Полная версия:

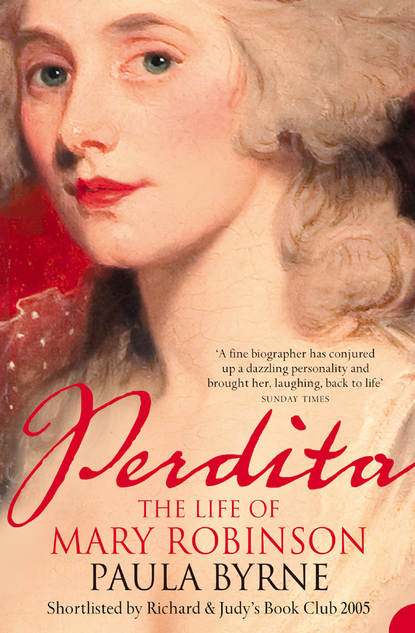

Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson

Several of the poems were modelled on the work of Anna Aikin (later Barbauld): ‘The Linnet’s Petition’, for example, was an imitation of her ‘The Mouse’s Petition’. Women’s poetry of the period was often written in the form of verse letters. Mary’s ‘Epistle to a Friend’ is written with a lightness of touch and warmth of feeling:

Permit me dearest girl to send

The warmest wishes of a friend

Who scorns deceit, or art,

Who dedicates her verse to you,

And every praise so much your due,

Flows genuine from her heart.13

One is left wondering about the identity of the friend, especially as the following poem is an elegy ‘On the Death of a Friend’, which ends ‘May you be number’d with the pure and blest, / And Emma’s spirit be Maria’s guard.’ We know hardly anything about Mary’s female companionship of these early years, beyond a passing reference in the Memoirs to her close friendship with a talented, witty, and literary-minded woman called Catherine Parry. In Mary’s last years, by contrast, she was sustained by a large circle of intellectually accomplished women. The only one of these early poems with a clearly identifiable biographical subject is an elegy on the death of the ‘generous’ Lord Lyttelton, whose poems were among the first that Mary loved. Needless to say, it makes no mention of the younger Lord Lyttelton.

The one poem in the collection that has real merit, and that deserves to be anthologized, is a ‘Letter to a Friend on leaving Town’. The virtue of a simple country life as against the vice of indulgence in the city was a common poetic theme in the period, but here there is a real sense of Mary writing from experience:

Gladly I leave the town, and all its care,

For sweet retirement, and fresh wholsome air,

Leave op’ra, park, the masquerade, and play,

In solitary groves to pass the day.

Adieu, gay throng, luxurious vain parade,

Sweet peace invites me to the rural shade,

No more the Mall, can captivate my heart,

No more can Ranelagh, one joy impart.

Without regret I leave the splendid ball,

And the inchanting shades of gay Vauxhall,

Far from the giddy circle now I fly,

Such joys no more, can please my sicken’d eye.

Although Mary adopts the conventional pose of condemning fashionable London life, all her poetic energy belongs to that life – her heart is still captivated by Ranelagh and Vauxhall. Yet she also has the maturity to see their dangers. At the centre of the poem is a telling portrait of the society belle who loses her looks, and thus the interest of the gentlemen of fashion, but remains addicted to the treadmill of the social calendar:

Beaux without number, daily round her swarm,

And each with fulsome flatt’ry try’s to charm.

Till, like the rose, which blooms but for an hour,

Her face grown common, loses all its power.

Each idle coxcomb leaves the wretched fair,

Alone to languish, and alone despair,

To cards, and dice, the slighted maiden flies,

And every fashionable vice apply’s,

Scandal and coffee, pass the morn away,

At night a rout, an opera, or a play;

Thus glide their life, partly through inclination,

Yet more, because it is the reigning fashion.

Thus giddy pleasures they alone pursue,

Merely because, they’ve nothing else to do;

Whatever can afford their hearts delight,

No matter if the thing be wrong, or right;

They will pursue it, tho’ they be undone,

They see their ruin, – yet still they venture on.14

This poem – an accomplished piece of work for a 17-year-old girl – was almost certainly written when Mary was moving in the fashionable circles of London society. It is at one level an anxious imagining of her own future fate. But seeing it in print, she must have wished she was back gliding her life away in the world of ‘scandal and coffee’ rather than languishing in the Fleet surrounded by women whose good looks had been worn down by penury.

Mary knew that her own beauty was fragile. She wrote in the Memoirs of how during her ‘captivity’ in prison her health was ‘considerably impaired’. She declined, however, to ‘enter into a tedious detail of vulgar sorrows, of vulgar scenes’.15 At this point in the original manuscript of the Memoirs several lines are heavily crossed out. It is impossible to decipher the words beneath the inking over, but there just might be a reference to pregnancy. It is therefore striking that the malicious but well-informed John King wrote in his Letters from Perdita to a Certain Israelite: ‘the Husband took refuge in the Fleet, immured within whose gloomy Walls they pined out Fifteen Months in Abstemiousness and Contrition, where her constrained Constancy gave birth to a Female Babe, distorted and crippled from the tight contracted fantastic Dress of her conceited Mother’.16 Since ‘Fifteen Months’ is an exactly correct detail, we cannot immediately dismiss King’s other piece of information about this period: his startling claim that Mary had a baby while in prison. ‘Distorted and crippled’ is certainly not a description of the lovely little Maria Elizabeth. Could it then be that the deleted passage in the Memoirs referred to a miscarriage or an infant death?

Imprisonment for debt was known as ‘captivity’, and this gave Mary the title for a new poem, much her longest work to date. Written in an overblown style, it is a plea on behalf of the wives and children of imprisoned debtors:

The greedy Creditor, whose flinty breast

The iron hand of Avarice hath press’d,

Who never own’d Humanity’s soft claim,

Self-interest and Revenge his only aim,

Unmov’d, can hear the Parent’s heart-felt sigh,

Unmov’d, can hear the helpless Infant’s cry.

Nor age, nor sex, his rigid breast can melt,

Unfeeling for the pangs, he never felt.17

‘Captivity’ was published in the autumn of 1777, just over a year after the Robinsons’ release from the Fleet. It was accompanied by a poetic tale of marital infidelity called ‘Celadon and Lydia’, into which Mary presumably poured some of her anger over Robinson’s philandering. This second volume of poetry was more handsomely produced than the first. Albanesi provided an elegantly engraved title page and the book bore a dedication guaranteed to grab attention: it was inscribed ‘by Permission, to her Grace the Duchess of Devonshire’. The dedication described the Duchess as ‘the friendly Patroness of the Unhappy’ author and ended by ‘repeating my Thanks to you, for the unmerited favors your Grace has bestowed upon, Madam, Your Grace’s most obliged and most devoted servant, MARIA ROBINSON’.

Georgiana Spencer was Mary’s exact contemporary in age, but came from a very different background: born into one of England’s most illustrious aristocratic families in 1757, she became Duchess of Devonshire and mistress of Chatsworth – one of the greatest houses in England – in the summer of 1774, just before the Robinsons went on the run from their creditors. She was already cutting a spectacular figure in London society. Someone mentioned to Mary that Georgiana was an ‘admirer and patroness of literature’. Mary arranged for her little brother George, an extremely handsome boy, to deliver to the Duchess a neatly bound copy of her first collection of poems. She also enclosed a note ‘apologizing for their defects, and pleading my age as the only excuse for their inaccuracy’.18 Georgiana admitted George and asked particulars about the author, as Mary no doubt expected. Georgiana was touched by the plight of the young mother sharing her husband’s captivity. She invited Mary to Devonshire House, her magnificent town residence in Piccadilly, the very next day. Robinson urged her to accept the invitation and she duly went, dressed modestly in a plain brown satin gown.

Mary was mesmerized by the Duchess’s look and manner: ‘mildness and sensibility beamed in her eyes, and irradiated her countenance’. Georgiana listened to her story and expressed surprise at seeing such a young person experiencing ‘such vicissitude of fortune’. With ‘a tear of gentle sympathy’, she gave her some money. She asked Mary to visit again, and to bring her daughter with her. Mary made many visits to her new friend – the two women both beautiful and cultivated, but in such contrasting circumstances. Mary described the Duchess as ‘the best of women’, ‘my admired patroness, my liberal and affectionate friend’.19 They would continue to be closely acquainted for many years. Georgiana loved to hear the particulars of Mary’s sorrows: her father’s desertion, her poverty, her unfaithful husband, her troubles as a young mother, her captivity. She shed tears of pity as she heard the story. Inspired by the Duchess’s patronage, Mary finished the poem that put her reflections on prison life into heroic couplets.

Mary remained unwaveringly loyal to those who helped her. She loved the Duchess and years later paid tribute in verse to her great qualities. She was particularly gratified by her friendship at a time when numerous female companions of happier days had deserted her. It was with the latter in mind that she wrote in her Memoirs of how ‘From that hour I have never felt the affection for my own sex which perhaps some women feel.’ She added with uncharacteristic bitterness: ‘Indeed I have almost uniformly found my own sex my most inveterate enemies … my bosom has often ached with the pang inflicted by their envy, slander, and malevolence.’20 This outburst is, however, belied by the female friendships that she forged and sustained throughout her life.

As spouse of a debtor, she was free to come and go, but the visits to Georgiana were the only time she ever left the Fleet. While she was away from the prison being entertained in the splendour of Devonshire House, Robinson took the opportunity to do some entertaining of his own: Albanesi procured prostitutes for him and brought them into the prison. If the Memoirs are to be believed, after a while Mary was humiliated even further when her husband took to sleeping with prostitutes while she and little Maria Elizabeth were in the very next room. When she confronted him, he brazenly denied the charges.

Despite Albanesi’s supposed responsibility for Tom’s infidelities, the Italian engraver and his glamorous Roman wife became the Robinsons’ closest friends among their fellow detainees. The wife, Angelina, was formerly mistress to a prince and subsequently the lover of the Imperial Ambassador, Count de Belgeioso. Unlike Mary, she chose not to share her husband’s captivity, but she paid frequent visits, dressed to the nines and comporting herself like a duchess. She was a fascinating older woman, in her thirties, a ‘striking sample of beauty and of profligacy’ who gave Mary an insight into the life of a courtesan. She always insisted on visiting Mary when she came to see Albanesi, and she would ridicule the teenage bride for her ‘romantic domestic attachment’. She told Mary that she was wasting her beauty and her youth; she ‘pictured, in all the glow of fanciful scenery, the splendid life into which I might enter, if I would but know my own power, and break the fetters of matrimonial restriction’.21 She suggested that Mary should place herself under the protection of rake and celebrated horseman, Henry Herbert, the Earl of Pembroke – she had already told him about Mary and his lordship was ready to offer his services.

Mary blamed Angelina for trying to persuade her into a life of dishonour. Both the Albanesis filled her young head with tales of ‘the world of gallantry’. Despite the disapproval of the couple expressed years later in the Memoirs, Mary was obviously enthralled by the way in which they offered a window into another world – a world that she had briefly tasted and must have longed to return to. Albanesi sang and played various musical instruments with easy accomplishment. And he told good jokes: Mary would herself become a notable wit.

On 3 August 1776, Robinson was discharged from the Fleet. He had managed to set aside some of his debts and give fresh bonds and securities for others. Mary wrote to her ‘lovely patroness’ with the news – she was at Chatsworth – and received a congratulatory letter in return. At the first possible opportunity, Mary headed for Vauxhall: ‘I had frequently found occasion to observe a mournful contrast when I had quitted the elegant apartment of Devonshire-house to enter the dark galleries of a prison; but the sensation which I felt on hearing the music and beholding the gay throng, during this first visit in public, after so long a seclusion, was indescribable.’22

*Sometimes called Mary and sometimes Maria (both by her mother and herself) – I will call her Maria Elizabeth throughout, to distinguish her from her mother.

CHAPTER 6 Drury Lane

The invitation to meet the new actresses was whispered as though they were meditating to exhibit something monstrous and extraordinary … She had engaged in a profession which vulgar minds, though they are amused by its labours, frequently condemn with unpitying asperity. She was engaging, discreet, sensible, and accomplished: but she was an actress, and therefore deemed an unfit associate for the wives and daughters of the proud, the opulent, and the unenlightened.

Mary Robinson, The Natural Daughter

Though Mary was thrilled to be back on the social scene at Vauxhall, the Robinsons had no means of sustaining their expensive lifestyle. Tom was still up to his ears in debt; he had failed to complete his legal apprenticeship and his father refused to aid him. Mary’s poems were not going to make her serious money, so once again she turned her mind to the theatre. This time she was not going to let her husband or her mother stop her. Now that he needed the money, Tom’s scruples about the profession swiftly evaporated.

The Robinsons took lodgings with a confectioner in Old Bond Street, near to London’s main shopping thoroughfare. Walking one day in St James’s Park with her husband, Mary met the actor William Brereton, who was soon to marry her school friend, the actress Priscilla Hopkins.* He joined them for dinner. He had seen Mary’s rehearsals with Garrick and was enthusiastic when she told him that she was thinking of reactivating her stage career. Some time later, when the Robinsons had moved to ‘a more quiet situation’ in the form of ‘a very neat and comfortable suite of apartments in Newman-street’,1 Brereton appeared unexpectedly one morning with his friend, the playwright and theatre manager of Drury Lane, Richard Brinsley Sheridan.

Sheridan had been a schoolfellow with Tom Robinson at Harrow, but Tom encountered a very different man from the shy and shabby boy he had once known. Sheridan had taken over from Garrick on the great man’s retirement in 1776 and looked set to shine even brighter. He had all the right credentials: a playwright, the son of an actor-manager and a writer, the son-in-law of a renowned musician; his wife was a musician of rare gifts, the beautiful Elizabeth Linley. Sheridan had caused a scandal when he had eloped with Miss Linley and fought two duels in her honour. Drawing on his celebrity, in 1775 he rocked London with a play based on his amorous adventures, The Rivals. Though not conventionally handsome, with his florid complexion and rugged features, he was clever and charming, renowned for his wit and talent.

When Sheridan called on Mary at her home, he was just months into his new role as manager of the most famous theatre in London and was scouting for talent. Mary found Sheridan’s demeanour ‘strikingly and bewitchingly attractive’. He in turn was entranced by her beauty and asked her to read for him. Looking back, she remembered that she was not dressed properly, a state in which she always felt insecure. She was several months into a further pregnancy and her health was poor – she attributed this to the combined influence of the pregnancy and her continuance in breastfeeding Maria Elizabeth even though the girl was nearly 2. But she agreed to read some passages from Shakespeare. Mary was gratified that the celebrated Sheridan proved so gentle and encouraging. They were to become great friends. He asked her to prepare for a public trial, and read with her himself.

Then Sheridan got Garrick on board. With extraordinary loyalty to the girl who had let him down three years before, he agreed – despite ill health – to come out of retirement and tutor her once again. Garrick and Sheridan decided on Juliet for her debut role, in Garrick’s own adaptation of the play. Brereton would be Romeo. Mary ran through Juliet’s lines for the first time in the green room at Drury Lane. Garrick was ‘indefatigable at the rehearsals; frequently going through the whole character of Romeo himself, until he was completely exhausted with the fatigue of recitation’.2 Mary never forgot Garrick’s kindness and his willingness to give her a second chance. When he died three years later, she wrote an elegy in his memory:

Who can forget thy penetrating eye,

The sweet bewitching smile, th’ empassion’d look!

The clear deep whisper, the persuasive sigh,

The feeling tear that Nature’s language spoke?3

Mary’s stage debut was set for 10 December 1776. It was announced to the press some time in advance. Managers often paid newspapers to ‘puff’ their actors. Sheridan and Garrick both had reputations for their publicity skills: Sheridan had planted an article in the Morning Chronicle puffing The Rivals after its initial failure. Garrick owned shares in various newspapers and his friendship with the journalist Henry Bate ensured favourable reviews and publicity for his plays. So it was that a great deal was made of Mary’s educated background and ‘superior understanding’. Sheridan and Garrick’s choice of role was astute: they knew that the press would be very forgiving towards a beautiful young woman playing Juliet for the first time. Mary, meanwhile, took the prudent step of writing to Chatsworth to inform Georgiana of her intentions. It was vital to get the patronage of the ladies, as many theatrical prologues of the period testify. The Duchess gave her approval to her young protégée and with ‘zeal bordering on delight’ Mary readied herself for her debut.4

What was the theatre like when Mary Robinson first stepped onto the boards of Drury Lane? The Licensing Act of 1737, which had been introduced in order to keep a check on plays satirizing the Government, confined legitimate theatrical performances to two patent playhouses in London, the Theatres Royal Drury Lane and Covent Garden. During the summer season when the two licensed theatres were closed, the ‘Little Theatre’ in the Haymarket had a summer patent. Drury Lane, London’s oldest theatre, had at this time a seating capacity of about two thousand. In the late Georgian period theatre was an essential part of fashionable life. A vibrant cross-section of the London community came to sit in box, pit, and gallery. Liveried servants were sent to reserve seats when the doors opened at five o’clock in the afternoon. Critics and raffish young men paid three shillings each to squash onto a bench in the pit; the well-to-do sat in private boxes for five shillings; honest citizens and visitors to town crammed into two-shilling places in the first gallery; servants and the hoi polloi sat in the upper gallery for one shilling. An evening entertainment ran to about four hours. First there was an overture played by the orchestra, then the main play (a drama, musical, or opera), then an interlude (music or a dance), and then a shorter afterpiece, usually of a farcical kind. It was generally said that the main pieces were for the ‘quality’ and the afterpiece for the commoners. Certainly the upper galleries filled up halfway through the main performance, when punters could gain admission for half price at the end of the third act of a five-act play.

Garrick had transformed the theatrical profession. In 1762 he had banned the audience from sitting on the stage – previously drunken patrons occupying the stage seats had been known to molest actresses (on one infamous occasion a near rape took place in full view of the audience). He had also made major modernizations in lighting and scenery: he removed the great chandeliers from their traditional place above the stage and substituted them with oil lamps in the wings, which had tin reflectors attached and could be directed towards or away from the stage, giving a greater control over illumination. The waxing or waning of light at dusk or dawn could now be indicated. Garrick also employed the ingenious scene designer Philip de Loutherbourg, who specialized in stage illusions. He charmed his audiences by changing the tints of the scenery, throwing light through coloured silk screens that turned on pivots in the flies and wings. De Loutherbourg was thus able to conjure up moonlight, cloud and fire effects. House lights were not turned down, as the audience came to the theatre to look at each other as much as to look at the players.

When Mary made her debut, she was acting in the newly renovated theatre, recently remodelled by the celebrated Adam brothers. The ceiling had been raised 12 feet, improving the acoustic and giving a sense of space; it was designed in a sumptuous pattern of octagonal panels that rose from an exterior circular frame, diminishing towards the centre, giving the effect of a dome. The side boxes had also been heightened, with an improved view of the stage; they were decorated along the front with variegated borders inlaid with plaster festoons of flowers and medallions. The old square heavy pillars had been removed from each side of the stage and replaced with elegant slim pillars, inlaid with green and crimson plate glass, which supported the upper boxes and galleries. The boxes were lined with crimson spotted paper. New gilt branches with two candles each replaced the old chandeliers. The boxes in the upper tier – known as the ‘green boxes’, where prostitutes solicited rich patrons – were adorned with gilt busts, painted embellishments and gilt borders. There was crimson drapery edged with gold fringing over the stage.

The theatre was not, of course, decorated in any such way in the backstage space where Mary spent most of her time. This was a vast area – larger than the entire front of house – with a maze of stairs and passages, some of them sloped to take wheels and animals. There were twenty dressing rooms, with a dresser allocated to each room, though principal players usually had their own personal dressers. It was later rumoured that Elizabeth Armistead – actress, courtesan, and rival to Perdita – began her career as Mary’s dresser. The dressing rooms, unlike the auditorium, had stoves to keep the actors warm. Some even had water closets. Other water closets were in the corridor adjacent to the stage area. The ladies’ dressing rooms had a candle and a mirror for each actress, their space demarcated by chalk marks across the floor. A hairdresser would have prepared Mary’s coiffure, but actresses put on their own make-up, a powder compounded with a liquid medium, which was often harmful to the skin and sometimes extremely dangerous, especially if white lead was used in its composition. White skin and rouged cheeks was the favoured image. In the green room, immediately to the side of the stage, actors, singers, and their invited friends mingled before the performance began.

The theatre was crowded on 10 December, the audience anxious to see Garrick’s protégée who was now also Sheridan’s new discovery. She had been advertised on the playbill as ‘A Young Lady (1st appearance upon any stage)’. For Mary herself it was a frightening experience. She was exceedingly nervous, mindful of the critics in the pit and Garrick sitting there with his shrewd, intense stare. The fate of a play (and an actor) was sealed on the opening night even before the curtain fell on the concluding act.

Theatre audiences did not sit in darkness and silence as they do today. The atmosphere was boisterous, voluble and interactive; the lighted auditorium helped to establish a rapport between spectators and actors. Applause or hisses rang out throughout the performance, and it was the audience rather than the critics who determined whether there was to be a long run or a speedy closure. The audience in the lobby and auditorium put on a display of its own: the young men in the pit, who were probably the most attentive spectators, offered criticism and comment; cheers and jeers could be expected from the gods (the one-shilling galleries), accompanied by songs, laughter, and flying fruit. It was not only rotten fruit that was hurled at bad performers – broken glass tumblers, metal, and wood could also rain down onto the stage. Despite having a reputation for drunken and unruly behaviour, those in the cheap seats usually paid attention once the play had begun and they were satisfied all was well. Less attentive were the aristocracy and gentry in the boxes, where fashionable society peered at itself as if in a mirror. As Mr Lovel, the fop in Fanny Burney’s contemporaneous novel Evelina, says, ‘I seldom listen to the players: one has so much to do in looking at one’s acquaintance, that, really, one has no time to mind the stage.’5