скачать книгу бесплатно

Jardir nodded. “As you should, Drillmaster. I am Nie Ka.” Kaval grunted and left it at that.

Jardir went to the others. “Jurim, Abban, get on the carts,” he ordered. “You’re fresh from the dama’ting pavilion, and not ready for a full day’s march.”

“Camel’s piss!” Jurim snarled, pointing a finger in Jardir’s face. “I’m not riding the cart like a woman just because the pig-eater’s son can’t keep up!”

The words were barely out of Jurim’s mouth before Jardir struck. He grabbed Jurim’s wrist and twisted around to push hard against Jurim’s shoulder. The boy had no choice but to go limp lest Jardir break his arm, and the throw landed him heavily on his back. Jardir kept hold of the arm, pulling hard as he put his foot on Jurim’s throat.

“You’re riding on the cart because your Nie Ka commands it,” he said loudly as Jurim’s face reddened. “Forget that again at your peril.”

Jurim’s face was turning purple by the time he managed to nod, and he gasped air desperately when Jardir released the hold. “The dama’ting commanded that you walk farther each day until you are at full strength,” Jardir lied. “Tomorrow you march an hour longer.” He looked at Abban coldly. “Both of you.”

Abban nodded eagerly, and the two boys headed for the carts. Jardir watched them go, praying for Abban’s swift recovery. He could not save face for him forever.

He looked to the other nie’Sharum, staring at him, and snarled. “Did I call a halt?” he demanded, and the boys quickly resumed their march. Jardir called the steps at double time until they caught back up.

Night came, and Jardir had his nie’Sharum prepare the meals and lay bedrolls as the dama and Pit Warders prepared the warding circle. When the circle was ready, the warriors stood at its perimeter, facing outward with shields locked and spears at the ready as the sun set and the demons rose.

This near to the city, sand demons rose in force, hissing at the dal’Sharum and flinging themselves at the warriors. It was the first time he had seen them up close, and Jardir watched the alagai with a cold eye, memorizing their movements as they leapt to the attack.

The Pit Warders had done their work well, and magic flared to keep the demons at bay. As they struck the wards, the dal’Sharum gave a shout and thrust their spears. Most blows were turned by the sand demons’ armor, but a few precise blows to eyes or down open throats scored a kill. It seemed a game to the warriors, attempting to deliver such a pinpoint blow in the momentary flash of the magic’s light, and they laughed and congratulated the handful of warriors who managed it. Those who had went to their meal, while those who had not kept trying as the demons began to gather. Hasik was one of the first to fill his bowl, Jardir noted.

He looked to Drillmaster Kaval, coming out of the circle after killing a demon of his own. His red night veil was raised, the first time Jardir had ever seen it so. He caught the drillmaster’s eye, and when the man nodded Jardir approached, bowing deeply.

“Drillmaster,” he said, “this is not alagai’sharak as we were taught it.”

Kaval laughed. “This is not alagai’sharak at all, boy, just a game to keep our spears sharp. The Evejah commands that alagai’sharak only be fought on prepared ground. There are no demon pits here, no maze walls or ambush pockets. We would be fools to leave our circle, but that is no reason why we cannot show a few alagai the sun.”

Jardir bowed again. “Thank you, Drillmaster. I understand now.”

The game went on for hours more, until the remaining demons decided there was no gap in the wards and began to circle the camp or sat back on their haunches out of spear’s reach, watching. The warriors with full stomachs then went to take watch, hooting and catcalling at those who had failed to make a kill as they went to their meal.

After all had eaten, half the warriors went to their bedrolls, and the other half stood like statues in a ring around the camp. After a few hours’ sleep, the warriors relieved their brothers.

The next day, they passed through a khaffit village. Jardir had never seen one before, though there were many small oases in the desert, mostly to the south and east of the city, where a trickle of water sprouted from the ground and filled a small pool. Khaffit who had fled the city would often cluster at these, but so long as they fed themselves and did not beg at the city wall or prey on passing merchants, the dama were content to ignore them.

There were larger oases, as well, where a large pool meant a hundred or more khaffit might gather, often with women and children in tow. These the dama did pay some mind to, with the warrior tribes claiming individual oases as they did the wells of the city, taxing the khaffit in labor and goods for the right to live there. Dama would occasionally travel to the villages closest to the city, taking any young boys to Hannu Pash and the most beautiful girls as jiwah’Sharum for the great harems.

The village they passed through had no wall, just a series of sandstone monoliths around its perimeter with ancient wards cut deep into the stone. “What is this place?” Jardir wondered aloud as they marched.

“They call the village Sandstone,” Abban said. “Over three hundred khaffit live here. They are known as pit dogs.”

“Pit dogs?” Jardir asked.

Abban pointed to a giant pit in the ground, one of several in the village, where men and women toiled together, harvesting sandstone with shovel, pick, and saw. The folk were broad of shoulder and packed with muscle, quite unlike the khaffit Jardir knew from the city. Children worked alongside them, loading carts and leading the camels that hauled the stone up out of the pits. All wore tan clothes—man and boy alike in vest and cap, and the women and girls in tan dresses that left little to the imagination, their faces, arms, and even legs mostly uncovered.

“These are strong people,” Jardir said. “By what rule are these men khaffit? Are they all cowards? What about the girls and boys? Why are they not called to marriage or Hannu Pash?”

“Their ancestors were khaffit by their own failing, perhaps, my friend,” Abban said, “but these people are khaffit by birth.”

“I don’t understand,” Jardir said. “There are no khaffit by birth.”

Abban sighed. “You say all I think of is merchanting, but perhaps it is you who does not think of it enough. The Damaji want the stone these people harvest, and a healthy stock to do the work. In exchange, they instruct the dama not to come for the khaffit’s children.”

“Condemning the children to spending their lives as khaffit, as well,” Jardir said. “Why would their parents want that?”

“Parents can behave strangely when men come to take their children,” Abban said.

Jardir remembered his mother’s tears, and the shrieks of Abban’s mother, and could not disagree. “Still, these men would make fine warriors, and their women fine wives who breed strong sons. It is a waste to see them squandered so.”

Abban shrugged. “At least when one of them is injured, his brothers don’t turn on him like a pack of wolves.”

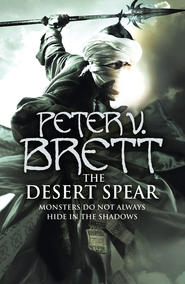

It was another six days of travel before they reached the cliff face overlooking the river that fed the village of Baha kad’Everam. They encountered no more khaffit villages along the way. Abban, whose family traded with many of the villages, said it was because an underground river fed many oases near the city, but it did not stretch so far east. Most of the villages were south of the city, between the Desert Spear and the distant southern mountains, along the path of that river. Jardir had never heard of a river underground, but he trusted his friend.

The river before them was not precisely underground, but it had eroded a deep valley over time, cutting through countless layers of sandstone and clay. They could see its bed far below, though the water seemed only a trickle from such a height.

They marched south along the cliff until the path leading down to the village came into sight, invisible until they were almost on top of it. The dal’Sharum blew horns of greeting, but there was no response as they made their way down the steep, narrow road to the village square. Even there in the center of town, there were no inhabitants to be found.

The village of Baha kad’Everam was built in tiers cut into the cliff face. A wide, uneven stair led up in zigzag, forming a terrace for the adobe buildings on each level. There were no signs of life in the village, and cloth door flaps drifted lazily in the breeze. It reminded Jardir of some of the older parts of the Desert Spear; large parts of the city were abandoned as the population dwindled. The ancient buildings were a testament to when Krasians were numberless.

“What happened here?” Jardir wondered aloud.

“Isn’t it obvious?” Abban asked. Jardir looked at him curiously.

“Stop staring at the village and take a wider look,” Abban said. Jardir turned and saw that the river had not appeared to be a trickle merely because of a trick of height. The waters hardly reached a third of the way up the deep bed.

“Not enough rain,” Abban said, “or a diversion of the water’s path upriver. The change likely robbed the Bahavans of the fish they depended on to survive.”

“That wouldn’t explain the death of a whole village,” Jardir said.

Abban shrugged. “Perhaps the water turned sour as it shallowed, picking up silt from the riverbed. Either way, by sickness or hunger, the Bahavans must not have been able to maintain their wards.” He gestured to the deep claw marks in the adobe walls of some of the buildings.

Kaval turned to Jardir. “Search the village for signs of survivors,” he said. Jardir bowed and turned to his nie’Sharum, breaking them into groups of two and sending each to a different level. The boys darted up the uneven stairs as easily as they ran the walltops of the Maze.

It quickly became apparent that Abban had been right. There were signs of demons in almost every building, claw marks on walls and furniture and signs of struggle everywhere.

“No bodies, though,” Abban noted.

“Eaten,” Jardir said, pointing to what appeared to be black stone with a few bits of white sticking from it, sitting on the floor.

“What’s that?” Abban asked.

“Demon dung,” Jardir said. “Alagai eat their victims whole and shit out the bones.” Abban slapped a hand to his mouth, but it was not enough. He ran to the side of the room to retch.

They reported their findings to Drillmaster Kaval, who nodded as if this were no surprise. “Walk at my back, Nie Ka,” he said, and Jardir followed him as the drillmaster walked over to where Dama Khevat stood with the kai’Sharum.

“The nie’Sharum confirm there are no survivors, Dama,” Kaval said. The kai’Sharum outranked him, but Kaval was a drillmaster and had likely trained every warrior on the expedition, including the kai’Sharum. As it was said, The words of the red veil carry more weight than the white.

Dama Khevat nodded. “The alagai cursed the ground when they broke through the wards, trapping the spirits of the dead khaffit in this world. I can feel their screams in the air.” He looked up at Kaval. “A Waning is upon us. We will spend the first two days and nights preparing the village and praying.”

“And on the third night of Waning?” Kaval asked.

“On the third night, we will dance alagai’sharak,” Khevat said, “to hallow the ground and set their spirits free, that they might be reincarnated in hope of a better caste.”

Kaval bowed. “Of course, Dama.” He looked up at the stairs and buildings built into the cliff face, and the wide courtyard beneath leading down to the riverbank. “It will be mostly clay demons here,” he guessed, “though likely a few wind and sand as well.” He turned to the kai’Sharum. “With your permission, I will have the dal’Sharum dig warded demon pits in the courtyard, and set ambush points on the stairs to drive the alagai off the cliff and into the pits to await the sun.”

The kai’Sharum nodded, and the drillmaster turned to Jardir. “Set the nie’Sharum to clearing the buildings of any debris we can make into barricades.” Jardir nodded and turned to go, but Kaval caught his arm. “See that they loot nothing,” he warned. “All must go as sacrifice to alagai’sharak.”

“You and I will clear the first level,” Jardir told Abban.

“Seven is a luckier number,” Abban said. “Let Jurim and Shanjat clear the first.”

Jardir looked at Abban’s leg skeptically. Abban had managed to keep up with the march, but his limp had not gone away, and Jardir often saw him massaging the limb when he thought no one was watching.

“I thought the first would be an easier ascent, with your leg not fully healed,” Jardir said.

Abban put his hands on his hips. “My friend, you wound me!” he said. “I am fit as the finest camel in the bazaar. You were right to push me to exceed myself each day, and a climb to the seventh level will only help.”

Jardir shrugged. “As you wish,” he said, and they set off climbing the steps after he had given instructions to the other nie’Sharum.

The irregular stone steps of Baha were cut into the cliff face, shored at key points with sandstone and clay. They were sometimes as narrow as a man’s foot, and other times required many paces to the next step. Worn stone showed the passage of many laden wagons pulled by beasts of burden. The steps changed direction with each tier, branching off a path to the buildings of that level.

They had not gone far before Abban’s breath labored, his round face beading with sweat. His limp grew worse, and by the fifth level he was hissing in pain with every step.

“Perhaps we’ve gone far enough for one day,” Jardir ventured.

“Nonsense, my friend,” Abban said. “I am…” he groaned and blew out a breath, “…strong as a camel.”

Jardir smiled and slapped him on the back. “We’ll make a warrior of you yet.”

They reached the seventh level at last, and Jardir turned to look out over the low wall. Far below, the dal’Sharum bent their backs, digging wide demon pits with short spades. The pits were set right at the edge of the first tier, so that a demon hurled from the very wall Jardir looked over would land within. Jardir felt a flash of excitement for the battle to come, even though he and the other nie’Sharum would not be allowed to fight.

He turned to Abban, but his friend had moved on down the terrace, ignoring the view.

“We should start clearing the buildings,” Jardir said, but Abban seemed not to hear, limping purposefully away. Jardir caught up just as Abban stopped in front of a great archway, breaking into a wide smile as he looked up at the symbols carved into the arch.

“Level seven, I knew it!” Abban said. “The same as the number of pillars between Heaven and Ala.”

“I’ve never seen wards like those,” Jardir said, looking at the symbols.

“Those aren’t wards, they are drawn words,” Abban said.

Jardir looked at him curiously. “Like those written in the Evejah?”

Abban nodded. “They read: ‘Here, seven tiers from Ala to honor He who is Everything, is the humble workshop of Master Dravazi.’ ”

“The potter you spoke of,” Jardir growled. Abban nodded, moving to push back the bright curtain that hung in the doorway, but Jardir grabbed his arm, pulling Abban to face him.

“So you can embrace pain when it comes to profit, but not to honor?” he demanded.

Abban smiled. “I am merely practical, my friend. You cannot spend honor.”

“You can in Heaven,” Jardir said.

Abban snorted. “We cannot clothe our mothers and sisters from Heaven.” He pulled his arm free and entered the shop. Jardir had no choice but to follow, walking right into Abban, who had stopped short just within the doorway, his mouth hanging open.

“The shipment is intact,” Abban whispered, his eyes taking on a covetous gleam. Jardir followed his gaze, and his own eyes widened as well. There, stacked neatly upon great pallets, was the most exquisite pottery he had ever seen. It filled the room—pots and vases and chalices, lamps and plates and bowls. All of it painted in bright color and gold leaf, fire-glazed to a pristine shine.

Abban rubbed his hands together with excitement. “Do you have any idea what this is worth, my friend?” he asked.

“It doesn’t matter,” Jardir said. “It isn’t ours.”

Abban looked at him as if he were a fool. “It isn’t stealing if the owners are dead, Ahmann.”

“It is worse than stealing, to loot from the dead,” Jardir said. “It is desecration.”

“Desecration would be casting a master artisan’s life’s work into a rubbish pile,” Abban said. “There is plenty of other debris to use in the barricades.”

Jardir considered the pottery. “Very well,” he said at last. “We will leave it here. Let it tell the story of the craft of this greatest of khaffit, that Everam may look down upon his works and reincarnate his spirit to a higher caste.”

“What need to tell tales to Everam, if He is all-knowing?” Abban asked.

Jardir balled a fist, and Abban took a step back. “I will not hear Everam blasphemed,” he growled. “Not even from you.”

Abban held his hands up in supplication. “No blasphemy intended. I merely meant Everam could see the pottery as well in a Damaji’s palace as in this forgotten workshop.”

“That may be,” Jardir conceded, “but Kaval said everything must be sacrificed to alagai’sharak, and that means this, too.”

Abban’s eyes flicked to Jardir’s fist, still tightly closed, and he nodded. “Of course, my friend,” he agreed. “But if we are truly to honor this great khaffit and recommend him to Heaven, let us use his fine pots to carry dirt for the dal’Sharum digging the demon pits. It will put the pottery to work in fighting alagai’sharak, and show Dravazi’s worth to Everam.”

Jardir relaxed, his fist falling into five loose fingers once more. He smiled at Abban and nodded. “That is a fine idea.” They selected the pieces most suited to the task and carried them back to the camp. The rest they left neatly stacked, just as they had found them.

Jardir and the others fell into their work, and the two full days and nights passed quickly as the battlefield for alagai’sharak began to form. Each night they took shelter behind their circles, studying the demons and laying their plans. The terraced tiers of the village became a maze of debris piles hiding warded alcoves the dal’Sharum would use as ambush points, leaping out to drive the alagai over the sides into the demon pits, or to net them long enough to trap them in portable circles. Supply depots were warded on every level; there the nie’Sharum would wait, ready to run fresh spears or nets to the warriors.

“Stay behind the wards until you are called for,” Kaval instructed the novices, “and when you must cross them, do so quickly, heading directly from one warded area to the next until you reach your destination. Keep ducked low behind the wall, using every bit of cover.” He made the boys memorize the makeshift maze until they could find the warded alcoves with their eyes closed, if need be. The warriors would set bonfires to see and fight by, driving off the cold of the desert night, but there would still be great pockets of shadow where the demons, which could see in the dark, would hold every advantage.

Before long Jardir and Abban were waiting in a supply depot on the third level as the sun set. The cliff wall faced east, so they watched as its shadow reached out to envelop the river valley, creeping up the far cliff wall like an inky stain. And in the shadow of the valley, the alagai began to rise.

The mist seeped from the clay and sandstone, coalescing into demonic form. Jardir and Abban watched in fascination as the demons rose in the courtyard thirty feet below, illuminated by the great bonfires as the dal’Sharum put everything flammable in Baha to the torch.

For the first time, Jardir truly understood what the dama had been telling them all these years. The alagai were abominations, hidden from Everam’s light. All of Ala would be the Creator’s paradise if not for their foul taint. He was filled with loathing to the core of his being, and knew he would give his life gladly for their destruction. He gripped one of the spare spears in the alcove, imagining the day he might hunt them with his dal’Sharum brothers.

Abban gripped Jardir’s arm, and he turned to see his friend point a shaking hand at the terrace wall just a few feet away. All along the terrace, the mists were rising, and there on the wall a wind demon was forming. It crouched, wings folded, as it solidified. Neither boy had ever been so close to a demon, and while the sight filled Abban with obvious terror, Jardir felt only rage. He gripped the spear tighter and wondered if he could charge the creature, knocking it from the wall before it was fully formed and dropping it into one of the demon pits below.

Abban squeezed Jardir’s arm so tightly it became painful. Jardir looked at his friend and saw Abban looking right into his eyes.

“Don’t be a fool,” Abban said.

Jardir looked back to the demon, but the choice was taken from him in that moment as the alagai loosed its talons from their grip on the sandstone wall and dropped away into the darkness. There was a sudden snapping sound, and the wind demon soared back upward, its huge wings blocking out the stars as it swooped by.