Полная версия:

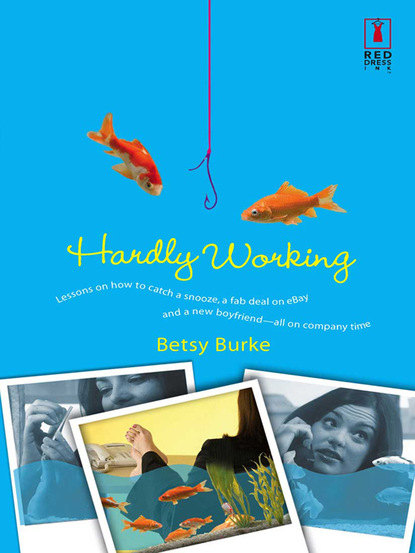

Hardly Working

Some ex-boyfriend from my past?

Or Mike—my ex-true love?

Or an ex-boyfriend-to-be from my future? Some guy I’d met at a fund-raiser then forgotten about, who might be a friend of a friend of a friend and had gone to a lot of trouble to get my number?

Or Thomas? My therapist? For all the money I was paying him, he was supposed to be making me feel better, wasn’t he? And a little birthday call would make me feel better.

And then I remembered.

The Tsadziki Pervert.

He’d been phoning me up and, in an eerie hissing voice, proposing to cover my whole body in tsadziki. You know that Greek dip made of yogurt and cucumbers? Then he was going to scoop it all up with pita bread until my skin showed through. It had to be some guy who had seen me around. Probably with Mediterranean looks and visible panty line, knowing my luck. He knew who I was because he was able to describe some of my physical features. If it was him again, this would be his third and last call.

I skidded into the hallway and found the shiny silver whistle, the kind that crazed PE teachers use. It was supposed to be dangling from a string next to the phone for any kind of Telephone Pervert Emergency that might come up, but I’d forgotten to do it. I’d made a mental note to avoid all of Vancouver’s tavernas and Greek restaurants but I’d forgotten to tie on the secret weapon. I held the whistle near my lips and got ready to pierce the Pervert’s eardrum.

I know what you’re thinking. Why didn’t I have a call-checking phone or an answering machine? And you’re right. I should have. But that would have taken such a big chunk of mystery out of my life. Not knowing who was on the other end, and anticipating something good, or something evil involving sloppy exotic foods, burned up at least fifty stress calories. And there was always that got-to-have Gap shirt to spend the money on instead.

My buttery hand grappled with the receiver. “Hello?”

“Happy birthday, Di Di.”

“Mom.” I was relieved and let down at the same time. If my own mother hadn’t called, it would have meant that things were grimmer than I thought. “I didn’t expect to hear from you. Aren’t you supposed to be out in the field up there in the Charlottes?”

“Cancelled that, poppy. Off to Alaska in a couple of days. They want me to go up and take a look at the Stellar’s sea lion situation there. Been following a project on dispersal and we’ve got quite a few rather far from natal rookeries. Shouldn’t you be celebrating with friends, Di Di?”

“I am.” I turned The X-Files up higher.

“Sound a little odd. Not on drugs, are they? By the way, a couple of things. Now…what would you like for your birthday? I think it should be something very special. Thirty. You’re on your way to becoming a mature person.”

As if I needed to be reminded.

“I’ll give it some thought, Mom.”

“Righto, Di Di. We’ll be seeing each other soon anyway. I’ll be popping in and out of Vancouver. Have several guest lectures to give up at the university. Migration of the orcinus orca is first on the schedule. They’ve organized an entire cetacea series this year. I told them I was quite happy to do the odd one as it would give me a chance to see my daughter. Oh, and another thing I keep forgetting to mention. Mike and his little wife came around several weeks ago.”

“His little WHAT?”

“Tiny limp thing, Dinah dear. Believe they’ve been married for about three months. I should think she might just blow away with the first strong wind. Don’t think she’ll be helping old Mike much with the hauling.”

“What hauling?”

“She and Mike were just about to move to Vancouver when I talked to them. I gave them your address and phone number. He seemed very eager to see you again.”

I could feel the popcorn backing up into my throat.

I liked to blame my mother for the fact that I was cruising into the end of my thirtieth birthday and flying solo. And even if it wasn’t her fault, I needed to blame my manlessness on someone. She was the logical choice.

I’d often whined to Thomas, my therapist, “How am I supposed to deal with a proper relationship? I’ve had no role models. My mother thinks that men are beasts of burden who are useful for mending your fences, mucking out your stables, feeding your seals and whales, and worshipping at your feet, but should definitely be fired if they can’t be made to heel.”

My mother is a zoologist. Marine mammals are her specialty.

And Thomas would reply, “No life is accompanied by a blueprint.”

As for a father, well, that was the main reason I was paying Thomas. There was just a terrible lonely rejected feeling where a flesh-and-blood father should have been.

Thomas was very attractive. I’d shopped around to find him. I went to him twice a month. He wasn’t your full-fledged Freudian—I couldn’t have afforded that. He was a bargain-basement therapist with just the right amount of salt-and-pepper beard and elbow patch on corduroy. He cost about as much as a meal at a decent restaurant but wasn’t nearly so fattening. His silences were filled with wisdom. And he had a real leather couch. This probably worried his girlfriend upstairs. I could picture her creeping around, but then having to give in to her suspicions and stick her ear to the central heating grates, just to be sure that nobody was pushing the therapeutic envelope down in the basement studio.

I talked and Thomas listened wisely. Then he’d pull on his pipe, expel a plume of smoke, and sprinkle his opinions, suggestions and bromides over me.

All through my childhood, I’d fantasized about this father of mine. When I was six, and asked my mother who my father was, she gazed coldly and directly at me and explained that he was out of her life, and therefore out of mine, and that I was not to ask about him again.

My mother is tall, lean, white-skinned, rosy-cheeked and blond with the beginnings of gray. She looks like a Celtic princess and is considered beautiful by almost every man she meets. I’m medium height, black-eyed, dark-haired, and on the good side of chubby. Genetically speaking, I had to wonder if that made my father a short, dark stranger.

My mother had been orphaned young, and my great-grandparents, whom I vaguely remember as a couple of gnarled, complaining, whisky-drinking bridge players, had left her a trust fund. My mother is the triumphant product of an elite private school in Victoria where she and other rich girls bashed each other’s shins with grass hockey sticks and studied harder than the rest of the city. There, she acquired her slightly English accent and a heartiness that plagued me all through my childhood. There was no ailment that chopping wood, cleaning fish or a good hike along the West Coast Trail couldn’t cure. I was fit against my will.

From the day I hit puberty, I couldn’t wait to get somewhere where the fish, feed, and manure smell didn’t linger on my clothes.

I’m convinced that if my mother had grown up without a trust fund, and had been forced to have a man support her through a pregnancy, things would have been different. I would be a well-adjusted girl with a steady permanent boyfriend. Studying marine mammals is not exactly a lucrative profession. Only somebody with an independent income could carry out the kind of field work or maintain the kind of hobby menagerie my mother had over on Vancouver Island. The animals; the seals, raccoons, hawks, dogs, cats, sheep and ponies required extra hands and lots of feed.

When I was little, I was convinced that I too was a member of the animal kingdom and that all those pets were my brothers and sisters. To get my mother’s attention, I would get down on all fours and eat out of the dog’s dish. My mother didn’t even blink. Maybe I really was just another vertebrate in all her animalia, an experiment, a scientific accident. But whenever I brought this up with Thomas, he’d tell me that I probably wasn’t seeing the whole picture. Maybe he was right. And maybe not.

I knew what I wanted for my thirtieth birthday.

At twenty-five minutes to midnight, there was a knocking at my door. When I opened up, Joey barged past me brandishing a bottle of Asti Spumante. Cleo followed, holding a bottle of chardonnay. Both of them looked as though they’d run a marathon.

I followed them both to the living room, then Joey did an about-face, said, “Glasses,” and went straight back into the kitchen to look for some.

Cleo flapped her long burgundy fingernails at me. “I know, Dinah, I know, we’re so late and you’re going to kill us.”

“I don’t turn into a pumpkin until midnight,” I said. “That gives us twenty-two minutes to get toxic and sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to me. How was the conference?”

“Shitty, Dinah.”

“Really?”

“No, literally. It was all about what we’re going to do or not going to do with the planet’s crap. Excrement. I feel like I need a bath. You know who the biggest culprits are?”

I shook my head.

“Cattle. The methane emissions from all the cow flop on this planet are going to blow us from here to kingdom come.”

“Imagine it, Dinah,” shouted Joey from the kitchen, “all the way home in the car, I get to listen to a lecture about cow farts.”

“It must have been a gas,” I said.

“Har, har,” he bellowed. I could hear him crashing around in my kitchen cupboards. “Dinah. You’ve got no glasses. Where are all your Waterford crystal wineglasses?”

“They were Wal-Mart, not Waterford and they got broken,” I said.

It was a little embarrassing.

“All of them? Should I guess? Accidentally on purpose?” asked Joey.

“Thomas said it was okay to break things as long as nobody got hurt. Mike bought them years ago and I finally got around to breaking every last one. It felt great.”

“Okey-dokey. We’ll drink out of the Nutella jars. Who wants Minnie Mouse and who wants Donald Duck? I get Dumbo.”

We poured the drinks and toasted my thirtieth.

Cleo sauntered over to my west-facing side window and gazed out. “Ooo. Your neighbor’s awake. Very, very awake.”

I panicked. “Close the curtains, Cleo. If you’re going to be a peeping Tom, try to be subtle about it.”

She whipped the curtains back across the glass and continued to spy through the crack in the middle. “God, what’s that he’s got with him? A black cat? Ooo. Hey. He’s taking off his shirt. Look at that bod. Fantastic. So toned. That man is so buff. This is better than Survivor. Take off the rest of it, honey, we’re waiting.” Cleo’s hot breath steamed up the window glass.

Joey raced over to the window and tried to elbow Cleo out of the way. “Shove over. Let me see.”

“You gu-uuys,” I protested.

Cleo’s face was flushed. “I don’t see how you can stay away from this window, Dinah? Does he always leave his blinds open? He is one hot hunk of man.”

“How would I know? He just moved in. And I try not to spend all my time glued to the window spying on my neighbors.”

It was a lie.

The new neighbor had moved in that summer. From the side window in my living room, I could look straight down into my neighbor’s ground-floor living room. His was a nineties house with floor-to-ceiling sliding doors that filled the lower north and east side of the house. A tiny L-shaped patio had been created outside the sliding doors, and beyond that, a row of bamboo had been planted to shield the windows from the street. Except that from my second-story side window, I could see everything. It was like looking into a fishbowl, perfectly situated for anonymous viewing of his living room as long as I kept the lights turned off and the curtains closed. It was an exercise in futility though because my neighbor was gay.

The neighbor’s partner would show up sporadically, sometimes for the weekend, sometimes for a couple of days during midweek, and there would be small moments, never anything overt, but a hand on a hand, an occasional woeful hug, long intense talks in the living room, wild uncontrolled laughter bubbling up, the both of them so easy with each other, so completely relaxed, that there was no doubting how well matched they were. They were perfect soul mates. I envied and admired them. From my window, their relationship appeared to have everything. Then the partner, who was small and dark in contrast to my heavier brown-haired neighbor, would disappear for a week or more, and my neighbor, obviously at a loss, would pull out his home gym and work out.

During those hot evenings in late August, I was behind that curtain watching him move his half-naked sweat-shined body. And I swear, if Russell Crowe had come along and hip-checked my neighbor out of the way, and taken his place there at the bench press, and let the last shafts of light catch the muscular ripple of his arms and torso, you wouldn’t have been able to tell the difference between the two of them.

August flowed into September and September into October and I still went to the window to catch a glimpse from time to time. My voyeurism told me that I’d been hanging on too long. How could I criticize the Tsadziki Pervert when I too was becoming an urban weirdo? I told myself that it was because I needed time before getting burned again. But now the years were beginning to speed up. I’d reached thirty without even realizing it.

“You can get your mind off his éclair, Cleo. It’s not earmarked for you. Take my word for it,” said Joey, “Dinah and I have been surveying him for a while and we are happy to inform you that he is of the religion Pas de Femme. Where information gathering is concerned, we make the CIA look like a bunch of wussies.” Joey’s expression was triumphant.

“He’s not gay,” wailed Cleo. “He can’t be, can’t be, can’t be.”

“He is, he is, he is,” said Joey, stamping his foot in imitation.

She clumped over to the table to pour herself another larger slug of wine. “The best ones. Always the best ones. And anyway, Joey, how do you know?”

Joey said, “I’ve seen him around. In the clubs.”

“Which clubs?”

“Well. I’ve seen him at Luce and Numbers and Lotus Sound Lounge. And he always has his arm around the same guy. The guy that comes over sometimes. Small, dark French-looking man with zero pecs. I’m telling you, he’s so monogamous he’s dreary.”

I took one last peep. The neighbor stood motionless now, looking out at the sky and the luminous gray clouds that threatened to burst. It was odd that we’d never met, never crossed paths. Just bad timing, I supposed. He only lived next door, but his world and mine could have been a million light years apart.

“Oh shit,” said Joey, “he’s turned the light off.”

“Probably tired of his voyeur neighbors,” I said.

Cleo had turned away from the side window to face my big front French doors. She shrieked and pointed. Outside the windowpane, hanging in midair above the little balcony, dangling from a cord, was a shadowy man.

Chapter Two

The man-shaped silhouette waved.

I ran over and opened up the French doors, then stepped out on the balcony to help the guy down.

“Simon. You’re back. Come inside before somebody calls the police.”

With expert rock-climber’s maneuvers, Simon lowered himself down to the balcony, then began to haul his cords down after himself and wind them up. He was grinning the whole time. I stepped aside to let him into the apartment, then I picked up his equipment and passed it through to him. He stood in the middle of the living room, straightened up and brushed himself off. He was dressed in black, and very lithe, thinner than when I’d last seen him, two years before.

“Hey, Di. Happy birthday. Figured I’d drop in on you. Hey, so cool to see you.”

Joey muttered, “Now that’s what I call an entrance.”

I smiled at Cleo and Joey. “This is the Simon Larkin I’m always telling you about. The one I grew up with. The one who shared my dog biscuits.”

“Yeah,” said Simon. “You could say that Di’s my honorary sister.”

Joey batted his eyelids and leapt forward to offer his hand. “Hi, great to meet you, Simon. I’m the famous actor, Joey Sessna. You may have seen me in—”

I punched Joey’s upper arm.

He yowled. “Ouch. Jeez, Dinah. Wha’d you do that for?”

“Simon doesn’t know who you are, Joey. He doesn’t watch TV. He doesn’t have to. He has real-life entertainment. When he isn’t scaling some terrifying rock face, he’s infiltrating some interesting urban landmark. Right, Simon?”

“Hey, babe. That’s me.” He grabbed me and squeezed me in one of his death lock hugs. Cleo and Joey were practically drooling. Simon was tall and toned with messy strawberry-blond curls and navy-blue eyes. He looked like a Renaissance angel in Lululemon sportswear.

Cleo grabbed my glass out of my hand, poured some wine into it, and handed it to Simon. “I’m Cleo Jardine.”

He said, “Thanks, Beauty,” and downed it in one gulp.

Joey began to jabber at Simon and I started to whisper to Cleo, “Before you get any ideas, there’s something I’ve got to tell you about Simon….” But she and Joey were so involved in ogling him that they couldn’t hear me.

“Hey Di,” said Simon, “got any growlies in the house? I’m perishing with hunger.”

I knew what was in my fridge. The Empty Fridge Diet was the most successful one I’d tried so far. We quibbled for a few minutes, then decided to call out for Chinese food when Cleo offered to pay.

When the food arrived, we all attacked it like starving refugees. But after a minute or two, I noticed Cleo and Joey making way for Simon as he helped himself two and three and four times. Simon had that effect on people.

Joey’s chatter turned into a runaway train as he tried to impress Simon with his TV and movie credits. Simon just grinned and nodded but I doubted he knew what Joey was talking about.

I said quietly to Cleo, “Simon is a bottomless pit. You don’t ever want to invite him over for dinner.”

A sly look came over her face. “I was thinking I could take him to one of those all-you-can-eat smorgasbords.”

Finally, when all the little cardboard cartons were empty, Simon rubbed his stomach and beamed angelically. “That was a nice little snack. We can get a proper meal a little later, huh, Dinah? After we’ve been out for your surprise birthday treat.”

“A proper meal? What were we stuffing into our faces just now? And a surprise? It’s after midnight, Simon. I’ve got a big day at the office tomorrow. The CEO’s coming in from the national headquarters…”

“Dinah, I’m bitterly disappointed. When was midnight ever late for you? Better face it. You’re only thirty and you’re so far over the hill you might as well just lie down and roll the last little bit of the way into your grave.” He fatefully shook his head.

I took the bait. I leapt up and began to run around, clearing up, snatching glasses out of hands and throwing away balled-up paper napkins and empty takeout boxes. “Okay, so where are we going?”

“Like I said, it’s a surprise. And I should add that I actually put some research into this.” I was very familiar with Simon’s brand of surprise. I both dreaded and longed for it.

Cleo and Joey looked at each other, then at Simon and me, and said in chorus, like two schoolchildren, “Can we come, too?”

“You don’t know what you’re getting yourselves in for. This is my whale rub friend,” I said.

“Oh my God,” said Cleo melodramatically, “not your whale rub friend? Now would that have something to do with massage?”

“Whale rub?” chirped Joey. “It sounds obscene.”

“I’ll tell you about it sometime,” I said, “when I’m really, really drunk.”

Simon nodded and chuckled. “Yeah. I’d forgotten about the whale rub.”

“Please, Simon, can we come too, wherever it is you’re taking her?” schmoozed Cleo. “I hate to be left out of the party.”

“Can we, Simon, can we?” asked Joey.

Simon moved into his inimitable and rare business mode. “I don’t know. You’re going to have to be fast. Comfortable clothes. Dark stuff. No high-heeled shoes, eh, babe?” He directed this at Cleo. “No tail ends that could hang out or get caught in or on something. We should get going, Di. We’ve got a bit of a tight and squeaky time frame here.”

I said, “What he means, is that if we don’t have the timing perfect, we’ll be like mice in a trap, squeaking our heads off. Simon doesn’t have much respect for legalities.”

“Aw, c’mon now, Di. I’ve got a most excellent lawyer. So let’s breeze on outa here,” said Simon.

Joey went back to his place to change and I lent Cleo something in black. I had a closetful. Nothing hides the fat better than black. While we were getting ready, Simon was going through my kitchen cupboards. He managed to find an old bag of sultana raisins, some chocolate chips, half a box of muesli, and a joke tin of escargot that I’d won at a New Year’s raffle. He inhaled all my remaining food supplies and announced that it was time to leave.

Simon guided us up to the roof of the Hotel Vancouver in Mission Impossible style, dodging porters and chambermaids, coaxing us through poorly-lit, forlorn hotel arteries that gave off stale and slightly greasy-smelling odors, corridors and dark places that had a vague presence of skittering creatures nearby—rats, mice, pigeons. All the way up the endless flights of stairs, he whispered, “Don’t fall behind.”

I managed to keep up with Simon. Joey, who was skinny and hyperactive, was just behind me. I sprinted along but my legs felt it around the tenth floor. Cleo, who was only interested in physical activity if there was a man dangled like a carrot at the end of her efforts, lagged about a floor behind us all, complaining that she wished she’d made her last will and testament before we’d left. We went up and up and up until we reached a door. We followed Simon out into a long musty narrow corridor lined with tiny gabled windows that looked out onto the city, a zone where chambermaids must have slept once, country girls who cried into their pillows night after night until the city was finally able to distract them.

Once he had coaxed us all out onto the roof, Simon explained. “The idea behind a good urban infiltration is to take the road less traveled, find those forgotten back routes and rooms. For example, I’ve got a friend who did an infiltration in a part of the University of Toronto. He kind of lost his way and ended up taking a tunnel to another wing that had all these more or less abandoned barrels stored there. They were full of slime. No kidding. Later he found out the barrels were used to store eyeballs. Hundreds of thousands of eyeballs. Must have been part of the ophthalmology department. That’s the fun of it. Discovering things. He said it was a pretty freaky place. Could have been a hiding place for all kinds of crazies.”

We were seated precariously on the green copper roofing looking out over the myriad of city lights under the cloudy night sky. The gray stone of the hotel plunged downward just a few feet from where we sat. We could see between the glass high-rises to the North Shore and Grouse Mountain high up in the distance. Beyond the dense bright core of downtown in the other direction I could see the Burrard and Granville Bridges, the beads of car lights in constant motion.

Simon opened his small backpack and pulled out a bottle of Brut. “For you, Di. Happy birthday, eh?”

“Jeez, Simon, if somebody had told me that I was going to toast my thirtieth birthday on the rooftop of the Hotel Vancouver, quite a different picture would have come to mind.”

“It’s exciting,” shivered Cleo, paler and stiller than usual.

Joey nodded in agreement, looking no less terrified.

Simon could have been telling Cleo and Joey that the earth was flat and the moon was made of blue cheese and they would have had the same expressions on their faces. Simon was so decorative, so distractingly gorgeous. I should have, I really should have told them what else he was. And wasn’t.

“Fascinating,” oozed Cleo.

“Absolutely,” agreed Joey.

“Now I have something to say,” I announced.