Полная версия:

Look to Your Wife

He instigated other rules too. Report cards. If you failed, you would be sent down a year. A strict dress code. The girls now wore below-the-knee checked kilts, with long socks. Black or brown shoes, or you were sent home. Boys’ hair had to be no more than a number four cut. Ties were not to be tucked into shirts. Everyone must walk down the central aisle in silence into assembly. Students (no longer ‘pupils’) would stand when a teacher entered the room.

To create a sense of belonging, he instigated houses: Lennon, McCartney, Harrison, and Starr. The school was rebranded as SJA (St Joseph’s Academy). The initials appeared everywhere.

‘They deserve the same standards’, was Edward’s mantra. He brooked no dissent. ‘You are free to enrol your child elsewhere,’ he would tell the odd disaffected parent. But they never did. They all wanted their children to be part of a success story. He insisted that if ever he had children of his own, they would attend the school. He had no intention of having children, but this was a good way of putting pressure on the staff to set an example and do likewise with their own offspring.

One of Edward’s best interventions was securing funding for a Literacy Support Dog called Waffles. The kids from Starr house were a bit dim, and he figured it would be a novel way of improving their reading skills. The students would take it in turns to read to Waffles, who lay patiently in his basket. When they had finished reading their two pages loudly and clearly to Waffles, he would raise his head in expectation of his doggy treat (his favourites were Arden Grange crunchy bites). It was another huge success of Edward’s.

The GCSE results soared, as if by magic. When SJA won an award for Most Improved Academy in the North West, he organized cupcakes for the entire school and gave permission for lessons to be abandoned for the day. Again and again he emphasized that grades mattered.

The children, also, proved a doddle. From that first week when they returned to school after the summer holidays to find the playground marked out with football and basketball lines, they knew he was all right.

The staff were the problem. They were lazy, disaffected, gossipy, complacent. They loathed Oxbridge, and they probably loathed him, even though they were nice to his face. Januses. Except for Lisa. It was not so much that she disliked him; she just didn’t notice him. Towards the end of his first year, he decided to throw a party for the staff. He tried to pretend that it was to improve staff morale, to show that he was, after all, one of the guys: that he cared about his staff as much as he cared about his students. But he knew none of this was true. He wanted to see Lisa. He wanted to take her in his arms.

* * *

‘Will you come to the party?’

‘Yes, of course darling. May I bring Tabitha?’

‘Well as long as she doesn’t pee all over the flat. Or sleep on the bed.’

‘Fantastic. I’ll take the train. Tabitha prefers it that way. Can’t wait to see you, Ed. Guildford feels cold without you.’

* * *

‘Will you come to the party?’

‘Is it OK to bring my husband?’

‘Oh – do you know, I wasn’t aware that you were married. You’ve kept that quiet! But yes, of course it is. I’d love to meet him.’

‘Then I’ll come.’

CHAPTER 3

After the Party

The invitation asked everyone not to wear stiletto heels. This puzzled Lisa. What a curious detail. What on earth did the headmaster and his wife have against high-heeled shoes? It was only when she arrived and saw the beautifully polished wooden floors that she understood. The pinprick of heels would not be a good look in such an immaculate flat, although, personally, she preferred a shabby chic look. She once shocked her husband when she took out a hammer and violently pummelled a brand-new butcher’s block that had been delivered that morning from Ikea: ‘It needs to look old,’ Lisa explained, ‘as if it’s been around for centuries.’ Later, she rubbed oil into the indentations. She liked to press her fingers into the holes that she had made. She loved the feel of wood.

The textures of natural materials; beauty. These were things that mattered to Lisa. She was a working-class girl from Bootle. But she had a love of beautiful clothes. It came from her father. He had been a postman, and he had a gambling habit. When he won on the ‘gee-gees’ he would bring her and her sisters posh clothes from George Henry Lee. The next day her mother would return them. Lisa never forgot the quality and cut of the garments. She bought her first beautiful dress with the first instalment of her student grant. It was black silk, cut on the bias, with embroidered dull-gold roses. It was the first time she truly understood how beautiful clothes bestowed confidence.

Lisa had been educated at an all-girls’ convent school, run by the Sacred Heart Sisters. Sister Agnes, unintentionally, used to crack them up: ‘Girls, please remember, do not eat your sandwiches up St Anthony’s back passage.’

Lisa loved the school chapel, with its smell of polished wood and incense. The other girls were a nightmare, though. The height of their ambition was to get pregnant, so they could bag a council flat. But she also knew that these girls wanted a baby to love. She was sure about that. Sadly, the men they went for were such losers. She knew, with absolute clarity, that once she left, she would never go back.

On leaving school, she applied for a foundation course in textiles at the London School of Fashion. The long-term plan was Textiles in Practice, BA (Hons), at the Manchester School of Art, but first she had to complete a foundation course, and London was the natural choice. She adored London. It was her city, and always would be. She still remembered how naïve she had been when she first arrived. She blushed at the memory of seeing posters around the city saying ‘Bill Stickers will be prosecuted’. Who was this man Bill Stickers? Why hadn’t anyone caught him. Her new sophisticated southern friends cried with laughter when she asked them.

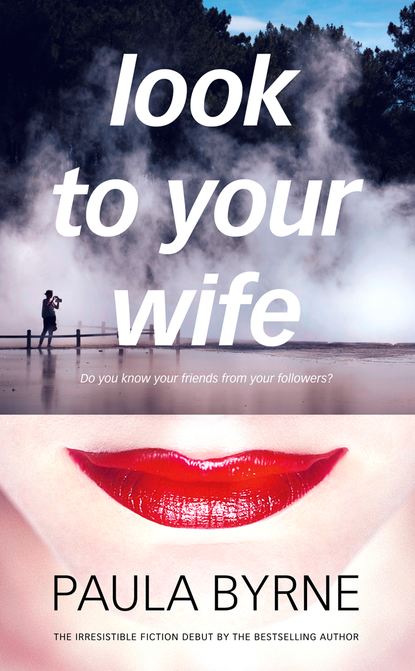

But she made it to Manchester, and after the BA came an MA for which she wrote a dissertation called Lipstick and Lies: Reassessing Feminism and Fashion. It was about third-wave feminism. How it was OK to embrace your femininity and still be a feminist. She traced the connection between fashion and female politics from 1781 to the present day. She began with the mother of feminism, Mary Wollstonecraft, arguing that her ideas about dress and women’s liberation were paradoxically close to those of Marie Antoinette, a fashion icon from the other end of the political spectrum. She ended with Alexander McQueen by way of Coco Chanel. She had always worshipped McQueen. She appreciated the wit and style of his final act of defiance: hanging himself with his best belt in a closet full of beautiful clothes.

She was passionate about her work. It was her solace, her consolation and her joy. But jobs teaching the history of fashion were as rare as hen’s teeth, and before she stood any chance of getting one she would have to spend three years working on a PhD thesis, earning no money. Things had also gone a bit pear-shaped in the boyfriend department, so she had returned home to Bootle. The next thing she knew, she had a job teaching textiles at St Joseph’s Academy, and a husband from New Brighton – a man who was never going to set the world alight, but who was dependable, and, it had to be said, incredibly handsome: he could have got a job as a Tom Cruise lookalike.

Lisa was just twenty-three, straight out of her MA, when she got the job. She was taken aside by a wise old teacher, Will Butler, who told her to go in hard. ‘Be firm, don’t give an inch. Show them who’s boss, and you will never have to discipline them again.’

Lisa took the advice to heart. She strode in, wearing a red jacket, and took no nonsense. Within hours, the gossip around the school was that Miss Blaize was ‘dead strict’. From then on, it was plain sailing. She had a laugh with the pupils, but with just one look she could command complete attention.

She learned another valuable lesson, early on, about schoolchildren and loyalty. It was towards the end of the school day, and she was tired. A boy called Michael Turner was giving her cheek. He was a redhead, and a clown, and he was trying to show off. ‘Miss, I can’t do it. Miss, I don’t understand. Miss, Tim’s kicking me under the table.’

Finally she snapped and slapped him across the face. Total silence. Utter horror. What had she done? Everyone looked at her. Then the bell rang.

‘Off you go. You’re dismissed.’

That night she told Pete, her husband, what she had done. He was shocked. ‘Lisa, you’ll lose your job. He’ll go straight home and tell his parents. You will have to resign. What on earth were you thinking?’

‘That was the problem. I wasn’t thinking. Well it’s too late now. There’s nothing I can do.’

All night she agonized over the slap. What had she been thinking? She planned on going to the head first thing in the morning and fessing up. Hold up your hand, mea culpa …

As it happened, she bumped into Turner in the playground. ‘Aright miss, see you later!’ He gave her a wide grin.

He never said a word. Nor did the other children. Loyalty. Children always have the ability to surprise teachers. He never gave her cheek again. But she still had nightmares about the slap.

Then there was Jordan. He was fourteen and the most handsome boy she had ever seen. He had huge hands, like Michelangelo’s statute of the boy/man David. She would catch Jordan’s eye in the classroom and he would respond with an intense stare. God, the boy was so bloody sexy. He disconcerted her. Made her feel that he was undressing her with his eyes. Then she would feel wracked with shame for having such thoughts about a schoolboy. Now I know how Humbert Humbert felt when he confessed that it was Lolita who seduced him, she said to herself. These were thoughts that she could never have voiced to anyone. Especially not to Pete, for whom the phrase ‘jealous guy’ might have been coined.

One day, Jordan stayed late in the textile room to help her tidy. She was stacking scissors into metal containers. Jordan was picking up tiny dressmaking pins with his oversized fingers. They were working in silence, but he suddenly broke down and told her that his parents were divorcing. She hugged him and kissed his forehead softly. And that was it. Just a chaste, butterfly-wing kiss. But she felt worse about that kiss than she had about slapping Turner. God, if anyone found out. Perhaps she wasn’t cut out for teaching.

She wanted to keep her options open. She was already thinking that she might not be cut out for marriage either. Pete had the most gorgeous body, but never said anything interesting.

She was a grafter, and always had been. At fourteen, she’d sold records in Woolworth’s. During her foundation year in London, she had worked nights as a hospital cleaner. While an undergraduate in Manchester, she had been a barmaid. So when she came home in the evenings, tired as she was from the noise of the school and the strain of being a new teacher, she sat at her computer and worked Lipstick and Lies up into a book. A small publisher took it on, and there were a few enthusiastic reviews in some little-known magazines and periodicals. It was even shortlisted for a prize so obscure that there couldn’t have been many competitors. She began thinking about a subject for a second book; one that might get her out of teaching.

* * *

She had to admit that she was rather attracted to the new head, and just a little excited about the party. She had pretended not to listen to his address in that first assembly back in the autumn; in reality, she had been mesmerized by his quiet but charismatic basso profundo voice, and the way that he spoke in perfectly formed sentences. His words had been like silk, his soft phrases a drug, a charm, a conjuration.

The day before the party, she found herself alone in the staffroom with Chuck Steadman, who had also applied for the headship. He had quickly overcome his disappointment and was making himself indispensable to the new man.

‘What do you really think of him?’ Lisa asked, fixing Chuck with her blue-grey eyes and twisting her hair around her index finger. Men always listened when she did that.

‘Edward is an only child,’ Chuck replied, ‘that says a lot about him. He told me he was once destined for the church. Don’t you think he would have made a good bishop?’

‘Oh, I see what you mean: Scott Fitzgerald’s “spoiled priest”. Yes, I see exactly what you mean. He speaks in a very reverential way. He’s shy underneath all that intellect and brilliance. But he’s certainly tough. He’s made a great start in turning this place around. Not an easy feat.’

‘Aha, you gotta hand it to him. He’s Mr God round here. Did you ever meet Mrs God?’

‘Not yet. She doesn’t come here very often, does she? I’m hoping she’ll be at the party tomorrow. I’ve heard she’s very posh, what do they say, very Edinburgh. She’s Scottish, isn’t she? I overheard one of my indiscreet sixth-formers saying that one Sunday night he’d been passing that old block of flats where the head lives, and he’d seen him stuffing a busty blonde holding a cat basket into a car. That must have been her. Not what I’d imagined he’d go for.’

‘Well, as a red-blooded Southerner, I approve of the Baywatch type. Why, look at my Milly!’

‘Very funny. Your wife’s the most gamine, chic Audrey Hepburn doppelgänger I’ve ever seen.’

‘Moira’s more of a Marilyn.’

‘Whatever. God knows how you persuaded Milly to marry a deadbeat like you!’

‘My American charm and charisma, no doubt. English women love American guys because they’re forthright and honest. Not like your English gentlemen, still in love with Nanny.’

‘Chuck, we are not living in Brideshead Revisited. You do make me laugh. Anyway, you seem to hero worship Edward. You’re never away from him. You still after his job?’

‘Of course I am! First I can be his wing man and then I can take his place. Seriously, though. I’m fed up teaching. I fancy a bit of admin responsibility. That’s why I had a shot at the headship myself, even though I knew I didn’t stand a chance. Look, I like him. He’s a nice guy. A good leader. He makes you want to be part of his winning team. That’s your trouble, Lisa. You don’t want to be part of any club that might accept you.’

* * *

Pete had refused to come to the staff party, though Lisa hardly pressed the issue. She was too selfish to look after him at a party. So she was alone and slightly nervous. To be honest, a little out of her depth. She didn’t usually mingle with the other staff, preferring to teach her classes, get into her Mini, and head home to work on ideas for her second book.

She looked around the room and saw a fascinating scenario unfolding. There were two beautiful, long-haired young women deep in conversation. One was a teacher at the school, the other a sixth-former. The teacher, Maia Riddell, filled the wine glass of the student. The student didn’t thank her. Lisa saw with instant clarity that they were lovers. It was simply impossible that a student would not thank her teacher. Now the evening was getting interesting.

Edward was watching her. She could feel it. But his wife was in the room, so he was being careful. He was biding his time. During a lull in the music, he approached and asked her to dance. She felt for his wife. But she wanted to dance: Lisa loved to dance. She had an odd feeling that Edward had orchestrated the evening so that it would end like this. They danced to k. d. lang’s ‘Constant Craving’. His wife’s eyes were boring into them, though she was pretending not to notice. Lisa told Edward about the lesbians.

‘Please be careful, Edward. I think this could blow up.’

‘No, no,’ he protested, ‘you’ve got this wrong. Maia Riddell is an exemplary teacher. She would never, ever hit on a student. But, Lisa, I thank you for your concern.’

‘Well, don’t say I didn’t warn you,’ she laughed.

* * *

There is always a green-light moment in every relationship, especially in a clandestine one. The moment when a couple can make a decision, stop what they’re doing, or just go ahead anyway. Lisa was no strict moralist when it came to relationships; she’d always had a loose notion of fidelity, but she wouldn’t go any further if there were children involved.

Edward and Lisa met for a drink in the local pub after work one day. He asked if she had children. ‘No,’ she said, ‘had my bellyful looking after my siblings thank you, to ever romanticize the idea of raising a family. I’d rather concentrate on my career. How about you?’

‘No. We’ve been married for seven years, and we have never wanted children. In fact, we left out the prayer for children in our marriage ceremony. We’re happy with our cat, Tabitha. I think my mother is disappointed. I don’t see Moira as the maternal type. And she’s quite paranoid about needles and childbirth.’

‘Well, who can blame her? My mother had six, and it was no picnic.’

‘Six? Are you serious? Such a large family. Where are you in the pecking order?’

‘Third daughter. Says a lot about my character. My parents were desperate for a boy. He came after me. Spoilt rotten, as you can imagine. But don’t get me wrong, I love being part of a big family. You learn from a very early age that life is basically unfair. You also learn not to take yourself too seriously. How about you?’

‘I’m an only child.’

‘Ah.’

‘And by the way, Lisa, you were right about the lesbian lovers. The school is facing a law suit.’

He paused, and then said, ‘By the way, I’ve been sent a couple of free tickets for a play over in Manchester. You know my wife lives down south. Would you fancy coming? Sounds a bit experimental, but that might be your kind of thing.’

‘Why not?’ she replied.

It was only when they were halfway to Manchester, Edward driving his black BMW very distractedly, that he mentioned that the show in question was a production of Richard III. She knew that he loved Shakespeare, and so did she, so this was no surprise. ‘Apparently it’s got wolf and boar masks, and dancing, movement, physical theatre stuff – probably more your vibe than mine,’ he said, then he paused. ‘And it’s in Romanian.’

Silence. ‘I’m not sure whether there are surtitles.’

* * *

She loved the show. And she loved that he loved it. On the surface, he was so English, so Oxford, potentially a right stuffed shirt, but underneath, he was mischievous, a bit radical, full of surprises. Ever so slightly dangerous. Afterwards he offered her a drink in his flat.

She had parked her precious Mini at the school, and she didn’t want to leave it there overnight – the radio would be sure to be nicked. ‘Can we swing by the school, and I’ll follow you in my car?’

Later, and for many years later, he would tell her how he had looked into his rear mirror only to glimpse her terrified eyes.

She was terrified, because she knew that she was going to kiss him. He put on Tristan und Isolde (corny, but effective, she thought). He lit a fire, and they talked. As she was leaving, he took her in his arms. She felt less guilty for that long, passionate kiss than she had for tenderly kissing Jordan.

CHAPTER 4

The Truth Will Set You Free

Lisa knew that she would bear Edward’s children. And she knew that he knew it too. Parting with Pete was painful but necessary. Once she had slept with Edward, she knew that she could never sleep with her husband again. Strangely, she felt that to sleep with her husband would be a betrayal of Edward.

Moira was furious, chilly, vengeful. She threatened to ruin Ed’s reputation in and around his old school in the south. It was she who had raised him from the gutter, supported him whilst he rose in his career, put her own career on hold. She stormed over to Liverpool to have it out with him, taking her beloved cat and some empty suitcases. Edward was on the phone when she arrived. He hastily hung up.

‘Hello Tabitha, and where’s your mistress?’

‘She’s here, and don’t let me prevent you from chatting to yours.’

Ouch. She could be cutting, Moira, but she was also terribly witty. When she realized that he had made up his mind to leave, she told him that she would destroy him and take every penny. She told him that he and Lisa wouldn’t last five minutes, that he was making a big mistake. Then she proposed an open marriage. Half-ironically, half-seriously, Edward put the proposition to Lisa: ‘Gosh, that’s too sophisticated for me,’ she replied. ‘I’m a simple, northern, working-class girl, we’re all or nothing up here, I’m afraid.’

Moira begged him to go into marriage therapy. Then she tugged at his heartstrings, saying that she now wanted children.

He would give her the therapy. But he was cruel when he told her that even if he only lasted three months with Lisa, he would still want those months. The marriage was over. He loved Liverpool. He wanted to stay. He didn’t want to return to that tiny house in boring Guildford.

Lisa was angry when she heard that he was going into marriage therapy. She felt it was a mistake, and cruel to Moira, when Edward had no intention of saving the marriage. But he was adamant. He owed it to Moira and the seven happy years they had spent together.

Then one night Edward phoned from Guildford. ‘Darling, you will never believe what I have to tell you. Moira’s admitted in our therapy session that she’s been having an affair with one of my colleagues from the history department at my old school. I feel fantastic. Liberated. I no longer have to feel so guilty.’

‘Why did she tell you, Edward? Did she want you to know that she was desirable and sexy in the eyes of other men? Was it a last-ditch gamble to save the marriage, to show another, dangerous, side that you didn’t know existed? What’s her agenda?’

‘She said something rather noble. She said, “The truth will set you free”.’

* * *

Lisa married Edward. He’d first proposed in the Puck Building in Manhattan on New Year’s Eve at midnight, where he’d flown her for an old Oxford friend’s wedding to some hedge fund manager. They were dancing together to the sounds of an all-girls jazz band. She turned down his first proposal. ‘Edward, we’re both still married to other people. It’s too soon to think about another engagement.’

He tried again, this time in Paris, after they had both got the decree absolute. He gave her a box containing a beautiful gold lamé Vivienne Westwood dress, wrapped more exquisitely than any present she had ever received. Then he told her that he was taking her to a train station café for supper. When she got there, she saw that it was the fabulous art deco restaurant at the Gare de Lyon, Le Train Bleu.

Edward told her that this was the restaurant where Coco Chanel would have dined, and Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and then they would have caught the famous Blue Train to the French Riviera, and that was the kind of life he wanted with her. When he took out a small blue box, she grinned. It was a beautiful ring, in a style called Moi et Toi, which he had bought from Cartier. Two stones, a diamond and a sapphire, twisted around one another.

‘So is this a Yes, this time?’

‘OK then, Edward. Let’s do it. But it must be a small and intimate wedding. No family. No fuss.’

So they married. Edward in a cream linen suit, Lisa wearing a simple, elegant second-hand Chanel dress, made of cream tweed and bought at a bargain price from a student friend who had started an online store buying and selling vintage couture. It was cut on the bias, and fell to just below her knees, nipped in at the waist. It showed her figure to perfection. Her measurements were exactly the same as Marilyn Monroe’s (as she often reminded Edward, and anyone else who would listen). 36, 24, 34. The dress hugged her perfect breasts, and accentuated her tiny waist. She carried a handmade posy of white roses. She looked sensational. They told nobody that they were getting married, other than Chuck and Milly, who were the witnesses.