Полная версия:

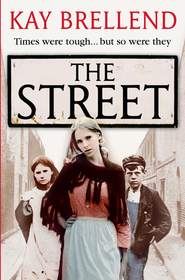

The Street

Sidney had guessed at once what had gone on. He took another look at the grizzling tart. Presently she was trying to keep her tangled blonde hair from sticking to the blood on her face. A clump of it was on the road beside her.

‘Need a hand, love?’ Sidney Bickerstaff stooped to proffer an arm.

‘Fuck off, copper,’ she replied and, clearing her throat of congealed blood and mucus, spat it onto the ground by his feet.

Twitch looked at the mess an inch from his polished shoes. ‘Lucky you missed, or you’d be licking them clean,’ he threatened softly.

‘If it ain’t yer shoes you mean it’d cost you a lot more’n you could afford, mate.’ Nellie managed a coarse laugh but it hurt, so she stopped. ‘Fuck off, copper,’ she repeated more quietly.

‘Mum! Mum, come and see, quick!’

It was a Saturday in spring and some balmy sunshine had drawn Tilly’s three oldest daughters out into the air to sit on the pavement with their cousins. Now Alice bolted upright from her squatting position on the kerb and hared into the house. She met her mother flying down the stairs when she was halfway up.

Tilly had immediately responded to her daughter’s urgent summons. ‘What the bleedin’ hell you bawlin’ out fer? What’s up?’

‘There’s a little crowd comin’ up the road! Come ‘n’ see. The man shouted at us asking if we know where he can get rooms.’ The information had streamed out of Alice, leaving her gasping for breath. It was not only the thought of a bit of entertainment to liven the humdrum routine of the day that had propelled her inside. Her mum rented out rooms for Mr Keane, so the prospect of work and money was in the offing too. Alice was very conscious of how precious was that opportunity to her family.

Mother and daughter emerged from the hallway of the tenement house into the sunshine. The sight that met Tilly’s squinting gaze caused her to blow out her lips in astonishment and mutter to herself, ‘Well, what in Gawd’s name have we got here now?’

A small, wiry man was pushing a pram, hobbling with the effort as he clearly had an injured foot. His wife, for Tilly guessed that was who the poor ragbag was, trailed behind him, holding the hands of two children. They dragged either side of her like lead weights. Behind that sorry trio slouched two bigger kids, both boys, who looked to be teenagers, carrying between them a sack. It doubtless held the family’s possessions.

As they came to a stop by her, Tilly peered into the pram. Two more children were in it, one each end, with a bag squashed between them.

‘We’ve been tramping fer days. D’you know where we can get a room or two? Cheap it’ll need to be,’ the man announced without preamble.

Tilly had been busy doing Fran’s washing. Her sister was in no fit state to lift wet sheets. Weeks had passed since Jimmy’s attack but Fran’s arms were still weak from the sprains her husband had given her. Now Tilly plonked her soap-chapped hands on her hips. Her expression betrayed her amazement. The Bunk was known to take in stragglers with nowhere else to go yet even for this depressed area of Islington this family was a very sorry sight. ‘Where’ve you lot travelled from?’

‘Essex,’ the man answered and leaned on the pram handle to ease his bad foot off the ground.

‘You walked from Essex?’ Tilly squeaked in astonishment.

The man nodded and took a glance at his listless wife. She seemed exhausted beyond speech or expression. ‘When we got to Highgate some people knew about this place and directed us here.’

For a moment longer Tilly roved a sympathetic eye over them. Then she got to business. ‘Well, you can have a couple of rooms next door. Front and back middle.’ She tipped her head to indicate the tenement house.

‘You own houses?’ the man said, fixing an interested look on her.

‘Nah!’ Tilly barked a laugh. ‘I manage ’em for me guvnor. I’ve got these two here and a few others for Mr Keane. He owns a lot of property roundabouts.’

‘How much?’ He automatically rocked the pram up and down as one of the babies let out a piercing wail.

‘Can let you have it fer a shillin’ a night. Or five shillin’ a week paid up front, however you want to do it.’

‘Ain’t got five shillin’ but that’s the way I want to do it.’

Tilly fixed her canny gaze on him. ‘Well now, might be able to help you on that score ‘n’ all. I can let you have somethin’ to pawn at a cheap rate so that’s all right.’

The man stared at his brood of silent children huddled about his wife. ‘Any work hereabouts?’ A pessimistic look met his question and made his mouth droop.

‘Some . . . but nothing much good,’ Tilly told him straight. ‘Looks like you’ll need a tidy bit more’n what half-profits down the market pays to keep this lot.’ Tilly cocked her head to look at the woman. An idea came to mind. ‘Your wife after work?’

‘’Course,’ the man roundly answered for his silent spouse.

His wife sent him a sullen stare from beneath low lids.

‘What’s your names, then?’ Tilly asked whilst giving Bethany a cuff, as she’d started to whine for a penny for the shop. ‘Get off up the road a while,’ Tilly snapped at her daughters. ‘I’m doing business here.’

The two older girls, who had been interestedly watching and listening to the exchange, each took one of Bethany’s hands and began swinging her between them as they strolled off up the street.

‘What’s yer name again?’ Tilly raised her voice to make herself heard over the screaming child in the pram.

In exasperation the fellow snatched up the fractious infant then introduced himself. ‘Bert Lovat is me name and this here’s me wife, Margaret. Be obliged if you’d show me these rooms. Won’t go through all the kids’ names. If we stay here long enough you’ll come to know ’em, I expect.’

‘I’m Tilly Keiver. I live here with me husband Jack ‘n’ our girls.’ She flicked her head to indicate the house next door. ‘Wait here and I’ll just nip indoors to fetch the key.’

Within a few minutes they were climbing up a dilapidated staircase in silence. By the time they reached the first-floor landing Bert could no longer conceal his dejection.

Despite the bright and sunny day the interior was so dismal it was hard to discern where doors were set in the drab-coloured walls. A stained sink was set against a wall on the landing and for a few moments the only sounds were a dripping tap and Tilly’s efforts to turn a key in an awkward lock.

‘What a shit hole,’ Bert bluntly commented as he and his wife drearily looked around.

‘Yeah,’ Tilly agreed over a shoulder. ‘But beggars can’t be choosers, right?’

‘Yeah . . . I ain’t choosy,’ Bert sourly agreed.

Tilly led the way into the room’s grimy interior. A few sticks of ancient, battered furniture were pushed against the walls. A fiddle-backed chair that once might have belonged to a nice set now had stuffing leaking from a corner. A wardrobe that had only one door of its pair remaining had been shoved aside to allow an iron bedstead to dominate the centre space. Beneath its springs, resting on bare boards, was an additional flock mattress. A square table with a dirty, fissured top took up the rest of the wall space.

‘Let’s see the other,’ Bert muttered in a resigned tone.

They trooped in single file into the back room. Again the man’s eyes pounced at once on the sleeping quarters: a double bed with a smaller mattress pushed underneath. ‘Big enough for the four old’uns, I suppose.’ He came back into the front room and looked at the hob grate powdered with grey ash. ‘Where’s the water?’ He swung his eyes to and fro.

‘Didn’t you see the sink on the landing? You’ve got to share with other people.’ Tilly could tell he was bitterly disappointed at the accommodation. ‘That’s why it’s cheap,’ she said with a sympathetic grimace. ‘Got another of Mr Keane’s houses up the better end o’ the road. But that’d cost more. Got a ground floor front and back. It’s a bit bigger and better furniture and a few sheets ‘n’ blankets to go with it. I could do that at seven bob fer the week . . .’

‘Nah!’ Bert harshly interrupted, shaking his head and slipping a sideways glance to his wife, for she had sunk to sit on the bed edge. ‘This’ll do. It’ll have to do.’ He shifted the baby in his arms, still rocking it to and fro although it had quietened.

‘One thing I won’t do is get meself in trouble with me guvnor,’ Tilly said firmly. ‘I collect his rent and I ain’t losing me job. So you’ve gotta pay me what’s due when it’s due or it’s trouble for everyone. That clear?’

Bert nodded and cast a wary eye at the war-like woman confronting him. He reckoned she looked like that Boadicea in a chariot who’d fought the Romans. He remembered his oldest, Danny, had brought home a book when he’d been learning about history at school. Tilly had leaned forward slightly, fists on hips, whilst awaiting his agreement. ‘Bring the stuff up,’ Bert ordered one of his sons who’d been hovering by the open door. The youth stared sulkily at his father before turning about and doing as he was told.

Bert put the baby down on the bed next to Margaret. ‘I’m off to try ‘n’ find some work,’ he said bluntly. ‘I’ll take a job clearin’ pots in a pub if it comes to it.’

‘That’s what it always comes to,’ his wife muttered acidly at his back as he limped out of the room.

‘You want any work, duck?’ Tilly settled herself on the bed next to Margaret Lovat. ‘Might be able to help, y’know.’

‘What’s goin’?’ The woman raised her eyes and pushed a stand of lank brown hair behind her ears.

‘Might be able to find you something this afternoon if you like. It’s graft but better’n nothing if you need a few bob urgent.’

‘Washing?’ the woman guessed with a dead-eyed look.

Tilly nodded. ‘Me sister Fran’s work but she ain’t fit and her client wants this back by seven tonight. Well-to-do lady she is, out Tufnell Park. Might lead somewhere.’

Margaret Lovat turned a jaundiced eye on Tilly. ‘You reckon I’m daft enough to believe I’ve got a chance of taking yer sister’s best touch?’

Tilly crossed her arms and gave Margaret a keener appraisal. So she wasn’t the mouse she’d seemed. She’d come back with that quick enough. ‘Take it or leave it.’ Tilly stood up. ‘No skin off my nose either way. Ain’t my client.’

‘I’ll do it.’

‘Come next door when yer ready. I’ll show you what’s gotta be done.’

Margaret Lovat followed her to the door. ‘Where’s the privy?’

‘Out back. Go down the stairs and do a left till you come to a door; that’ll take you out to the courtyard.’ She made to go then hesitated and said with a hint of apology, ‘I’ll prepare you fer the state of it. It’s full of Mr Brown. I’ve been on at Mr Keane fer weeks to get a plumber to fix it.’ She nodded to the landing. ‘There’s the sink. Shared with a couple called Johnson. You won’t have no trouble off them. He’s got reg’lar work on the dust and she hardly comes out the room. Got bad arthritis,’ she added by way of explanation. ‘Back slip room’s just been took by a single lady. Don’t see nuthin’ of her. Think she’s a waitress up west and that’s why she comes in all hours of the night.’ Tilly raised her eyebrows at Margaret in a way that fully exhibited her suspicions.

‘How nice,’ Margaret sighed with weary sarcasm. ‘Stuck between a totter and a prossy.’

‘She’s a looker too, is Miss Kerr, so keep an eye on yer old man.’ Tilly issued the warning with a grin.

‘Ain’t worried about him!’ Margaret snorted derisively. ‘She’s welcome to him. Give me a break at least.’

‘Yeah . . . I noticed he don’t hang about,’ Tilly said, amused. ‘Not much of a gap between your two youngest, I’d say.’

‘Thirteen months,’ Margaret sighed. ‘Little Lizzie’s just three months. I’m bleedin’ knackered, I can tell yer.’

The two women exchanged a look of cautious camaraderie.

‘It’s me eldest, Danny, I’m thinkin’ of. He’s fifteen next birthday ‘n’ comin’ of age, alright. The boy’s always got his hand stuck down the front of his trousers.’

Tilly cackled a laugh. ‘I noticed he’s a strapping lad.’

‘He is,’ Margaret said, her face softening with pride. ‘Nothing like his old man. Takes after my side. Me dad was six foot and built like a brick shit house. Danny’s bright too and was doing well in school till . . .’ She shrugged and turned away.

‘All gone sour for yers in Essex?’

‘Yeah . . . won’t be going back there no more.’

Tilly looked at Margaret’s averted face and felt sorry for the woman. Obviously there was a tale of woe to be told. But then everyone in Campbell Road had one of those. Tilly felt sorry for every poor sod that turned up in The Bunk looking for somewhere cheap to stay and a job of sorts to keep the kids fed. Sympathy was of no bloody use when what was needed was hard cash and a bit of luck for a change.

‘Yeah . . . well . . . anythin’ else you need to know, I’m just next door.’ She wiped her hands on her pinafore. ‘See yer downstairs in a bit, alright?’

Chapter Four

‘Gonna let me in, then?’ Tilly asked impatiently as her sister simply gazed at her. She’d come to tell Fran she’d found someone to take on her washing.

Slowly Fran stood aside and Tilly swept in. Fran’s bruises had almost disappeared, but a sallow colouring around her eyes and jaw was a reminder of the beating she’d taken. Her arms were healing more slowly and the muscles were still stiff and sore from being brutally treated.

‘What you looking so shifty about?’ Tilly asked bluntly.

Fran simply shrugged.

‘A new family’s moving in next door. They’ve not got a pot ter piss in. The woman wants work urgent so she’s doing your washing. We’ll get it finished and back to Tufnell in plenty of time.’

Fran gave a weak smile and muttered her thanks.

Tilly sensed something was not right and then her nose told her what it was. ‘He’s been in ’ere, ain’t he?’ she accused, taking another sniff. ‘I can smell bacca.’

‘Don’t go mad, Til,’ Fran started to wheedle but was soon interrupted.

‘Yeah, don’t go mad, Til,’ Jimmy Wild echoed, emerging from the back slip room where he’d been hiding himself. He walked closer and slung an arm about his wife’s frail shoulders. ‘We’ve made up, ain’t we, gel? I’m back home where I should be with me family.’

‘He’s said he’s sorry and he won’t do it no more. The kids need their dad.’ Fran was unable to meet Tilly’s eyes and stared at the floor.

‘You fuckin’ idiot,’ Tilly exploded. ‘How many times have you heard him say sorry ‘n’ it won’t happen again?’

Fran narrowed her eyes on her sister. ‘I can’t manage on me own. I got kids and debts.’

‘Yeah, ‘n’ he’s gonna add to them for you,’ Tilly said on a harsh laugh. ‘Just like before.’

She gave her brother-in-law a hate-filled look. He winked back, making her fight down her need to pounce on him and punch the smirk from his face.

Jack Keiver was just at that moment on his way up the stairs. Seeing the door open to his sister-in-law’s room he poked his head in to say hello. The greeting died on his lips. The scene in front of him made him hasten further into the room. He drew Tilly’s arm through his in an act of restraint and solidarity. He’d immediately guessed what had gone on. His brother-in-law had managed to squirm his way back home with lies and promises.

‘Come on, Til, leave it. We’ve been through all this before. Let ’em stew. It’s their business.’

For a moment Tilly stood undecided before allowing her husband to lead her to the door. Jack was right, but still she felt betrayed and angered by her sister’s weakness. She felt now more inclined to shake her than punch him.

Jack turned and looked at Jimmy. He raised a threatening finger. ‘We ain’t finished. I ain’t forgot you tried to take a swing at my missus. And all on account of some poxy brass.’

‘I was wrong.’ Jimmy gestured an apology with his flat palms. ‘I swear on the Holy Bible it won’t happen no more. All in the past, mate. I’m back and it’s gonna be alright this time.’

‘Yeah, ’course it is,’ Jack muttered sarcastically as he led Tilly out.

‘What d’you think of that Danny?’ Sophy asked Alice as they made their meandering way back home from the shop. They’d bought a penn’orth of liquorice and sucked on it while talking. Bethany put up a hand and Sophy obligingly wound a black string onto her palm. Their young sister then skipped happily in front of them, head back and the liquorice dangling between her lips.

‘Who?’ Alice asked with a frown.

Sophy tutted and her eyes soared skyward. ‘The new family what turned up yesterday. The biggest boy’s name’s Danny. He kept lookin’ at me. I think he fancies me.’

‘You think all the boys fancy you,’ Alice chortled.

‘Look!’ Sophy hissed and nudged Alice in the ribs. ‘Here he comes now with his brother! I bet they’ve been following us.’

Alice gave her elder sister a look. Sophy’s cheeks were turning pink and she was scraping her fingers through her brown hair to tidy it. In Alice’s estimation the new boys were probably just off to the shop. She decided not to dampen Sophy’s excitement with that opinion.

The Lovat boys made to walk past without a word and with barely a sullen look slanting from beneath their dark brows at the Keiver girls. Alice sensed her sister’s disappointment at their indifference and bit her lip to suppress a smile.

Alice’s mild amusement stoked Sophy’s indignation. She swung herself into the boys’ path and adopted a belligerent stance she’d seen her mum use, with hands plonked on her thin hips and chin jutting forward. ‘Why’ve you come all this way from Essex? You lot in trouble?’

‘What’s it ter you?’ the boy called Danny snarled and aggressively looked her up and down.

‘We don’t want no scumbags living next door,’ Sophy told him, her lip curling ferociously.

‘Nah . . . by all accounts you’ve got ‘’em livin’ in the same house,’ Danny let fly back, making his brother Geoff guffaw.

Sophy turned crimson. She’d not meant to start a proper argument with him. All she’d wanted was for him to stop and say a few words, but now she’d started this ruckus she couldn’t back down. ‘You wanna watch what you’re saying. Me dad’ll have you.’

‘Yeah . . . and I’ll have him back,’ Danny said. ‘We ain’t scared of nobody, you remember it.’

Alice, who had up till now been watching and listening, decided to give her sister some support. ‘You ain’t scared ’cos you ain’t been here long enough,’ she piped up. ‘Wait till you meet the other boys; they’ll beat you both up, you give ’em lip.’

‘Yeah.’ Sophy nodded. ‘Wait till you meet a few of ’em. Robertson brothers wot live across the road’ll thrash you good ‘n’ proper. Let’s see how big yer mouth is then.’

Danny hooted and began to act palsied. ‘Look! I’m shakin’ in me boots.’

‘You will be!’ Sophy answered but she was already edging away, aware that no gains were to be made.

The Lovat boys began to shift too. One last challenging stare over their shoulders and they were carrying on towards the shop.

Sophy stared boldly after them. ‘Knew I wouldn’t like ’em soon as I saw ’em,’ she announced loud enough for them to hear.

‘Don’t think they’re bothered whether we like ’em or not,’ Alice muttered. ‘Don’t think they like us either.’

‘Good!’ Sophy flounced about. Grabbing Bethany’s hand she yanked on it and they headed off home.

They were close to the junction with Paddington Street when Alice spotted Sarah Whitton outside her house with one of her older sisters. Louisa Whitton looked to be in a fine temper and Sarah was scooting backwards away from her, obviously to escape a whack. Louisa was a hefty, sweaty girl of about eighteen, not too bright and known to use brawn rather than brain. All of a sudden she lunged at Sarah and swiped her across the face, making her young sister howl and rub frantically at a scarlet cheek.

‘Wonder what’s goin’ on?’ Sophy murmured to Alice. Her features had transformed from moodiness, brought on by the confrontation with the Lovats, to anticipation. Family fights in the street were a common occurrence in Campbell Road and provided a bit of light relief for people living with the monotony of poverty.

‘Come on, let’s go ‘n’ see,’ Sophy urged. They started to walk faster, Bethany lagging behind. As they got closer they could hear Louisa’s raucous accusations as she stalked her sister with her fists at the ready.

‘Thievin’ li’l bitch! Give it me back or I’ll lay you out, right here ‘‘n’ now.’

‘Ain’t got it . . . ain’t got it, I tell yer. Let me go in . . . Mum’ll tell you, I ain’t got no money.’

‘What’s up?’ Alice called and ran closer to her friend. She liked Sarah and felt concerned on her behalf. She also wanted to help if she could. A worm of guilt was already squirming unpleasantly in her belly as an idea of what might be wrong entered her mind.

‘Keep yer nose out,’ Louisa bawled at her and wagged a threatening finger. She came close enough for it to land and shove against Alice’s nose. ‘You Keivers need ter mind yer own.’

‘You don’t want to let me mum hear you say that,’ Sophy piped up then piped down as Louisa shot her a pugnacious look.

‘Give me the money you got fer it, you li’l cow.’ Louisa advanced again on her snivelling sister.

‘What’s she on about?’ Alice demanded of her friend as Sarah cuffed snot from her top lip.

‘She reckons I took her new blouse down the secondhand shop in the Land. I never did, I swear.’

‘You lyin’ mare. If you didn’t who did, then? ’Cos I just been down Queensland Road ‘n’ saw it in the winder and that’s where I just got it from. Solly said he remembers a girl about your age took it in. Cost me two ‘n’ six to buy back me own soddin’ blouse. And he wanted more for it!’

Alice suddenly went very pale and very quiet. She looked at Sophy to see that her sister seemed to be engrossed in this spectacle. So were various other people who had lazily propped themselves against doorjambs or railings to watch what was going on.

‘Go on . . . give her another dig,’ one of the boys from Sophy’s class at school called out mischievously.

‘I’ll give you a dig you don’t shut up, Herbert Banks,’ Alice yelled angrily at him.

‘One more chance then I’m gonna really set about yer,’ Louisa warned.

‘Mum!’ Sarah wailed in anguish. But everyone, even Sarah, knew that help from that quarter was very unlikely. Ginny Whitton’s nerves kept her prostrate on her bed for hours on end with just a bottle of gin for company. At this time of the afternoon it was unlikely she could hear much at all through her booze-induced meditation.

‘I’ll get your two ‘n’ six,’ Alice blurted and rushed forward to step between the two sisters.

‘What’s it to you?’ Louisa dropped her hand and stared at Alice.

‘Nuthin’ . . . she’s me friend. I’ll get your money. Just leave her alone.’ Alice felt one of her sister’s hands gripping her elbow and Sophy tried to yank her away.

‘You ain’t got half a crown,’ Sophy hissed. ‘Now she’s gonna lamp you instead, stupid.’

‘Shut up,’ Alice muttered and, shaking off her sister’s fingers, she turned and sprinted for home.

‘None of our business.’ Tilly cut Alice short as her daughter neared the end of her breathless tale of woe.

‘But it is, Mum. Sarah’s gonna get a hiding and it was me took that blouse in to Solly’s place for you and we only got one and six for it.’

‘Yeah, and it was Ginny Whitton give it to me in the first place to sell for her. If Louisa’s got a beef it’s with her mother, not with us.’

‘Will you come and tell her that? She’s waiting for half a crown.’

Tilly transferred baby Lucy from one hip to the other and sipped from a cup of lukewarm tea. She was drinking it in the hope it might take the whiff of whiskey from her breath before Jack got home. ‘I got things to do,’ she answered irritably. ‘Besides, I got enough o’ me own wars to sort out without gettin’ involved in the Whittons’ dingdongs.’ Inwardly Tilly was still brooding on her sister’s monstrous stupidity in letting Jimmy come back.