Полная версия:

A Life Less Throwaway

So, when your grandad says that people were nicer in the ‘good old days’, in this aspect, it’s true. Our materialistic tendencies have increased so much in the last few decades that our sense of community, our trust in others and our ability to be happy have been gravely reduced.

WHY IS THIS IMPORTANT NOW?

I’m not going to spend too much time pressing this point, because I think we all know that mindless consumerism is pushing our poor planet to a crisis point. We need to save it, and dropping the ball isn’t really an option. We live on the ball, and we don’t have another one to move to.

But it isn’t just the planet that should concern us. The trend towards materialism is also increasingly taking its toll on our day-to-day lives because it tricks us into losing the personal connections that make us happy.

A study of 2,500 consumers over six years concluded that no matter how much money you had to spend, materialism was linked to an increase in loneliness and loneliness in turn increased materialism.4 In the Seventies and Eighties, only 11–20 per cent of Americans reported that they often felt lonely; in 2010 that figure rose to between 40 and 45 per cent.5 The Mental Health Foundation in the UK also reported in 2010 that 46 per cent of us felt that society was getting lonelier.6

Relying on social media for connection is like trying to live off multivitamins – they might be a nice add-on, but they don’t feed us in the way we need. Research has shown that increasing your friends on Facebook has no effect on your well-being at all, but increasing your ‘real world’ friends from ten to twenty people results in a significant life-altering improvement – the equivalent of a 50 per cent pay rise.7

How does materialism make us lonelier? The messages we see in ads and social media channels perpetuate a myth that having things or looking a certain way makes us worthy of love and admiration. It’s very natural to want to feel special and appreciated, so we start to focus on our looks and achievements and buy high-status items that others will admire. However, any admiration or connection we gain is on a shallow level, and because it isn’t based on anything authentic, it leaves us feeling disconnected and unsatisfied. So we try even harder to get the love we need by showing the world our possessions, our status and our achievements, never guessing that the constant focus on the self means that the connection to others isn’t going to happen.

Sadly, materialism and narcissism are on the rise. A study published in 2012 tracked the values of graduates since 1966 and found that the importance given to status, money and narcissistic life goals like ‘being famous’ had risen significantly, whereas the importance given to finding meaning and purpose in life and a desire to help others had fallen.8 In addition, a study of students over the last thirty years has found that college kids today are about 40 per cent lower in empathy than the students of twenty or thirty years ago.9

We have become ‘all about me’ rather than ‘all about we’. The irony is that self-focused people hurt themselves more than anyone else. I don’t feel that it is a coincidence that the use of antidepressants has gone up 400 per cent in the USA10 and doubled in Britain in the last decade.11

To add insult to injury, marketers know how much we crave the connections that are the cornerstone of our happiness, so their adverts are full of family bonding and friends having great times – all to sell us goods that in reality are driving us apart.

IS OUR STUFF GETTING IN THE WAY OF WHAT’S IMPORTANT?

In March 2010, a group of five Pacific Islanders who had lived all their lives with practically no possessions were flown to the UK to be part of a TV programme where they looked at British life.12 As they walked around their hosts’ houses and explored London, they were surprised by all the ‘useless extra things’ they saw, saddened that busy commuters wouldn’t stop and talk to them, and shocked at seeing homeless people. This would ‘never be allowed to happen’ in their community.

The tribesmen’s simple lives meant that they hadn’t lost sight of what was important: love, respect and enjoying each other’s company. When they first arrived, they were all given their own room in their host’s big house. Later, when they stayed at a more modest place and all four of them were put together in a small bedroom, they declared themselves happier because now they were ‘able to talk to each other’.

It’s easy to romanticise the ‘noble savage’ life. There are of course many downsides, including lack of healthcare, gender equality and Ben & Jerry’s. But it is interesting to explore how our own society’s values might change if materialism was reduced.

In 2016, my fiancé, Howard, and I were invited to be on a TV show running an experiment to try and discover this very thing. The idea was that all our possessions, including our clothes, would be taken away from us.

‘No bloody way,’ Howard said before I was halfway through explaining the idea. Howard is not a naked person. Not ever. Not even with himself. So Life Stripped Bare went on to be made without us.13

Six people were stripped bare. Literally. Crouching-beneath-your-window-sill-so-the-neighbours-don’t-see-your-dangly-bits bare. All their stuff was locked away and each day they were able to choose one possession that they most wanted to have back in in their lives. Then (to get as much flesh wobbling as possible), they had to run half a mile up the road to a shed to get it back.

One of the volunteers, Heidi, a 29-year-old pink-haired fashion designer with thirty-one bikinis, sobbed as the removal vans arrived in her trendy area of London. ‘I feel my stuff defines me,’ she said. ‘I want people to like me, think I’m cool, think I’m nice, and if I don’t have my hipster coat, if I don’t have my nails painted or my rings on, I don’t think they will like me …’

On Day 2, after a gruelling night on the floor, she reflected, ‘Yesterday I was crying because I wanted everything. Today I just want my mattress.’

In fact she got more than that. Out on the street, two passing girls stopped to help her carry the mattress back to her house and they bonded over the funny situation.

Almost in tears, Heidi said to camera, ‘Now I’ve got some friends, I honestly feel I’ve got everything … When you have nothing, people make the whole world of difference.’

I’d like to turn this on its head and say, ‘When you’ve got people, there’s nothing much else you need in the world.’

All the participants of Life Stripped Bare found that once their basic comfort levels were met, they became less and less bothered about picking up new items from the shed. We can be happy with very little, yet due to materialism, the average home has 300,000 items in it …

So how can we reverse this trend? Let’s start with some exercises to break free of materialism.

exercise

PERSUADE YOURSELF OF THE IMPORTANCE OF NON-MATERIAL ACTIONS

You may think you don’t need persuading that there’s more to life than materialism, especially after reading this chapter, but write an e-mail to yourself about it anyway. This may seem a bit twee, but has been proven by professor and clinical psychologist Natasha Lekes to have a tangible impact on your happiness.14 I’ll even start you off:

Dear me,

This feels odd, but I’m going to tell you about why I think having good relationships, helping the world to be a better place and growing as a person are so important …

exercise

SIGN UP FOR BUYMEONCE MANTRAS

Sign yourself up for free daily mantras at BuyMeOnce.com. These short phrases will help your subconscious make good choices for you and you’ll be less swayed by materialistic messaging. Here are three to get you going:

• ‘I am good enough.’

• ‘I have everything I need to be happy.’

• ‘I am grateful for all I have.’

exercise

SIMPLE WAYS TO COMBAT MATERIALISM EVERY DAY

• Remind yourself on waking that this life is amazing but also short – smile and say thank you for the day.

• Find time each day to focus on your own personal growth and self-worth. (You’ll find ideas in this book.)

• Find people who share your passions and build a sense of community with them.

• Block materialistic messages as much as possible (more on this later).

• Practise meditation and mindfulness – there’s a wealth of material out there to get you started.

• Feeling close to nature has been shown to decrease materialism, so get out as much as possible, even if you just go into your back garden or a public park. Nature documentaries can also be a lovely way to escape from seeing ‘stuff’.

2

Planned Obsolescence

or

Why they don’t make ’em like they used to

‘Obsolescence’ is a horrible mouthful of a word that essentially means ‘when something becomes useless’. ‘Planned obsolescence’, therefore, is when people plan for products to become useless. Deliberately. Let that sink in for a second.

There are two main ways planned obsolescence happens. The first is physical, where companies design products to break before they need to. That is the subject of this chapter. The other is psychological obsolescence, where people are made to feel that they no longer want the possessions they already have. We’ll look at that in the next chapter.

But first I’m going to take you back to the Twenties and Thirties to discover how planned obsolescence came about. I’ll also share with you some of the shocking evidence of companies who have conspired against us to change the way we buy forever.

WHO PLANNED IT?

Planned obsolescence was born and brought up (to be very naughty) in America. ‘Obsolescence is the American way,’ boasted industrial designers Roy Sheldon and Egmont Arens in their 1932 book Consumer Engineering. And certainly Americans took quickly to the idea of rampantly replacing their possessions, while Europeans still held on to theirs as long as possible. Some people at the time did raise concerns about the extra waste and damage to the environment, but their concerns were quickly brushed under the cheap new rugs that were being made. Sheldon and Arens justified their championing of obsolescence by pointing out that while Europe had used up many of its natural resources, ‘in America, we still have tree covered slopes to deforest and subterranean lakes of oil to tap …’1

America also had a problem with overproduction. By the early Thirties, the States had got very good at making lots of things very quickly, but wasn’t too good at selling them. The stock market had crashed and the country was in the middle of what became known as the Great Depression, with millions jobless and around half of all children without decent shelter or food to eat. In these conditions we can’t blame people for clutching at ideas like planned obsolescence to solve the issues, even if we are now left to deal with the fallout.

In 1932 a Russian-American called Bernard London published a grand plan entitled ‘Ending the Depression Through Planned Obsolescence’. After noticing that people held onto their products longer in a depression and this meant less money being spent on goods, he suggested that every product, from shoes to cars, houses to hats, be given a set lifespan. Once that lifespan was up, the items would be legally ‘dead’ and people would have to turn them in to the government to be destroyed or risk a fine. They would then of course have to buy them again new.

Mr London sold his idea as the saving grace of the US economy. ‘Miracles do happen,’ he said. ‘But they must be planned in order to occur.’2

This particular miracle never came off. Maybe because the government realised that forcing people to hand over their possessions for incineration was a sure-fire way to get unelected.

What ended up happening was stealthier. Businessmen, politicians, manufacturers and the advertising industry colluded to change both products and minds, with the aim of turning citizens into consumers. In fact they had been colluding already.

The lightbulb conspiracy

It’s very hard to find a smoking gun when you go looking for evidence of people deliberately building things to break. Unsurprisingly, this is not something that companies will admit to doing if you call up their head office. The most famous proven case was the subject of a truly shocking documentary called The Light Bulb Conspiracy.3 It’s famous because it’s one of the few times we’ve found actual written proof that this shady practice takes place.

By 1924, lightbulbs had been getting better in quality for some time; some were now lasting up to 2,500 hours. Then representatives of the biggest electric companies in the world, including Osram, Philips and General Electric, met in Geneva on the night before Christmas to hatch a very unChristmassy plan.

By the end of the meeting in a cramped back room, they had formed a secret group known as the Phoebus Cartel, and had all agreed to send their bulbs to Switzerland regularly to be tested to ensure they broke within 1,000 hours. They had even agreed to be fined for every hour they went over the limit.

What they were doing was on very dodgy legal ground and we know that not everyone was completely happy about it. Some engineers attempted to get around the 1,000-hour limit by designing bulbs of a higher voltage, but they were soon found out and scolded by the head of Philips:

‘[This bulb design] is a very dangerous practice and is having a most detrimental influence on the total turnover of the Phoebus Parties … After the very strenuous efforts we made to emerge from a period of long-life lamps, it is of the greatest importance that we do not sink back into the same mire by supplying lamps that will have a very prolonged life.’4

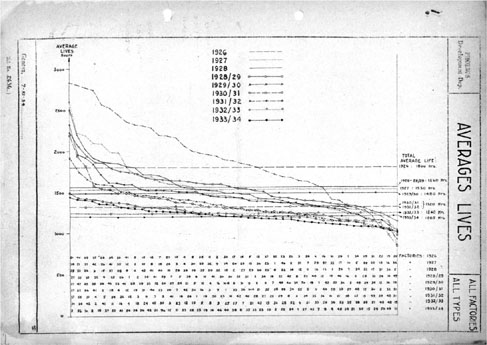

They did not sink back into the ‘mire’. If you look at the graph below, showing how long bulbs last, you’ll see that there’s a steady decline until the cartel reached their goal and the average bulb expectancy ground out at around 1,025 hours.

Photo: Landesarchiv Berlin

How did they get away with it? Many of the changes were sold to consumers as efficiencies and improvements in brightness. And despite lasting less than half as long as the older lightbulbs, the new ones were often even more expensive.

The companies profited enormously from their tactics; one reported that their sales had increased fivefold since they’d changed their designs to be more delicate.

The cartel was disbanded during the Second World War, when it became a little awkward for German, British and American businessmen to get together. But the damage had been done; the life expectancy of bulbs didn’t recover.

I recently had the pleasure of talking to several people who work in the lightbulb industry today. When I shared the story of the 1924 Phoebus Cartel, they said that in many ways things were no better now.

One engineer told me that one of the most underhanded tactics she’d witnessed recently was bulbs being sold with an advertised life of seven years but purposefully designed so they would only last two or three years, just long enough to avoid customer complaints and returns. And this company was a major player in the lightbulb world.

‘They’re lying to us,’ she said bluntly. ‘The lightbulb industry is full of misinformation. I’ve run independent tests on bulbs and some of them are running so hot there’s no way the components inside them will survive the time the packaging says they will.

‘There are all sorts of cheats going on. For example, “15,000-hour lifetime” might be written in large print on the front of the box, while “one-year guarantee” might be written in small print on the back. And then you get guarantees that are only valid if the bulb is used for one to two hours per day.’

This misinformation has sadly stopped genuinely good bulbs from succeeding, as customers can’t see the difference.

One scene from The Light Bulb Conspiracy which filled me with dread was footage of a teacher in a design college handing out various products to his students and asking them how long they thought they were designed to last. ‘It’s important for you to know,’ he said, ‘because you’ll have to design to a certain lifespan and to the business model the company wants.’ This is particularly disheartening, as he’s teaching the next generation of designers not to make the best products they can, but ones that last as long as they need to for the company to sell them.

Beyond bulbs

By the Fifties, obsolescence was fully grown and had left home to travel the world. Now its influence can be seen everywhere, from the furniture left outside to be picked up in Europe to the mountains of electrical waste in Asia.

In the Seventies, Eighties and Nineties voices did start being raised about the need for products to last longer to avoid an environmental crisis, but governments and businesses chose instead to concentrate their efforts on recycling.

Recycling is a positive thing and certainly takes away the guilt we feel about discarding something. But the truth is the environmental difference between being able to carry on using something and recycling it is colossal. Recycling still takes energy, waste collection and processing, and usually manufacturing a new object to replace the one we are discarding. This suits companies very well, but we and our planet end up paying the price.

So here we are. The calls for longer-lasting products have been ignored for decades, planned obsolescence reigns supreme and the commercial world is steaming us blindfold into an iceberg of trash.

QUALITY STRIPPING

We’ve all experienced quality stripping, and I’m not talking about particularly adept G-string jiggling. If ‘building it to break’ is the famous poster child of planned obsolescence, ‘quality stripping’ is probably the most common tactic used. It’s being done to products all over the world, all of the time, and it’s not even being denied, it’s just being explained away.

In the spring of 2017, I was invited to the wilds of Yorkshire to visit Morphy Richards, a prominent British home appliances firm. I was thrilled that they were open to talking about longevity, as every other company I’d spoken to was quick to be defensive about the issue. I took the opportunity to question them about why things didn’t last as long as they used to.

‘I’ve been told by an engineer friend,’ I said, ‘that it isn’t necessarily that things are built to break, but that every year you might be asked to take more costs out of the product, so the materials get thinner and cheaper and the quality starts to come down. Is this true?’

‘That’s exactly it,’ they agreed. ‘It’s all about cost. With enough money, we can make you something that lasts as long as you want, but we have to hit a certain price to please the marketers and retailers.’

This all sounds quite reasonable, but the effect of it is not. There is solid evidence that appliances are breaking earlier and earlier. In fact, the number of appliances that must be replaced because of breakage has doubled since 2004. Most shockingly, boilers used to last a wonderful 23 years in 1980, but are only expected to last 12 years by 2020.5

There is also a heartbreaking disconnect between the people who design and make the products and the people who make the decisions to forego quality. Engineers are craftsman and generally want to make the highest-quality products they can. But many businesspeople see manufacturing companies purely as money-making projects. Whether they make hairdryers or hamburgers makes no difference to them.

The cost-cutting decisions might not even be made by the company that makes the product but by an “umbrella” company which owns a lot of brands. That company may be so far away from the making of the actual product, they may not even know what it looks like. But they can still demand that the engineers find a way to make it 10 per cent cheaper than they did the year before. You can’t do this for long before the lifespan of the product is affected.

‘Companies have become increasingly short term in their thinking,’ admitted Thor Johnsen, who has been in the business of buying, selling and managing other companies for many years. ‘They’re greedy for a quick buck, and short-term greed produces massive problems. Companies will put nearly all their money into their branding and marketing, spend a bit on design and then build their products as cheaply as possible. That’s the model now.’

‘Why are they getting away with it?’ I asked.

‘The trouble is,’ he said, ‘shoppers might say they want quality when we ask them, but when we watch them, they don’t actually buy for quality. They buy for convenience or price.’

‘Do you think part of the trouble,’ I suggested, ‘is that people go into a shop and see a row of products and can only guess which one lasts the longest? So they end up going for what’s cheapest or what goes best with their kitchen.’

‘Yeah, that might be it,’ he said. ‘Branding used to help us know which was the best quality. But that’s just not the case anymore.’

So far, so depressing. And this isn’t the end of the bad news. Have you ever noticed that sometimes online reviews look as though people are talking about entirely different-quality products, even while reviewing supposedly the same item? Of course different people have different expectations, but several engineers have told me that with so many products being made overseas, there is a temptation for factories to secretly change the quality of the products after the first couple of batches. The factories win the business by making something great, but then start cutting corners. Or everything but the corners. Unless these products are then tested, they make it into the shops and quickly into landfill.

This isn’t only annoying and wasteful, but also sometimes incredibly dangerous. Tyres might be made with cheaper-quality rubber which explodes at high speeds, or the paint used on toys might be switched for a cheaper toxic lead variety.

One of the most shocking findings was that a shipment of aluminium construction materials, crucial to holding up a building, was found to have decreased in weight to under 90 per cent. All of the profits from that saved aluminium would have gone to the factory owner. All of the responsibility for the danger and the cost of recalls would have gone to the company that sold it. It’s almost impossible to sue a Chinese factory, and because companies like to keep their suppliers secret, the factories don’t have to worry too much about damaging their reputation.6

The British appliance company I visited is very aware of these problems, so anything that comes in from overseas is tested by them in their own lab.

‘Nothing comes out of here alive,’ said the head of the lab gleefully as he showed me around. Kettles were boiled, poured, filled and boiled again, boiled dry and abused with mechanical arms. Toasters were tortured – popped and popped and popped again until they broke. Irons were slid over miles and miles of rough denim to ensure that their plates could take the strain of years of use.

‘The factories in China know we do this,’ I was told, ‘so they know they can’t get away with sending over inferior products. If it fails here, it doesn’t go to market.’

Most companies can’t afford their own testing facility, however, so we’re often left at the mercy of unscrupulous manufacturers, some of whom are happy to take our money and give us poison and trash in exchange.

If you’re reading this and thinking it’s as depressing as an empty toilet-roll holder, I apologise. It is depressing, but it’s also important to know what we’re up against, so we can know how to combat it. There’s a section at the end of this chapter on how to do just that.