скачать книгу бесплатно

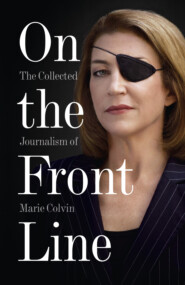

Marie with Yasser Arafat, c. 1994.

When we finally caught up with him, he owed us one. We were instantly famous in PLO ranks as the crew that had gone to Peking to see the ‘Old Man’ and been stood up. Everyone had a similar tale; this time it was not Arafat’s fault, but it usually is. People around him, a travelling entourage that is both family and staff, began helping with tips on the etiquette of living alongside him. One of my journal entries notes a word of advice from a senior aide: ‘When I break your foot, you have gone wrong.’

Arafat’s schedule is exhausting and it wears down everyone around him. Half the hotels in Tunis seem to be filled with people waiting to see Arafat. Fighters with blood rivalries meet in the lobby of the Hilton and turn their backs. Arafat maintains his own rigid personal organisation within the chaos around him. Days are for seeing to problems such as parents seeking university tuition for their children. Serious business takes place at night, dating from the time the PLO was an underground organisation. Meetings begin about 9pm and rarely end before 3am. Everyone is expected to be at Arafat’s call.

He never tells anyone, even close aides, his schedule in advance for security reasons. When you fly with him you do not know your destination until you take off. Asking a simple question at breakfast such as ‘What are you doing today?’ brings startled stares from aides and silence from Arafat.

The PLO is Arafat’s life and he expects the same commitment from everyone around him. He accepts planes and villas from Arab leaders, but remains a nomad and just out of their control. All his villas look the same – sterile, furnished with a print or two of Jerusalem, a television, some nondescript sofas and a desk. The head of the Palestinian government travels in four suitcases: one for his uniforms, one for his fax machine, one for ‘in’ and ‘out’ faxes and one for a blanket to curl up in for cat naps.

His obsessive precision can be maddening. He arranges his keffiyeh headdress meticulously every day in the same way. It must hang down his shoulder in the shape of the map of Palestine. He empties his machinegun pistol precisely as his jet takes off, carefully lining up the bullets on his tray. He marks every single fax sent to the PLO with a felt-tip red pen. But doubts begin to set in when one spends a lot of time around him. Does Arafat really have to read every single fax? Does he have to control every disbursement of funds, the purchase of an office desk in Singapore? It is Jimmy Carter as PLO leader.

Arafat is up on every detail of running the organisation, but never takes time to review policy, listen to advice or plan ahead. The PLO is run from moment to moment from Arafat’s head. The main criticism one hears in the ranks of the PLO is of this autocratic style. Arafat brooks no criticism and, as a result, many educated and independent Palestinians have opted out.

Now, when he desperately needs good advice on the workings of the western world as he tries to convince it that he is sincere in his current drive for a peaceful settlement with Israel, few around him know its ways. He himself is unsophisticated about the West, not surprisingly, as he spent most of his youth organising a resistance movement and has been banned from most of it for his adult life.

So why do Palestinians follow this unlikely leader? In person, Arafat is warm and inspires devotion. Palestinians who disagree with his views respect his devotion to the cause. He has always managed to compromise and lead by finding the highest common denominator within the fractious Palestinian movement. Arafat has no political ideology. He wants one thing: to liberate the homeland of his people. He has become more than a leader. For most Palestinians he is a symbol of their aspirations.

Arafat today is a desperate man. He is 60, has no heirs, and wants to achieve something tangible before he dies. In renouncing terrorism and recognising Israel in 1988, he played his best card and cannot understand why he has not received more support from the United States in convincing Israel to make a similar concession.

Arafat is now flying around even more obsessively than when we were filming, trying to stave off attacks from radicals within his own organisation and from Arab states who say he has given everything in return for nothing. Arafat is hoping to convince enough people to stay with him, hoping to keep the organisation together long enough, hoping to stay alive long enough, so that he can one day land his own plane in Palestine.

Home alone in Palestine: Suha Arafat

19 September 1993

When Yasser Arafat went to Washington, his wife stayed in Tunis. But she wasn’t hiding away. Marie Colvin profiles the determined Mrs Arafat.

Suha was never going to have it easy. She faced an entrenched PLO bureaucracy where proximity to Arafat meant power. But there was little they could do: by all accounts it was a love match. For the historic peace deal last week, Yasser Arafat wore a uniform, a keffiyeh that caught the slight breeze like a jib sail, and the designer stubble it might be said he pioneered. His wife Suha wore red. But while he was standing on the White House’s South Lawn, the PLO leader’s 29-year-old, French-educated wife was sitting at home in the couple’s whitewashed villa in Tunis, while the wives of Bill Clinton and Yitzhak Rabin were escorted to their seats on the South Lawn.

Arafat would no doubt have liked her to attend, but his advisers counselled him that bringing along his chic young wife would set Palestinian conservatives and radicals alike clucking away that he was treating the signing of the Palestinian–Israeli peace accord as a social event. They shuddered at the imagined sniping: Palestinians are dying in Gaza and she is parading herself in the White House.

So the Arafats were foiled. Well, not quite. She snapped on her gold earrings, donned her favourite Paris couture suit, a tasteful scarlet number decorated with jewelled buttons, and invited the CNN correspondent Richard Blystone to come and watch the ceremony chez elle. Blystone brought along a satellite dish and broadcast Suha’s thoughts and plans live to the television audience of several million watching the historic ceremony.

Standing on the mosaic portico of the marital home, she told Blystone how she was happy ‘to stay with my people in Tunis to share with them this great historical moment’.

She spoke of her future role as the first lady of Palestine in echoes of Hillary Clinton. ‘I think I have to assume great responsibilities. I must concentrate on health care for the casualties of the intifada and for all the Palestinians all over the world, to compensate for their long years of suffering.’

The public relations coup epitomised her deft manoeuvring since Arafat, a confirmed bachelor who for years had vowed he was ‘married to Palestine’, shocked the Palestinian community in July 1991 by wedding a pretty blonde less than half his age.

She recalls first hearing of her future husband when she was four years old and ‘hiding in fear’ in her family’s basement in Nablus as Israeli soldiers searched the West Bank city for a resistance leader named Arafat. In 1988, because of her fluent French and the long association of her mother Raymonda with the PLO (she founded the first Palestinian news agency in the occupied territories), Suha was asked to help out during an Arafat visit to Paris where she was living after finishing her education at the Sorbonne.

Within weeks Arafat asked her to come to Tunis as his personal assistant. Soon she was flying around the world with him and had supplanted his long-time secretary, Um Nasr. When he married Suha, there was a hair-pulling cat-fight between the two women at Arafat’s office. Um Nasr, a forty-something woman who had dedicated her life to the revolution, felt that she would make a much better wife.

Much of the resentment of Suha seems inspired not by anything she has done but rather by what she is. She is neither a traditional Arab wife in a culture that is still very conservative, nor is she the politicised revolutionary that many assumed Arafat would choose were he ever to wed. She likes French fashion and perfumes and visits Paris to stock up. Her upper-class trappings rankle among Palestinians more than the difference in age or religion (she is a Greek Orthodox Christian, he a Sunni Muslim).

For years Arafat’s nomadic existence and paucity of possessions had been a symbol of his refugee people; now Palestinians had a first lady who said: ‘It’s so difficult to take all of the luggage and go all over.’

But Suha is no bimbo. She comes from a prominent Palestinian family; her father is a wealthy banker and likes to talk of how her ancestors lived in a crusader castle. She is trying to carve out a middle role, somewhere between being a traditional wife and a public figure in her own right.

She recently took along a film crew with her to visit a Palestinian orphanage in Tunis to publicise their plight. Arafat has symbolically adopted all the children, most of whose parents are considered martyrs of the Palestinian cause. And she has founded a society to care for Palestinian children.

But unlike Hillary Clinton, who seems to tolerate Bill’s presence only because it gives her the power to implement her own programmes, Suha genuinely seems to adore Arafat. She pours him tea in the morning and nags him to rest. His schedule is less erratic these days, although he still maintains his nocturnal habits, often meeting with other PLO officials until three or four in the morning.

‘She is suffering with me,’ Arafat said last week during his Washington visit. ‘I am working 18-hour days.’

But she has given the PLO leader the chance to think of a home as well as a homeland.

Arafat thrives amid cut and thrust of peace

MIDDLE EAST

9 January 1994

For a man who was supposed to be going mad under the gruelling pressure of negotiations with Israel, Yasser Arafat, the Palestine Liberation Organisation leader, was in an extraordinarily good mood last week.

He opened a meeting of Palestinian engineers in Tunis, joking that if his political career did not work out he could always join their ranks and resume his former profession. He met for three days with a delegation of disgruntled Palestinians from the occupied territories.

He dispatched Farouq Qadoomi, the PLO foreign minister, to try to patch things up with King Hussein of Jordan. He met an all-party group of British MPs and a Gaza businessman with plans to build a floating port.

He also delivered a New Year’s Day address from his Tunis headquarters to a carphone in Yarmouk Square in Gaza; and he persuaded the executive committee, his cabinet, to stand firm in the latest contretemps with Israel over talks on the implementation of their peace accord. All the while, faxes and telephone calls flew back and forth between Arafat, his representative in Cairo, and Israel to resolve the deadlock in negotiations.

It was all in a week’s work. Arafat has changed very little in his last three decades as a Palestinian leader, much less in the three months since the peace agreement was signed in Washington. But at 64, he has been rejuvenated by Israel’s recognition of the PLO, working more hours than ever before, impatient with constraints. On New Year’s Eve he paused only for a piece of celebratory cake before signing his first working paper of the year at five minutes past midnight.

Arafat wants the peace accord to go ahead and he is twisting arms, using financial pressure, threatening those who do not agree with him and playing off internal rivalries for all that he is worth. He even bangs the table in meetings of the executive committee, and, heaven forbid, has been known to shout.

He is acting like a leader; yet this behaviour has led to charges that his style of governing is undermining the peace process and even to absurd reports that he is mentally unstable.

Perhaps this is because he has actually done something he has been criticised for not doing during his entire leadership of the Palestinian movement. It has long been the conventional wisdom that Arafat is incapable of taking the bold steps required of a leader, insisting instead on securing the consensus of even the most radical PLO faction.

When he signed the peace accord with Israel last September, Arafat took a bold and dangerous step for the first time, leaving behind anyone whom he could not convince to join him. He felt Yitzhak Rabin, the Israeli prime minister, was offering the best deal possible and that if he waited to bring along every fractious member of the PLO, that handshake on the White House lawn would still be merely a dream. In his view, those who are now accusing him of being autocratic are the same people who previously lambasted him for failing to take the initiative.

The second criticism that has lately been floated is that Arafat’s style of leadership has opened serious divisions in the PLO and that this threatens the peace process. Israel has tried to play on these divisions, making it clear for example that it would prefer to deal with Abu Mazen, the senior PLO official who signed the peace accord in Washington.

This is a serious misinterpretation of what is going on inside the PLO. In its decades of scrutiny of its enemy, Israel may have missed the forest for the trees. Although the Israeli intelligence services can identify which individual Palestinian mounted such-and-such an operation, they do not appear able to explain to their government how the PLO works.

In fact, titles mean little. Power is based on shifting internal alliances, party membership, past history, and money. Arafat is the unquestioned leader because he works the system best and because he rises above all of them as the lasting symbol of Palestinian nationalism.

Even Arafat’s most vocal opponents have not called for his replacement; they know there is nobody else who can keep the organisation united behind this peace accord. There is criticism in the PLO ranks, but this reflects the changes in Palestinian politics rather than any change in Arafat.

For years, there have been divisions along ideological lines, from the Marxist left to the Islamicists on the right. That is all irrelevant today. The divisions are now social and economic, and Arafat is having to juggle them, conducting the peace talks while he tries to put together a reliable and competent team for his new government.

He has to balance the demands of returning guerrillas and wealthy Palestinian businessmen who have made their money in the diaspora and who now want to run the economy of the new Palestinian entity; between Palestinian technicians who have worked in the West and loyal political appointees who are afraid there will be no place for them; between Palestinians inside the occupied territories, who feel they have borne the brunt of the occupation, and those returning, who feel they have sacrificed normal lives for the revolution.

The entire situation is in flux; nobody knows what his future will be, so everyone has a word for or against any move Arafat makes. But it is self-defeating for Israel to search for chinks at the top of the PLO.

There is a danger of misinterpreting events. Last week a delegation, headed by Haidar Abdel-Shafi, a soft-spoken Gaza doctor who led the PLO negotiating team in Washington, came to Tunis with a petition signed by 118 Palestinians. The visit was seen outside the PLO as an attack that could break Arafat; in fact, he had invited the delegation to discuss criticism of the way he has been proceeding with the implemention of the accord.

They talked for three days. They did not get all they wanted but Arafat agreed that Abdel-Shafi should head a ‘national debate’ on the future of the Palestinian entity. As he left, Abdel-Shafi said: ‘Arafat is monopolising power but we cannot blame Abu Ammar [Arafat] when no members of the executive committee stand up to insist on sharing this power.’

Arafat talks openly about criticism: ‘We are now facing a new era, and in this new era no doubt we can expect hesitation, criticism, worries, misunderstandings. I am not leading a herd of sheep.’

Rabin complains that dealing with Arafat is like dealing in a ‘Middle East bazaar’. Why is he surprised? Arafat is trying through any means to get the best he can out of what Palestinians see as a pretty bad deal. Arafat faced severe criticism for making too many compromises when he signed the peace agreement. Now that he has refused to compromise further, his support is growing daily.

The PLO leader is difficult to deal with. That is why he has survived. He has managed to slip through the grasp of every Arab state trying to control him – Jordan, Syria, Egypt, to name just a few. He survived in 1970 when the Jordanian king turned his army against the Palestinian guerrillas in Black September, and in 1982 when Israel turned its might against him in Lebanon.

Rabin, when he shook Arafat’s hand in Washington, seemed to be acknowledging that no matter how much he despised Arafat, the PLO leader was the only possible partner for peace. Since then, the Israeli prime minister has conducted peace negotiations not as if he was dealing with a partner but with an enemy that must be controlled and contained to the most minute detail. The last Israeli negotiating document stipulated that there should be opaque glass between the partitions at crossing points.

In making such details the focus of negotiations, and in seeking to divide and conquer, Israel has lost sight of what it agreed to do in Washington – make peace with the PLO, led by Arafat, for better or for worse. Rabin should begin dealing again with Arafat as a partner in peace. And the judgement of Arafat should be left to when it really matters, when he enters his homeland and heads the government.

Rabin last week told his cabinet: ‘We will let them sweat.’ Who? The PLO?

‘Look at me,’ said Arafat on Friday night. ‘I’m not sweating.’

Libya

Frightened Libyans await the next blow: sanctions

TRIPOLI

19 April 1992

The omens had been bad all week. Colonel Muammar Gadaffi lay tucked up in bed with tonsillitis, UN sanctions had closed off the country and Russian military advisers haggled for suitcases in the souk before making a break for the border. When the chill Hamsin wind blew in off the desert it seemed that even the weather was conspiring against the Libyan leader.

Out on the streets, Libyans felt anxious, vulnerable and isolated. While the sanctions imposed last week caused inconvenience not hardship, they were a severe psychological blow. Once again the Libyan people felt trapped in confrontation with the West. They are dreading the next turn of the screw. Oil sanctions? Another air strike?

The disgruntled middle-class expresses resentment only in private. At a dinner party in Tripoli last week guests lamented how Libya’s wealth had been frittered away, siphoned off to military and revolutionary movements all over the world.

‘We are only 4m Libyans and we export 1m barrels of oil a day,’ a businessman said. ‘We could be like Saudi Arabia. Instead look at us.’

His expansive wave of disgust took in the shabby clothes of his countrymen, the dirty hospitals where patients often sleep two to a bed and the vast, grimy supermarkets like the Souk al Jumaa that stand empty or display rows of plastic candelabra from Romania.

Such anger is, of course, impotent because Gadaffi brooks no opposition. After rumblings of discontent, he has reinstated his ‘revolutionary committees’, the young shock troops that were stood down three years ago after an outcry over their ‘excesses’.

The escalating tension evoked memories of the weeks leading up to the American bombing of Tripoli and Benghazi in 1986, during which at least 70 civilians, including Gadaffi’s adopted daughter, were killed. On television, announcers condemn George Bush as ‘unjust’ and read telegrams of support. ‘The crusaders think they can humiliate these people, the Libyan people, but they are mistaken,’ raged one Muslim preacher in a televised sermon. ‘We will bend our heads only to Allah.’

The appeals may be the same but there is a key difference. Gone is the fury of the organised daily demonstrations; one protest in Tripoli’s Green Square drew only about 50 young men who danced to Algerian rai music before drifting away in good humour.

Gadaffi was chastened by the bombing and has so far forsworn the revolutionary rhetoric of 1986. As he lay on his sickbed, he was no doubt pondering the dilemma of whether to surrender the two Libyan intelligence agents accused of planting the bomb that exploded aboard a Pan Am jet over Lockerbie three years ago, killing 270 people.

Although his old friend Yasser Arafat, the PLO leader, returned to Tripoli saying ‘I must stand by Libya and my brother Gadaffi’, solidarity is in short supply. The Soviet Union, Gadaffi’s long-time backer, is no more and Arab leaders refused landing permission to the planes he sent out in defiance of the UN sanctions.

It is no easy choice. Should Gadaffi surrender the accused men unconditionally, they may implicate more senior Libyan officials and prompt further demands. ‘If you hand them over, you are lost,’ one Arab envoy advised him last week. ‘The Americans will come back with a list of 100 names, then the name of Abdelsalam Jalloud [Gadaffi’s second-in-command], then your name.’

Jalloud, a rough-spoken major and Gadaffi’s close comrade since they seized power with a gang of young officers in 1969, is said to be arguing fiercely against surrendering the two suspects, both members of his tribe.

For many Libyans, fed up with 22 years of revolution and crisis, the new openness of Gadaffi’s own brand of perestroika now appears under threat. Should Gadaffi play a wrong move in his poker game his people are unlikely to forgive him, even though few think the West’s demands are just.

His low-key response suggests that he has been seeking a compromise behind the scenes to have sanctions against air travel, diplomats and arms lifted. He does not wish to repeat the mistake of Saddam Hussein, and knows that taking foreign workers as a ‘human shield’ would only unleash a violent reaction.

But Libyans are disillusioned. Today only the revolutionary committee apparatchiks believe the new sign on the road to the airport: ‘We are all Muammar Gadaffis.’

Adie’s minder cracks up: Saleh

TRIPOLI

26 April 1992

Saleh is a broken man, his health uncertain, his job insecure. But his plight has little to do with the political pressures on the beleaguered Libyan regime that employs him. Recovering from a nervous breakdown, Saleh sums up his woes in two words: Kate Adie.

Assigned as a government ‘minder’ to the roving doyenne of the BBC, Saleh looks back on it all from his sickbed with the horror of a man plucked from the deck of a sinking ship in shark-infested waters. ‘Oh dear,’ he moaned. ‘Kate Adie has been very bad for my health. I have very tender nerves.’

Adie, a veteran of Tiananmen Square, Tripoli and the Gulf, succeeded where sanctions had failed: she had brought the government to its knees.

The extent of the Libyan anguish emerged last week in an extraordinary telex to the BBC, in which Tripoli bemoaned the pugnacious temperament of Adie and pleaded for her to be withdrawn.

‘All our attempts to obtain a common and satisfactory solution were gone with the wind,’ lamented the telex. ‘We are demanding never ever send Kate Adie to Libya whatever the reasons are.’

By that stage, Saleh was at his wits end. Wandering into the lobby of the Bab al-Bahar hotel, he fainted. Coming round, he muttered, ‘If you ask me to choose Kate Adie or prison I would not hesitate to choose the prison.’

Grimacing as he relived their last encounter, in a crowded hotel lobby, Saleh said: ‘She said she should be filming demonstrations. I told her there were no demonstrations or clashes. But she insisted we find some.’

Deploying ruthless hyperbole, Adie said Libya was treating the foreign press ‘in a manner that had gone out of fashion with Stalin’.

Saleh respectfully suggested Adie should leave. But that was like waving a red flag at a bull. ‘If you are throwing me out it will be very bad for your country,’ she stormed.

Saleh went on: ‘I felt shy, so small, like an ant. I am from a good family but she was treating me as if I was a slave or an illegal boy [bastard]. But because of her age I am not allowed to shout or attack her. I must treat her like a mother or a grandmother.’

His next step was to assign an underling to Adie. The colleague was soon on the phone. ‘He was calling me all the time and begging me to release him. He said, “Saleh what have you done to me?”’

The ministry adopted new tactics. The BBC was banned from filming, as were other television crews. But Adie soon found her way round that. ‘Kate Adie said I had to choose between going to the souk [market] with her or have her shout at me. I took her to the souk,’ recalls Omar, the replacement minder.

As a last resort, the information ministry hosted ‘a farewell dinner’ in which, it was hoped, Adie would get the message. The next day, to their horror, officials received intelligence that she had embarked upon another embroidery square, her favourite method of whiling away time.

In the end, she left on Thursday. ‘We have sanctions,’ said one official, ‘but even worse is Kate Adie.’

Lockerbie drama turns to farce

3 October 1993

Although Muammar Gadaffi, the Libyan leader, is on the brink at last of surrendering the two men suspected of the Lockerbie bombing, justice is far from being done.

After one of the biggest international investigations ever mounted, the expenditure of more than £12 million of British taxpayers’ money, and interviews with 16,000 witnesses in 53 countries, most of the evidence indicates that those who made the decision to bomb Pan Am flight 103 will be nowhere near the court.

Libyan sources said yesterday that, under threat of increased United Nations sanctions, Gadaffi had decided to hand over the suspects for trial in Scotland.

Few who have investigated the case think these men, Abdel Baset al-Megrahi and Al Amin Khalifa Fhimah, initiated or planned the operation.

They are low-level intelligence operatives. One is obviously slow-witted. They are accused of smuggling a suitcase bomb aboard a plane from Malta to Frankfurt, where it was loaded aboard the Pan Am flight that exploded over Lockerbie, killing 270 people, at Christmas 1988.