Amir grew up in the heart of Israel, the Tel Aviv suburbs, and served in an elite brigade of the army. His background might have given him something of a chip on his shoulder; he was a Sephardi, an Israeli descended from Jews who came from Arab lands, rather than an Ashkenazi, the elite of Israel who came from Europe and founded the state. But he had done well.

Born in 1970, the second of eight children, he was raised in a two-room house by his father, Shlomo, a scribe who supplemented his income with the ritual slaughter of chickens, and his mother, Geula, a large, warm woman who supported the family with a creche in the back garden. They had come to Israel in the 1950s from the Yemen.

Religion played a strong role in Amir’s life from the beginning, first at Wolfson, a school run by the ultra-orthodox Aguda movement and dominated by Ashkenazis. He was out of place as a dark-skinned Sephardi, but he surpassed everyone in his work.

When most of his fellow religious students opted out of armed service, allowed for those pursuing religious studies, he joined the elite Golani brigade while continuing to study the Torah at the fiercely nationalist Yeshiva Kerem De’Yavne institute.

In October 1993, a month after Rabin signed the agreement with Arafat in Washington to hand over land occupied by Israel in the 1967 war in return for peace, Amir entered Bar Ilan University. There, too, he was unable to forget his Sephardic background. Although he was a top student in the most difficult of Israeli studies – a triple course of law, computer and Torah studies – he always felt a misfit. When Nava left him, he felt it even more keenly: she was Ashkenazi.

As his politics became more virulent, he spent most of his time in the Institute of Advanced Torah Studies and in fierce religious and political debates. He began organising student demonstrations, obtained a gun licence and bought a short-barrelled Beretta 9mm, the gun he shot Rabin with. He wore it ostentatiously, tucked in his left trouser hip pocket, the handle protruding over his belt.

Somehow, though, he escaped the attention of Shin Bet, the Israeli version of MI5, even when he joined Eyal, a violently anti-Arab group operating in the West Bank and a venomous agitator against the Rabin government. He became a friend of its founder, Avishai Raviv, who was under surveillance and had been arrested. Still Amir went unnoticed.

In the final weeks he was a publicly angry young man who was hiding nothing. The incidents mounted. On 30 September, he went with other Bar Ilan students to Hebron, where about 20 Jewish families live at the heart of a city of 100,000 Arabs. There they went on a tour with a settler, Maisha Meishcan, a man who defiantly walks the streets with a cowboy hat on his head and an Uzi on his shoulder, and visited the site of a 1929 pogrom against Jews.

There, Meishcan revealed last week, Amir ‘beat up’ two Christian women pacifists, dragging them 20 yards, before police arrived. Two of the group were arrested but Amir slipped away.

A week later he was stopped and his identity details taken by police at a demonstration outside the home of a right-wing Israeli minister who had revealed his support for Rabin over the second phase of the peace agreement. There were other demonstrations. He was twice arrested and released.

On 23 October, Bar Ilan reopened. The last time fellow students remember seeing him was on 2 November, the Thursday before the assassination, at a computer class. He arranged with a friend for a lift to the university that Sunday. He never went.

On the evening of 4 November, at 5:45, Amir locked himself in his family’s garden shed and loaded his Beretta. This time his plan would work.

He had made his first attempt to murder the prime minister months earlier, in June, but at the last minute Rabin had failed to show up at a ceremony at Yad Vashem, the holocaust memorial in Jerusalem. Thwarted, he tried again in early September, when Rabin was opening a new road in Herzliya, near Amir’s home. He joined right-wing demonstrators against the premier, gun in pocket, and got close before security ‘closed like a clam’ around the prime minister.

Now Amir loaded his gun with special hollow-point bullets prepared by his brother, Haggai, 27. In the previous weeks, while Amir was demonstrating, Haggai had painstakingly drilled holes in the heads of about 20 bullets, filling the tiny space with mercury. Ordinary bullets pass cleanly through a target, but hollow-points flatten like a mushroom on impact, bounding around in the body and ripping apart flesh and bone. Amir was now ready.

He walked out of the shed, past the family car and took a bus to the Kings of Israel Square in Tel Aviv, where more than 100,000 Israelis had gathered for a demonstration in support of the peace process. It was the largest rally in Israel since 1982, when Israelis protested against their country’s invasion of Lebanon. Rabin was on stage and in a more ebullient mood than anyone could remember.

Out of the public eye, the security operation was under way to protect the prime minister. Its code name: Operation Sunrise. The special techniques for protecting VIPs in Israel are so straightforward that they can be written on one side of a sheet of paper.

But on the night of Rabin’s murder, the much-vaunted organisation was preoccupied. Evidence is emerging of recent infighting that may have weakened Shin Bet’s morale, upset its discipline and damaged its capabilities in the crucial weeks leading up to the assassination.

The trouble began six months ago when a new head of Shin Bet was appointed amid vociferous praise in the Israeli intelligence community. The fact that this man, who cannot be identified under Israeli censorship laws, spoke only broken Arabic was considered of minor importance; he had other vital qualifications, principally his expert knowledge of Jewish extremist organisations.

While at university in the 1970s he had written a thesis on Jewish fringe groups and how to deal with them from a legal point of view. Here was the man to carry Shin Bet into the new era of the peace process between Israel and the Palestinians.

But when Yaakov Perry, the outgoing head of Shin Bet, who was a close friend of Rabin’s, chose him as his heir, the result was devastating. Six section heads resigned when they realised their way to the top was blocked by the appointment, creating a serious vacuum within the organisation.

Even during Perry’s last years as director-general, signs of unease within Shin Bet had become discernible. Part of these were about Perry himself, who was nicknamed the ‘trumpeter’ for his taste for boisterous parties and wild music. There were two commissions of inquiry into Shin Bet’s activities during Perry’s tenure. But Rabin, in keeping with his customary loyalty to his friends, overlooked the reports against him.

In the words of a leading Israeli security specialist, Shin Bet had grown ‘complacent, sloppy and corrupt’. In common with many other bodies in Israel, a malaise had set in, derived from the deep divisions in Israeli society, the lack of a common goal and the pursuit of peace amid continuing terror.

None the less, it knew that an assassination was in the wind. Three weeks earlier, the heads of Shin Bet summoned leaders of the Jewish settler movement to meetings in Tel Aviv where they were urged to help build a profile of a potential assassin. They refused, saying that as leaders of their communities their involvement with the security services was inappropriate.

They assured Shin Bet that it was highly unlikely that a settler would assassinate a Jewish leader anyway. It would be better, they warned, for the security service to concentrate its energies on the Israeli heartland – the suburbs of Tel Aviv, for example.

They were right, and the view is that the new head of Shin Bet, as an expert on Jewish extremists, should have evaluated their advice better, and followed it. Like Britain’s naval guns guarding the fortress of Singapore in 1941, Shin Bet was pointing the wrong way last Saturday night.

The plain fact is that everyone knew the prime minister was in danger that night. In the days leading up to the peace demonstration, the intelligence services had publicised their fears of an attack, perhaps by sniper fire or a car bomb. The assumption was that it would come from Palestinian extremists.

There was extra surveillance around the square, with more than 1,000 policemen on duty, snipers crouched on rooftops and checks on hundreds of apartments.