Полная версия:

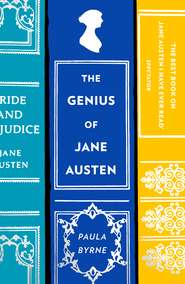

The Genius of Jane Austen: Her Love of Theatre and Why She Is a Hit in Hollywood

In order to be available for the proof-reading of Sense and Sensibility, she went to London in April 1811, staying with Henry and Eliza at their new home in Sloane Street. Shortly after her arrival she expressed a desire to see Shakespeare’s King John at Covent Garden. In the meantime, she sacrificed a trip to the Lyceum, nursing a cold at home, in the hope of recovering for the Saturday excursion to Covent Garden:

To night I might have been at the Play, Henry had kindly planned our going together to the Lyceum, but I have a cold which I should not like to make worse before Saturday … [Later on Saturday] Our first object to day was Henrietta St to consult with Henry, in consequence of a very unlucky change of the Play for this very night – Hamlet instead of King John – & we are to go on Monday to Macbeth, instead, but it is a disappointment to us both. (Letters, pp. 180–81)

Her preference for King John over Hamlet may seem curious by modern standards, but can be explained by one of the intrinsic features of Georgian theatre: the orientation of the play towards the star actor in the lead role. Her disappointment in the ‘unlucky change’ of programme from ‘Hamlet instead of King John’ is accounted for in her next letter to Cassandra:

I have no chance of seeing Mrs Siddons. – She did act on Monday, but as Henry was told by the Boxkeeper that he did not think she would, the places, & all thought of it, were given up. I should particularly have liked seeing her in Constance, & could swear at her with little effort for disappointing me. (Letters, p. 184)

It was not so much King John that Austen wanted to see as Siddons in one of her most celebrated roles: Queen Constance, the quintessential portrait of a tragic mother. In the words of her biographer and friend, Thomas Campbell, Siddons was ‘the imbodied image of maternal love and intrepidity; of wronged and righteous feeling; of proud grief and majestic desolation’.6 Siddons’s own remarks on this ‘life-exhausting’ role, and the ‘mental and physical’ difficulties arising from the requirements of playing Constance provide a striking testimony to her all-consuming passion and commitment to the part. Siddons records:

Whenever I was called upon to personate the character of Constance, I never, from the beginning of the play to the end of my part in it, once suffered my dressing-room door to be closed, in order that my attention might be constantly fixed on those distressing events which, by this means, I could plainly hear going on upon the stage, the terrible effects of which progress were to be represented by me.7

Though her part was brief – she appeared in just two acts – Siddons’s impassioned interpretation was acclaimed. Constance’s famously eloquent speeches and frenzied lamentations for her dead boy were newly rendered by Siddons, for she didn’t ‘rant’ and produce the effects of noisy grief but was stunningly understated, showing grief ‘tempered and broken’, as Leigh Hunt put it.8 While admitting that King John was ‘not written with the utmost power of Shakespeare’, Hunt nevertheless viewed the play as a brilliant vehicle for Siddons’s consummate tragic powers.9 Her biographer, Thomas Campbell, also claimed that Siddons’s single-handedly resuscitated the play, winning over the public to ‘feel the tragedy worth seeing for the sake of Constance alone’.10

Jane Austen certainly felt that ‘Constance’ was worth the price of a ticket. Though Henry Austen was misinformed by the box-keeper and Siddons had indeed appeared in Macbeth on Monday (22 April), Jane was less sorry to have missed her in Lady Macbeth than in Constance, which may imply that she had previously seen her in Macbeth. Sarah Siddons acted Lady Macbeth eight times and Constance five times that 1811–12 season, before retiring from the London stage, so perhaps Jane finally got her wish.11

On Saturday (20 April) the party went instead to the Lyceum Theatre in the Strand, where the Drury Lane company had taken their patent after the fire in 1809.12 They saw a revival of Isaac Bickerstaffe’s The Hypocrite.

We did go to the play after all on Saturday, we went to the Lyceum, & saw the Hypocrite, an old play taken from Moliere’s Tartuffe, & were well entertained. Dowton & Mathews were the good actors. Mrs Edwin was the Heroine – & her performance is just what it used to be. (Letters, p. 184)

In The Hypocrite, the roles of Maw-Worm, an ignorant zealot, and the religious and moral hypocrite Dr Cantwell were acted by the renowned comic actors Charles Mathews (1776–1835), and William Dowton (1764–1851), singled out by Jane Austen for praise. Dowton was famous for his roles as Dr Cantwell, Sir Oliver Premium and Sir Anthony Absolute.13 Leigh Hunt described his performance in the Hypocrite as ‘one of the few perfect pieces of acting on the stage’.14

The great comic actor Charles Mathews was also a favourite of Hunt’s: ‘an actor of whom it is difficult to say whether his characters belong most to him or he to his characters’.15 Mathews was so tall and thin that he was nicknamed ‘Stick’; when his manager Tate Wilkinson first saw him he called him a ‘Maypole’, told him he was too tall for low comedy and quipped that ‘one hiss would blow him off the stage’.16

Mathews himself described the success of The Hypocrite at the Lyceum, and recorded his experiment in adding an extra fanatical speech for Maw-Worm, thus breaking the rule of his ‘immortal instructor, who says “Let your clowns say no more than is set down for them”.’ His experiment worked, and the reviews were favourable: ‘It was an admirable representation of “Praise God Barebones”, an exact portraiture of one of those ignorant enthusiasts who lose sight of all good while they are vainly hunting after an ideal perfectibility.’17 Jane Austen dearly loved a fool – in Pride and Prejudice she portrayed her own obsequious hypocrite and ignorant enthusiast, in Mr Collins and Mary Bennet.

Elizabeth Edwin (1771–1854), the wife of the actor John Edwin, performed the part of Charlotte, the archetypal witty heroine, for which she was famous.18 The Austen sisters were clearly familiar with Mrs Edwin’s acting style. She had played at Bath for many years, including the time that the Austens lived there, and she was also a favourite of the Southampton theatre, where the sisters may have seen her perform.19

Elizabeth Edwin was one of many actors from the provinces who had begun her career as a child actor in a company of strolling players. She was the leading actress at Wargrave at the Earl of Barrymore’s private theatricals.20 She was often (unfairly) compared to the great Dora Jordan, whose equal she never was, though they played the same comic roles. Jane Austen’s ambiguous comment about Edwin suggests that she did not rate her as highly as Dowton and Mathews, whom she regarded as the ‘good actors’ in The Hypocrite. Oxberry’s 1826 memoir observed that although Edwin was ‘an accomplished artist … she has little, if any, genius – and is a decided mannerist’.21 She was an ‘artificial’ actress who betrayed the fact that she was performing:

Though we admired what she did, she never carried us with her. We knew that we were at a display of art, and never felt for a moment the illusion of its being a natural scene.22

The preoccupation with the play as a vehicle for the star actor, popularly called ‘the possession of parts’, went hand-in-hand with the theatre’s proclivity towards an established repertory.23 It was common to see the same actor in a favourite role year in, year out. Dora Jordan’s Rosalind and Little Pickle, both of them ‘breeches’ roles, were performed successfully throughout her long career. Siddons’s Lady Macbeth and Constance were staples of her repertory throughout her career, and, even after her retirement, they were the subject of comparison with other performances. The tradition of an actor’s interpretation of a classic role, which still survives today, was an integral part of an individual play’s appeal. Critics and the public would revel in the particularities of individual performances, and they would eagerly anticipate a new performance of a favourite role, though innovations by actors were by no means a guarantee of audience approbation.

In the early autumn of 1813, Jane Austen set out for Godmersham, stopping on the way in London, where she stayed with her brother Henry in his quarters over his bank at Henrietta Street, Covent Garden. On the night of 14 September, the party went by coach to the Lyceum Theatre, where they had a private box on the stage. As soon as the rebuilt Drury Lane had opened its doors to the public, the Lyceum had no choice but to revert to musical drama. The Austens saw three musical pieces. The first was The Boarding House: or Five Hours at Brighton; the second, a musical farce called The Beehive; and the last Don Juan: or The Libertine Destroyed, a pantomime based on Thomas Shadwell’s The Libertine. Once again, Jane Austen’s reflections on the plays were shared with Cassandra:

I talked to Henry at the Play last night. We were in a private Box – Mr Spencer’s – Which made it much more pleasant. The Box is directly on the Stage. One is infinitely less fatigued than in the common way … Fanny & the two little girls are gone to take Places for tonight at Covent Garden; Clandestine Marriage & Midas. The latter will be a fine show for L. & M. – They revelled last night in ‘Don Juan’, whom we left in Hell at half-past eleven … We had Scaremouch & a Ghost – and were delighted; I speak of them; my delight was very tranquil, & the rest of us were sober-minded. Don Juan was the last of 3 musical things; – Five hours at Brighton, in 3 acts – of which one was over before we arrived, none the worse – & The Beehive, rather less flat & trumpery. (Letters, pp. 218–19)

The Beehive was an adaptation of Kotzebue’s comedy Das Posthaus in Treuenbrietzen. Two lovers who have never met, but who are betrothed to one another, fall in love under assumed names. The young man discovers the ruse first and introduces his friend as himself; meanwhile the heroine, Miss Fairfax, in retaliation pretends to fall in love with the best friend. In the light of Emma, the conjunction of name and plot-twist is striking.

Austen clearly preferred the Kotzebue comedy to Five Hours at Brighton, a low comedy set in a seaside boarding house. Her ‘delight’ in Don Juan is properly amended to ‘tranquil delight’ for the sake of the upright Cassandra. Byron had also seen the pantomime, in which the famous Grimaldi played Scaramouch, to which he alludes in his first stanza of Don Juan:

We all have seen him, in the pantomime,

Sent to the devil somewhat ere his time.24

Scaramouch was one of Grimaldi’s oldest and most frequently revived parts.

In her letter to Cassandra, Jane gives her usual precise details of the theatre visit, even down to the private box, ‘directly on the stage’. Again, the Austens showed their support for the minor theatres, and Henry is arranging trips to the Lyceum. Perhaps he had an arrangement with his friend Mr Spencer to share each other’s boxes at the minor theatres. Being seated in a box certainly meant that Jane could indulge in intimate discussion with Henry – as Elizabeth Bennet does with Mrs Gardiner in Pride and Prejudice.25

As planned, the very next night the party went to Covent Garden Theatre, where they had ‘very good places in the Box next the stage box – front and second row; the three old ones behind of course’.26 They sat in Covent Garden’s new theatre boxes, presumably in full consciousness that, at the opening of the new theatre, riots had been occasioned by the extra number of private and dress boxes.27 The parson and poet George Crabbe and his wife were in London and Jane Austen joked about seeing the versifying vicar at the playhouse, particularly as the ‘boxes were fitted up with crimson velvet’ (Letters, pp. 220–21). The remark skilfully combines an allusion to Crabbe’s Gentleman Farmer, ‘In full festoons the crimson curtains fell’,28 with detailed observation of the lavish fittings of the new Covent Garden Theatre, recently reopened after the fire of 1809. Edward Brayley’s account of the grand new playhouse also singled out the ‘crimson-covered seats’,29 and described the grand staircase leading to the boxes, and the ante-room with its yellow-marble statue of Shakespeare.

The Austens saw The Clandestine Marriage by David Garrick and George Colman the Elder, and Midas: an English Burletta by Kane O’Hara, a parody of the Italian comic opera.30 One of the attractions was to see Mr Terry, who had recently taken over the role of Lord Ogleby in The Clandestine Marriage.

The new Mr Terry was Ld Ogleby, & Henry thinks he may do; but there was no acting more than moderate; & I was as much amused by the remembrances connected with Midas as with any part of it. The girls were very much delighted but still prefer Don Juan – & I must say I have seen nobody on the stage who has been a more interesting Character than that compound of Cruelty & Lust. (Letters, p. 221)

Daniel Terry (1780–1829) had made his debut at Covent Garden on 8 September, just a few days before Jane Austen saw him.31 Sir Walter Scott was a great friend and admirer of Terry (who adapted several of the Waverley novels for the stage),32 and claimed that he was an excellent actor who could act everything except lovers, fine gentlemen and operatic heroes. Scott observed that ‘his old men in comedy particularly are the finest I ever saw’.33 Henry Austen showed a little more tolerance than his sister in allowing Mr Terry teething troubles in the role of one of the most celebrated old men of eighteenth-century comedy.

Henry Austen’s faith in Terry’s capacity to grow into a beloved role reflects the performer-oriented tendency of the age. But Jane’s powerful and striking description of Don Juan is a far less typical response. Here a more discerning and discriminating voice prevails. Rather than the performer being the main focus of interest, she is responding to the perverse appeal of the character beneath the actor. The famous blackguard was still obviously on her mind, belying her earlier insistence upon ‘tranquil delight’ and ‘sober-mindedness’.

Jane Austen’s reference to Midas confirms that she had seen this entertainment at an earlier date. Garrick and Colman’s brilliant comedy The Clandestine Marriage had also been known to her for a long time. The title appears as a phrase in one of her early works, Love and Freindship, and, as will be seen, the play was a source for a key scene in Mansfield Park.

Austen was disappointed with her latest theatrical ventures, though had she stayed longer in London she might have been disposed to see Elliston in a new play, First Impressions, later that month.34 When she wrote to her brother Frank, she complained of the falling standards of the theatres:

Of our three evenings in Town one was spent at the Lyceum & another at Covent Garden; – the Clandestine Marriage was the most respectable of the performances, the rest were Sing-song & trumpery, but did very well for Lizzy & Marianne, who were indeed delighted; but I wanted better acting. – There was no Actor worth naming. – I beleive the Theatres are thought at a low ebb at present. (Letters, p. 230)

Austen’s heart-felt wish for ‘better acting’, or, in Edmund Bertram’s words, ‘real hardened acting’, was soon to be realised.

Drury Lane had indeed reached its lowest ebb for some years when it was rescued by the success of a new actor, Edmund Kean (1787–1833), who made his electrifying debut as Shylock in January 1814. The story of his stage debut has become one of the most enduring tales of the theatre. The reconstructed Drury Lane Theatre, rebuilt after it was destroyed by fire in 1809, was facing financial ruin, greatly exacerbated by the ruinous management of R. B. Sheridan, when a strolling player from the provinces, Edmund Kean, was asked to play Shylock.35 Kean, in his innovative black wig, duly appeared before a meagre audience, mesmerising them by his stage entrance. At the end of the famous speech in the third act, the audience roared its applause. ‘How the devil so few of them kicked up such a row’, said Oxberry, ‘was something marvelous.’36 Kean’s mesmerising appearance on the stage was given the seal of approval when Hazlitt, who after seeing him on the first night, raved: ‘For voice, eye, action, and expression, no actor has come out for many years at all equal to him.’37

The news of Kean’s conquest of the stage reached Jane Austen, and in early March 1814, while she was staying with Henry during the negotiations for the publication of Mansfield Park, she made plans to see the latest acting sensation:

Places are secured at Drury Lane for Saturday, but so great is the rage for seeing Keen [sic] that only a third & fourth row could be got. As it is in a front box however, I hope we shall do pretty well. – Shylock. – A good play for Fanny. She cannot be much affected I think. (Letters, p. 256)

The relatively short part of Shylock is thus considered to be a suitably gentle introduction to Kean’s powerful acting for the young girl. But Austen’s own excitement is barely contained in her description of the theatre party: ‘We hear that Mr Keen [sic] is more admired than ever. The two vacant places of our two rows, are likely to be filled by Mr Tilson & his brother Gen. Chownes.’ Then, almost as if she has betrayed too much pleasure in the absence of her sister, she writes: ‘There are no good places to be got in Drury Lane for the next fortnight, but Henry means to secure some for Saturday fortnight when You are reckoned upon’ (Letters, p. 256).

Another visit to see Kean was intended, and Henry’s acquaintance with the theatre world again emphasised. The party went to Drury Lane on the evening of 5 March, attending the eighth performance of The Merchant of Venice. Austen’s initial response to the latest acting phenomenon was calm and rational: ‘We were quite satisfied with Kean. I cannot imagine better acting, but the part was too short, & excepting him & Miss Smith, & she did not quite answer my expectations, the parts were ill filled & the Play heavy’ (Letters, p. 257). Hazlitt, too, frequently complained that one of the problems of the star system was filling up the smaller parts. In his review of The Merchant of Venice, he was only grudgingly respectful of the minor roles.

Kean was still very much on Austen’s mind, for in the same letter, in the midst of a sentence about Henry Crawford and Mansfield Park, she unexpectedly reverted to the subject of him with greater enthusiasm: ‘I shall like to see Kean again excessively, & to see him with You too; – it appeared to me as if there was no fault in him anywhere; & in his scene with Tubal there was exquisite acting’ (Letters, p. 258).

Jane Austen was conscious of the dramatic demands of Shylock’s scene, which required the actor to scale, alternately, between grief and savage glee. Her singling out of this particular scene was no doubt influenced by the reports of the opening night, where the audience had been powerless to restrain their applause. Kean’s biographer noted the subtle intricacies of the scene in the third act ending with the dialogue between Shylock and Tubal:

Shylock’s anguish at his daughter’s flight, his wrath at the two Christians who had made sport of his suffering, his hatred of Christianity generally, and of Antonio in particular, and his alternations of rage, grief and ecstasy as Tubal enumerated the losses incurred in the search of Jessica – her extravagances, and then the ill-luck that had fallen on Antonio; in all this there was such originality, such terrible force, such assurance of a new and mighty master, that the house burst forth into a very whirlwind of approbation.38

For many critics, the greatest quality of Kean’s as Shylock was his ability to change emotional gear at high speed, to scale the highest points and the lowest. Thus Hazlitt:

In giving effect to the conflict of passions arising out of the contrasts of situation, in varied vehemence of declamation, in keenness of sarcasm, in the rapidity of his transitions from one tone and feeling to another, in propriety and novelty of action, presenting a succession of striking pictures, and giving perpetually fresh shocks of delight and surprise, it would be difficult to single out a competitor.39

Kean’s acting style was hereafter characterised as impulsive, electric and fracturing. ‘To see him act’, Coleridge observed famously in his Table Talk, ‘is like reading Shakespeare by flashes of lightning.’40

In contrast to her reaction to Kean, Jane Austen was disappointed with the performance of her old favourite Elliston. The programme that night included him in an oriental ‘melodramatic spectacle’ called Illusion; or The Trances of Nourjahad. The Austen party left before the end:

We were too much tired to stay for the whole of Illusion (Nourjahad) which has 3 acts; – there is a great deal of finery & dancing in it, but I think little merit. Elliston was Nourjahad, but it is a solemn sort of part, not at all calculated for his powers. There was nothing of the best Elliston about him. I might not have known him, but for his voice. (Letters, pp. 257–58)

Henry Crabb Robinson also saw Elliston as Nourjahad and wrote in his diary that ‘his untragic face can express no strong emotions’. Robinson admired Elliston as a ‘fine bustling comedian’, but thought that he was a ‘wretched Tragedian’.41 Austen’s observation that Elliston’s brilliance lay especially in his comic powers was a view shared by his critics and admirers. Charles Lamb thought so too, but was afraid to say so when Elliston recounted how Drury Lane was abusing him. Lamb recorded: ‘He complained of this: “Have you heard … how they treat me? they put me in comedy.” Thought I – “where could they have put you better?” Then, after a pause – “Where I formerly played Romeo, I now play Mercutio.”’42

Austen’s ‘best Elliston’ was altered from his glory days at Bath and his early promise at Drury Lane as a result of physical deterioration brought on by hard drinking. His acting powers had steadily declined. From managing various minor and provincial theatres, he finally became the lessee and manager of Drury Lane from 1819 until 1826, when he retired, bankrupt through addiction to drinking and gambling.

Elliston’s acting talent suffered when he threw his energies into his multifarious business ventures. The London Magazine and Theatrical Inquisitor observed that in later years he had fallen into ‘a coarse buffoonery of manner’ and Leigh Hunt oberved that he had ‘degraded an unequivocal and powerful talent for comedy into coarseness and vulgar confidence’.43

Three days after seeing Kean and Elliston at Drury Lane, Jane Austen went to the rival house Covent Garden to see Charles Coffey’s farce, The Devil to Pay. ‘I expect to be very much amused’, she wrote in anticipation (Letters, p. 260). Dora Jordan played Nell, one of her most famous comic roles. The party were to see Thomas Arne’s opera Artaxerxes with Catherine Stephens (1794–1882), the celebrated British soprano who later became Countess of Essex. She was, however, less excited by the opera than the farce: ‘Excepting Miss Stephens, I dare say Artaxerxes will be very tiresome’ (Letters, p. 260). Catherine Stephens acted Mandane in Artaxerxes, a role in which Hazlitt thought she was superb, claiming that he could hear her sing ‘forever’: ‘There was a new sound in the air, like the voice of Spring; it was as if Music had become young again, and was resolved to try the power of her softest, simplest, sweetest notes.’44 Austen’s response was just as she expected: ‘I was very tired of Artaxerxes, highly amused with the Farce, & in an inferior way with the Pantomime that followed’ (Letters, p. 260). However, she was unimpressed with Catherine Stephens and grumbled at the plan for a second excursion to see her the following night: ‘I have had enough for the present’ (Letters, p. 260).