Полная версия:

The Desert Spear

The Desert Spear

Peter V. Brett

Copyright

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2010

Copyright © Peter V. Brett 2010

Peter V. Brett asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007276165

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2010 ISBN: 9780007301904

Version: 2018-08-13

Dedication

For Dani and Cassie

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

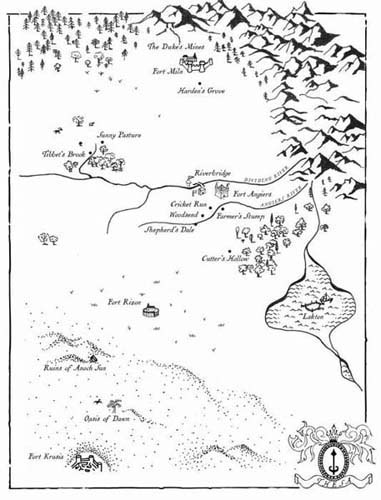

Map

Prologue Mind Demons

SECTION 1 VICTORY WITHOUT HONOR

CHAPTER 1 FORT RIZON

CHAPTER 2 ABBAN

CHAPTER 3 CHIN

CHAPTER 4 LOSING THE BIDO

CHAPTER 5 JIWAH KA

CHAPTER 6 FALSE PROPHET

CHAPTER 7 GREENLANDER

CHAPTER 8 PAR’CHIN

CHAPTER 9 SHAR’DAMA KA

CHAPTER 10 KHA’SHARUM

CHAPTER 11 ANOCH SUN

SECTION 2 OUTSIDE FORCES

CHAPTER 12 WITCHES

CHAPTER 13 RENNA

CHAPTER 14 A TRIP TO THE OUTHOUSE

CHAPTER 15 MARICK’S TALE

CHAPTER 16 ONE CUP AND ONE PLATE

CHAPTER 17 KEEPING UP WITH THE DANCE

CHAPTER 18 GUILDMASTER CHOLLS

SECTION 3 JUDGMENTS

CHAPTER 19 THE KNIFE

CHAPTER 20 RADDOCK LAWRY

CHAPTER 21 TOWN COUNCIL

CHAPTER 22 THE ROADS NOT TAKEN

CHAPTER 23 EUCHOR’S COURT

CHAPTER 24 BROTHERS IN THE NIGHT

CHAPTER 25 ANY PRICE

SECTION 4 THE CALL OF THE CORE

CHAPTER 26 RETURN TO TIBBET’S BROOK

CHAPTER 27 RUNNIN’ TO

CHAPTER 28 THE PALACE OF MIRRORS

CHAPTER 29 A PINCH OF BLACKLEAF

CHAPTER 30 FERAL

CHAPTER 31 JOYOUS BATTLE

CHAPTER 32 DEMON’S CHOICE

CHAPTER 33 A PROMISE KEPT

Keep Reading

Acknowledgments

About the Author

By the Same Author

About the Publisher

Map

Prologue Mind Demons

333 AR WINTER

IT WAS THE NIGHT before new moon, during the darkest hours when even that bare sliver had set. In a small patch of true darkness beneath the thick boughs of a cluster of trees, an evil essence seeped up from the Core.

The dark mist coalesced slowly into a pair of giant demons, their rough brown skin knobbed and gnarled like tree bark. Standing nine feet at the shoulder, their hooked claws dug at the frozen scrub and pine of the forest floor as they sniffed at the air. A low rumble sounded in their throats as black eyes scanned their surroundings.

Satisfied, they moved apart and squatted on their haunches, coiled and ready to spring. Behind them, the patch of true darkness deepened, corruption blackening the forest bed as another pair of ethereal shapes materialized.

These were slender, barely five feet tall, with soft charcoal flesh quite unlike the gnarled armor of their larger brethren. On the ends of delicate fingers and toes, their claws seemed fragile—thin and straight like a woman’s manicured nail. Their sharp teeth were short, only a single row set in a snoutless mouth.

Their heads were bloated, with huge, lidless eyes and high, conical craniums. The flesh over their skulls was knobbed and textured, pulsing around the vestigial nubs of horns.

For long moments, the two newcomers stared at each other, foreheads throbbing, as a vibration passed in the air between them.

One of the larger demons caught movement in the brush and reached out with frightening quickness to snatch a rat from its cover. The coreling brought the rodent up close, studying it curiously. As it did, the demon’s snout became ratlike, nose and whiskers twitching as it grew a pair of long incisors. The coreling’s tongue slithered out to test their sharpness.

One of the slender demons turned to regard it, forehead pulsing. With a flick of its claw, the mimic demon eviscerated the rat and cast it aside. At the command of the coreling princes, the two mimics changed shape, becoming enormous wind demons.

The mind demons hissed as they left the patch of true darkness and starlight struck them. Their breath fogged with the cold, but they gave no sign of discomfort, leaving clawed footprints in the snow. The mimics bent low, and the coreling princes walked up their wings to take perch on their backs as they leapt into the sky.

They passed over many drones as they winged north. Big and small, these all cowered until the coreling princes passed, only to follow the call left vibrating in their wake.

The mimics landed on a high rise, and the mind demons slid down to the ground, taking in the sight below. A vast army spread out on the plain, white tents dotting the land where the snow had been trampled to mud and frozen solid. Great humped beasts of burden stood hobbled in circles of power, covered in blankets against the cold. The wards around the camp were strong, and sentries, their faces wrapped in black cloth, patrolled its perimeter. Even from this distance, the mind demons could sense the power of their warded weapons.

Beyond the camp’s wards, the bodies of dozens of drones littered the field, waiting for the day star to burn them away.

Flame drones were the first to reach the rise where the princes waited. Keeping a respectful distance, they began to dance in worship, shrieking their devotion.

Another throb, and the drones quieted. The night grew deathly silent even as a great demon host gathered, drawn to the call of the coreling princes. Wood and flame drones stood side by side, their racial hatred forgotten, as wind drones circled in the sky above.

Ignoring the congregation, the mind demons kept their eyes on the plain below, their craniums pulsing. After a moment, one glanced to its mimic, imparting its desires, and the creature’s flesh melted and swelled, taking the form of a massive rock demon. Silently, the gathered drones followed it down the hill.

On the rise, the two princes and the remaining mimic waited. And watched.

When they were close to the camp, still under the cover of darkness, the mimic slowed and waved the flame drones ahead.

The smallest and weakest of corelings, flame drones glowed about the eyes and mouth from the fires within them. The sentries spotted them immediately but the drones were quick, and before the sentries could raise an alarm they were upon the wards, spitting fire.

The fire-spit fizzled where it struck the wards, but at the mind demons’ bidding, the drones focused instead on the piled snow outside the perimeter, their breath instantly turning it to scalding steam. Safe behind the wards, the sentries were unharmed, but a hot, thick fog arose, stinging their eyes and tainting the air even through their veils.

One of the sentries ran off through the camp, ringing a loud bell. As he did, the others darted fearlessly beyond the wards to skewer the nearest flame demons on their warded spears. Magic sparked as the weapons punched through their sharp, overlapping scales.

Other drones attacked from the sides, but the sentries worked in unison, their warded shields covering one another as they fought. Shouts could be heard inside the camp as other warriors rushed to join in the battle.

But under cover of fog and dark, the mimic’s host advanced. One moment the sentries’ cries were of victory, and the next they were of shock as the demons emerged from the haze.

The mimic took the first human it encountered easily, sweeping the man’s feet away with its heavy tail and snatching a flailing leg as he fell. The hapless warrior was lifted aloft by the limb, his spine cracked like a whip. Those unlucky warriors who faced the mimic next were beaten down by the body of their fallen comrade.

The other drones followed suit, with mixed success. The few sentries were quickly overwhelmed, but many drones were slow to take advantage, wasting precious time rending the dead bodies rather than preparing for the next wave of warriors.

More and more of the veiled men flowed out of the camp, falling quickly into ranks and killing with smooth, brutal efficiency. The wards on their weapons and shields flared repeatedly in the darkness.

Up on the rise, the mind demons watched the battle impassively, showing no concern for the drones falling to the enemy spears. There was a throb in the cranium of one as it sent a command to its mimic on the field.

Immediately, the mimic hurled the corpse into one of the wardposts around the camp, smashing it and creating a breach. Up on the rise, there was another throb, and the other corelings broke off from engaging the warriors and poured through the gap into the enemy camp.

Left off balance, the warriors turned back to see tents blazing as flame drones scurried about, and hear the screams of their women and children as the larger corelings broke through charred and scorched inner wards.

The warriors cried out and rushed to their loved ones, all semblance of order lost. In moments the tight, invincible units had fragmented into thousands of separate creatures, little more than prey.

It seemed as if the camp would be overrun and burned to the ground, but then a figure appeared from the central pavilion. He was clad in black, like the warriors, but his outer robe, headwrap, and veil were the purest white. At his brow was a circlet of gold, and in his hands was a great spear of shining metal. The coreling princes hissed at the sight.

There were cries at the man’s approach. The mind demons sneered at the primitive grunts and yelps that passed for communication among men, but the meaning was clear. The others were drones. This one was their mind.

Under the domination of the newcomer, the warriors remembered their castes and returned to their previous cohesion. A unit broke off to seal the outer breach. Another two fought fire. One more ushered the defenseless to safety.

Thus freed, the remainder scoured the camp, and the drones could not long stand against them. In minutes the camp was as littered with coreling bodies as the field outside. The mimic, still disguised as a rock demon, was soon the only coreling left, too quick to be taken by spear but unable to break through the wall of shields without revealing its true self.

There was a throb from the rise, and the mimic vanished into a shadow, dematerializing and seeping out of the camp through a tiny gap in the wards. The enemy was still searching for it when the mimic returned to its place by its master’s side.

The two slender corelings stood atop the rise for several minutes, silent vibrations passing between them. Then, as one, the coreling princes turned their eyes to the north, where the other human mind was said to be.

One of the mind demons turned to its mimic, kneeling back in the form of a gigantic wind demon, and walked up its extended wing. As it vanished into the night, the remaining mind demon turned back to regard the smoldering enemy camp.

CHAPTER 1 FORT RIZON

333 AR WINTER

FORT RIZON’S WALL WAS A JOKE.

Barely ten feet high and only one thick, the entire city’s defenses were less than the meanest of a Damaji’s dozen palaces. The Watchers didn’t even need their steel-shod ladders; most simply leapt to catch the lip of the tiny wall and pulled themselves up and over.

“People so weak and negligent deserve to be conquered,” Hasik said. Jardir grunted but said nothing.

The advance guard of Jardir’s elite warriors had come under cover of darkness, thousands of sandaled feet crunching the fallow, snow-covered fields surrounding the city proper. As the greenlanders cowered behind their wards, the Krasians had braved the demon-infested night to advance. Even corelings gave berth to so many Holy Warriors on the move.

They gathered before the city, but the veiled warriors did not attack immediately. Men did not attack other men in the night. When dawn’s light began to fill the sky, they lowered their veils, that their enemies might see their faces.

There were a few brief grunts as the Watchers subdued the guards in the gatehouse, and then a creak as the city gates opened wide to admit Jardir’s host. With a roar, six thousand dal’Sharum warriors poured into the city.

Before the Rizonans even knew what was happening, the Krasians were upon them, kicking in doors and dragging the men out of their beds, hurling them naked into the snow.

With its seemingly endless arable land, Fort Rizon was more populous by far than Krasia, but Rizonan men were not warriors, and they fell before Jardir’s trained ranks like grass before the scythe. Those who struggled suffered torn muscle and broken bone. Those who fought, died.

Jardir looked at all of these in sorrow. Every man crippled or killed was one who could not find glory in Sharak Ka, the Great War, but it was a necessary evil. He could not forge the men of the North into a weapon against demonkind without first tempering them as the smith’s hammer did the speartip.

Women screamed as Jardir’s men tempered them in another fashion. Another necessary evil. Sharak Ka was nigh, and the coming generation of warriors had to spring from the seeds of men, not cowards.

After some time, Jardir’s son Jayan dropped to one knee in the snow before him, his speartip red with blood. “The inner city is ours, Father,” Jayan said.

Jardir nodded. “If we control the inner city, we control the plain.”

Jayan had done well on his first command. Had this been a battle against demons, Jardir would have led the charge himself, but he would not stain the Spear of Kaji with human blood. Jayan was young to wear the white veil of captain, but he was Jardir’s firstborn, Blood of the Deliverer himself. He was strong, impervious to pain, and warrior and cleric alike stepped with reverence around him.

“Many have fled,” Asome added, appearing at his brother’s back. “They will warn the hamlets, who will flee also, escaping the cleansing of Evejan law.”

Jardir looked at him. Asome was a year younger than his brother, smaller and more slender. He was clad in a dama’s white robes without armor or weapon, but Jardir was not fooled. His second son was easily the more ambitious and dangerous of the two, and they more so than any of their dozens of younger brothers.

“They escape for now,” Jardir said, “but they leave their food stores behind and flee into the soft ice that covers the green lands in winter. The weak will die, sparing us the trouble of killing them, and my yoke will find the strong in due time. You have done well, my sons. Jayan, assign men to find buildings suitable to hold the captives before they die from cold. Separate the boys for Hannu Pash. If we can beat the Northern weakness out of them, perhaps some can rise above their fathers. The strong men we will use as fodder in battle, and the weak will be slaves. Any women of fertile age may be bred.”

Jayan struck a fist to his chest and nodded.

“Asome, signal the other dama to begin,” Jardir said, and Asome bowed.

Jardir watched his white-clad son as he strode off to obey. The clerics would spread the word of Everam to the chin, and those who did not accept it into their hearts would have it thrust down their throats.

Necessary evil.

That afternoon, Jardir paced the thick-carpeted floors of the manse he had taken as his Rizonan palace. It was a pitiful place compared with his palaces in Krasia, but after months of sleeping in tents since leaving the Desert Spear, it was a welcome touch of civilization.

In his right hand, Jardir clutched the Spear of Kaji, using it as one might a walking stick. He needed no support, of course, but the ancient weapon had brought about his rise to power, and it was never far from his grasp. The butt thumped against the carpet with each step.

“Abban is late,” Jardir said. “Even traveling with the women after dawn, he should have been here by now.”

“I will never understand why you tolerate that khaffit in your presence, Father,” Asome said. “The pig-eater should be put to death for even having raised his eyes to look upon you, and yet you take his counsel as if he were an equal in your court.”

“Kaji himself bent khaffit to the tasks that suited them,” Jardir said. “Abban knows more about the green lands than anyone, and that is knowledge a wise leader must use.”

“What is there to know?” Jayan asked. “The greenlanders are all cowards and weaklings, no better than khaffit themselves. They are not even worthy to fight as slaves and fodder.”

“Do not be so quick to claim you know all there is,” Jardir said. “Only Everam knows all things. The Evejah tells us to know our enemies, and we know very little of the North. If I am to bring them into the Great War, I must do more than just kill them, more than just dominate. I must understand them. And if all the men of the green lands are no better than khaffit, who better than a khaffit to explain their hearts to me?”

Just then, there was a knock at the door, and Abban came limping into the room. As always, the fat merchant was dressed in rich, womanly silks and fur—a garish display that he seemed to wear intentionally for the offense it gave to the austere dama and dal’Sharum.

The guards mocked and shoved him as he passed, but they knew better than to deny Abban entry. Whatever their personal feelings, hindering Abban risked Jardir’s wrath, something no man wanted.

The crippled khaffit leaned heavily on his cane as he approached Jardir’s throne, sweat pearling on his reddened, doughy face despite the cold. Jardir looked at him in disgust. It was clear he brought important news, but Abban stood panting, attempting to catch his breath, instead of sharing it.

“What is it?” Jardir snapped when his patience grew thin.

“You must do something!” Abban gasped. “They are burning the granaries!”

“What?!” Jardir demanded, leaping to his feet and grabbing Abban’s arm, squeezing so hard the khaffit cried out in pain. “Where?”

“The north ward of the city,” Abban said. “You can see the smoke from your door.”

Jardir rushed out onto the front steps, immediately spotting the rising column. He turned to Jayan. “Go,” he said. “I want the fires out, and those responsible brought before me.”

Jayan nodded and vanished into the streets, trained warriors flowing in behind him like birds in formation. Jardir turned back to Abban.

“You need that grain if you are to feed the people through the winter,” Abban said. “Every seed. Every crumb. I warned you.”

Asome shot forward, snatching Abban’s wrist and twisting his arm hard behind him. Abban screamed. “You will not address the Shar’Dama Ka in such a tone!” Asome growled.

“Enough,” Jardir said.

Abban fell to his knees the moment Asome released him, placing both hands on the steps and pressing his forehead between them. “Ten thousand pardons, Deliverer,” he said.

“I heard your coward’s counsel against advancing into the Northern cold,” Jardir said as Abban whimpered on the ground. “But I will not delay Everam’s work because of this…” he kicked at the snow on the steps, “sandstorm of ice. If we need food, we will take it from the chin in the surrounding land, who live in plenty.”

“Of course, Shar’Dama Ka,” Abban said into the floor.

“You took far too long to arrive, khaffit,” Jardir said. “I need you to find your merchant contacts among the captives.”

“If they are still alive,” Abban said. “Hundreds lie dead in the streets.”

Jardir shrugged. “Your fault for being so slow. Go, question your fellow traders and find me the leaders of these men.”

“The dama will have me killed the moment I issue a command, even if it be in your name, great Shar’Dama Ka,” Abban said.

It was true enough. Under Evejan law, any khaffit daring to command his betters was put to death on the spot, and there were many who envied Abban’s place on Jardir’s council and would be glad to see his end.

“I will send Asome with you,” Jardir said. “Not even the most fanatical cleric will challenge you then.”

Abban blanched as Asome came forward, but he nodded. “As the Shar’-Dama Ka commands.”

CHAPTER 2 ABBAN

305–308 AR

JARDIR WAS NINE WHEN the dal’Sharum took him from his mother. It was young, even in Krasia, but the Kaji tribe had lost many warriors that year and needed to bolster their ranks lest one of the other tribes attempt to encroach on their domain.

Jardir, his three younger sisters, and their mother, Kajivah, shared a single room in the Kaji adobe slum by the dry well. His father, Hoshkamin, had died in battle two years before, slain in a well raid by the Majah tribe. It was customary for one of a fallen warrior’s companions to take his widows as wives and provide for his children, but Kajivah had given birth to three daughters in a row, an ill omen that no man would bring into his household. They lived on a small stipend of food from the local dama, and if they had nothing else, they had each other.

“Ahmann asu Hoshkamin am’Jardir am’Kaji,” Drillmaster Qeran said, “you will come with us to the Kaji’sharaj to find your Hannu Pash, the path Everam wills for you.” He stood in the doorway with Drillmaster Kaval, the two warriors tall and forbidding in their black robes with the red drillmaster veils. They looked on impassively as Jardir’s mother wept and embraced him.