Полная версия:

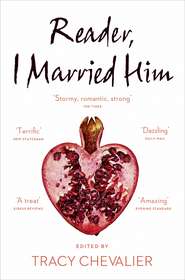

Reader, I Married Him

What I hated most was the way she made herself milk and water, a dish of whey for anyone to drink at, sip sop sip sop, when what she truly wanted was to be a blade through the heart of us. I knew it but the rest were dumb and blind. The old lady loved the sip sop. As for the little girl, she was taken by her, like a baby taken for a changeling.

My poor lady’s skull showed an enlarged Organ of Destructiveness. Dr Gallion passed his fingers over the place and repeated the words. He nodded and Mr R nodded with him, the two gentlemen solemn together now while my lady bent her head and her hair slid over her shoulders. The doctor had loosened it from the knots and coils she wore, the better to get at her.

In such a case as this, the doctor said, it would be wise to shave the head entire, the more clearly to see how the organs display themselves.

I rubbed oil into the bristle that sprouted from my lady’s scalp, so that it would grow more quickly. She was bewildered at the loss of her hair. She would raise her hand as if to touch the knot that sat at her nape, and find it gone, and then her hand would waver. I would give her a little laudanum and she would rock herself and seem to find comfort in it.

The pale one thinks she has the measure of us all. Up and down the garden she goes in the shadows of evening. She ticks us off in her steps. The old lady. Mr R. The little girl. The guests who come and go. She would tick me off too but she only knows my name. She asked it and they told her: Grace Poole.

I am a strong creature with a pot of porter. I receive excellent wages. I am so turned and turned about that if I saw a snowdrop push its way out of the earth I would stamp on it.

She was brought here to dig the frippery out of the little girl, so that the child might take her proper station in life.

Less noise there, Grace.

I can make a noise if I want. They know that. I have not yet lost my voice. If I spoke out I’d tell the pale one a story she wouldn’t soon forget.

Long ago he married my lady and they were Mr and Mrs R. Amativeness is what the doctor called it. This was long before the snowdrop raised its head, but the creature with the porter was already here. Me. Fifteen was I? As old as my tongue and a little older than my teeth. I was a lovely flashing bit of a girl then. I could stop men of thirty dead in their tracks as they ploughed. I made the air so thick around me they seemed to wade or drown in it. I was Grace Poole.

I stopped him dead in his tracks. I did not care for my lady then or know her. She did not come downstairs. They said she was nervous. To me she was a foreign land where I never wished to go.

Grace Poole, he said to me, and I saw him tremble. Is that your name?

I tilted the water I was carrying so that the jug rested on my hip. I said nothing. Let him look, I thought, and I shall look back at him.

I had an attic then. A slip of a room all white with sunlight and almost bare, but there was a bed in it. He was older than me but not by so much. He had married young and they said he was unhappy. I thought of nothing then except having him.

I dare say he had never lain down on such a bed in his life. We had to put our hands over each other’s mouths so as not to cry out.

Grace Poole, he said when I released him. Grace Poole. It was the most beautiful thing I had ever heard: my own name. No one heard and no one came.

No man likes a big belly. I carried mine to a place he procured for me. He told me that he would provide for the child and give it a station in life, and I would come back to Thornfield. It was more than I expected. He was a fox because it was his nature, but he kept his word about the child. I did not resist when it was born and taken by a wet nurse, to go far away to a better place.

I took a fever when it was gone and the room stank so that even the nurse who tended me held up a handkerchief over her face, but I did not die. I pitted and spotted and what got up from the bed was no longer the old Grace Poole but the beginning of the creature you see presently. I grew as strong as you like. I came back to Thornfield and took a taste for nursing, as perhaps he had foreseen.

I did not want anyone to look at me. And there she is, the pale one, bursting with it, every inch of her chill little flesh shouting: Look at me.

She will never stand before him as I did and look back at him, and make him come to her. She hunts in another fashion.

So I came to nurse my lady here. She would not eat so I fed her from a spoon. She would not speak so I learned her gestures and what they meant. I brushed her hair, which was thick and soft and long enough to touch the ground when she sat. It took an hour sometimes to brush her hair, to plait it and coil it into the knot she liked. When it was finished she would put up her hands to touch it and she would be satisfied. She liked her laudanum flavoured with cinnamon and not with saffron, which was what they gave her at first. Another thing she liked was a bit of red satin ribbon which she would wrap around her fingers and rub against her cheek as she rocked herself, and at those times although she never spoke she would hum and I would think: Perhaps she is content.

Each morning: porridge with cream and syrup, so that even a little of it will fatten her. Sometimes she will take a dish of tea; other times she will dash it from my hand. But no matter how fiercely she smashes china, she never touches me. There has been long discussion over whether or not she should take meat. It is heating. It inflames the passions. She is allowed only a very little beef. I make broth for her myself, out of bones she likes to crack with her teeth when they are cooked so that the marrow is ready to drip out of them. She will eat toast sometimes, as long as it is cut so fine it splinters to pieces if the butter is hard. On the days when she puts her lips together and will not swallow, I know better now than to persuade her. I take out my two packs of cards and make them flicker down into heaps over and over. It soothes her.

But now here we are: the old lady, the snowdrop, the little girl, Mr R, my lady and the creature with the porter. Me. The little girl has come back from France and she does not know me. She peeps and cheeps about the house with her high French voice and her dancing slippers. In the kitchen they say that she is the child of a French opera dancer that Mr R has kept in France. Some say that the opera dancer is dead, others that he has tired of her. They are used to me going in and out without partaking of the conversation, as I fetch and carry my lady’s food and drink. They call me Mrs Poole and none of them will cross me. Richard the footman visited London when he was a boy and he says he would rather have charge of the entire menagerie at Exeter ’Change than be left alone with Mrs R as I am. All I will ever own is that my lady has her ways.

If the pale one had not come to this house we should all have kept on safe. The little girl did not know me. I was content with that. I liked to see her flutter about the house in her lace and silk, and dance in front of the mirror. I was no more the Grace Poole who laid herself down on the narrow bed in the sunlit attic than I was Mr R himself. I rose up from childbed another woman and I am that woman now. I have no child but I have Mrs R. Let the little girl skip where she wants and peep out her French phrases and grow up to a suitable station. But this pale one has come here, loitering in our lanes and uncannily stealing what does not belong to her. And now here is my lady disturbed night after night, murmuring and rocking. No one knows what senses she has. Sometimes I see thoughts whisk in her eyes that I would never dare to see the bottom of, and I know that Mr R will not come here again and face her.

Mr R knows that I will never leave her. We should have been safe, if that one had never come here. Of course she wants my lady gone. She spins out words in her head like a spider. She will have us all wrapped tight. I see him walking in the garden, and her walking after him, so sly and small and neat that you would never think twice of it. She calls my lady a madwoman and a danger, and he listens. She says these words and he listens, in spite of all the years I have kept my lady safe and she has never troubled him. She wants my lady gone.

She may marry Mr R. She may take him for all that there is left in him. She will never stop him dead and make him tremble all over, as I did, before he ever touched me. She can do no harm to the little girl. With her bright black eyes and her dancing feet the child will go where she chooses, and by the time she is fifteen she will turn the air around her thick with longing. We will all be what we are again.

But you could put your hand through Miss Eyre and never grasp her. I know what she is. There she sits in the window seat, folded into the shadows, watching us. She has come here hunting. I have seen how she devours red meat when she thinks herself alone. She wants my lady gone. She will have my lady put away like a madwoman. Her hair cut again, her ribbon taken and nothing to comfort her. The doctors will measure her skull with callipers.

The pale one may hunt but she must not touch my lady. I read in my Bible with my good candles burning late. St Paul says that it is better to marry than to burn, but there is marriage and there is marriage. Sometimes it may be better to burn.

I will make my lady a custard, which I can do better than any cook in England. I will sit on my stool beside her and hold the spoon to her lips. Sometimes I chirrup as if she were a bird, to make her open her lips. She holds her red ribbon in her lap and her eyes meet mine and then she does open, she does take the spoon of custard into her mouth and she does swallow.

DANGEROUS DOG

KIRSTY GUNN

IN A WAY, I could start this short story with a dream I had last night in which I was attacked by two rogue Labradors who’d seemed sweet at first but then turned mean. This was at the gates of the park where I normally go running, and the Labradors went for me right there, one biting my hand, holding on and not letting go, the other mauling my clothing. I could start with that, I suppose, because the same park features heavily in the story I want to write and it works as a nice “gateway to narrative” – a phrase Reed has taught me and the kind of thing I come out with now as casually as terms like “core muscles” or “aerobic as opposed to muscular fitness”, which have been a natural part of my professional vocabulary as a fitness trainer and personal body-development coach.

So yes, I could start with that dream, with me reaching down to a pair of dogs who were sitting just outside the gates to the park, just reaching down to pat their soft black heads – and wham! Just like that they were on to me, one with my hand in its mouth, the other grabbing on tight to the hem of my jacket. “Hang on a minute, you two,” I heard myself say, “this isn’t what you’re supposed to do. You’re Labradors, for goodness’ sake.” At which point, hearing myself speak, I woke up.

Of course everyone knows about dreams like this, about Jung and Freud, those dream counsellors with their unconscious-world this and their myths-and-meanings that. And sure, we all know about the biting-dog dream: that it’s about either sexual repression or confidence. Or fear of sex. Or too much, or not enough. Whatever. So I suppose it could be that the dream itself might be a little short story if I wanted. It’s starting the writing classes that got me thinking this way. You, whoever you are, are reading now because you like reading, you’re used to it – even something like this, a short story from a writing class – and you’re used to thinking of life in a fictional sort of way; you probably write short stories yourself. But for me, finding meanings in the day-to-day, using them to create a written piece of work … It’s weird and it’s exciting. Now I think back on so many things that have happened to me and find shapes in those things, patterns … Like how come I went through most of my adult life in and out of relationships when I know I’ve got my own ways of going about things, always have had, so why should I be surprised they didn’t work out? Of course it comes of being a professional athlete, my mother used to say, as well as having my own business and telling people all the time: You’ve got to do this, you’ve got to do that.

And here I am, still doing those things – giving the aerobics and weights lessons, signing up new clients for training, etc. etc. – but also taking writing classes, and everything changed for me because of that. And maybe it’s what the dream was telling me – reminding me of that connection between life and art. Who knows. All I can tell you is that when I started this particular exercise – the title we were given: “Something that really happened that has far-reaching consequences” – I just thought, first off: Hey, get the biting dogs in, Kitty. Start with that.

The class I go to isn’t strictly short story writing. It’s “Life Writing” with various approaches to prose. We, to quote the course leaflet, “draw from material that has occurred in the student’s life and from that fashion stories and non-fiction articles – ‘prose artworks’ – that both transform the original and stay true to its shape and turn of events”. Amazing, right? That a class could deliver that kind of result with a bunch of men and women in their thirties to sixties, taking two hours of night school per week to “hone their writing skills”? Well, that’s Reed Garner for you, that one man. He developed the course and teaches the whole thirty-two weeks’ worth of it, and he knows what he’s doing because he is an American short story writer who himself writes from life, creates those “prose artworks”, and though no one here has heard of him he’s quite a big name in the States, with stuff in the New Yorker and collections of short fiction and has won big prizes over there too – all this information I have at my fingertips, now, you see, and can write about with such authority and ease. I also know that he has taught at Princeton and Yale and is Visiting Professor of Short Fiction at St Hilda’s College, Oxford, which is where my mother used to go. So, hey. I guess I was bound to feel a connection. Because my mother was a big presence in my life, I must tell you, massive, and my dad, too, and I miss them both more than I can say.

Still, even with all these credentials running from him like water, he’s a teacher who doesn’t make a big deal of that. From the outset he said, “Guys, we’re all in this together. Just because you’re starter-writers and I’ve been doing it longer doesn’t make me your professor any more than it makes any of you a student. You’ll be teaching me easily as much, if not more, than I’ll ever be able to show you.” And then he did this thing with his hair – he has super-long hair that’s white as white because of being part Native American and he has to keep flipping it back to get it out of his way – flipping it back and then with one hand gathering it up and twisting it into a pretty little rough ponytail or bun, talking all the while. “So teach me,” he was saying. “I’ll be paying attention to you all.”

For my part, I couldn’t listen hard enough, pay attention close enough … “Reed Garner. Just say his name out loud, Kitty,” I used to murmur to myself as I was walking home, those first few classes. Not even thinking about going for a run or working out. Just going over ideas about fiction and prose and Reed Garner, saying his name. One day he cycled past me as I was in this kind of daydream and when I lunged out of my thoughts to shout “Hi!” he nearly fell off his bike, took a sort of tumble to avoid hitting me, but then went on his way.

Already that feels like a long time ago, when we sort of crashed into each other like that on the street … But I know it’s got nothing to do with my “gateway” and “Something that really happened that has far-reaching consequences”, so I’d better get on with all that now.

Well, I was running, as I do every morning, through the park, coming back around seven, getting to the front gates, and there up ahead I saw, seven o’clock in the morning, remember, a gang of kids, teenagers I thought at first but more like in their early twenties, and they were laughing at something, a shouting and jeering that sounded like a crowd – though I saw when I got closer that there were only four of them. The thing they were all looking down at was a dog, a pit bull terrier, with a black, flat expression in its eyes. Its ears were back, and its head down, its tail level, and it was pretty unhappy, twitching and twisting on a chain because those kids were tormenting it. One was bent over and jeering at the dog and poking him with a stick to make him mad and he was spinning around and snapping at it. Another was yanking on the chain. “Nah, Rocky!” one of the kids sneered at him, and tickled his balls when the chain was pulled back so tight I could see the little dog was nearly choking. “Yah, pussy!” the kid said, and made to kick him when his friend released his grip.

Now I may be a personal trainer and strong, but actually I’m quite small. And I may be super-fit, I am, but I wouldn’t describe myself as brawny. Still I hate to see a dog being taunted – any animal, but dogs especially. Perhaps that’s because I’d always had dogs as a kid and my parents, when they were still alive, used to take in strays and mutts, “orphan anything”, my mother used to say – I was an orphan myself, you see, and my mother and father took me in – and I’d always thought I’d have a dog one day, when I quit the personal training … Anyhow, when I saw those kids, well, young men really, they weren’t kids at all, when I saw them taunting that little dog so that he was snapping and growling and starting to look as if any minute he was going to slip his chain and make a lunge and then there’d be trouble … Well, I saw red.

Professor Garner – just joking: I mean, Reed – says we must never use clichés in a story. “Do anything to avoid ’em, kids,” he says, in his American way. Yet sometimes, like just then, it seems there is no way around them. Because I did … see red. We’d been reading Jane Eyre in class, as part of a study of “the intersection between Life Writing and Fiction”, and looking at how that novel by Charlotte Brontë seems for all the world to be just the story of a particular woman’s life, a study of Jane, and not the usual kind of fiction with a plot that has been figured out in advance to make it seem exciting. The red room in that book – it’s there towards the beginning when Jane is being punished by her terrible aunt – and the idea that it might surround a person, that colour, might make her see things in a particular way … well, that detail stayed with me. All that opening section, actually, because I related to it, maybe, with being an orphan too and my parents only adopting me when I was four so I can remember that other part of my life, not in detail, maybe, the orphanage or “home”, as people always called it, but I can remember my mother and father walking towards me that day they came to collect me, and my mother getting down on her knees in front of me and opening her arms and I ran towards her … And I can remember, too, exactly how I felt, being held in her arms that first time … So yes, the early section of Jane Eyre, it stayed with me, how it must have been for Jane to have that terrible aunt and not someone like my mother and what it must have been like, growing up so alone … And “seeing red”, well, altogether it seems a likely expression for me to use – cliché or not – when that book had been so clearly in my mind.

I saw red with what those kids were doing. So instead of walking on, I went straight up to those boys, young men, whatever, and said, “What on earth are you doing?”

Let me tell you, that was a moment. A moment, right then, of silence. Then one of the men said, “Fuck off, bitch,” and the one beside him, “Yeah. Fuck off,” and then someone else said, in a low and dangerous voice, “Get her, Rocky. Get her,” and the dog turned.

Now again, as I say, I’m not tall and what do I know? And I’m not brawny in any way and I’m not confrontational with strangers, but neither do I believe anyone is inherently mean, human or animal, boy or dog … I just don’t believe it. It’s like bodies. You can be overweight or your tone can be shot to hell or you’ve got no endurance, no core strength … but I can work with you on that. Take my classes and you’ll see, straight away, how together we can improve things. I’m saying all this as a kind of metaphor, I guess, as a way of showing that I wasn’t about to walk away from that situation, even though the boy who held the dog lengthened the chain and the dog lit out at me and someone said, “Get her, Rocky,” again, but then the boy with the chain pulled it back just in time, so that nothing happened, even though the little guy’s teeth were bared and his eyes like a shark because he was ready to get me all right, he’d been commanded.

“You’re being very cruel to that dog,” I said then. “How old are you all, anyway? Twenty? Thirty? You should know better. Here …” and at that point I got down on my knees, just like my mother got down on her knees that day at the orphanage, and the little dog looked at me, and his expression changed. His ears went up. He put his head to one side.

“Look at him,” I said to the boys, for now I could see that they were just boys, I’d kind of made that up about them being twenty or thirty, just to flatter them, because they wanted to be very, very tough. “Look,” I said again, from down there, though one of them was lashing some other chain he had, and another was muttering over and over in a dark low voice, “Fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck, fuck,” just like that, and another turned to spit.

“Look,” I said again, for the third time. And then I put out my balled fist and the dog stretched his head towards me. Then he stood up, took a step or two, his head still tilted to one side, while all the time I kept my fist in front of him, quite steady. Then he let out a little whimper and sat down again. He had a lovely face. His eyes, which had been black and scary-flat like a killer fish, were now full of thoughts and interest. He gave a little bark, like a puppy. He was really just a puppy. He put out his head towards my hand and smelled my hand all over and then he licked it. And I opened my hand then to let him sniff my palm and then, when he’d done that, too, I gave him a little scratch around his ears and fondled his muzzle.

“There,” I said to him, and sort of to the boys as well. “There, you see? Everything’s all right.”

The boys kind of shuffled, reassembled slightly. The one with the chain just let the chain hang.

“You see,” I said, “you think you’ve got a mean dog here, boys. But” – I wasn’t looking at them as I spoke. I was just looking at the dog – “he’s not mean at all.”

“He should be fucking mean,” said one of them, the one who had been swinging a length of chain attached to his jeans, though he wasn’t swinging it now. “He should fucking be.”

“But he’s not, Steve,” said the guy holding the actual dog chain. “Look at him. He’s a pussy. He’s a mummy’s dog.”

“My old mum wouldn’t be seen dead with a dog like that,” the third boy said. “She wouldn’t be seen dead.”

“His name’s not even Rocky,” I said then. “It’s Mr Rochester. Little Roc, for short, because look, he’s only a puppy …” By now the boys could see that the little dog was wriggling with pleasure, tail wagging, only wanting to play. Not the kind of dog they’d thought he was at all. “He’s named after a guy I’ve been reading about in this book about someone’s life,” I said. “That guy is a bit like this little dog of yours. He may seem all tough and mean but really …” And I gave Little Roc a lovely rub all over his haunches and down his back. “Really,” I said, “this little guy wants – like all of us want – like you boys yourself want” – and by now I had the puppy snuggled up right by me, his eyes closed with pleasure – “someone to give him attention and to love him and to love them back.”