Полная версия:

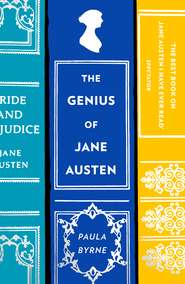

The Genius of Jane Austen: Her Love of Theatre and Why She Is a Hit in Hollywood

Henry Austen tells us in his ‘Biographical Notice’, published in the first edition of Northanger Abbey and Persuasion, that his sister Jane was acquainted with all the best authors at a very early age (NA, p. 7). The literary tastes of Catherine Morland have often been read as a parody of the author’s own literary preferences.43 Catherine likes to read ‘poetry and plays, and things of that sort’, and while ‘in training for a heroine’, she reads ‘all such works as heroines must read to supply their memories with those quotations which are so serviceable and so soothing in the vicissitudes of their eventful lives’ (NA, p. 15): dramatic works, those of Shakespeare especially, are prominent among these. Twelfth Night, Othello and Measure for Measure are singled out. Catherine duly reads Shakespeare, alongside Pope, Gray and Thompson, not so much for pleasure and entertainment, as for gaining ‘a great store of information’ (NA, p. 16).

In Sense and Sensibility, Willoughby and the Dashwoods are to be found reading Hamlet aloud together. In Mansfield Park, the consummate actor Henry Crawford gives a rendering of Henry VIII that is described by Fanny Price, a lover of Shakespeare, as ‘truly dramatic’ (MP, p. 337). Henry memorably remarks that Shakespeare is ‘part of an Englishman’s constitution. His thoughts and beauties are so spread abroad that one touches them every where’. This sentiment is reiterated by Edmund when he notes that ‘we all talk Shakespeare, use his similes, and describe with his descriptions’ (MP, p. 338). Though Emma Woodhouse is not a great reader, she is found quoting passages on romantic love from Romeo and Juliet and A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Henry and Edmund agree on very little. It is therefore a fair assumption that, when they do concur, they are voicing the opinion of their author. Their consciousness of how Shakespeare is assimilated into our very fibre, so that ‘one is intimate with him by instinct’, reaches to the essence of Jane Austen’s own relationship with him. She would have read the plays when a young woman, but she would also have absorbed famous lines and characters by osmosis, such was Shakespeare’s pervasiveness in the culture of the age. She quotes Shakespeare from memory, as can be judged by the way that she often misquotes him. Her surviving letters refer far more frequently to contemporary plays than Shakespearean ones, but Shakespeare’s influence on the drama of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century was so thoroughgoing – for instance through the tradition of the ‘witty couple’, reaching back to Love’s Labour’s Lost and Much Ado About Nothing – that her indirect debt to his vision can be taken for granted.

In her earliest works, however, Jane Austen showed a certain irreverence for the national dramatist. Shakespeare’s history plays are used to great satirical effect in The History of England, a lampoon of Oliver Goldsmith’s abridged History of England. Austen mercilessly parodied Goldsmith’s arbitrary and indiscriminate merging of fact and fiction, in particular his reliance on Shakespeare’s history plays for supposedly authentic historical fact. Austen, by contrast, is being satirical when she makes a point of referring her readers to Shakespeare’s English history plays for ‘factual’ information about the lives of its monarchs.44 Just as solemnly, she refers her readers to other popular historical plays, such as Nicholas Rowe’s Jane Shore and Sheridan’s The Critic (MW, pp. 140, 147). The tongue-in-cheek reference to Sheridan compounds the irony, as The Critic is itself a burlesque of historical tragedy that firmly eschews any intention of authenticity.

From such allusions in the juvenilia it is clear that Jane Austen was familiar with a wide range of plays, although these are probably only a fraction of the numerous plays that would have been read over as possible choices for the private theatricals, read aloud for family entertainment, or read for private enjoyment. While it is impossible to calculate the number of plays that she read as a young girl, since there is no extant record of Mr Austen’s ample library, the range of her explicit literary allusions gives us some idea of her extensive reading – references to over forty plays have been noted.45

Jane Austen owned a set of William Hayley’s Poems and Plays. Volumes one to five are inscribed ‘Jane Austen 1791’; volume six has a fuller inscription ‘Jane Austen, Steventon Sunday April the 3d. 1791’.46 Hayley was well known as the ‘friend and biographer’ of William Cowper, Austen’s favourite poet, though he fancied himself as a successful playwright. The most well-thumbed volume in Austen’s collection of Hayley was the one containing his plays. It contained five dramas in all: two tragedies, Marcella and Lord Russel, and three comedies in verse, The Happy Prescription: or the Lady Relieved from her Lovers; The Two Connoisseurs; and The Mausoleum.47

Like the Sheridan plays which the Austens adored, Hayley’s comedies depict the folly of vanity and affectation in polite society. By far the best of them is The Mausoleum, which dramatises excessive sensibility and ‘false refinement’ in the characters of a beautiful young widow, Sophia Sentiment, and a pompous versifier, Mr Rumble, a caricature of Dr Johnson. Lady Sophia Sentiment erects a mausoleum to house her husband’s ashes and employs versifiers to compose tributes for the inscription on the monument. The comedy explores the self-destructive effects of sensibility on the mind of a lovely young widow, who refuses to overcome her grief because of a distorted conception of refined sentiment. The tell-tale sign of misplaced sensibility is Lady Sophia’s obsession with black:

If cards should be call’d for to-night,

Place the new japann’d tables alone in my sight;

For the pool of Quadrille set the black-bugle dish,

And remember you bring us the ebony fish.48

But this sentiment is amusingly undercut by its correlation to hypocrisy and false delicacy:

Her crisis is coming, without much delay;

There might have been doubts had she fix’d upon grey:

But a vow to wear black all the rest of her life

Is a strong inclination she’ll soon be a wife.49

This comedy is of particular interest as the main character has the name that was adopted in a satirical letter to James Austen in his capacity as editor of The Loiterer. The letter complains of the periodical’s lack of feminine interest:

Sir, I write this to inform you that you are very much out of my good graces, and that, if you do not mend your manners, I shall soon drop your acquaintance. You must know, Sir, that I am a great reader, and not to mention some hundred volumes of Novels and Plays, have in the two last summers, actually got through all the entertaining papers of our most celebrated periodical writers.50

The correspondent goes on to complain of the journal’s lack of sentimental interest and offers recommendations to improve its style:

Let the lover be killed in a duel, or lost at sea, or you make him shoot himself, just as you please; and as for his mistress, she will of course go mad; or if you will, you may kill the lady, and let the lover run mad; only remember, whatever you do, that your hero and heroine must possess a great deal of feeling, and have very pretty names.51

The letter ends by stating that if the author’s wishes are not complied with ‘may your work be condemned to the pastry-cooke’s shop, and may you always continue a bachelor, and be plagued with a maiden sister to keep house for you’. It is signed Sophia Sentiment.

It is highly probable that Jane Austen wrote this burlesque letter to her brother. It is very close in spirit to her juvenilia of the same period. Love and Freindship also has a sentimental heroine named Sophia. It seems plausible that The Mausoleum was among the comedies considered for performance by the Austens when they were looking at material for home theatricals in 1788. This may have been the time that Jane first became acquainted with the name Sophia Sentiment. If Austen was indeed Sophia Sentiment, by her own admission, she was a great reader of some hundred volumes of novels and plays.

Austen also owned a copy of Arnaud Berquin’s L’ami des enfans (1782–83) and the companion series L’ami de l’adolescence (1784–85). Berquin’s little stories, dialogues and dramas were much used in English schools for young ladies towards the end of the eighteenth century, being read in the original for the language or in translation for the moral. Berquin states in his preface to L’ami des enfans that his ‘little dramas’ are designed to bring children of the opposite sex together ‘in order to produce that union and intimacy which we are so pleased to see subsist between brothers and sisters’.52 The whole of the family is encouraged to partake in the plays to promote family values:

Each volume of this work will contain little dramas, in which children are the principal characters, in order that they may learn to acquire a free unembarrassed countenance, a gracefulness of attitude and deportment, and an easy manner of delivering themselves before company. Besides, the performance of these dramas will be a domestic recreation and amusement.

Berquin’s short plays and dramatic dialogues were intended to instruct parents and children on manners and morals, on how to conduct themselves in domestic life, how to behave to one another, to the servants, and to the poor, and how to cope with everyday problems in the home. Some were directed towards young women, warning against finery and vanity. Fashionable Education, as its name suggests, depicts a young woman (Leonora) who has been given a fashionable town education, ‘those charming sciences called drawing, music, dancing’, but has also learned to be selfish, vain and affected.53 The blind affection of Leonora’s aunt has compounded her ruin. The moral of this play is that accomplishments should embellish a useful education and knowledge, not act as a substitute for them. A similar play, Vanity Punished, teaches the evils of coquetry, vanity, selfishness and spoilt behaviour.

Intriguingly, one of the playlets in the collection carries the same plot-line as Austen’s Emma. In Cecilia and Marian, a young, wealthy girl befriends a poor labourer’s daughter and ‘tastes the happiness of doing good’ when she feeds her new playmate plum cake and currant jelly:

Cecilia had now tasted the happiness of doing good. She walked a little longer in the garden, thinking how happy she had made Marian, how grateful Marian had shewed herself, and how her little sister would be pleased to taste currant jelly. What will it be, said she, when I give her some ribbands and a necklace! Mama gave me some the other day that were pretty enough; but I am tired of them now. Then I’ll look in my drawers for some old things to give her. We are just of a size, and my slips would fit her charmingly. Oh! how I long to see her well drest.54

Cecilia continues to enjoy her patronage until she is roundly scolded by her mother for her harmful and irresponsible conduct. By indulging and spoiling her favourite, Cecilia has made her friend dissatisfied with her previous life:

MOTHER: But how comes it, then, that you cannot eat dry bread, nor walk barefoot as she does?

CECILIA: The thing is, perhaps, that I am not used to it.

MOTHER: Why, then, if she uses herself, like you, to eat sweet things, and to wear shoes and stockings, and afterwards if the brown bread should go against her, and she should not be able to walk barefoot, do you think that you would have done her any service?55

Cecilia is an enemy to her own happiness and that of her ‘low’ friend Marian. She is only saved by the intervention and guidance of her judicious mother. In L’ami des enfans, mothers are often shown instructing, advising and educating their daughters: the plays were aimed at parents as well as children. In Emma, the variant on Berquin’s plot-line is a similarly meddlesome, though well-meaning, young woman who painfully lacks a mother figure.

Like Berquin, Austen wrote her own short plays and stories for domestic entertainment.56 But, rather than teaching morals and manners, Austen’s playlets parody the moral didacticism of Berquin’s thinly disguised conduct books. There are three attempts at playwriting in Austen’s juvenilia. The first two, ‘The Visit’ and ‘The Mystery’ in Volume the First, were written between 1787 and 1790.57 The third, ‘The First Act of a Comedy’, is one of the ‘Scraps’ in Volume the Second and dates from around 1793.

As mentioned earlier, ‘The Visit’ was probably written in 1789, the same time as the Steventon performance of Townley’s High Life Below Stairs. The play depicts a dinner engagement at Lord Fitzgerald’s house with a party of young people. Dining room etiquette is satirised in this piece, as the characters pompously make formal introductions to one another, then promptly discover that there are not sufficient chairs for them all to be seated:

MISS FITZGERALD: Bless me! there ought to be 8 Chairs & there are but 6. However, if your Ladyship will but take Sir Arthur in your Lap, & Sophy my Brother in hers, I beleive we shall do pretty well.

SOPHY: I beg you will make no apologies. Your Brother is very light. (MW, p. 52)

The conversation between the guests is almost wholly preoccupied with the main fare of ‘fried Cowheel and Onion’, ‘Tripe’ and ‘Liver and Crow.’ The vulgarity of the food on offer is contrasted with the polite formality of the guests:

CLOE: I shall trouble Mr Stanley for a Little of the fried Cowheel & Onion.

STANLEY: Oh Madam, there is a secret pleasure in helping so amiable a Lady –.

LADY HAMPTON: I assure you my Lord, Sir Arthur never touches wine; but Sophy will toss off a bumper I am sure to oblige your Lordship. (MW, p. 53)

Banal remarks about food and wine lead irrationally to unexpected marriage proposals for the three young women at the table, who eagerly accept without a second’s hesitation.

On the surface, Austen’s parody of a dull social visit derives its comic impact from the farcical touches and the juxtapositions of polite formalities with vulgar expressions. The young heroine, Sophy, like so many of Austen’s early creations, is portrayed as a drunk who can ‘toss off a bumper’ at will. Above all, there is an irrepressible delight in the sheer absurdity of table manners. The Austens performing this play would, of course, be expected to maintain their composure when solemnly requesting ‘fried Cowheel & Onion’ and ‘Liver & Crow’ (MW, p. 53).

Austen’s playlet, deriding the absurdity and pomposity of table etiquette, provides a mocking contrast to the morally earnest tone of Berquin’s instructive playlets. His Little Fiddler also dramatises a social visit, where the exceptionally rude behaviour of a young man to his sister (Sophia) and to her visitors, the Misses Richmonds, leads to expulsion from the family circle. Charles, the ill-mannered brother and deceitful, greedy son, is eventually turned out of his father’s house for his treachery and lies, and for his cruel treatment of a poor fiddler. In Berquin’s play, the virtues of polite conduct are piously upheld:

SOPHIA: Ah! how do you do, my dear friends! [They salute each other, and curtsy to Godfrey, who bows to them.]

CHARLOTTE: It seems an age since I saw you last.

AMELIA: Indeed it is a long time.

SOPHIA: I believe it is more than three weeks. [Godfrey draws out the table, and gives them chairs.]

CHARLOTTE: Do not give yourself so much trouble, Master Godfrey.

GODFREY: Indeed, I think it no trouble.

SOPHIA: Oh, I am very sure Godfrey does it with pleasure, [gives him her hand.] I wish my brother had a little of his complaisance.

The stilted artificiality of such social visits is precisely the target of Jane Austen’s satire in ‘The Visit’. She seemed to have little time for plays which dictated appropriate formal conduct, preferring comedies which satirised social behaviour. Jane Austen mocks Berquin and simultaneously begins to explore the incongruities and absurdities of restrictive social mores.58

As noted, a more direct source for ‘The Visit’ was Townley’s High Life Below Stairs. Austen’s quotation ‘The more free, the more welcome’ (MW, p. 50) nods to Townley’s farce, where fashionably bad table manners are cultivated by the servants in an attempt to ape their masters. Berquin wrote didactic plays instructing the correct ways to treat servants, both honest and dishonest. Townley’s hilarious farce of social disruption dramatises a lord who disguises himself as a servant to spy on his lazy servants, so that he can punish them appropriately for taking over his house.59

Austen dedicated ‘The Visit’ to her brother James. Intriguingly, in her dedication, she recalled two other Steventon plays. These ‘celebrated comedies’ were probably written by James, since Jane describes her own ‘drama’ as ‘inferior’ to his:

Sir, The Following Drama, which I humbly recommend to your Protection & Patronage, tho’ inferior to those celebrated comedies called ‘The School for Jealousy’ & ‘The travelled Man’, will I hope afford some amusement to so respectable a Curate as yourself; which was the end in veiw [sic] when it was first composed by your Humble Servant the Author. (MW, p. 49)

James had recently returned from his travels abroad, so ‘the travelled Man’ may have been based on his adventures. The two play-titles echo the form of several favourites in the eighteenth-century dramatic repertoire: Goldsmith’s The Good-Natur’d Man (1768), Arthur Murphy’s The School For Guardians (1769), and Richard Cumberland’s The Choleric Man (1774), Sheridan’s The School for Scandal (1777), and Hannah Cowley’s School for Elegance (1780).

‘The Mystery’ was probably performed as an afterpiece to the Steventon 1788 ‘Private Theatrical Exhibition’.60 Austen dedicated it to her father, and it may well have been a mocking tribute to one of his favourite plays. It has been suggested that the whispering scenes in this playlet were based on a similar scene in Sheridan’s The Critic.61 Jane Austen’s parody is, however, closer to Buckingham’s burlesque, The Rehearsal, which Sheridan was self-consciously reworking in The Critic.62 It is most likely that Austen was parodying the whispering scene in The Rehearsal, where Bayes insists that his play is entirely new: ‘Now, Sir, because I’ll do nothing here that ever was done before, instead of beginning with a Scene that discovers something of the Plot I begin this play with a whisper’:

PHYSICIAN: But yet some rumours great are stirring; and if Lorenzo should prove false (which none but the great Gods can tell) you then perhaps would find that – [Whispers.]

BAYES: Now he whispers.

USHER: Alone, do you say?

PHYSICIAN: No; attended with the noble – [Whispers.]

BAYES: Again.

USHER: Who, he in gray?

PHYSICIAN: Yes; and at the head of – [Whispers.]

BAYES: Pray, mark.

USHER: Then, Sir, most certain, ’twill in time appear. These are the reasons that have mov’d him to’t; First, he – [Whispers.]

BAYES: Now the other whispers.

USHER: Secondly, they – [Whispers.]

BAYES: At it still.

USHER: Thirdly, and lastly, both he, and they – [Whispers.]

BAYES: Now they both whisper. [Exeunt Whispering.]63

‘The Mystery’ is closely modelled on this whispering scene. Austen’s playlet is comprised of a series of interruptions and non-communications. It opens with a mock mysterious line, ‘But hush! I am interrupted!’, and continues in a similarly absurd and nonsensical manner:

DAPHNE: My dear Mrs Humbug how dy’e do? Oh! Fanny, t’is all over.

FANNY: Is it indeed!

MRS HUMBUG: I’m very sorry to hear it.

FANNY: Then t’was to no purpose that I …

DAPHNE: None upon Earth.

MRS HUMBUG: And what is to become of? …

DAPHNE: Oh! thats all settled. [whispers Mrs Humbug]

FANNY: And how is it determined?

DAPHNE: I’ll tell you. [whispers Fanny]

MRS HUMBUG: And is he to? …

DAPHNE: I’ll tell you all I know of the matter. [whispers Mrs Humbug and Fanny]

FANNY: Well! now I know everything about it, I’ll go away.

MRS HUMBUG & DAPHNE: And so will I. [Exeunt]

(MW, p. 56)

The play ends with a further whispering scene, where the secret is finally whispered in the ear of the sleeping Sir Edward: ‘Shall I tell him the secret? … No, he’ll certainly blab it … But he is asleep and won’t hear me … So I’ll e’en venture’ (MW, p. 57). In ‘The Mystery’, we are never told any information about the conversations between the characters, and it becomes as incongruous as Bayes’s own ‘new’ play, which he proudly insists has no plot.

Austen’s third playlet, ‘The First Act of a Comedy’, parodies musical comedy, an extremely popular mode of dramatic entertainment in the latter part of the eighteenth century.64 A satirical passage from George Colman’s New Brooms (1776) targets the vogue for comic opera:

Operas are the only real entertainment. The plain unornamented drama is too flat, Sir. Common dialogue is a dry imitation of nature, as insipid as real conversation; but in an opera the dialogue is refreshed by an air every instant. – Two gentlemen meet in the Park, for example, admire the place and the weather; and after a speech or two the orchestra take their cue, the musick strikes up, one of the characters takes a genteel turn or two on the stage, during the symphony, and then breaks out –

When the breezes

Fan the trees-es,

Fragrant gales

The breath inhales,

Warm the heart that sorrow freezes.65

Austen, like Colman, satirises the artificiality of the comic opera, its spontaneous outbursts of songs, and distinctive lack of plot.66 Austen’s playlet concerns the adventures of a family en route to London, and is set in a roadside inn, a familiar trope of the picaresque form popularised in Fielding’s novels Joseph Andrews and Tom Jones.67 Austen’s play also nods towards Shakespeare’s comic scenes set in ‘The Boar’s Head’ in Henry IV, Parts One and Two. Three of the female characters are called ‘Pistoletta’, ‘Maria’ and ‘Hostess’.

Chloe, who is to be married to the same man as Pistoletta, enters with a ‘chorus of ploughboys’, reads over a bill of fare and discovers that the only food available is ‘2 ducks, a leg of beef, a stinking partridge, & a tart’. Chloe’s propensity for bursting into song at any given moment echoes Colman’s burlesque of the inanities of comic opera: ‘And now I will sing another song.’

SONG

I am going to have my dinner,

After which I shan’t be thinner,

I wish I had here Strephon

For he would carve the partridge

If it should be a tough one.

CHORUS

Tough one, tough one, tough one,

For he would carve the partridge if it should be a tough one.

(MW, p. 174)68

As will be seen in the next two chapters, Austen clearly enjoyed musical comedy, even if, like Colman, she was conscious of its deficiencies as an ‘imitation of nature’.

The three playlets in the juvenilia are parodic and satirical, and a strong sense prevails that Austen was writing to amuse her sophisticated, theatre-loving brothers. Whether she was composing a mocking counterpart to Berquin’s instructive dramatic dialogues, or writing burlesques in the style of plays like The Rehearsal and The Critic, she endeavoured to impress her siblings with her knowledge of the drama. Two of her playlets, ‘The Mystery’ and ‘The First Act of a Comedy’, allude specifically to what was popular on the London stage, and mock it by drawing attention to its limitations and artificiality. ‘The Visit’ nods to the popular comedy High Life Below Stairs, so often dramatised for the private theatre, and begins to explore the incongruities and absurdities of genteel social behaviour.