Полная версия:

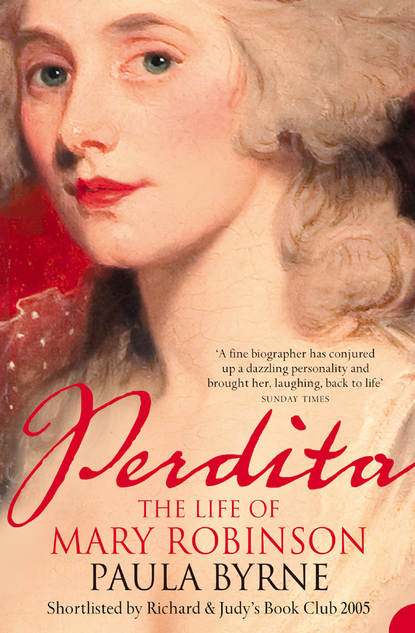

Perdita: The Life of Mary Robinson

King left his readers in no doubt that Mary and Lyttelton had a full-scale affair. He told of how they would engage in amorous dalliance in a closed carriage, with Robinson riding ‘a Mile or Two behind on Horseback’. Far from taking umbrage at the intimacy, the husband ‘continually boasted among his Acquaintance, the Superiority of his Connections, and his Wife’s Ascendancy over every fashionable Gallant’.21 This was the kind of story that gave Robinson a reputation as little better than his wife’s pimp.

A garbled and exaggerated version of this story about Mary making love in a moving coach with the full complaisance of her husband also found its way into the muckraking Memoirs of Perdita published in 1784. Here, though, her high-speed dalliance is with a well-endowed sailor who gives her ‘a pleasure she never could experience in the arms of debilitated peers and nobles’. He takes her four times, with Thomas Robinson riding not on a horse somewhere behind, but on the roof of the very carriage.22

King also claimed that Lyttelton intervened to save Robinson from prosecution when his fraudulent financial dealings were on the point of being exposed. According to this account, Lord Lyttelton dropped Mary on discovering that she and her husband were mere swindlers out to fleece him for all they could get. The truth of the matter is probably somewhere in the middle between Mary’s picture of aristocratic villainy and King’s far from disinterested portrayal of sexual misconduct for financial ends. There can be no doubt that the Robinsons lived way beyond their means: was it only the Jewish moneylenders who gave them the capacity to do so? Or did Lyttelton dig deep into his pocket? And if he did, was it in expectation of sexual favours or as payment for delights already delivered?

Whatever the precise means, Mary’s beauty, wit, and connections were taking her well on the way to the achievement of her ambition of fame: ‘I was now known, by name, at every public place in and near the metropolis.’23 At the same time, the Robinsons were becoming notorious for their debts. In the autumn of 1774, in the final weeks of her pregnancy, their creditors foreclosed on them and an execution was brought on Robinson. The couple were forced to flee Hatton Garden for a friend’s house in Finchley, which was then a village on the outskirts of London. They were deserted by all of their staff with the exception of a single faithful black servant. Mary barely saw her husband, who spent most of his time in town.

In the meantime, Hester returned from Bristol with George and helped her daughter to prepare for her confinement. They sewed baby clothes, and Mary continued to read and write. Robinson acquired the habit of taking George with him on his ‘business trips’ to London, but George, who adored his sister, confessed that they called upon disreputable women. He also told her that her valuable watch, which Mary presumed had been taken by the bailiffs, had actually been given to one of Robinson’s mistresses. When confronted, he did not bother to deny the infidelity.

Despite Robinson’s indifference, which was particularly insensitive so close to the birth of his first child, Mary continued to blame others more than her husband for their predicament. Perhaps she felt guilty for contributing to his debts by her expensive taste. She blamed Lyttelton, their creditors and even Robinson’s father: ‘had Mr Harris generously assisted his son, I am fully and confidently persuaded that he would have pursued a discreet and regular line of conduct’.24

It was to Harris that Robinson turned in desperation. He decided to leave London and head for Tregunter, where he could plead for his father’s help. Robinson insisted that Mary accompany him, despite the discomfort and danger of travelling all those miles in her condition. He no doubt anticipated that the presence of his favoured young wife heavy with a future grandchild would help to soften up old Harris. Mary, for her part, did not want to leave her mother when she needed her during the trials of labour. Childbirth was traumatic at the best of times for women in the eighteenth century: it was common for mothers to write their unborn children farewell letters to be read in the event of their death during labour or its aftermath. Mary feared that she might die in Wales and the baby be left amongst strangers. With her youthful pride, she also dreaded the sneers she would have to face from Elizabeth Robinson and Mrs Molly upon returning to Tregunter in debt and disgrace.

CHAPTER 5 Debtors’ Prison

‘Tis not the whip, the dungeon, or the chain that constitutes the slave; freedom lives in the mind, warms the intellectual soul, lifts it above the reach of human power, and renders it triumphant over sublunary evil.

Mary Robinson, Angelina

News had reached Tregunter of Robinson’s imminent arrest. Harris was away from home when they arrived, but on his return he lost no time in making his position clear: ‘Well! So you have escaped from a prison, and now you are come here to do penance for your follies?’1 Over the following days, he taunted the couple, though he did at least offer them refuge.

When Mary tried to amuse herself by playing an old spinet in one of the parlours, Harris mocked her for giving herself airs and graces: ‘Tom had better married a good tradesman’s daughter than the child of a ruined merchant who was not capable of earning a living.’ She may have smarted from the insults, but her husband, knowing her temper, pleaded with her to ignore Harris’s behaviour. She was furious, though, when he openly insulted her at a dinner party. A guest, remarking on her swollen stomach, expressed his pleasure that she was come to give Tregunter ‘a little stranger’ and joked (as Harris was renovating his house) that they should build a new nursery for the baby. ‘No, no,’ replied Mr Harris, laughing, ‘they came here because prison doors were open to receive them.’2

The renovation of Tregunter meant that Mary could not be housed for her confinement – at least that was the excuse given by Harris. Only two weeks away from giving birth, Mary was told that she must go to Trevecca House, which was just under two miles away, at the foot of a mountain called Sugar Loaf. Away from Harris and his female cronies, she relaxed and communed with nature:

Here I enjoyed the sweet repose of solitude: here I wandered about woods entangled by the wild luxuriance of nature, or roved upon the mountain’s side, while the blue vapours floated round its summit. O, God of Nature! Sovereign of the universe of wonders! in those interesting moments how fervently did I adore thee!3

The sentiments are typical of the age of sensibility. If she really wandered thus so late in her pregnancy, she must have been unusually healthy and energetic.

Though Mary writes here of the ‘sweet repose of solitude’, Trevecca House was actually more crowded than Tregunter. One part housed the Huntingdon seminary and another part of the building was converted into a flannel manufactory. Nevertheless, she was no longer forced to endure the jibes of her husband’s vulgar family, for they seldom visited her. According to the Memoirs, she was indifferent to their ill-treatment of her. Her spiritual communion with the mountains made her all the more conscious that she had ‘formed an union with a family who had neither sentiment nor sensibility’.

The child, named Maria Elizabeth Robinson,* was born on 18 October 1774, just a few weeks before Mary’s seventeenth birthday. Delighted with her beautiful daughter, the young mother allowed her nurse to show Maria Elizabeth to the factory workers who clamoured to see the ‘little heiress to Tregunter’. Mary was at first alarmed at the prospect of exposing the baby to the cold October air, but the nurse soothed her fears and cautioned her that the local people would consider Mary ‘proud’ if she refused to show the ‘young squire’s’ baby. It was a happy day for Mary, as the crowd heaped blessings on the baby, and the nurse, Mrs Jones, passed on every detail of their praises to the exhausted mother.

There is no mention of Robinson in the narrative, but later that evening Harris paid a visit. After asking after Mary’s health he demanded to know what she was going to do with the child. When she made no answer he honoured her with his own recommendation: ‘“I will tell you,” added he; “Tie it to your back and work for it.’” For good measure he added, ‘Prison doors are open … Tom will die in a gaol; and what is to become of you?’ Mary was all the more humiliated by the impropriety of these taunts being spoken in front of the nurse. Maybe Harris would have been kinder if the baby had been a boy, but one senses that his own infatuation with Mary had now worn off and that he considered her expensive lifestyle to have been a major factor in Tom’s improvidence. When his daughter Elizabeth made her visit, she suggested that it would be a mercy for the infant ‘if it pleased God to take it’.4

Three weeks later, Robinson’s creditors caught up with him. They had discovered that he had fled to Wales, and in order to avoid the spectacle of being arrested at Harris’s house – which would have been the final nail in the coffin of his hoped-for inheritance – he left immediately. They were on the run once more. Though still weak from the delivery of her child, Mary refused to stay at Trevecca without her husband. She travelled against the advice of the capable Mrs Jones. They set off for Monmouth, where Mary’s grandmother lived. Mrs Jones travelled in the post chaise as far as Abergavenny, cradling the baby on a pillow on her lap. The local people were sorry to see them go, but ‘Neither Mr Harris nor the enlightened females of Tregunter expressed the smallest regret, or solicitude on the occasion.’5

Mary was worried about taking care of her baby after the departure of Mrs Jones. Her education had not prepared her for ‘domestic occupations’. She was still only 17, and without her mother. But she trusted her maternal instincts and did the best she could. Lacking a wet nurse, she breastfed her own baby, which was still perceived as an unusual step for a woman of her class – though it was something that would be advocated by the feminist writers of the 1790s.

The next day they arrived at Monmouth, where Mary’s grandmother Elizabeth lived. They received a warm welcome, though how much her grandmother knew about their state of affairs is not clear. Seventy-year-old Elizabeth, who had been a beauty in her day, was still an attractive woman; she dressed in neat, simple gowns of brown or black silk. She was a pious, well-respected figure, and mild of temper: Mary envied her grandmother’s tranquillity and her fervent religious faith.

Here at Monmouth they received ‘unfeigned hospitality’. There was a lively social scene. Once more Mary’s contradictory nature is revealed. Her favourite amusements were wandering by the River Wye and exploring the castle ruins: thus the woman of sensibility who would become one of the most successful Gothic novelists of the age. But she also loved company and attended local balls and dances: thus the lady of fashion who would become a fixture on the London social scene.

Determined not to let breastfeeding interfere with the chance to dance at a local ball, she once took Maria Elizabeth with her, so that she could feed her at intervals. After a particularly strenuous bout of dancing, she fed her in an antechamber. But something went wrong and by the time they arrived home the baby was in convulsions. Mary was hysterical, with the result that her milk would not then come at all, which left the baby parched and continuing to fit. Mary was convinced that her vigorous dancing and the excessive heat of the ballroom had affected her milk and brought on the fit. She stayed awake with Maria Elizabeth all night. In the morning, friends and well-wishers called to enquire after the infant. One such man was the local clergyman, who was moved to see the frantic young mother in such despair. Mary refused to let the baby be taken from her lap, but the clergyman begged her to let him try a home remedy that had been successful with one of his own children suffering the same way. Mixing aniseed with spermaceti, he gave the medicine to the baby and almost instantaneously the convulsions abated and she fell peacefully asleep.

Shortly after this episode, Tom Robinson once more heard that his creditors were about to catch up with him. Yet again, they prepared to travel before Robinson was arrested. But this time they were too late. An execution for a ‘considerable sum’ was served on him and the local sheriff of Monmouth arrived to arrest him. In the event, the sheriff, who knew Mary’s grandmother, took pity on them and offered to accompany the Robinsons back to London.

On returning to the metropolis, Mary hastened to her mother, who was now living in York Buildings just off the Strand. Hester was, of course, thrilled to see her new granddaughter. Robinson, in the meantime, discovered that the person responsible for alerting the sheriff was none other than his best friend Hanway. The latter’s excuse was that the debt in question was relatively small and he had assumed that Robinson’s father would have paid it. They came to an arrangement and patched up their friendship. The Robinsons then took lodgings in Berners Street, just north of Oxford Street.

Mary began to make arrangements to fulfil a secret ambition that she had been harbouring for many years. She now had ready for publication her first book of poems: she had been working on them even before her marriage. In her Memoirs, she spoke disparagingly of her first literary efforts as ‘trifles’; she expressed the hope that no copies survived, except for the treasured one that her mother had preserved. Regardless of the quality, her determination in preparing the volume in such difficult circumstances is impressive. She was also unusual among upwardly mobile women in undertaking the everyday care of her own baby. She insisted on dressing and undressing her daughter. The baby was breastfed and always slept in her presence, by day in a basket, by night in her own bed. Mary had heard horror stories about the neglect of servants towards children who were too young to tell tales, and she resolved only to let herself and Hester tend to the child.

Her devotion as a mother and her plans to become a published poet did not stop her from socializing, and she began visiting her old haunts such as Ranelagh with her female friends, while Tom kept a low profile. Mary had renewed confidence in her personal appearance and her deportment. She had grown taller in the last year and felt more worldly and sophisticated than when she had first broken upon the social scene two years earlier. She felt confident, serene, and was a little harder edged. The special occasion of her reappearance in London society is marked in her Memoirs by a description of a new dress. This one was of lilac silk with a wreath of white flowers for a headdress. ‘I was complimented on my looks by the whole party,’ she recalled, before stressing that her first concern was to be a good mother: ‘with little relish for public amusements, and a heart throbbing with domestic solicitude, I accompanied the party to Ranelagh’.6

As she entered the rotunda the first person she encountered was her old ‘seducer’ George Fitzgerald. He was startled to see her, but lost no time in greeting her, welcoming her re-entry into ‘the world’ and observing that she was without Robinson. He followed her for the remainder of the evening, and as she left she observed his carriage drawing up alongside hers. The next morning he arrived at the house to pay his respects, as she sat correcting proofs of her poetry, with her daughter sleeping in a basket at her feet. She was annoyed at the intrusion and her vanity was piqued by the fact that she was dressed in a matronly morning dress rather than ‘elegant and tasteful dishabille’. Papers were strewn over the table, making the room look like a cross between ‘a study and a nursery’.

She received him frostily. Undeterred, Fitzgerald complimented her on her youth and her child on her beauty. The attention to Maria Elizabeth led to a thaw. Fitzgerald then took a proof sheet from the table and read one of the pastoral lyrics, praising her efforts. ‘I smile while I recollect how far the effrontery of flattery has power to belie the judgment,’ Mary wryly notes in her Memoirs.7 She asked him how he had discovered her place of residence and Fitzgerald confessed that he had followed her carriage from Ranelagh the previous evening.

The next evening he returned and took tea with the Robinsons, inviting them to a dinner party at Richmond. Mary declined, but she and Tom tentatively began to socialize with their old friends. Returning to Ranelagh a few days later they reacquainted themselves with Lord Northington, Captain O’Byrne, Captain Ayscough, and the wicked Lord Lyttelton, who had not changed one bit and was – as only to be expected – ‘particularly importunate’.

For a few weeks it looked as if the Robinsons were embarking on their old life again, but then Tom was arrested on a debt of £1,200, consisting principally of ‘the arrears of annuities, and other demands from Jew creditors’. Mary insisted that the debts were all his own: ‘he did not at that time, or at any period since, owe fifty pounds for me, or to any tradesman on my account whatever’.8 Robinson stayed in custody in the sheriff’s office for three weeks. He felt too depressed even to go through the motions of trying to raise the money from his father or his friends. Prison was inevitable and he was duly committed to the Fleet on 3 May 1775. He would spend the next fifteen months there.

The Fleet housed about three hundred prisoners and their families. It was a profit-making enterprise: prisoners had to pay for food and lodging, pay the turnkey to let their families in and out, and even pay not to be kept shackled in irons. There were opportunities for work, though some inmates were reduced to begging from passers-by – a grille was built into the prison wall along Farringdon Street for this purpose.

It was not a requirement, but was nevertheless common, for wives to accompany their husbands to debtors’ prisons such as the Fleet, the Marshalsea and the King’s Bench. Mary did so – as her fellow novelist and poet Charlotte Smith would when her husband was confined a few years later. Often wives would come and go, bringing in for their confined husband. Young children were, however, usually left with relatives. It is a mark of Mary’s deep devotion to her baby that she took the 6-month-old Maria Elizabeth to prison with her rather than leaving her in the care of Hester. For that matter, she could presumably have stayed with Hester herself. Her loyalty to Tom Robinson is striking, especially in the light of his infidelities.

They were given quarters on the third floor of the towering prison block, overlooking the racquet ground, which the inmates were at leisure to use for exercise. Robinson – an ‘expert in all exercises of strength’ – played racquets daily while Mary tried her best to make a home in the squalid surroundings, and took care of her baby. She barely ventured outdoors during daylight hours for a period of nine months, though she did at least have a nurse to help her with the baby. The cells were small, dark, and sparsely furnished, but at least they were given a pair of rooms and not just one. This meant, however, that they paid extra for lodging, which meant that it would take longer to put aside the money to pay off the debt.

According to the memoirs of Laetitia Hawkins, a neighbour of Mary’s during her years of fame, Robinson was sent a guinea a week subsistence money by his father. He was also offered some employment ‘in writing’ – probably the copying of legal documents, an activity for which he was well trained – but he refused to do anything. Mary, by contrast, not only attended to her child but also ‘did all the work of their apartments, she even scoured the stairs, and accepted the writing and the pay which he had refused’.9

Less welcome offers of assistance came from the rakish lords, Northington, Lyttelton, and Fitzgerald. She knew, though, from the ‘language of gallantry’ and ‘profusions of love’ in their letters what the offers really meant. It was above all her maternal devotion that kept her from exchanging a life of poverty for the temporary comforts afforded to a courtesan.

At night, she would walk on the racquet court. One beautiful moonlit evening, she went out with her baby and the nursemaid. Mary would later remember it as the night when her daughter ‘first blessed my ears with the articulation of words’. They danced the child up and down, her eyes fixed on the moon, ‘to which she pointed with her small fore-finger’, whereupon a cloud suddenly passed over it and it disappeared. Little Maria Elizabeth dropped her hand slowly and, with what her mother perceived as a sigh, cried out ‘all gone’. These were her first words – a repetition of the phrase used by her nurse when she wanted to withhold something from the baby. In retrospect, it seemed like the one joyful moment in the long months of captivity. They walked until midnight, watching the moon play hide and seek with the clouds as the ‘little prattler repeated her observation’.10

Twenty years later, Mary’s friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge would make one of his loveliest poems out of a similar experience. Coleridge writes of how his infant son Hartley could recognize the song of the nightingale before he could talk:

My dear babe,

Who, capable of no articulate sound,

Mars all things with his imitative lisp,

How he would place his hand beside his ear,

His little hand, the small forefinger up,

And bid us listen!

He then tells of how one night when baby Hartley awoke ‘in most distressful mood’, he scooped him up and hurried out into the orchard

And he beheld the moon, and, hushed at once,

Suspends his sobs, and laughs most silently,

While his fair eyes, that swam with undropped tears,

Did glitter in the yellow moon-beam.11

Coleridge’s poem was written in April 1798, two years before Mary drafted this section of her Memoirs. It was published in Lyrical Ballads, a book she knew well (it would inspire the title of her final volume of poetry, Lyrical Tales). What is more, Coleridge visited her on several occasions in the early months of 1800, when she was writing the Memoirs. They subsequently wrote poems inspired by each other’s work. There can, then, be little doubt that the phrasing of her memory of Maria Elizabeth by moonlight – the idea of ‘articulation’, the baby’s raised forefinger, the dancing yellow light – was shaped by a memory of Coleridge’s poem for Hartley. Later in 1800, she paid a further compliment in the form of a lovely poem for Coleridge’s third son, Derwent.

It was only as a result of the literary revolution of the 1790s, in which Coleridge and Robinson each played an important part, that intimate memories of this kind became the stuff of poetry and autobiography. Mary’s early verse, published while she was in the Fleet, was stilted and artificial in comparison. Poems by Mrs Robinson, an octavo volume of 134 pages, was published in the summer of 1775, with a frontispiece engraved by Angelo Albanesi, a fellow prisoner who had been befriended by Tom. The volume garnered a mediocre notice in the Monthly Review: ‘Though Mrs Robinson is by no means an Aiken or a More, she sometimes expresses herself decently enough on her subject’ (Anna Aikin and Hannah More were the most admired ‘bluestocking’ poets of the age).12

The volume includes thirty-two ballads, odes, elegies, and epistles. For the most part, they consist of pastorals (‘Ye Shepherds who sport on the plain, / Drop a tear at my sorrowful tale’) and moral effusions (pious outbursts addressed to Wisdom, Charity, Virtue, and so forth) that are typical of later eighteenth-century poetry at its most routine. But a handful of the poems show signs of future promise: there are, for instance, some brief character sketches in which one may see the seeds of the future novelist’s voice.