Полная версия

Полная версияLocal Color

“Some doings, eh, Flying Jenny?”

Whereat the singer, thus jovially addressed, conferred a wink and a grin upon him and shouted back: “Don’t be so blamed formal – just call me Jane!” and then skillfully picked up the tune again and kept right on tenoring. They were all still enmeshed and in all unison enriching the pent-up confines of their car with close harmonies when the train began to check up bumpingly, and advised by familiar objects beginning to pass the windows Mr. Birdseye realised that they approached their destination. It didn’t seem humanly possible that so much time had elapsed with such miraculous rapidity, but there was the indisputable evidence in Langford’s Real Estate Division and the trackside warehouses of Brazzell Brothers’ Pride of Dixie fertilizer works. From a chosen and accepted comrade he now became also a guide.

“Fellows!” he announced, breaking out of the ring, “we’ll be in in just a minute – this is Anneburg!”

Coincidentally with this announcement the conductor appeared at the forward end of the car and in a word gave confirmatory evidence. Of the car porter there was no sign. Duty called him to be present, but prudence bade him nay. He had discretion, that porter.

The song that was being sung at that particular moment – whatever it was – was suffered to languish and die midway of a long-drawn refrain. There was a scattering of the minstrels to snatch up suit cases, bags and other portable impedimenta.

“I’ll ride up to the hotel with you,” suggested Mr. Birdseye, laying a detaining hand upon the master’s elbow. “If I get a chance there’s something I want to tell you on the way.” He was just remembering he had forgotten to mention that treacherous soft spot back of centre field.

“You bet your blameless young life you’ll ride with us!” answered back the other, reaching for a valise.

“What? Lose our honoured and esteemed reception committee now? Not a chance!” confirmed an enormous youth whose bass tones fitted him for the life of a troubadour, but whose breadth of frame qualified him for piano-moving or centre-rushing. With a great bear-hug he lifted Mr. Birdseye in his arms, roughly fondling him.

“You’re going to the Hotel Balboa, of course,” added Mr. Birdseye, regaining his feet and his breath as the caressing grip of the giant relaxed.

“Hotel Balboa is right, old Pathfinder.”

“Then we’d all better take the hotel bus uptown, hadn’t we?”

“Just watch us take it.”

“I’ll lay eight to five that bus has never been properly taken before now.”

“But it’s about to be.” He who uttered this prophecy was the brisk youngster who had objected to being designated by so elaborated a title as Flying Jenny.

“All out!”

Like a chip on the crest of a mountain torrent Mr. Birdseye was borne down the car steps as the train halted beneath the shed of the Anneburg station. Across the intervening tracks, through the gate and the station and out again at the far side of the waiting room the living freshet poured. As he was carried along with it, the Indian being at his right hand, the orange thrower at his left, and behind him irresistible forces ramping and roaring, Mr. Birdseye was aware of a large crowd, of Nick Cornwall, of others locally associated with the destinies of the Anneburg team, of many known to him personally or by name, all staring hard, with puzzled looks, as he went whirling on by. Their faces were visible a fleeting moment, then vanished like faces seen in a fitful dream, and now the human ground swell had surrounded and inundated a large motorbus, property of the Hotel Balboa.

Strong arms reached upward and, as though he had been a child, plucked from his perch the dumfounded driver of this vehicle, with a swing depositing him ten feet distant, well out of harm’s way. A youth who plainly understood the mystery of motors clambered up, nimble as a monkey, taking seat and wheel. Another mounted alongside of him and rolled up a magazine to make a coaching horn of it. Another and yet another followed, until a cushioned space designed for two only held four. As pirates aforetime have boarded a wallowing galleon the rest of the crew boarded the body of the bus. They entered by door or by window, whichever chanced to be handier, first firing their hand baggage in with a splendid disregard of consequences.

In less than no time at all, to tallyho tootings, to whoops and to yells and to snatches of melody, the Hotel Balboa bus was rolling through a startled business district, bearing in it, upon it and overflowing from it full twice as many fares as its builder had imagined it conceivably would ever contain when he planned its design and its accommodations. Side by side on the floor at its back door with feet out in space, were jammed together Mr. J. Henry Birdseye and the aforesaid blocky chieftain of the band. Teams checked up as the caravan rolled on. Foot travellers froze in their tracks to stare at the spectacle. Birdseye saw them. They saw Birdseye. And he saw that they saw and felt that be the future what it might, life for him could never bring a greater, more triumphant, more exultant moment than this.

“Is that the opera house right ahead?” inquired his illustrious mate as the bus jounced round the corner of Lattimer Street.

“No, that’s the new Second National Bank,” explained Mr. Birdseye between jolts. “The opera house is four doors further down – see, right there – just next to where that sign says ‘Tascott & Nutt, Hardware.’”

Simultaneously those who rode in front and atop must likewise have read the sign of Tascott & Nutt. For the bus, as though on signal, swerved to the curb before this establishment and stopped dead short, and in chorus a dozen strong voices called for Mr. Nutt, continuing to call until a plump, middle-aged gentleman in his shirt sleeves issued from the interior and crossed the sidewalk, surprise being writ large upon his face. When he had drawn near enough, sinewy hands stretched forth and pounced upon him, and as the bus resumed its journey he most unwillingly was dragged at an undignified dogtrot alongside a rear wheel while strange, tormenting questions were shouted down at him:

“Oh, Mr. Nutt, how’s your dear old coco?”

“And how’s your daughter Hazel? – charming girl, Hazel!”

“And your son, Philip Bertram? Don’t tell me the squirrels have been after that dear Phil Bert again!”

“You’ll be careful about the chipmunks this summer, won’t you, Mr. Nutt – for our sakes?”

“Old Man Nutt is a good old soul.”

But this last was part of a song, and not a question at all.

The victim wrested himself free at last and stood in the highroad speechless with indignation. Lack of breath was likewise a contributing factor. Mr. Birdseye observed, as they drew away from the panting figure, that the starting eyes of Mr. Nutt were fixed upon him recognisingly and accusingly, and realised that he was in some way being blamed for the discomfiture of that solid man and that he had made a sincere enemy for life. But what cared he? Meadow larks, golden breasted, sat in his short ribs and sang to his soul.

And now they had drawn up at the Hotel Balboa, and with Birdseye still in the van they had piled off and were swirling through the lobby to splash up against the bulkhead of the clerk’s desk, behind which, with a wide professional smile of hospitality on his lips, Head Clerk Ollie Bates awaited their coming and their pleasure.

“You got our wire?” demanded of him the young manager. “Rooms all ready?”

“Rooms all ready, Mister – ”

“Fine and dandy! We’ll go right up and wash up for lunch. Here’s the list – copy the names onto the register yourself. Where’s the elevator? Oh, there it is. All aboard, boys! No, wait a minute,” countermanded this young commander who forgot nothing, as he turned and confronted Mr. Birdseye. “Before parting, we will give three cheers for our dear friend, guide and well-wisher, Colonel Birdseye Maple. All together:

“Whee! Whee! Whee!”

The last and loudest Whee died away; the troupe charged through and over a skirmish line of darky bell hops; they stormed the elevator cage. Half in and half out of it their chief paused to wave a hand to him whom they had just honoured.

“See you later, Colonel,” he called across the intervening space. “You said you’d be there when we open up, you know.”

“I’ll be there, Swifty, on a front seat!” pledged Mr. Birdseye happily.

The overloaded elevator strained and started and vanished upward, vocal to the last. In the comparative calm which ensued Mr. Birdseye, head well up, chest well out, and thumbs in the arm openings of a distended waistcoat, lounged easily but with the obvious air of a conqueror back toward the desk and Mr. Ollie Bates.

“Some noisy bunch!” said Mr. Bates admiringly. “Say, J. Henry, where did they pick you up?”

“They didn’t pick me up, I picked them up – met ’em over at Barstow and rode in with ’em.”

“Seems like it didn’t take you long to make friends with ’em,” commented Mr. Bates.

“It didn’t take me half a minute. Easiest bunch to get acquainted with you ever saw in your life, Ollie. And kidders? Well, they wrote kidding – that’s all – words and music. I wish you could a-seen them stringing old man ’Lonzo Nutt down the street! I like to died!” He unbent a trifle; after all, Mr. Bates was an old friend. “Say, Ollie, that gang won’t do a thing to our little old scrub team this afternoon, with Long Leaf Pinderson pitching. I saw him in action – with oranges. He – ”

“Say, listen, J. Henry,” broke in Mr. Bates. “Who in thunder do you think that gang is you’ve been associating with?”

“Think it is? Who would it be but the Moguls?”

“Moguls?”

A convulsion seized and overcame Mr. Bates. He bent double, his distorted face in his hands, his shoulders heaving, weird sounds issuing from his throat. Then lifting his head, he opened that big mouth of his, afflicting the adjacent air with raucous and discordant laughter.

“Moguls! Moguls! Say, you need to have your head looked into. Why, J. Henry, the Moguls came in on the twelve-forty-five and Nick Cornwall and the crowd met ’em and they’re down to the Hotel Esplanade right this minute, I reckon. We tried to land ’em for the Balboa, but it seemed like they wanted a quiet hotel. Well, they’ll have their wish at the Esplanade!”

“Then who – then who are these?”

It was the broken, faltering accent of Mr. Birdseye, sounded wanly and as from a long way off.

“These? Why, it’s the College Glee Club from Chickasaw Tech., down in Alabama, that’s going to give a concert at the opera house to-night. And you thought all the time you were with the Moguls? Well, you poor simp!”

In addition to simp Mr. Bates also used the words boob, sucker, chunk of Camembert and dub in this connection. But it is doubtful if Mr. Birdseye heard him now. A great roaring, as of dashing cataracts and swirling rapids, filled his ears as he fled away, blindly seeking some sanctuary wherein to hide himself from the gaze of mortal man.

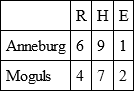

Remaining to be told is but little; but that little looms important as tending to prove that truth sometimes is stranger than fiction. With Swifty Megrue coaching, with Magnus, the Big Chief, backstopping, with Pinderson, master of the spitball, in the box twirling, nevertheless and to the contrary notwithstanding, the Anneburg team that day mopped up, the score standing:

CHAPTER X

SMOOTH CROSSING

On this voyage the Mesopotamia was to sail at midnight. It was now, to be precise about it, eleven forty-five P. M. and some odd seconds; and they were wrestling the last of the heavy luggage aboard. The Babel-babble that distinguishes a big liner’s departure was approaching its climax of acute hysteria, when two well-dressed, youngish men joined the wormlike column of eleventh-hour passengers mounting a portable bridge labelled First Cabin which hyphenated the strip of dark water between ship and shore. They were almost the last persons to join the line, coming in such haste along the dock that the dock captain on duty at the foot of the canvas-sided gangway let them pass without question.

Except that these two men were much of a size and at a first glance rather alike in general aspect; and except that one of them, the rearmost, bore two bulging handbags while the other kept his hands muffled in a grey tweed ulster that lay across his arms, there was nothing about them or either of them to distinguish them from any other belated pair of men in that jostling procession of the flurried and the hurried. Oh, yes, one of them had a moustache and the other had none.

Indian file they went up the gangway and past the second officer, who stood at the head of it; and still tandem they pushed and were pushed along through the jam upon the deck. The second man, the one who bore the handbags, gave them over to a steward who had jumped forward when he saw them coming. He hesitated then, looking about him.

“Come on, it’s all right,” said the first man.

“How about the tickets? Don’t we have to show them first?” inquired the other.

“No, not now,” said his companion. “We can go direct to our stateroom.” The same speaker addressed the steward:

“D-forty,” he said briskly.

“Quite right, sir,” said the steward. “D-forty. Right this way, sir; if you please, sir.”

With the dexterity born of long practice the steward, burdened though he was, bored a path for himself and them through the crowd. He led them from the deck, across a corner of a big cabin that was like a hotel lobby, and down flights of broad stairs from B-deck to C and from C-deck to D, and thence aft along a narrow companionway until he came to a cross hall where another steward stood.

“Two gentlemen for D-forty,” said their guide. Surrendering the handbags to this other functionary, he touched his cap and vanished into thin air, magically, after the custom of ancient Arabian genii and modern British steamship servants.

“’Ere you are, sirs,” said the second steward. He opened the door of a stateroom and stood aside to let them in. Following in behind them he deposited the handbags in mathematical alignment upon the floor and spoke a warning: “We’ll be leavin’ in a minute or two now, but it’s just as well, sir, to keep your stateroom door locked until we’re off – thieves are about sometimes in port, you know, sir. Was there anything else, sir?” He addressed them in the singular, but considered them, so to speak, in the plural. “I’m the bedroom steward, sir,” he added in final explanation.

The passenger who had asked concerning the tickets looked about him curiously, as though the interior arrangement of a steamship stateroom was to him strange.

“So you’re the bedroom steward,” he said. “What’s your name?”

“Lawrence, sir.”

“Lawrence what?”

“I beg your pardon, sir?” said the steward, looking puzzled.

“He wants to know your first name,” explained the other prospective occupant of D-forty. This man had sat himself down upon the edge of the bed, still with his grey ulster folded forward across his arms as though the pockets held something valuable and must be kept in a certain position, just so, to prevent the contents spilling out.

“’Erbert Lawrence, sir, thank you, sir,” said the steward, his face clearing, “I’ll be ’andy if you ring, sir.” He backed out. “Nothing else, sir? I’ll see to your ’eavy luggage in the mornin’. Will there be any trunks for the stateroom?”

“No trunks,” said the man on the bed. “Just some suitcases. They came aboard just ahead of us, I think.”

“Right, sir,” said the accommodating Lawrence. “I’ll get your tickets in the morning and take them to the purser, if you don’t mind. Thank you, sir.” And with that he bowed himself out and was gone.

As the door closed behind this thoughtful and accommodating servitor the fellow travellers looked at each other for a moment steadily, much as though they might be sharers of a common secret that neither cared to mention even between themselves. The one who stood spoke first:

“I guess I’ll go up and see her pull out,” he said. “I’ve never seen a ship pull out; it’s a new thing to me. Want to go?”

The man nursing the ulster shook his head.

“All right, then,” said the first. He pitched his own topcoat, which he had been carrying under his arm, upon the lone chair. “I’ll be back pretty soon.” He glanced keenly at the one small porthole, looked about the stateroom once more, then stepped across the threshold and closed the door. The lock clicked.

Left alone, the other man sat for a half minute or so as he was, with his head tilted forward in an attitude of listening. Then he stood up and with a series of shrugging, lifting motions, jerked the ulster forward so that it slipped through the loop of his arms upon the floor. Had the efficient Lawrence returned at that moment it is safe to say he would have sustained a profound shock, although it is equally safe to say he would have made desperate efforts to avoid showing his emotions. The man was manacled. Below his white shirt-cuffs his wrists were encircled by snug-fitting, shiny bracelets of steel united by a steel chain of four short links. That explained his rather peculiar way of carrying his ulster and his decidedly awkward way of ridding himself of it.

He stepped across the room and with his coupled hands tried the knob of the door. The knob turned, but the bolt had been set from the outside. He was locked in. With his foot he dragged forward a footstool, kicking it close up against the panels so that should any person coming in open the door suddenly, the stool would retard that person’s entrance for a moment anyway. He faced about then, considering his next move. The circular pane of thick glass in the porthole showed as a black target in the white wall; through it only blankness was visible. D-deck plainly was well down in the ship’s hull, below the level of promenades and probably not very far above the waterline. Nevertheless, the handcuffed man crossed over and drew the short silken curtains across the window, making the seclusion of his quarters doubly secure.

Now, kneeling upon the floor, he undid the hasps of the two handbags, opened them and began rummaging in their cluttered depths. Doing all these things, he moved with a sureness and celerity which showed that he had worn his bonds for an appreciable space of time and had accustomed himself to using his two hands upon an operation where, unhampered, he might have used one or the other, but not both at once. His chain clinked briskly as he felt about in the valises. From them he first got out two travelling caps – one a dark grey cap, the other a cap of rather a gaudy check pattern; also, a plain razor, a safety razor and a box of cigars. He examined the safety razor a moment, then slipped it back into the flap pocket where it belonged; took a cigar from the box and put the box back into the grip; tried on first one of the travelling caps and then the other, and returned them to the places from which he had taken them; and reclosed and refastened the grips themselves. But he took the other razor and dropped it in a certain place, close down to the floor at the foot of one of the beds.

He shoved the footstool away from the door, and, after dusting off his knees, he went and stood at the porthole gazing out into the night through a cranny in the curtains. The ship no longer nuzzled up alongside the dock like a great sucking pig under the flanks of an even greater mother-sow; she appeared to stand still while the dock seemed to be slipping away from her rearward; but the man who looked out into the darkness was familiar enough with that illusion. With his manacled hands crossed upon his waistcoat and the cigar hanging unlighted between his lips, he watched until the liner had turned and was swinging down stream, heading for the mouth of the river and the bay.

He lit the cigar, then, and once more sat himself down upon the edge of the bed. He puffed away steadily. His head was bent forward and his hands dangled between his knees in such ease as the snugness of the bracelets and the shortness of the chain permitted. Looking in at him you would have said he was planning something; that he was considering various problems. He was still there in that same hunching position, but the cigar had burned down two-thirds of its length, when the lock snicked a warning and his companion re-entered, bearing a key with which he relocked the door upon the inner side.

“Well,” said the newcomer, “we’re on our way.” There was no reply to this. He took off his derby hat and tossed it aside, and began unbuttoning his waistcoat.

“Making yourself comfortable, eh?” he went on as though trying to manufacture conversation. The manacled one didn’t respond. He merely canted his head, the better to look into the face of his travel mate.

“Say, look here,” demanded the new arrival, his tone and manner changing. “What’s the use, your nursing that grouch?”

Coming up the gangway, twenty minutes before, they might have passed, at a casual glance, for brothers. Viewed now as they faced each other in the quiet of this small room such a mistake could not have been possible. They did not suggest brothers; for all that they were much the same in build and colouring they did not even suggest distant cousins. About the sitting man there were abundant evidences of a higher and more cultured organism than the other possessed; the difference showed in costume, in manner, in speech. Even wearing handcuffs he displayed, without trying to do so, a certain superiority in poise and assurance. In a way his companion seemed vaguely aware of this. It seemed to make him – what shall I say? – uneasy; maybe a bit envious; possibly arousing in him the imitative instinct. Judging of him by his present aspect and the intonations of his voice, a shrewd observer of men and motives might have said that he was amply satisfied with the progress of the undertaking which he had now in hand, but that he lately had ceased to be entirely satisfied with himself.

“Say, Bronston,” he repeated, “I tell you there’s no good nursing the grouch. I haven’t done anything all through this matter except what I thought was necessary. I’ve acted that way from the beginning, ain’t I?”

“Have you heard me complain?” parried the gyved man. He blew out a mouthful of smoke.

“No, I haven’t, not since you made the first kick that day I found you out in Denver. But a fellow can’t very well travel twenty-five hundred miles with another fellow, sharing the same stateroom with him and all that, without guessing what’s in the other fellow’s mind.”

There was another little pause.

“Well,” said the man upon the bed, “we’ve got this far. What’s the programme from this point on regarding these decorations?” He raised his hands to indicate what he meant.

“That’s what I want to talk with you about,” answered the other. “The rest of the folks on this boat don’t know anything about us – not a blessed thing. The officers don’t know – nor the crew, nor any of the passengers, I reckon. To them we’re just two ordinary Americans crossing the ocean together on business or pleasure. You give me your promise not to make any breaks of any sort, and I’ll take those things off you and not put them on again until just before we land. You know I want to make this trip as easy as I can for you.”

“What earthly difference would it make whether I gave you my promise or not? Suppose, as you put it, I did make a break? Where would I break for out in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean? Are you still afraid of yourself?”

“Certainly not; certainly I ain’t afraid. At that, you’ve been back and forth plenty of times across the ocean, and you know all the ropes on a ship and I don’t. Still, I ain’t afraid. But I’d like to have your promise.”

“I won’t give it,” said he of the handcuffs promptly. “I’m through with making offers to you. Four days ago when you caught up with me, I told you I would go with you and make no resistance – make no attempt to get away from you – if you’d only leave my limbs free. You knew as well as I did that I was willing to waive extradition and go back without any fuss or any delay, in order to keep my people in this country from finding out what a devil’s mess I’d gotten myself into over on the other side. You knew I was not really a criminal, that I’d done nothing at all which an American court would construe as a crime. You knew that because I was an American the British courts would probably be especially hard upon me. And you knew too – you found that part out for yourself without my telling you – that I was intending to go back to England at the first chance. You knew that all I needed was a chance to get at certain papers and documents and produce them in open court to prove that I was being made a scapegoat; you knew that if I had just two days free on British soil, in which to get the books from the place those lying partners of mine hid them, I could save myself from doing penal servitude. That was why I meant to go back of my own accord. That was why I offered to give you my word of honour that I would not attempt to get away. Did you listen? No!”