Полная версия:

The Fontana History of Chemistry

The sixteenth century saw great improvements in chemical technology and the appearance of several printed books dealing with the subject. Such treatises mentioned very little chemical theory. They aimed not to advance knowledge, but to record a technological complex that, in Multhauf’s opinion, ‘although sophisticated, had been virtually static throughout the Christian era’. Generally speaking they discussed only apparatus and reagents, and provided recipes that used distillation methods. Many recipes, especially those for artists’ pigments and dyes, bear an astonishing resemblance to those found in the aurifictive papyri of the third century and therefore imply continuity in craftsmen’s recipes for making imitation jewellery, textile dyeing, inks, paints and cheap, but impressive, chemical ‘tricks’.

One such book was the Pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio (1480–1538), which was published in Italy in 1540. This gave a detailed survey of contemporary metallurgy, the manufacture of weapons and the use of water-power-driven machinery. For the first time there was an explicit stress upon the value of assaying as a guide to the scaling up of operations and the regular reporting of quantitative measurements in the various recipes. On alchemy, despite retaining the traditional view that metals grew inside the earth, Biringuccio provides a sceptical view based upon personal observation and experience6:

Now in having spoken and in speaking thus I have no thought of wishing to detract from or decrease the virtues of this art, if it has any, but I have only given my opinion, based on the facts of the matter. I could still discourse concerning the art of transmutation, or alchemy as it is called, yet neither through my own efforts nor those of others (although I have sought with great diligence) have I ever had the fortune to see anything worthy of being approved by good men, or that it was not necessary to abandon as imperfect for one cause or another even before it was half finished. For this reason I surely deserve to be excused, all the more because I know that I am drawn by more powerful reasons, or, perhaps by natural inclination, to follow the path of mining more willingly than alchemy, even though mining is a harder task, both physical and mental, is more expensive, and promises less at first sight and in words than does alchemy; and it has as its scope the observation of Nature’s powers rather than those of art – or indeed of seeing what really exists rather than what one thinks exists.

That is succinctly put: by the sixteenth century, the natural ores of metals, and their separations and transformations by heat, acids and distillations, had become more interesting and financially fruitful than time spent fruitlessly on speculative transmutations.

Alchemy had been transmuted into chemistry, as the change of name reflected. Here a digression into the origins of the word ‘chemistry’ seems appropriate. There is, in fact, no scholarly consensus over the origins of the Greek word ‘chemeia’ or ‘chymia’. One familiar suggestion has been a derivation of the Coptic word ‘Khem’, meaning the black land (Egypt), and etymological transfer to the blackening processes in dyeing, metallurgy and pharmacy. What is certain is that philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle had no word for chemistry, for the term ‘chymia’, meaning to fuse or cast a metal, dates only from about 300 AD. A Chinese origin from the word ‘Kim-Iya’, meaning ‘gold-making juice’, has not been authenticated, though Needham has plausibly suggested that the root ‘chem’ may be equivalent to the Chinese ‘chin’, as in the phrase for the art of transmutation, lien chin shu. The Cantonese pronunciation of this phrase would be, roughly, lin kem shut, i.e. with a hard ‘k’ sound. Needham concludes that we have the possibility that ‘the name for the Chinese “gold art”, crystallised in the syllable chin (kiem) spread over the length and breadth of the Old World, evoking first the Greek terms for chemistry and then, indirectly, the Arabic one’.

Whatever the etymology, the Latin and English words alchemia, alchemy and chemistry were derived from the Arabic name of the art, ‘al Kimiya’ or ‘alkymia’. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, the Arabic definite article, ‘al’, was dropped in the sixteenth century when scholars began to grasp the etymology of the Latin ‘alchimista’, the chemist or practitioner; but it is far more likely to have followed Paracelsus’ decision to refer to medical chemistry as ‘chymia’ or ‘iatrochemia’. The word ‘chymia’ was also used extensively by the humanist physician, Georg Agricola (1494–1555), whose study of the German mining industry, De re metallica, was published in 1556. Although he used Latin coinages such as ‘chymista’ and ‘chymicus’, it is clear from their context that he was still referring, however, to alchemy, alchemical techniques and alchemists, and that he was, in the tradition of humanism, attempting to purify the spelling of a classical root that had been barbarized by Arabic contamination.

Agricola’s simplifications were widely adopted, notably in the Latin dictionary compiled by the Swiss naturalist, Konrad Gesner (1516–65) in 1551, as well as in his De remediis secretis: liber physicus, medicus et partim etiam chymicus (Zurich, 1552). As Rocke has shown, the latter work on pharmaceutical chemistry was widely translated into English, French and Italian, and seems to have been the fountain for the words that became the basis of modern European vocabulary: chimique, chimico, chymiste, chimist, etc. Curiously, the German translation of Gesner continued to render ‘chymistae’ as ‘Alchemisten’. German texts only moved towards the form Chemie and Chemiker in the early 1600s.

By then, influenced by the practical textbook tradition instituted by Libavius, as well as by the iatrochemistry of Paracelsus (chapter 2), ‘alchymia’ or ‘alchemy’ were increasingly terms confined to esoteric religious practices, while ‘chymia’ or ‘chemistry’ were used to label the long tradition of pharmaceutical and technological empiricism.

NEWTON’S ALCHEMY

When the economist, John Maynard Keynes, bought some of Newton’s manuscripts in 1936 when Newton’s papers were unfortunately dispersed, he drew attention to the non-mathematical, ‘irrational’ side of Newton. Here was a famous scientist who had spent an equal part of his time, if not the major part, on a chronology of the scriptures, alchemy, occult medicine and biblical prophecies. For Keynes, Newton had been the last of the magicians. Historians have tended to ignore Newton’s alchemical and religious interests, or simply denied that they had anything to do with his work in mathematics, physics and astronomy. More recently, however, historians such as Robert Westfall and Betty Jo Dobbs, who have immersed themselves in the estimated one million words of Newton’s surviving alchemical manuscripts, have seen his interest in alchemy as integral to his approach to the natural world. They view Newton as deeply influenced by the Neoplatonic and Hermetic movements of his day, which, for Newton, promised to open a window on the structure of matter and the hidden powers and energies of Nature that elsewhere he tried to express and explain in the language of corpuscles, attractions and repulsions.

For example, the German scholar, Karin Figula, has been able to demonstrate that Newton was steeped in the work of Michael Sendivogius (1556–1636?), a Polish alchemist who worked at the Court of Emperor Rudolph II at Prague, where he successfully demonstrated an apparent transmutation in 1604. In his several writings, which were translated and circulated in Britain, Sendivogius wrote of a ‘secret food of life’ that vivified all the creatures and minerals of the world7:

Man, like all other animals, dies when deprived of air, and nothing will grow in the world without the force and virtue of the air, which penetrates, alters, and attracts to itself the multiplying nutriment.

As we shall see in the following chapter, this Stoic and Neoplatonic concept of a universal animating spirit, or pneuma, which bathed the cosmos, was to stimulate some interesting experimental work on combustion and respiration in the 1670s.

In a spurious work of Paracelsus, Von den natürlichen Dingen, it had been predicted that a new Elijah would appear in Europe some sixty years after the master’s death. A new age would be ushered in, in which God would finally reveal the secrets of Nature. This prophecy may explain why, as William Newman has suggested, early seventeenth-century Europe was peopled by several adepts like Sendivogius who claimed unusual powers and insights. Another, this time fictitious, adept was ‘Eirenaeus Philalethes’, whose copious writings were closely read by Newton. It is possible that Newton developed his interest in alchemy while a student at Cambridge in the 1660s under the tutelage of Isaac Barrow, who had an alchemical library. But it is equally likely that it was Robert Boyle’s interest in alchemy and in the origins of colours that stimulated Newton’s interest, as well as making him a convinced mechanical philosopher. Like Boyle, Newton was interested in alchemical reports of transmutations as providing circumstantial evidence for the corpuscular nature of matter. In addition, however, Newton was undoubtedly interested in alchemists’ Neoplatonic claims of secret (or hidden) virtues in the air and of attractions between heavenly and earthly matter, and in the possibility, claimed by many alchemical authorities, that metals grew in the earth by the same laws of growth as vegetables and animals. In April 1669 Newton bought a furnace as well as a copy of the compilation of alchemical tracts, Theatrum Chemicum. Among his many other book purchases was the Secrets Reveal’d of the mysterious Eirenaeus Philalethes, whom we now know to have been one of Boyle’s New England acquaintances, George Starkey. The book, which Newton heavily annotated, aimed to show that alchemy mirrored God’s labours during the creation and it referred to the operations of the Stoics’ animating spirit in Nature.

Starkey laid stress upon the properties of antimony, whose ability to crystallize in the pattern of a star following the reduction of stibnite by iron had first been published by the fictitious monk, ‘Basil Valentine’ in 1604 in The Triumphant Chariot of Antimony, one of the most important alchemical treatises ever published. Valentine, who was supposed to have lived in the early fifteenth century, was the invention of Johann Tholde, a salt boiler from Thuringia. The Triumphant Chariot was concerned with the preparation of antimony elixirs to cure various ailments, including venereal disease. In Secrets Reveal’d, Starkey referred to crystalline antimony (child of Saturn from its resemblance to lead) as a magnet on account of its pattern of rays emanating from, or towards, the centre. Newton appears to have spent much of his time in the laboratory in the 1670s investigating the ‘magnetic’ properties of the star, or regulus, of antimony, probably in the shared belief with Philalethes that it was indeed a Royal Seal, that is, God’s sign or signature of its unique ability to attract the world’s celestial and vivifying spirit.

Very possibly it was Newton’s interest in solving the impossibly difficult problem of how passive, inert corpuscles organized themselves into the living entities of the three kingdoms of Nature that drove him to explore the readily available printed texts and circulating manuscripts of alchemy, including, in particular, the works of Sendivogius and Starkey. As Professor Dobbs has expressed it8: ‘it was the secret of [the] spirit of life that Newton hoped to learn from alchemy’. Newton’s motive, which was probably shared by many other seventeenth-century figures, including Boyle, was quite respectable. Its purpose, ultimately, was theological. A deeper understanding of God could well come from an understanding of the ‘spirit’, be it light, warmth, or a universal ether, which animated all things.

THE DEMISE OF ALCHEMY AND ITS LITERARY TRADITION

Historians of science are the first to stress that any theory, however erroneous in later view, is better than none. Even so, many historians of science have expressed surprise that alchemy lasted so long, though we can easily underestimate the power of humankind’s fear of death and desire for immortality – or of human cupidity. To the extent that it undoubtedly stimulated empirical research, alchemy can be said to have made a positive contribution to the development of chemistry and to the justification of applying scientific knowledge to the relief of humankind’s estate. This is different, however, from saying that alchemy led to chemistry. The language of alchemy soon developed an arcane and secretive technical vocabulary designed to conceal information from the uninitiated. To a large degree this language is incomprehensible to us today, though it is apparent that the readers of Geoffrey Chaucer’s ‘Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale’ or the audiences of Ben Jonson’s The Alchemist were able to construe it sufficiently to laugh at it.

Warnings against alchemists’ unscrupulousness, which

TABLE 1.2 Chemicals listed in Chaucer’s ‘Canon’s Yeoman’s Tale.’

Alkali Litharge Alum Oil of Tartar Argol Prepared Salt Armenian bole Quicklime Arsenic Quicksilver Ashes Ratsbane Borax Sal ammoniac Brimstone Saltpetre Bull’s gall Silver Burnt bones Urine Chalk Vitriol Clay Waters albificated Dung Waters rubificated Egg White Wort Hair Yeast Iron scales Note that alcohol is not cited. Adapted from W. A. Campbell, ‘The Goldmakers’, Proceedings of the Royal Institution, 60 (1988) 163.are found in William Langland’s Piers Plowman, were developed amusingly by Chaucer in the Chanouns Yemannes Tale (c. 1387) in which he exposed some half-dozen ‘tricks’ used to delude the unwary. These included the use of crucibles containing gold in their base camouflaged by charcoal and wax; stirring a pot with a hollow charcoal rod containing a hidden gold charge; stacking the fire with a lump of charcoal containing a gold cavity sealed by wax; and palming a piece of gold concealed in a sleeve. Deception was made the more easy from the fact that only small quantities were needed to excite and delude an investor into parting with his or her money. These methods had hardly changed when Ben Jonson wrote his satirical masterpiece, The Alchemist, in 1610, except that by then the doctrine of multiplication – the claim that gold could be grown and expanded from a seed – had proved an extremely useful way of extracting gold coins from the avaricious.

As their expert use of alchemical language shows, both Chaucer and Jonson clearly knew a good deal about alchemy, as equally clearly did their readers and audiences (see Table 1.2). Chaucer had translated the thirteenth-century French allegorical romance, Roman de la Rose, which seems to have been influenced by alchemical doctrines, while Jonson based his character, Subtle, on the Elizabethan astrologer, Simon Forman, whose diary offers an extraordinary window into the mind of an early seventeenth-century occultist.

By Jonson’s day, the adulteration and counterfeiting of metal had become illegal. As early as 1317, soon after Dante had placed all alchemists into the Inferno, the Avignon Pope John XXII had ordered alchemists to leave France for coining false money, and a few years later the Dominicans threatened excommunication to any member of the Church who was caught practising the art. Nor were the Jesuits friendly towards alchemy, though there is evidence that it was the spiritual esoteric alchemy that chiefly worried them. Athanasius Kircher (1602–80), for example, defended alchemical experiments, published recipes for chemical medicines and upheld claims for palingenesis (the revival of plants from their ashes), as well as running a ‘pharmaceutical’ laboratory at the Jesuits’ College in Rome. In 1403, the activities of ‘gold-makers’ had evidently become sufficiently serious in England for a statute to be passed forbidding the multiplication of metals. The penalty was death and the confiscation of property. Legislation must have encouraged scepticism and the portrayal of the poverty-striken alchemist as a self-deluded ass or as a knowing and crafty charlatan who eked out a desperate existence by duping the innocent.

Legislation did not, however, mean that royalty and exchequers disbelieved in aurifaction; rather, they sought to control it to their own ends. In 1456 for example, Henry VI of England set up a commission to investigate

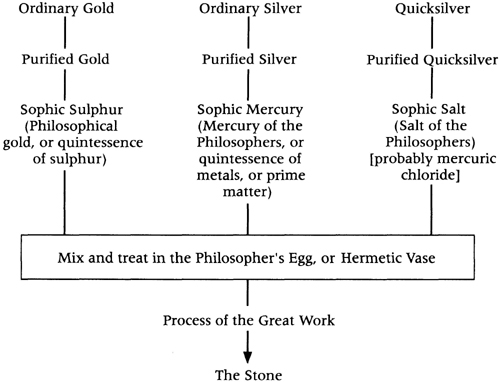

FIGURE 1.1 The preparation of the philosopher’s stone.

(After J. Read, Prelude to Chemistry; London: G. Bell, 1936, p. 132.)

the secret of the philosopher’s stone, but learned nothing useful. In Europe, Emperors and Princes regularly offered their patronage – and prisons – to self-proclaimed successful projectionists. The most famous and colourful of these patrons, who included James IV of Scotland, was Rudolf II of Bohemia, who, in his castle in Prague, surrounded himself with a large circle of artists, alchemists and occultists. Among them were the Englishmen John Dee and Edmund Kelly and the Court Physician, Michael Maier (1568–1622), whose Atalanta fugiens (1618) is noted for its curious combination of allegorical woodcuts and musical settings of verses describing the alchemical process. It was Maier, too, who translated Thomas Norton’s fascinating poem, The Ordinall of Alchemy, into Latin verse in 1618.

Such courts, like Alexandria in the second century BC, became melting pots for a growing gulf between exoteric and esoteric alchemy and the growing science of chemistry. Like Heinrich Khunrath (1560–1605), who ‘beheld in his fantasy the whole cosmos as a work of Supernal Alchemy, performed in the crucible of God’, the German shoemaker, Jacob Boehme (1575–1624), enshrined alchemical language and ideas into a theological system. By this time, too, alchemical symbolism had been further advanced by cults of the pansophists, that is by those groups who claimed that a complete understanding, or universal knowledge, could only be obtained through personal illumination. The Rosicrucian Order, founded in Germany at the beginning of the seventeenth century, soon encouraged the publication of a multitude of emblematic texts, all of which became grist to the mill of esoteric alchemy.

Given that by the sixteenth century, if not before, artisans and natural philosophers had sufficient technical knowledge to invalidate the claims of transmutationists, it may be wondered why belief survived. No doubt the divorce between the classes of educated natural philosophers and uneducated artisans (which Boyle tried to close) was partly responsible. There were also the accidents and uncertainties caused by the use of impure and heterogeneous materials that must have often seemingly ‘augmented’ working materials. As one historian has said, ‘fraudulent dexterity, false philosophy, public credulity and Royal rapacity’ all played a part. To these very human factors, however, must be added the fact that, for seventeenth-century natural philosophers, the corpuscular philosophy to which they were committed underwrote the concept of transmutation even more convincingly than the old four-element theory they rejected (chapter 2).

Nevertheless, despite the fact that the mechanical philosophy allowed, in principle, the transmutation of matter, by the mid eighteenth century it had become accepted by nearly all chemists and physicists that alchemy was a pseudo-science and that transmutation was technically impossible. Those few who claimed otherwise, such as James Price (1752–83), a Fellow of the Royal Society, who used his personal fortune in alchemical experiments, found themselves disgraced. Price committed suicide when challenged to repeat his transmutation claims before Sir Joseph Banks and other Fellows of the Society. By then, chemists had come to share Boerhaave’s disbelief in alchemy as expressed in his New Method of Chemistry (1724). Alchemy had become history, and they happily accepted Boerhaave’s allegory of the dying farmer who had told his sons that he had buried treasure in the fields surrounding their home. The sons worked so energetically that they achieved prosperity even though they failed totally to find what they had originally sought.

The absorption of the experimental findings of exoteric alchemy by chemistry left esoteric alchemy to those who continued to believe that there ‘was more to Heaven and earth’ than particles and forces. Incredible stories of transmutations continued to surface periodically during the eighteenth century. Indeed, legends concerning the ‘immortal’ adventurer, the Comte de Saint-Germain, continue into the twentieth century. In Germany, in particular, the Masonic order of Gold- und Rosenkreuz, which was patronized by King Frederick William II of Prussia, combined a mystical form of Christianity with practical work in alchemy based upon the study of collections of alchemical manuscripts. All of this increasingly ran against the rationalism and enlightenment of the age, and we know that at least one member, the naturalist, Georg Forster, left the movement a disillusioned man. Other alchemical echoes were to be heard in the speculative Naturphilosophie that swept through the German universities at the beginning of the nineteenth century and in the modified Paracelsianism of Samuel Hahnemann’s homeopathic system, which he launched in 1810.

Modern alchemical esotericism dates from 1850 when Mary Ann South, whose father had encouraged her interest in the history of religions and in mysticism, published A Suggestive Enquiry into the Hermetic Mystery. This argued that alchemical literature provided the mystic religious contemplative with a direct link to the secret knowledge of ancient mystery religions. After selling only a hundred copies of the book, father and daughter burned the remaining copies. Later, after she had married the Rev. A. T. Atwood, she claimed that the bonfire had taken place to prevent the teachings from falling into the wrong hands. Whatever one makes of this curious affair, her insight that alchemists had been really searching for spiritual enlightenment and not a material stone, supported by the translation of various alchemical texts into English, proved influential on Carl Jung when, in old age, Mrs Atwood republished her study in 1920. It also inspired Eugène Canseliet in France to devote his career to the symbolic interpretation of the statuary and frescoes of Christian churches and chateaux, as a result of the publication in 1928 of Le Mystère des Cathedrals by the mysterious adept ‘Fulcanelli’. The ability of the human mind to read anything into symbols has been mercilessly exposed by Umberto Eco in his novel, Foucault’s Pendulum (1988). In counterbalance, Patrick Harpur’s Mercurius (1990) paints a vividly sympathetic portrait of the esoteric mind.